FIGURE 32-1 A: Radiographs of an elbow dislocation with lateral bony fragments. B: Closed reduction radiographs in splint. Note on the lateral view that the joint is not anatomic.

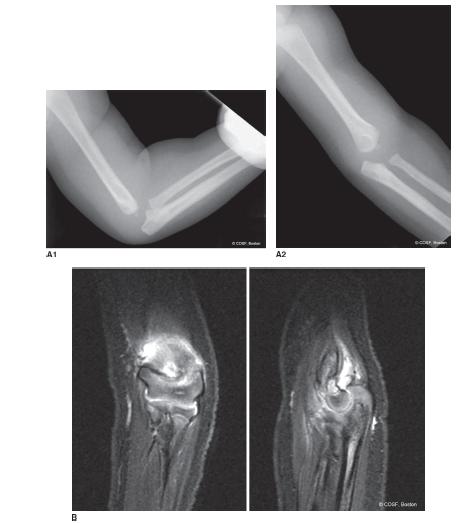

The specific injuries include (1) transphyseal fractures before capitellar ossification (Figure 32-3) (see Chapter 27); (2) anterior compression fractures of the cartilaginous radial head that lead to posterior radial head subluxation (Figure 32-4); (3) displaced medial condylar fractures before the secondary center of ossification appears (Figure 32-4) (see Chapter 29); (4) plastic deformation Monteggia lesions (see Chapter 30); (5) intra-articular osteochondral elbow fractures (olecranon, radial head, capitellum, trochlea); (6) entrapped medial epicondylar fractures4–6 (Figure 32-5) (see Chapter 29); (7) lateral condylar and epicondylar osteochondral avulsions that represent an unstable lateral collateral ligamentous injury (Figure 32-6); (8) complex osteochondral fracture dislocations with multiple intra-articular fractures; and (9) an elbow dislocation at <10 years of age should make you nervous for multiple sites of injury not always readily apparent on plain radiographs.

Further radiographic evaluation is warranted with these rare injuries.7,8 You have to know that danger is lurking around the corner. Your referring team of pediatricians, emergency room caregivers, radiologists, and trainees need to be aware of the possibility of missing something important on plain radiographs of the elbow in a young child. Oblique views of the affected elbow and comparison views of the contralateral elbow might be helpful in proper diagnosis or even just increasing your suspicions that something is not right. Ultrasounds have been shown to be helpful with skilled hands (technical part) and eyes (interpretive part). For some clinicians, ultrasounds are mere confusion, and for others, they bring clarity. If you look at a lot of hip ultrasounds for dysplasia, the elbow ultrasound will make more sense to you. The use of MRI scans is extremely helpful for most surgeons, as the MRI images match the anatomy we are used to seeing and on which we base our decisions. Arthrograms are also helpful and used most often in the operating room as a part of both diagnosis and treatment (see Chapter 28, Sidebar). Very good clinicians have missed a TRASH injury and regretted it. Obtaining one or more of these additional radiographic studies acutely, or as a part of an evaluation of a chronic condition, is important for prompt, precise treatment. You need to know exactly what the problem is before you can make the right decisions on fixing it.

SIDEBAR

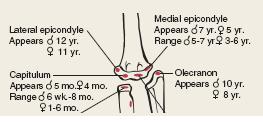

Secondary Centers of Ossification about the Elbow

In assessing traumatic injuries about the elbow, it is imperative to know the normal pattern and radiographic appearance of the secondary centers of ossification (Figure 32-2). The capitellum appears first, at 2 months to 2 years. The early appearance of the capitellum secondary center of ossification is why it is used as an indicator of fracture displacement and acceptable reduction alignment (Baumann angle, anterior humeral line, radiocapitellar line, for example). Before the appearance of the capitellum secondary ossification center, elbow bone and joint alignment can only be inferred radiographically or evaluated by ultrasounds, MRI scans, and arthrograms. The radial head appears next at 3 to 6 years of age. The medial epicondyle follows in ossification, at 3 to 7 years of age. The trochlea is next at 7 to 10 years of age, followed by the olecranon apophysis at 10 years of age and the lateral epicondyle at 12 years of age. Thus, we have the mnemonic “CRMTOL” for memorizing the sequence. Girls usually mature skeletally before boys. There are enough vagaries of the secondary ossification centers in terms of timing and appearance (especially the trochlea and olecranon) that clear understanding of the norms is essential to not mistake normal for trauma or, more importantly, assume a traumatic osteochondral lesion is “normal.”

FIGURE 32-2 Secondary centers of ossification sequence of appearance by age and gender (CRMTOL). (From Beaty JH, Kasser JR. Rockwood & Wilkins Fractures in Children. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010.)

Surgical Indications

The way to get started is to quit talking and begin doing.

—Walt Disney

Whenever the elbow joint is malaligned, anatomic reduction is required. Small osteochondral pieces that block anatomic articular reduction need to be either excised or stabilized back in place. Suture repair of articular flaps or pin or intraosseous screw (absorbable or metallic) open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) of osteochondral articular fractures is indicated and preferred if anatomic alignment and stability are to be restored. Larger intra-articular fragments, such as displaced, unossified medial condylar fractures, require arthrographically assisted, closed reduction percutaneous pinning (CRPP) or ORIF depending on the situation. Entrapped fracture fragments, such as a medial epicondyle with an elbow fracture dislocation, require extraction, anatomic reduction, and stabilization. Unstable osteochondral ligamentous injuries require protection until healed or open repair depending on the situation. Plastic deformation fractures with joint subluxation, such as a Monteggia lesion, necessitate stable fracture and joint reduction. Complex fracture dislocations may require CRPP and/or ORIF of multiple fractures in order to achieve anatomic reduction and joint stability with motion.3 All in all, aggressive surgery is indicated in TRASH lesions. Treatment of acute Monteggia fractures, medial condylar, lateral condylar, radial neck, and olecranon fractures are covered in their respective chapters.

The most difficult cases are the late-presenting intraarticular fracture malunions (see Chapter 28), missed joint subluxations, and displaced osteochondral fractures.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Radiographic Interpretation

Radiographic Interpretation

Obstacles are those frightful things you see when you take your eyes off the goal.

—Henry Ford

The theoretically simplest part, reading the radiographs properly and ordering additional images and studies, can be the hardest part. Familiarity with normal patterns and vagaries of the appearance of the secondary centers of ossification about the elbow is critical to an accurate diagnosis of each injury radiographic image in the young child (see Sidebar). We have our midlevel providers, medical students, residents, and fellows cover the patient identification information and predict the age of the child on each elbow radiograph based on the secondary centers of ossification present. We want them, and of course ourselves, to be so familiar with elbow images in the young that there is minimal chance of missing a TRASH lesion.

Lateral Collateral Ligament Osteochondral Nonunion

Lateral Collateral Ligament Osteochondral Nonunion

There are some unstable, osteochondral, lateral collateral ligament elbow injuries that are misdiagnosed either as a normal lateral epicondyle secondary center of ossification or a stable bony avulsion injury that will heal without significant intervention. Acutely these patients will be unstable to varus stress. There can be associated ligamentous and bony injuries about the elbow. An unstable nonunion can develop if the unstable osteochondral ligamentous injury is not (1) protected until healed or (2) treated with percutaneous fixation or open repair. Physical exam, stress radiographs, and MRI scans will distinguish these injuries from normal or more benign injuries. Later, these patients present with recurrent, activity-based pain and instability. The elbow will be unstable to varus stress, which will reproduce the pain. An MRI scan will indicate the articular alignment size and vascularity of the fracture fragment and status of the lateral collateral ligamentous complex. Stable fixation and repair are required to resolve their problem.

FIGURE 32-3 A: A 15-month-old infant presenting with marked elbow swelling, limited range of motion, and pain. Plain radiographs reveal soft tissue swelling and suggest extension and valgus malalignment. B: MRI confirms suspicions of transphyseal fracture. Orthopaedic treatment was CRPP with arthrogram. Medical treatment included pediatric and social service consults to evaluate for nonaccidental trauma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree