Ectopic Pregnancy

|

Ectopic pregnancy remains an important cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. However, because modern diagnostic methods now permit early recognition of most ectopic pregnancies, contemporary treatments are more conservative than in the past. The focus of attention has shifted from emergency surgery for the control of life-threatening hemorrhage to medical treatments aimed at avoiding surgery and preserving reproductive anatomy and fertility. This chapter will review the history, epidemiology, and pathogenesis of ectopic pregnancy and discuss current methods for diagnosis and treatment.

History of Ectopic Pregnancy

The modern management of ectopic pregnancy is arguably one of medicine’s greatest success stories. Ectopic pregnancy was first described in the 11th century and, for centuries thereafter, often was a fatal complication of pregnancy. In medieval times, ectopic implantation was viewed as the consequence of violent emotion, usually fright or surprise, during coitus in the cycle of conception.1 The first documented unruptured ectopic pregnancy was described in the results of an autopsy performed on a female prisoner condemned to death and executed in 1693. Ectopic pregnancy and infertility were first linked in 1752, in the report of an extrauterine pregnancy in an infertile prostitute. By the mid 19th century, autopsy observations had raised suspicion that ectopic pregnancy might be related to pelvic infection, but treatment was not yet available for either.

Early treatments were designed to kill the ectopic conceptus and included starvation, purging, bleeding, and even treatment with strychnine. Attempts to surgically disrupt or to pass electrical current into an ectopic gestational sac frequently resulted in sepsis and death. Isolated reports of abdominal surgical procedures in women with ectopic pregnancies first appeared in the early 17th century, but not again until more than 100 years later. The first known surgical procedure for ectopic pregnancy in the 18th century was performed in France, in 1714. In the United States, John Bard of New York (1759) and William Baynham of Virginia (1791) were the first to perform abdominal surgery for ectopic pregnancy.1 However, during the first 80 years of the 18th century, only 5 of 30 women who underwent abdominal surgery for ectopic pregnancy survived; those not treated had a greater chance for survival (1 in 3)!

In 1849, W.W. Harbert of Kentucky was the first to suggest early surgical intervention to stop fatal hemorrhage.2 Unfortunately, the diagnosis of ruptured ectopic pregnancy came too late for most. In 1876, John Parry of Philadelphia aptly described the prognosis for women with ectopic pregnancy in his era.3

…when one is called to a case of this kind, it is his duty to look upon his unhappy patient as inevitably doomed to die, unless he can by some active measure wrest her from the grave already yawning before her.

After witnessing the death and autopsy of several women with ectopic pregnancies, Robert Lawson Tait of London discovered the source and means to control hemorrhage in women with ruptured ectopic pregnancies and performed the first deliberate laparotomy to ligate bleeding vessels in 1884.4 Within little more than a year, Tait accumulated a relatively large and successful experience with the procedure.

Over subsequent years, the advent of aseptic techniques, anesthesia, antibiotics, and blood transfusions combined to save the lives of many women, but late diagnosis and intervention were still common. Even during the first half of the 20th century, the maternal mortality from ectopic pregnancy in the United States was between 2% and 4%. Although immediate salpingectomy and blood transfusion dramatically improved outcomes in women with ectopic pregnancy, the impact of modern methods for diagnosis and treatment developed over the last 25 years has been far greater. As recently as the 1970s, approximately 15% of women with ectopic pregnancies presented in hypovolemic shock, but by the early 1980s, fewer than 5%. Accordingly, attention shifted from saving lives to preserving fertility.

Epidemiology of Ectopic Pregnancy

The incidence of ectopic pregnancy is approximately 1.5-2% of all pregnancies. The incidence increased dramatically, by about 6-fold, between 1970 and 1992. At the same time, the risk of death related to ectopic pregnancy decreased by almost 90% (from 35.5 to 3.8 deaths/10,000 ectopic pregnancies).5 In 1989, less than 2% of all pregnancies were ectopic, but related complications accounted for 4-10% of all pregnancy-related deaths, and were the leading cause of maternal death during the first trimester.5,6 Recognizing the increasing trend towards outpatient surgical and medical management of ectopic pregnancy,7,8 and 9 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention combined data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and estimated the incidence of ectopic pregnancy at 19.7/1,000 reported pregnancies in 1992,6 the last time that U.S. national data were reported.

Efforts to determine accurately more recent trends in the incidence of ectopic pregnancy have proven very difficult, because the numbers of ectopic pregnancies managed in the

outpatient setting (not captured in hospital discharge surveys) and involving multiple health care visits (confounding data from ambulatory care surveys) have increased dramatically.10 Moreover, the incidence of ectopic pregnancy is expressed as the number of ectopic pregnancies per 1,000 pregnancies, but pregnancies not resulting in delivery or hospitalization are not counted and the large majority of failed pregnancies now are managed entirely in the outpatient setting. Nonetheless, available evidence suggests strongly that the incidence of ectopic pregnancy is now relatively stable and no longer increasing.11,12 and 13 Whereas the use of ovulation inducing drugs and assisted reproductive technologies (ART) has increased significantly in recent years (both known risk factors for ectopic pregnancy) and contemporary methods permit more accurate and earlier diagnosis than in the past (resulting in fewer ectopic pregnancies escaping detection), advances in detection and treatment of sexuallytransmitted infections have, at the same time, helped to prevent or limit related damage to the fallopian tubes (a major risk factor for ectopic pregnancy).12,14,15

outpatient setting (not captured in hospital discharge surveys) and involving multiple health care visits (confounding data from ambulatory care surveys) have increased dramatically.10 Moreover, the incidence of ectopic pregnancy is expressed as the number of ectopic pregnancies per 1,000 pregnancies, but pregnancies not resulting in delivery or hospitalization are not counted and the large majority of failed pregnancies now are managed entirely in the outpatient setting. Nonetheless, available evidence suggests strongly that the incidence of ectopic pregnancy is now relatively stable and no longer increasing.11,12 and 13 Whereas the use of ovulation inducing drugs and assisted reproductive technologies (ART) has increased significantly in recent years (both known risk factors for ectopic pregnancy) and contemporary methods permit more accurate and earlier diagnosis than in the past (resulting in fewer ectopic pregnancies escaping detection), advances in detection and treatment of sexuallytransmitted infections have, at the same time, helped to prevent or limit related damage to the fallopian tubes (a major risk factor for ectopic pregnancy).12,14,15

Ectopic pregnancy rates are higher for blacks and other minorities than for whites in all age groups. For all races, the ectopic pregnancy rate increases progressively with age and is three to four times higher for women ages 35-44 than for those ages 15-24.5,16,17

Risk Factors

Many women with ectopic pregnancies have one or more recognized risk factors, but half of all women with ectopic pregnancy have none.18,19 A comprehensive analysis of casecontrol and cohort studies, using women with intrauterine pregnancies or nonpregnant women as controls, has helped to define their relative importance.20,21 22

Risk for ectopic pregnancy is increased as much as 10-fold for women with a previous ectopic pregnancy, compared to the general population. The overall risk for recurrence is approximately 15%, reflecting both the underlying tubal pathology that led to the first ectopic and the damage or trauma resulting from its treatment. Data from several studies indicate that the overall risk of recurrence is approximately 10% for women with one previous ectopic pregnancy and at least 25% for women having two or more.12,23,24,25,26 and 27 In a study comparing the recurrence risks associated with medical and surgical treatment for previous ectopic pregnancy, the risk of recurrence was approximately 8% after medical treatment with methotrexate (single-dose regimen), 10% after a salpingectomy, and 15% after a linear salpingostomy.28 Approximately 60% of women who have an ectopic pregnancy will subsequently achieve a successful intrauterine pregnancy.27,29,30

Risk for ectopic pregnancy is increased at least 3-fold for women with documented tubal pathology.20,21,36 In most cases, the damage results from sexually-transmitted infections, gonorrhea and chlamydia being the most common. Salpingitis damages the endosalpingeal mucosa, causing agglutination of mucosal folds and intraluminal adhesions that may entrap a migrating embryo, leading to ectopic implantation. Risk for ectopic pregnancy is increased 2-fold for women with circulating chlamydia antibodies and the majority of women with ectopic pregnancies have high levels.37,38,39 and 40 In a retrospective cohort study of women with previous documented chlamydia infection, the risk of hospitalization for ectopic pregnancy was increased more than 2-fold for women with two previous infections and more than 4-fold for those having three or more.41 Overall, women with surgically documented salpingitis have a 4-fold increased risk of ectopic pregnancy; the risk is approximately 10% after one episode of pelvic infection and increases progressively with each subsequent infection.42

Risk for ectopic pregnancy is increased at least 2-fold for women exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in utero.20,43,44 Numerous abnormalities of tubal anatomy have been observed in DES-exposed women, including shortened and convoluted tubes, constricted

fimbria, and paratubal cysts,45,46 but whether such abnormalities relate directly to the increased risk for ectopic pregnancy is unknown. DES was banned from future use in 1971 after its association with vaginal clear cell adenocarcinoma was recognized,47 but the youngest DES-exposed women are still in their late reproductive years and occasionally may be encountered.

fimbria, and paratubal cysts,45,46 but whether such abnormalities relate directly to the increased risk for ectopic pregnancy is unknown. DES was banned from future use in 1971 after its association with vaginal clear cell adenocarcinoma was recognized,47 but the youngest DES-exposed women are still in their late reproductive years and occasionally may be encountered.

The incidence and absolute risk of ectopic pregnancy is reduced with all methods of contraception.48,49 and 50 For any method, the ectopic pregnancy rate (pregnancy rate multiplied by the proportion of pregnancies with ectopic implantation) is lower than for women using no contraception (2.6 ectopic pregnancies/1,000 women-years). Among the most common methods of contraception, estrogen-progestin contraceptives and vasectomy are associated with the lowest absolute incidence of ectopic pregnancy (0.005 ectopic pregnancies/1,000 women-years). Rates are still very low, but about 60 times higher for tubal sterilization (0.32/1,000 women-years) and 200 times higher for the intrauterine device (IUD; 1.02/1,000 women-years).49,50 and 51 The risk for ectopic pregnancy in women who conceive while using barrier methods or oral contraceptives is no different than in pregnant controls.50

Most of the available data relating to the risk of ectopic pregnancy associated with the IUD derives from older studies involving IUDs no longer in use.21,52 Only two IUDs currently are marketed in the U.S., a copper-bearing device and the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS). Both are highly effective in preventing intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy with cumulative 5-year pregnancy rates that compare favorably with those observed in women after tubal sterilization (0.5-1%).53,54,55,56,57 and 58 However, if pregnancy does occur with an IUD in situ, the risk for ectopic pregnancy is high.59,60 Logically, the IUD should be expected to protect better against intrauterine than extrauterine implantation. Consequently, a greater proportion of pregnancies that occur will be ectopic. In one study of outcomes in 64 documented pregnancies in women with a LNG-IUS, one-half were ectopic.59

The U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization, involving more than 10,000 women who had a tubal sterilization, found that the 10-year cumulative probability of pregnancy after sterilization was 18.5/1,000 procedures.61 Data from the same cohort and others indicate that approximately one-third of all pregnancies resulting from sterilization failure are ectopic.62,63 and 64 The overall 10-year cumulative risk of ectopic pregnancy after tubal sterilization is approximately 7.3/1,000 procedures, but risk varies with the surgical method. Bipolar coagulation is associated with the highest risk (17.1/1,000 procedures) and postpartum partial salpingectomy with the lowest (1.5/1,000 procedures). For all methods other than postpartum partial salpingectomy, the probability of ectopic pregnancy is greater for women sterilized under age 30 than for older women. The 10-year cumulative probability of ectopic pregnancy for women sterilized by bipolar coagulation before age 30 (31.9/1,000 procedures) is more than 25 times the rate for postpartum partial salpingectomy at any age, which might be attributed to an increased incidence of tubo-peritoneal fistula at the distal end of the proximal tubal segment. For all methods combined, only about 20% of pregnancies occurring within 3 years after tubal sterilization are ectopic, but more than 60% of those occurring after 4 or more years are ectopic pregnancies.62,63,64 and 65

Ectopic pregnancies have been reported following emergency oral contraception. The best available evidence indicates that emergency contraception acts primarily by preventing or delaying ovulation or by preventing fertilization, rather than by inhibiting implantation. In theory, progestational agents may inhibit tubal motility and predispose to ectopic implantation, but none of the emergency oral contraceptive regimens in use appears to increase the risk.66,67,68 and 69

Risk for ectopic pregnancy is increased approximately 2-fold for infertile women.20,70,71,72,73 and 74 The association between infertility and previous pelvic infection and tubal pathology offers one obvious explanation. Ovulation-inducing drugs also are associated with increased risk, but whether unrecognized co-existing tubal factors or altered tubal function in stimulated cycles may be responsible is unclear.36,71,75

The risk of ectopic pregnancy may be increased as much as 2-fold in women who conceive via ART.76,77 Indeed, it is interesting to remember that the first pregnancy achieved with in vitro fertilization (IVF) and embryo transfer was ectopic.78 Although the mechanisms responsible have not been defined, natural migration into the tube and inadvertent direct tubal embryo transfer are the logical explanations. Women with tubal factor infertility or history of a previous ectopic pregnancy are at highest risk, presumably because embryos that migrate or are transferred into the fallopian tube inadvertently are less likely to return to the uterus before implantation. However, risk is increased even among women without tubal damage.12 It is possible that elevated hormone levels in IVF cycles may adversely affect tubal transport function.75,79 Higher volumes of transfer media or deep catheter insertion may predispose to accidental tubal transfer.76,80,81 Technically difficult transfers have been identified as another independent risk factor.82 Heterotopic pregnancies, in which one or more embryos implant both in the uterus and elsewhere, are rare in naturally conceived pregnancies (approximately 1 in 4,000-10,000 pregnancies), but far more common in infertile women who conceive after ovulation induction or IVF.77,83,84 and 85 The most recent data from the U.S. ART registry suggest that the risk of ectopic pregnancy associated with ART has decreased in recent years and now is no greater than in naturally conceived pregnancies; in 2007, only 0.7% of pregnancies resulting from ART using fresh nondonor oocytes or embryos were ectopic pregnancies.86

Overall, the risk for ectopic pregnancy is increased approximately 2-fold among women who smoke. Compared to never smokers, risk is increased by approximately 50% for past and light smokers (one to nine cigarettes daily) and rises progressively with heavier daily consumption.21,87 Studies in animals suggest that the mechanism responsible may involve a lower efficiency of oocyte-cumulus complex capture or a decreased tubal ciliary beat frequency induced by chemical components of cigarette smoke.88,89 There is no evidence to indicate any relationship between ectopic pregnancy and exposure to other chemical or physical agents.90

Early age at first intercourse and the number of lifelong sexual partners are associated with a mildly increased risk of ectopic pregnancy, presumably because of the higher probability of exposure to sexually-transmitted infections.20,21,91 Numerous studies have found an association between vaginal douching and ectopic pregnancy.92,93,94,95,96 and 97 Understandably, most have attributed the observation to an associated increased risk of ascending infection, but others have suggested that women with symptoms of genital infection are simply more likely to douche;98 a causal relationship between douching and ectopic pregnancy has not been established.

Pathogenesis of Ectopic Implantation

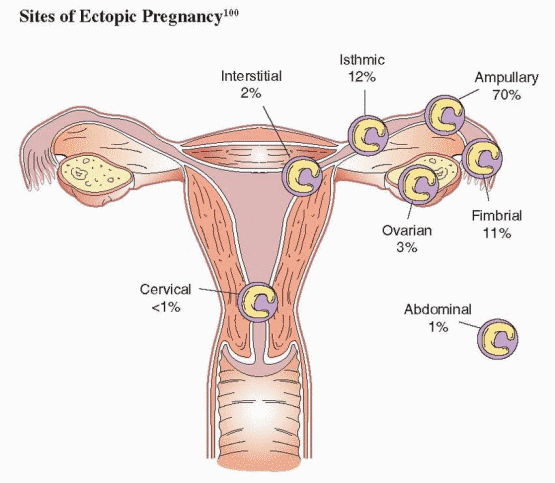

The fallopian tube is by far the most common site of ectopic implantation, accounting for more than 98% of all ectopic pregnancies. Overall, 70% of ectopic pregnancies are located in the tubal ampulla, 12% in the isthmus, 11% in the fimbria, and 2% in the interstitial (cornual) segment.99,100 Ectopic pregnancies in other sites are relatively rare and divided between ovarian, cervical, and abdominal sites.99,100

Anything that interferes with normal tubal transport mechanisms may predispose to ectopic pregnancy. It is possible, but unproven, that endocrine factors predisposing to premature implantation also may contribute to the pathogenesis of ectopic pregnancy.101 In histopathologic studies, post-inflammatory changes (chronic salpingitis, salpingitis isthmica nodosa) have been observed in up to 90% of fallopian tubes excised for ectopic pregnancy.102,103 and 104 Other abnormalities have included diverticula and foci of persistent decidual transformation. Any such underlying tubal pathology remains after conservative treatments, medical or surgical,

and may predispose to recurrence. The ectopic implantation itself may further damage the tube, depending on the extent of trophoblastic invasion. The endometrium in women with ectopic pregnancies usually exhibits decidual change, but also can have secretory or even proliferative histologic characteristics.105

and may predispose to recurrence. The ectopic implantation itself may further damage the tube, depending on the extent of trophoblastic invasion. The endometrium in women with ectopic pregnancies usually exhibits decidual change, but also can have secretory or even proliferative histologic characteristics.105

The histopathology of ectopic pregnancies varies with the site of implantation. In approximately half of ampullary ectopic pregnancies, trophoblastic proliferation occurs entirely within the tubal lumen and the muscularis remains intact.106 In the remainder, the trophoblast penetrates the tubal wall and proliferates in the loose connective tissue between the muscularis and the serosa.106,107 and 108 In most cases, the characteristic segmental dilation of the tubal ampulla is comprised mostly of coagulated blood rather than trophoblastic tissue. In contrast, ectopic implantations in the tubal isthmus typically penetrate the tubal wall relatively early,106 probably because the more muscular segment is less distensible. All ectopic pregnancies are not destined to rupture. In fact, many will resolve without intervention, presumably by spontaneous regression in situ or tubal abortion (expulsion via the fimbria).109

A number of studies have suggested that the prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities is increased in ectopic pregnancies and that intrinsic genetic abnormalities might in some way predispose to extrauterine implantation. However, more careful studies have failed to corroborate the finding.110 In fact, the prevalence of chromosomal aberrations among ectopic pregnancies appears almost identical to that expected (approximately 5%) when maternal and gestational age are considered.110,111 and 112

|

Diagnosis of Ectopic Pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy is associated with a classic triad of symptoms—delayed menses, vaginal bleeding, and lower abdominal pain—observed in women with both ruptured and unruptured ectopic pregnancies. In a series of 147 patients with ectopic pregnancy, the clinical presentation included abdominal pain in 99%, amenorrhea in 74%, and vaginal bleeding in

56%.113 Other symptoms associated with ectopic pregnancies include shoulder pain (from irritation of the diaphragm by blood in the peritoneal cavity), lightheadedness, and shock (from severe intra-abdominal hemorrhage). Unfortunately, there are no physical findings unique to ectopic pregnancy; similar symptoms are observed commonly in women with failing intrauterine pregnancies.114,115 Thankfully, the symptoms associated with advanced or ruptured ectopic pregnancy now are seldom seen, because most women present with mild pain or vaginal spotting well before tubal rupture and are identified promptly using methods that are more sensitive and specific than in the past.

56%.113 Other symptoms associated with ectopic pregnancies include shoulder pain (from irritation of the diaphragm by blood in the peritoneal cavity), lightheadedness, and shock (from severe intra-abdominal hemorrhage). Unfortunately, there are no physical findings unique to ectopic pregnancy; similar symptoms are observed commonly in women with failing intrauterine pregnancies.114,115 Thankfully, the symptoms associated with advanced or ruptured ectopic pregnancy now are seldom seen, because most women present with mild pain or vaginal spotting well before tubal rupture and are identified promptly using methods that are more sensitive and specific than in the past.

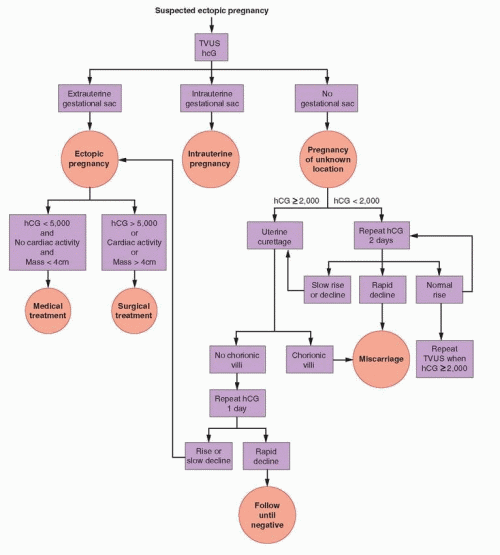

Clinical suspicion, based on an awareness of risk factors and the early symptoms of ectopic pregnancy, is the key to identifying women who merit prompt and careful evaluation. The ready availability of highly sensitive and specific assays for the b-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) has narrowed the differential diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy to include only pregnancy-related problems, including threatened, missed, complete, and incomplete abortions. In almost all women, one or more serum β-hCG determinations and transvaginal ultrasonography can establish or exclude the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy within a short time, if not immediately. Serum progesterone measurements and uterine curettage (when an early viable intrauterine pregnancy can be confidently excluded) also can be useful. Laparoscopy remains an important treatment option but rarely is any longer necessary for diagnosis alone.

Numerous diagnostic algorithms have been proposed for women suspected of having an ectopic pregnancy. All are based on the same basic concepts. Outpatient evaluation has been shown to be safe and effective for establishing a diagnosis of viable or nonviable intrauterine pregnancy or ectopic pregnancy. Accurate diagnosis is important because management of the three conditions is distinctly different.

The Serum β-hCG Concentration

HCG is secreted by the syncytiotrophoblast and becomes detectable in maternal serum as early as 8-10 days after ovulation in normal conception cycles. At or near the time of the first missed menses, serum levels between 50 and 100 IU/L are typical. Modern assays for the b-subunit of hCG are highly specific and sensitive, with detection limits below 5 IU/L. Consequently, virtually all women with suspected ectopic pregnancy who are not truly pregnant will have a negative test (no detectable hormone). False-negative tests are quite rare but, in the past, have been described in women with documented ectopic pregnancies.116,117 and 118 False-positive tests are equally rare and most often result from endogenous heterophilic antibodies, which bind to the animal antibodies (mouse, rabbit, goat) used in commercial immunometric assay systems and thereby mimick hCG immunoreactivity.119,120,121 and 122

Although rare, heterophilic antibodies are important to understand and to recognize because persistent false positive tests may be misinterpreted as evidence of ectopic pregnancy or gestational trophoblastic disease and lead to inappropriate evaluation and treatments having serious potential consequences.119 A false-positive hCG usually remains at the same level over time, neither increasing or decreasing. When the clinical presentation is uncertain or inconsistent with the test result, a true-positive hCG can be confirmed by 1) obtaining a similar result with a different assay method; 2) demonstrating hCG in the urine; and 3) obtaining parallel results with serial dilutions of the hCG standard and the patient’s serum.

Serum β-hCG concentrations rise predictably, at an exponential pace, during the early weeks of normal intrauterine pregnancy. In general, levels double every 1.4-2.1 days in early pregnancy and peak between 50,000 and 100,000 IU/L at 8-10 weeks of gestation.123,124 and 125 The rate of rise slows gradually as gestational age and β-hCG concentrations

increase,125 but during the brief interval when diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is most important (from 2 to 5 weeks after ovulation), the pattern is essentially linear. Evidence from studies performed before 1990 indicated that β-hCG levels should increase at least 66% every 2 days at concentrations below 10,000 IU/L in viable early intrauterine pregnancies, that few normal pregnancies (3-10%) ever exhibit an abnormal pattern, and most of those only transiently.123,124,126,127 However, in a more recent and careful analysis of data derived from evaluation of 287 women presenting with pain or bleeding and non-diagnostic ultrasonography who ultimately proved to have viable intrauterine pregnancies, the slowest or minimal rise observed was 24% after 1 day and 53% after 2 days.128 The median rise in β-hCG levels was 50% after 1 day, 124% after 2 days, and 400% after 4 days. These data indicate that the minimal normal increase in β-hCG concentrations for women with a viable intrauterine pregnancy (50% over 2 days) is “slower” than previously reported and that the criteria used to diagnose and treat abnormal pregnancies must therefore be more conservative than has been recommended in the past.128

increase,125 but during the brief interval when diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is most important (from 2 to 5 weeks after ovulation), the pattern is essentially linear. Evidence from studies performed before 1990 indicated that β-hCG levels should increase at least 66% every 2 days at concentrations below 10,000 IU/L in viable early intrauterine pregnancies, that few normal pregnancies (3-10%) ever exhibit an abnormal pattern, and most of those only transiently.123,124,126,127 However, in a more recent and careful analysis of data derived from evaluation of 287 women presenting with pain or bleeding and non-diagnostic ultrasonography who ultimately proved to have viable intrauterine pregnancies, the slowest or minimal rise observed was 24% after 1 day and 53% after 2 days.128 The median rise in β-hCG levels was 50% after 1 day, 124% after 2 days, and 400% after 4 days. These data indicate that the minimal normal increase in β-hCG concentrations for women with a viable intrauterine pregnancy (50% over 2 days) is “slower” than previously reported and that the criteria used to diagnose and treat abnormal pregnancies must therefore be more conservative than has been recommended in the past.128

Compared to the pattern observed in viable intrauterine pregnancies, β-hCG levels increase at a slower rate in most, but not all, ectopic and nonviable intratuterine pregnancies.123,129 In an analysis of data derived from evaluation of 200 women presenting to an emergency department who ultimately proved to have ectopic pregnancies, the median rise in serum β-hCG levels was 25% over 2 days, with 60% of patients having an increase and 40% exhibiting a decrease in β-hCG concentrations over that interval.129 Among those with rising levels, the mean increase (75% over 2 days) was smaller than the average for women with viable intrauterine pregnancies, and among those with declining concentrations, the decrease (27% over 2 days) was smaller than the average for women with completed spontaneous abortions. However, in 21% of women with ectopic pregnancies, the rise in β-hCG levels was greater than or equal to the minimal rise defined for women with viable intrauterine pregnancies, and in 8% of women with declining levels, the decrease was similar to that in women with completed spontaneous abortions.129 When levels do not rise normally, or fall, the pregnancy is almost certainly not viable, but may be ectopic or intrauterine. Serum hCG concentrations generally fall more rapidly in spontaneous abortions than in ectopic pregnancies, but the rate of decrease varies with the initial β-hCG concentration and is slower when levels are lower;130 overall, a decrease of less than 21% after 2 days or 60% after 7 days suggests retained products of conception or an ectopic pregnancy. Normally rising (>50% over 2 days) or rapidly falling (>20% over 2 days) β-hCG concentrations generally are reassuring, but do not exclude the possibility of ectopic pregnancy.129,131,132

When the risk of multiple gestation is relatively high, as in pregnancies resulting from ovarian stimulation or IVF, serial serum β-hCG determinations are more difficult to interpret confidently because the usual standards established for naturally conceived singleton pregnancies may not apply.133 In most multiple pregnancies, β-hCG levels are higher than in singleton gestations of the same age, reflecting the combined contributions of all gestations, but still rise at a normal rate.134 However, spontaneous pregnancy reductions are common in multiple gestations135 and heterotopic pregnancies are not altogether rare in stimulated women.77,84 One or more normally progressing intrauterine gestations may produce normal or increased levels of hCG, but a coexisting failing intrauterine or ectopic gestation likely will not. The β-hCG level at any one point in time will reflect the sum contributions from all gestations, normal and abnormal, intrauterine and ectopic. The normal hCG production from a viable intrauterine pregnancy easily can obscure the abnormally small contribution from another abnormal gestation. Alternatively, falling levels of hCG production from an ill-fated intrauterine or ectopic gestation may yield a slower than expected increase in serum concentrations even though a coexisting viable intrauterine gestation is progressing normally.

It also is important to note that inter-assay variation in β-hCG measurements ranges between 10% and 15% in most laboratories. Consequently, for most confident interpretation, serial concentrations should be performed in the same laboratory whenever possible. Alert to all possible scenarios, serum β-hCG concentrations must be interpreted very cautiously.

In sum, paired serum hCG concentrations alone cannot reliably distinguish ectopic pregnancies from abnormal or even normal intrauterine pregnancies. Consequently, the diagnostic evaluation of women with suspected ectopic pregnancy also must include transvaginal ultrasonography.

Transvaginal Ultrasonography

Numerous studies have helped to define the ultrasonographic characteristics of normal and abnormal early pregnancies.136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144 and 145 A gestational sac is the first ultrasonographic landmark in early intrauterine pregnancy. The sac consists of a sonolucent center with a thick echogenic ring, formed by the surrounding decidual reaction. Modern high frequency transducers (greater than 5 MHz) can detect a gestational sac earlier than older, lower frequency probes.146,147 Today, in pregnancies 5.5 weeks of gestation or greater, transvaginal ultrasonography should identify a viable intrauterine pregnancy with almost 100% accuracy.148,149 and 150 The absence of an intrauterine gestational sac 38 days or more after onset of menses or 24 days after conception is strong presumptive evidence for a nonviable pregnancy (ectopic or intrauterine).151 The criterion is useful when the menstrual history is well documented or conception occurs under close observation, but has little practical value when broadly applied, because irregular bleeding so often confounds attempts to define gestational age.152

When ultrasonography reveals no obvious intrauterine pregnancy, careful examination of the adnexal regions and cul-de-sac can provide additional useful information. Observation of a gestational sac with a yolk sac, embryo, or cardiac activity outside of the uterus establishes the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy and justifies immediate treatment. Evidence of an extrauterine gestation can be identified in up to 80-90% of ectopic pregnancies.145,149,153,154 and 155 A complex adnexal mass (not a simple cyst) or fluid in the cul-de-sac increases the probability of ectopic pregnancy but does not, by itself, make the diagnosis or justify immediate treatment.156,157 Any other result is simply inconclusive. Some have suggested that measurements of endometrial thickness have predictive value because the endometrium is thinner in women with ectopic pregnancy than in those with viable or nonviable intrauterine pregnancies.158 However, others have observed wide variations in endometrial thickness among women with suspected ectopic pregnancy or differences too small to have clinical utility.152,159 In a study involving 576 women presenting to an emergency department with complaints of pain and/or bleeding, the mean endometrial thickness was 9.56 ± 4.87 mm for women with ectopic pregnancies, 12.12 ± 6.0 mm for those with intrauterine pregnancies, and 10.19 ± 6.10 mm for women with spontaneous abortions.160 Although the extent of overlap among groups makes endometrial thickness a poor diagnostic test, a thickness greater than 21 mm with no evidence of an intrauterine gestational sac excludes ectopic pregnancy with 96% specificity.160

In many cases, transvaginal ultrasonography alone can establish the diagnosis in women with suspected ectopic pregnancies by revealing either an intrauterine or an extrauterine gestational sac. In the emergency room or other acute setting, ultrasonography is diagnostic in 70-90% of women with suspected ectopic pregnancy.15,143,144,148,150,161,162 When neither an intrauterine nor an extrauterine gestational sac is observed, defining a “pregnancy of unknown location,” the possibilities include an intrauterine pregnancy in which the gestational sac has not yet developed, collapsed, or completely aborted, and an ectopic pregnancy that is too small to be detected or has aborted. In some cases, uterine anomalies, fibroids, or a hydrosalpinx can obscure an intrauterine or extrauterine pregnancy; obesity also can prevent confident interpretation. Overall, at least 25% of women with an ectopic pregnancy present first with a pregnancy of unknown location,15,144,162 and 7-20% of women with that initial diagnosis prove ultimately to have an ectopic pregnancy.144

When available, color and pulsed Doppler ultrasonography can improve diagnostic accuracy. A small intrauterine gestational sac sometimes can be difficult to distinguish from the “pseudosac” (blood in the uterine cavity) observed in approximately 10% of women with ectopic pregnancy.163 The local vascular changes associated with a true gestational sac can help to differentiate the two.164,165 Vascular pulses and arterial flow velocity increase in early intrauterine pregnancy. The extent of peri-trophoblasic arterial flow correlates with gestational sac size and serum β-hCG concentrations. Blood flow in the arteries of the fallopian tube containing an ectopic pregnancy is 20-40% greater than in the contralateral tube.165,166 Similarly, adnexal masses may be distinguished by the characteristics of blood flow surrounding them. For example, the resistive index of ectopic pregancies also is higher than for corpus luteum cysts.167 However, the method has numerous diagnostic pitfalls, requires substantial technical expertise, and use of standard transvaginal ultrasonography and serum β-hCG concentrations usually is sufficient.168

When ultrasonography is inconclusive, serum β-hCG concentrations can serve as a surrogate marker for gestation age and help determine whether an intrauterine gestational sac should or should not be present. The concept of a “discriminatory zone,” the minimum serum β-hCG concentration above which a gestational sac always should be detected in a viable intrauterine pregnancy, revolutionized the diagnostic approach to women with suspected ectopic pregnancy. When the concept was first introduced in 1981, transabdominal ultrasonography was the standard and the discriminatory zone was 6,000-6,500 IU/L.169

With the development of endovaginal transducers of higher frequency, the discriminatory zone decreased progressively and now generally ranges between 1,500 and 3,000 IU/L.27,157,170,171 and 172 In one study, 185 of 188 intrauterine pregnancies (98%) among women with a β-hCG concentration greater than 1,500 IU/L were imaged.15 In any given center, the discriminatory zone or value will depend on the experience of the examiner and on the type of equipment in use.157,170,171 Using a higher, more conservative threshold value (e.g., 2,000 or 2,500 IU/L) helps to minimize the risk of diagnostic error, but also may delay diagnosis of an ectopic pregnancy. The threshold value of 2,000 IU/L is suggested in the algorithm appearing in this chapter. Identification of an intrauterine gestational sac excludes the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy, except in circumstances wherein a heterotopic pregnancy or a pregnancy in a rudimentary uterine horn must be considered.

When the β-hCG concentration is clearly above the discriminatory value, attention should focus on establishing the location of the pregnancy, now deemed nonviable by virtue of having failed to observe an intrauterine gestational sac.27,143,173 The absence of an intrauterine gestational sac is strong, but not conclusive, evidence for an ectopic pregnancy.15 Other possibilities must be considered before treatment begins. In incomplete abortions, an intrauterine gestational sac may be absent or difficult to recognize. In very recent complete abortions, serum β-hCG levels may be declining rapidly, but still elevated. Even a viable intrauterine pregnancy cannot be excluded entirely when there is good reason to suspect a multiple gestation. Consequently, even when the β-hCG concentration is above the discriminatory value, a repeated β-hCG measurement in 1-2 days merits consideration in women at low risk for ectopic pregnancy with few or no symptoms, to identify those who might otherwise receive unnecessary treatment, or worse, harmful treatment. A rapidly falling β-hCG level indicates a resolving nonviable pregnancy and can be followed until undetectable. A normally rising β-hCG concentration indicates the need for repeated ultrasonography to exclude the possibility of a viable intrauterine pregnancy not detected previously and that otherwise might be exposed to methotrexate, resulting in inadvertent termination or in severe embryopathy (intrauterine growth restriction, microcephaly, and facial, cranial, and skeletal abnormalities).174,175,176,177,178 and 179

In patients with initial β-hCG values below the discriminatory zone, the absence of an intrauterine gestational sac is inconclusive; clinical signs (hemodynamic instability), symptoms (pain), and other sonographic findings (extrauterine gesational sac, complex adnexal mass, cul-de-sac fluid) must guide clinical management.180 In some women, clinical

circumstances will demand an immediate and definitive surgical diagnosis. Women with no or few symptoms require close follow-up and serial evaluations until the possibility of ectopic pregnancy can be excluded.148,157,181,182 Repeated measurements of serum β-hCG at 2-day intervals help to distinguish nonviable pregnancies from early viable intrauterine gestations not yet large enough to detect.

circumstances will demand an immediate and definitive surgical diagnosis. Women with no or few symptoms require close follow-up and serial evaluations until the possibility of ectopic pregnancy can be excluded.148,157,181,182 Repeated measurements of serum β-hCG at 2-day intervals help to distinguish nonviable pregnancies from early viable intrauterine gestations not yet large enough to detect.

In women with normally increasing β-hCG levels below the discriminatory value, ultrasonography should be performed or repeated when levels have risen above the discriminatory value. After 2-7 days, ultrasonography can be expected to demonstrate the location of the pregnancy in the large majority of cases.144 Occasionally, a new adnexal abnormality (complex mass) or increasing clinical symptoms may demand a definitive surgical diagnosis when a desired viable intrauterine pregnancy cannot be confidently excluded.157,181,182 Women with rapidly decreasing β-hCG concentrations warrant only continued observation because the likelihood of ectopic pregnancy is low.183 Nonetheless, serial measurements should be obtained until levels are no longer detectable, which can take up to as much as 6 weeks.12 Those in whom an intrauterine pregnancy has not been documented remain at risk for rupture of an ectopic pregnancy until β-hCG is no longer detectable.148 Slowly declining or abnormally rising β-hCG levels indicate a nonviable pregnancy that still may be ectopic or intrauterine, but virtually exclude the possibility of a viable intrauterine pregnancy. The same is true when β-hCG levels rise to a concentration clearly above the discriminatory value and ultrasonosgraphy is again inconclusive (no intrauterine or extrauterine gestational sac). In either case, medical treatment could be offered safely, but a presumed diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy will be inaccurate, and treatment unnecessary, in up to 40% of women.184 Therefore, many prefer to perform curettage to distinguish the remaining 2 possibilities (discussed below).

A conservative approach to pregnancies of unknown location prevents inappropriate intervention in a viable intrauterine pregnancy. Although it risks a modest delay in diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy and a small possibility of rupture, evidence from several studies indicates that a conservative diagnostic approach rarely compromises the care of women with pregnancies of unknown location.150,162,181,185,186,187,188 and 189 Consequently, every reasonable effort should be made to establish a definite diagnosis.

The Serum Progesterone Concentration

Serum progesterone concentrations generally are lower in ectopic pregnancies than in viable intrauterine pregnancies.190,191,192 and 193 The most logical explanation is that ectopic pregnancies are almost always accompanied by abnormally low levels of hCG production. Whereas the hCG secreted by ectopic gestations is chemically and biologically indistinct from that in intrauterine pregnancies,194,195 production rates are lower, primarily because ectopic trophoblast proliferates more slowly and is less biologically active.196,197 Corpus luteum progesterone production in early pregnancy is regulated primarily by the rate of change in serum hCG concentrations.195 Under normal circumstances, the exponential increase in hCG levels ensures that LH/hCG receptors are occupied to the extent corresponding with maximal stimulation as the corpus luteum matures and the number of available receptors increases. In contrast, few ectopic pregnancies exhibit normal hCG production rates for very long. Consequently, progesterone secretion may increase normally at first but inevitably slows, resulting in lower serum concentrations.198,199 There is no evidence to support the alternative hypothesis that poor luteal function in ectopic pregnancy results from reduced or absent production of other trophic feto-placental factors distinct from hCG.195

Serum progesterone levels associated with early normal and abnormal intrauterine pregnancies and ectopic pregnancies vary widely and overlap to a large extent. Consequently,

whereas a grossly low serum progesterone concentration is unlikely to be associated with a viable intrauterine pregnancy, it cannot distinguish an ectopic pregnancy from a failed intrauterine gestation.9,14,200,201,202,203 and 204 The probability of a viable intrauterine pregnancy increases with the serum progesterone concentration. Levels greater than 20 ng/mL almost always indicate a normal intrauterine pregnancy. Conversely, concentrations less than 5 ng/mL almost always indicate a nonviable pregnancy, which may be either ectopic or intrauterine.9,14 Unfortunately, 50% of ectopic pregnancies, nearly 20% of spontaneous abortions, and almost 70% of viable intrauterine pregnancies are associated with serum progesterone levels between 5 and 20 ng/mL.205,206 Moreover, because exceptions to the norm can and do occur, neither threshold value is entirely reliable in an individual woman. Only about 0.3% of women with viable intrauterine pregnancies have a serum progesterone level under 5 ng/mL, but approximately 3% of those with ectopic pregnancies have progesterone concentrations above 20 ng/mL.201,206 The utility of serum progesterone measurements in the evaluation of women with suspected ectopic pregnancy is further limited when conception results from treatments involving ovarian stimulation. Higher than usual progesterone levels logically may be expected because treatment often yields more than a single corpus luteum.207

whereas a grossly low serum progesterone concentration is unlikely to be associated with a viable intrauterine pregnancy, it cannot distinguish an ectopic pregnancy from a failed intrauterine gestation.9,14,200,201,202,203 and 204 The probability of a viable intrauterine pregnancy increases with the serum progesterone concentration. Levels greater than 20 ng/mL almost always indicate a normal intrauterine pregnancy. Conversely, concentrations less than 5 ng/mL almost always indicate a nonviable pregnancy, which may be either ectopic or intrauterine.9,14 Unfortunately, 50% of ectopic pregnancies, nearly 20% of spontaneous abortions, and almost 70% of viable intrauterine pregnancies are associated with serum progesterone levels between 5 and 20 ng/mL.205,206 Moreover, because exceptions to the norm can and do occur, neither threshold value is entirely reliable in an individual woman. Only about 0.3% of women with viable intrauterine pregnancies have a serum progesterone level under 5 ng/mL, but approximately 3% of those with ectopic pregnancies have progesterone concentrations above 20 ng/mL.201,206 The utility of serum progesterone measurements in the evaluation of women with suspected ectopic pregnancy is further limited when conception results from treatments involving ovarian stimulation. Higher than usual progesterone levels logically may be expected because treatment often yields more than a single corpus luteum.207

Some have suggested that progesterone levels less than 5 ng/mL identify women in whom uterine curettage can be performed safely in search of chorionic villi to distinguish ectopic pregnancies from spontaneous abortions.9,208 Using that approach, the probability of inappropriate intervention in a viable intrauterine pregnancy is indeed very low, but even that small risk may be unacceptably high. In sum, serum progesterone measurements generally add very little to the diagnostic evaluation of women suspected of having an ectopic pregnancy.

Uterine Curettage

When ultrasonography is inconclusive and β-hCG concentrations are above the discriminatory zone, or below the threshold value and rise abnormally, plateau, or fall, the possibility of a viable intrauterine pregnancy is all but excluded; an early multiple pregnancy or an error in performing or interpreting ultrasonography are the only exceptions. Uterine curettage can help to distinguish ectopic from nonviable intrauterine pregnancies, but still should be applied selectively. Curettage clearly is inappropriate when there is any possibility of interrupting a viable intrauterine pregnancy and is unnecessary in women with rapidly falling β-hCG levels. Recovery of chorionic villi excludes ectopic, but not heterotopic pregnancy. The absence of villi makes the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy likely, although a very recent complete abortion or a technical failure to obtain or to recognize villi also is possible; chorionic villi are not detected by histopathology in 20% of elective terminations of pregnancy.209 If curettage is not performed and ectopic pregnancy is presumed, misdiagnosis leading to unnecessary treatment will occur in approximately 40% of women.184 Therefore, uterine curettage is recommended for women with nonviable pregnancies of unknown location, to distinguish an ectopic pregnancy that requires treatment from a nonviable intrauterine pregnancy that does not.

If they are present, gross inspection of the curettings in saline will reveal obvious chorionic villi about half of the time. Frozen section and histologic examination will demonstrate villi in 80-90% of specimens obtained from women with spontaneous abortion, and is recommended when available, to help avoid delays in establishing a definite diagnosis. Otherwise, a postoperative serum β-hCG may be obtained. A 20% or greater decrease in the β-hCG level within 12-24 hours suggests strongly that the patient had a nonviable intrauterine gestation that was removed.209,210 Conversely, a slower rate of decrease, or an increase, strongly suggests an ectopic pregnancy.12 Women with declining levels can be monitored with serial β-hCG concentrations until no longer detectable or until the

pathology report confirms the presence of chorionic villi. In a series of 111 women with nonviable pregnancies of unknown location that had curettage, villi were detected in 37% overall and in 51% of those whose initial β-hCG level was greater than 1,500 IU/L.184

pathology report confirms the presence of chorionic villi. In a series of 111 women with nonviable pregnancies of unknown location that had curettage, villi were detected in 37% overall and in 51% of those whose initial β-hCG level was greater than 1,500 IU/L.184

|

Uterine curettage is costly, requires an operating room and anesthesia in some institutions, and is associated with a small risk of a complication. By comparison, uterine aspiration using a pipelle is simple to perform in the outpatient setting and minimally invasive. The results obtained with pipelle aspiration and curettage generally correlate extremely well when they are performed for suspected endometrial pathology (hyperplasia or carcinoma).

Unfortunately, pipelle biopsy is not an effective substitute for curettage in the evaluation of women with suspected ectopic pregnancy. The sensitivity of pipelle biopsy for detecting chorionic villi is unacceptably poor, ranging between 30% and 60%.211,212 If treatment is based on results obtained with a pipelle biopsy, up to one in three women with a miscarriage may receive unnecessary and inappropriate medical or surgical treatment. The higher sensitivity of curettage (80-90%) yields a misdiagnosis of ectopic pregnancy in no more than approximately 2 in 10 women with a spontaneous abortion.212,213 and 214 Although rare, it is useful to remember that chorionic villi sometimes may be found in curettings from women with an ectopic pregnancy.215

Some advocate empiric medical treatment for all women with nonviable pregnancies of unknown location, viewing treatment as more practical and less invasive than curettage.187,216 A decision analysis found neither approach superior, but also observed that empiric treatment yields little savings, does not reduce complications, and clouds the prognosis for future fertility and the risk of repeat ectopic pregnancy.217 We favor curettage over empiric medical treatment, preferring to avoid unnecessary treatment and the uncertainties that result from a presumptive diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy.

Screening for Ectopic Pregnancy

Transvaginal ultrasonography and serum β-hCG determinations have proven diagnostic value in the evaluation of symptomatic women with suspected ectopic pregnancy. Not surprisingly, some have advocated applying the same diagnostic tools to screen asymptomatic women at increased risk for ectopic pregnancy. In practice, women at risk might be instructed to contact their clinician as soon as pregnancy is suspected and, if confirmed, receive careful monitoring with serial β-hCG determinations and timely ultrasonography. The alternative is to evaluate only those in whom clinical symptoms of pain or vaginal bleeding emerge. The rationale for screening at-risk women is that early diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy allows early intervention and non-invasive treatment that may help to minimize tubal damage and to reduce costs.218,219 However, widespread screening of symptom-free women is costly and increases the likelihood of false-positive diagnoses of ectopic pregnancy that may result in unnecessary or inappropriate medical or surgical treatment.219,220

From both a clinical and economic perspective, the cost-effectiveness of screening depends on the prevalence or risk of ectopic pregnancy in the population chosen for screening. If the risk is low, very few ruptured ectopic pregnancies will be prevented and the costs of screening far exceed the benefits and savings resulting from early diagnosis and medical instead of surgical treatment. If uterine curettage is performed for all nonviable pregnancies identified through screening, the costs are even greater because the large majority will be spontaneous abortions that otherwise might be managed expectantly.220,221,222 and 223 If the risk is high, the benefits and savings realized through prevention of ruptured ectopic pregnancies are proportionately greater and better justify the costs associated with screening.

Results of a decision analysis suggest that screening probably is justified when the risk of ectopic pregnancy is approximately 8% or higher. At that risk level, screening may be expected to prevent one to two ruptured ectopic pregnancies and to yield less than one false positive diagnosis for every 100 women screened.220 Accepting a 2% background rate of ectopic pregnancy and considering the increased incidence associated with certain risk factors, screening seems justified for women with previous tubal surgery or ectopic pregnancy and those with known tubal pathology or who conceive with an IUD in situ or after a

sterilization procedure. Screening is more difficult to justify for women in whom a history of infertility or pelvic infection is the only risk factor.

sterilization procedure. Screening is more difficult to justify for women in whom a history of infertility or pelvic infection is the only risk factor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree