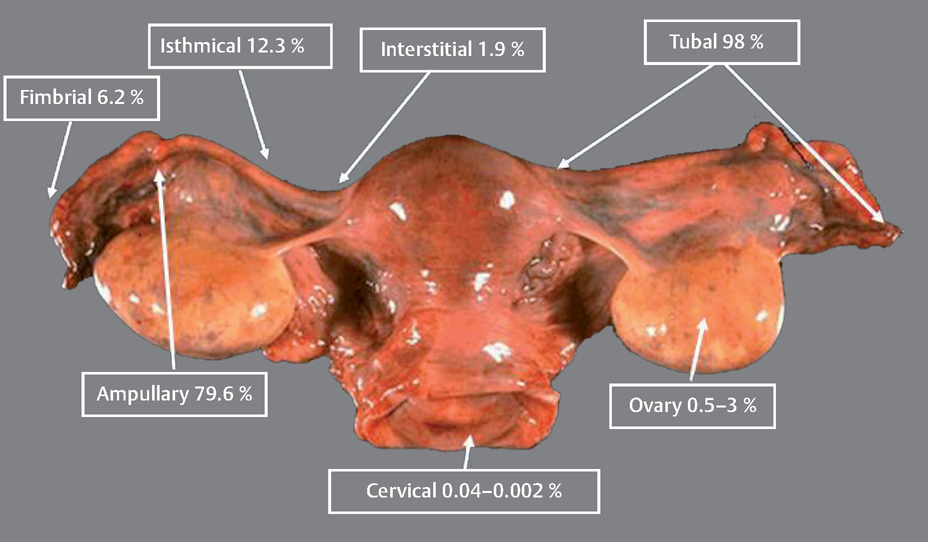

13 Ectopic Pregnancies Eyal Sheiner and Arnon Wiznitzer Ectopic pregnancy (EP) is a major health problem for women of reproductive age and is the leading cause of pregnancy-related death during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy. EP accounts for about 9% of all pregnancy-related deaths, and its incidence is higher for non-White women. This disparity increases with age. Accurate diagnosis and treatment of EP significantly decreases the risk of death and optimizes subsequent fertility. Ectopic pregnancy (EP) refers to implantation of a fertilized ovum outside the uterus. The most common site of EP implantation is the fallopian tubes, accounting for about 98% of all EP cases. The majority of EPs (79.6%) are implanted in the ampullary part of the fallopian tube, approximately 12.3% implant in the isthmus, 6.2% in the fimbria, and 1.9% in the interstitial part (Fig. 13.1). In rare cases implantation can occur in other ectopic sites including the ovary, uterine cervix (i. e., cervical pregnancy), and abdomen. Coexistent intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancies are referred to as heterotropic pregnancy. The most common symptoms of EP are abdominal or pelvic pain accompanied with vaginal bleeding. The best diagnosis is based on the positive visualization of an extrauterine pregnancy outside the uterus. However, this is not seen in all cases. About 90% of EPs may be visualized using transvaginal sonography within 5 weeks of the last menstrual period. Another method of EP detection is to measure the level of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG). When the HCG level exceeds the transvaginal discriminatory zone (1000–2000 mIU/mL), it suggests the absence of an intrauterine gestational sac, and EP. It also may also suggest a failed intrauterine pregnancy. However, the combination of positive HCG and transvaginal ultrasound scan has a positive predictive value of 95% for an EP. If an intrauterine pregnancy is detected, this tends to exclude a diagnosis of EP, because coexisting intrauterine and extrauterine pregnancies (heterotopic) following spontaneous cycles are rare, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 30 000. There has been a significant increase in the number of cases of EP in the past several decades in developed countries. In the United States, for example, a sixfold increase in the number of cases of EP was noted between 1970 and 1992. The rate varies between 6 and 30 per 1000 pregnancies. However, with in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles, the rate can be as high as 4.5%. The most common initiators of EP are tubal obstruction and injury. Previous pelvic inflammatory disease, especially due to Chlamydia trachomatis, is the leading risk factor for ectopic pregnancy. Other factors associated with an increased risk of EP include prior ectopic pregnancy, a history of infertility (and specifically IVF), cigarette smoking (which causes alterations in tubal motility and ciliary activity), prior tubal surgery, exposure to diethylstilbestrol (which alters fallopian tube morphology), non-White women, and advanced maternal age. Fig. 13.1 Various locations where ectopic pregnancies can occur and their relative ratio of occurrence at those sites. Women can be protected from developing an EP by intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUDs), progesteroneonly contraceptives, and sterilization. Nevertheless, if a woman who has been sterilized or is a current user of an IUD or progesterone-only contraceptives becomes pregnant, her risk for an EP is increased 6 to 10-fold, since these methods of contraception provide greater protection against intrauterine pregnancies than EPs. Table 13.1 summarizes risk factors for EP. The classic symptom triad of EP includes amenorrhea, irregular bleeding, and lower abdominal pain. The triad is present in only half of patients and most commonly when rupture has occurred. The physical examination should include measurements of vital signs. Abdominal and pelvic tenderness, especially cervical motion tenderness, are common when rupture has occurred (and present in about 75% of patients). However, pelvic examination before rupture is usually nonspecific, and a palpable pelvic mass on bimanual examination is established in less than half of the cases. The accuracy of the initial clinical evaluation before rupture is less than 50% and additional tests are required in order to differentiate EP from early intrauterine pregnancy. Work-up includes first ruling out a normal intrauterine pregnancy.

Definition

Diagnosis

Prevalence

Etiology and Pathophysiology

History

Physical Examination

| Risk factors | Predisposing conditions |

| Tubal obstruction and injury | Previous pelvic inflammatory disease, (especially Chlamydia trachomatis) |

| Prior ectopic pregnancy | |

| A history of infertility (especially IVF) | |

| Prior tubal surgery, tubal ligation | |

| Diethylstilbestrol exposure | |

| Non-White ethnicity | |

| Advanced maternal age | |

| Cigarette smoking | |

| Multiple partners |

Ultrasonography

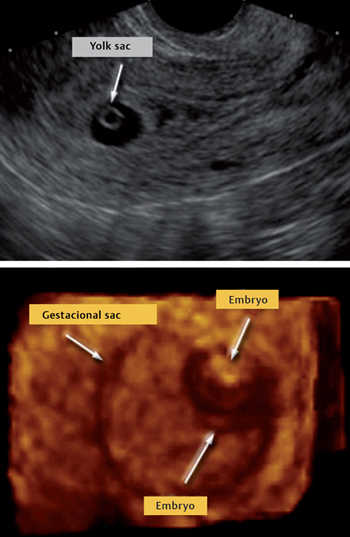

The early sonographic appearance of a normal gestational sac is characterized by signs of a double decidual sac (i. e., two concentric echogenic rings separated by a hypoechogenic space) (Fig. 13.2). The presence of the characteristic double decidual sac is important in helping the physician diagnosis an intrauterine pregnancy at a very early stage as well as to exclude EP.

However, an intrauterine pseudo-sac can be seen in some cases of EP, owing to intrauterine fluid or blood collection. A pseudo-sac is a uterine sac without a double decidual ring or a yolk sac.

Laboratory Assessment: β-HCG measurements

The first stage in the evaluation of women with a suspected EP is to determine whether the patient is pregnant. The enzyme immunoassay for HCG is positive in virtually all cases of EP. A “discriminatory cutoff of β-HCG” means the level at which a normal intrauterine pregnancy can reliably be visualized by ultrasound scanning. A viable intrauterine pregnancy should be seen by transvaginal sonography at HCG levels of about 1500 mIU/mL.

Fig. 13.2 Longitudinal ultrasound view of the uterus, gestational sac and yolk sac (top) and visualization of the embryo at the end of week 5 (bottom)

The level of HCG increases during gestation and reaches a peak of approximately 100 000 mIU/mL at 6–10 weeks. It then decreases and remains stable at approximately 20 000 mIU/mL. A 66% rise in the HCG level over a 48-hour period represents the lower limit of normal values for viable intrauterine pregnancy. Indeed, there is consensus that the predictable rise in serial β-HCG values is markedly different from the slow rise or plateau due to an EP.

Limitations of serial HCG testing include its inability to distinguish a failing intrauterine pregnancy from an ectopic pregnancy and the inherent 48-hour delay. Assays of serial HCG levels are typically required only when an initial ultrasound scan fails to detect either intrauterine or extrauterine pregnancy.

Serum Progesterone

The utility of measuring serum progesterone levels for diagnosing EP is still being debated. A baseline serum progesterone level of less than 20 nmol/L can be used to identify abnormal pregnancy (either intrauterine or extrauterine) with a positive predictive value of ≥95%.

Among pregnant patients with serum progesterone values of less than 5 nmol/L, 85% have spontaneous abortions, 0.16% have viable intrauterine pregnancies, and 14% have ectopic pregnancies. However, serum progesterone levels cannot distinguish ectopic pregnancy from spontaneous abortion. Thus, progesterone levels at defined times can be used to predict the immediate viability of a pregnancy, but cannot be used reliably to predict its location.

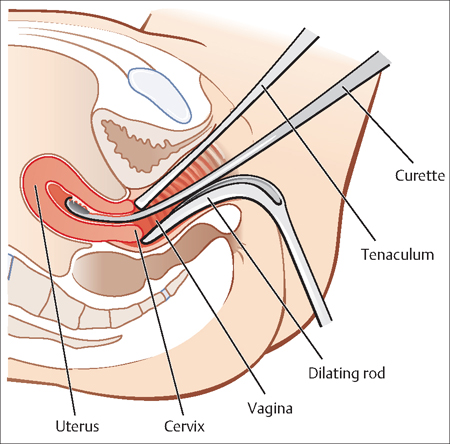

Dilatation and Curettage

When serial HCG values do not rise or fall appropriately, an abnormal gestation exists. When the pregnancy has been confirmed to be nonviable, a uterine dilation and curettage can be performed to obtain products of conception. It also can distinguish between an ectopic pregnancy and a miscarriage, when ultrasound scanning is not sufficient (Fig. 13.3).

Once tissue is obtained by curettage, it can be added to saline in order to investigate whether the sample foats. Visualization of villi in the tissue obtained indicates the occurrence of spontaneous intrauterine abortion. Because foating of the material is not 100% accurate, histological verification or serial HCG level measurement is needed.

Fig. 13.3 For a dilation and curettage (D&C), the patient lies on her back, and a weighted retractor is placed in the vagina A dilator is used to open the cervix, and a curette is used to scrape the inside of the uterus.

The absence of chorionic villi in the curettage specimen indicates the possibility of an EP.

Treatment Options

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree