Background

Early-onset preeclampsia is associated with adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. For women who consider another pregnancy after one complicated by early-onset preeclampsia, the likelihood of recurrence and the subsequent pregnancy outcome for themselves and their babies are pertinent considerations.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to determine the subsequent pregnancy rate after a nulliparous pregnancy that was complicated by early-onset preeclampsia and among those who have a subsequent pregnancy, the risk of recurrence by gestational week, and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Study Design

This was a population-based record linkage cohort study. The study population included nulliparous women with a singleton pregnancy and early-onset preeclampsia (<34 weeks gestation) who gave birth in New South Wales Australia from 2001–2010 (the index birth), with follow-up data for a subsequent birth through 2012. Early-onset in the index birth was further categorized as <28 vs 28–33 weeks gestation. Subsequent pregnancy outcomes that were assessed included the pregnancy rate, preeclampsia recurrence, and maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality rates. The risk of preeclampsia necessitating delivery at each gestational week for women who were at risk was plotted, and the net gain or loss of gestational age when comparing the index with the subsequent pregnancy was calculated.

Results

Among 361,031 nulliparous women with singleton pregnancies, 1473 (0.4%) had early-onset preeclampsia. Women with early-onset preeclampsia in their first pregnancy had a lower subsequent pregnancy rate (59.7%) than women without preeclampsia (67.7%). Of the 758 women with a subsequent singleton birth, 256 (33.8%) experienced preeclampsia in the next pregnancy; 57 women (7.5%) with recurrent early-onset preeclampsia were included. Cumulative rates of preeclampsia in the subsequent pregnancy were higher at every gestation from 23 weeks gestation when the index birth was <28 weeks compared with 28–33 weeks gestation. The cumulative rate and gestation-specific risk of recurrent preeclampsia rose most steeply at 32–38 weeks gestation. Most women (94.6%) progressed to a later gestational age in their subsequent pregnancy. The median overall increase in gestational age at delivery was 6 weeks (interquartile range, 4–8); among women with recurrent preeclampsia, the median increase was 5 weeks (interquartile range, 2–7). Women with index birth <28 weeks gestation compared with 28–33 weeks gestation were more likely to deliver preterm (38.8% vs 28.7%; relative risk, 1.35; 95% confidence interval, 1.04–1.75) and have a perinatal death (4.3% vs 1.2%; relative risk, 3.46; 95% confidence interval, 1.15–10.39) at the subsequent birth, but live born infants had similar rates of severe morbidity (17.1% vs 15.0%; relative risk, 1.14; 95% confidence interval, 0.73–1.79).

Conclusion

Women with early-onset preeclampsia in a first pregnancy appear less likely than women without preeclampsia to have a subsequent pregnancy. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in the subsequent pregnancy are generally better than in the first; most women will not have recurrent preeclampsia, and those who do usually will give birth at a greater gestational age compared with their index birth.

Early-onset preeclampsia that results in delivery of an infant at <34 weeks gestation complicates approximately 4 per 1000 pregnancies in nulliparous women. Many of these mothers and babies are at increased risk of severe adverse outcomes that include acute renal or hepatic failure, antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage, stroke, maternal death, intrauterine growth restriction, and perinatal death. Long-term, the burden of preterm birth is immense, particularly in terms of neurodevelopmental impairment, impaired learning, cerebral palsy, and need for special care resources.

For women, the psychosocial sequelae of early-onset preeclampsia and the complications that are associated with preterm birth are often significant. Despite the desire for another child, many women are anxious about becoming pregnant again because of concerns of recurrent complications in a next pregnancy. Counseling women after a first affected pregnancy is a difficult but important task; particularly because a negative birth experience may influence future reproduction. For women who consider another pregnancy after one complicated by early-onset preeclampsia, the likelihood of recurrence and the subsequent pregnancy outcome for them and their babies are pertinent considerations. Reported recurrence rates of hypertensive disorders that necessitate delivery at <34 weeks gestation in the second pregnancy vary widely (3–62%), mainly because of small numbers and heterogeneity across studies. Furthermore, there is a lack of reporting of major perinatal or maternal morbidity. The effect of gestational age in the index pregnancy has been examined, but not how gestational age was distributed in women who had recurrent hypertensive disease. The rate of recurrent preeclampsia that necessitates delivery during each week of the gestational period remains undescribed. For a woman who has had preeclampsia at <34 weeks gestation, an important question is whether she will experience preeclampsia early again or can she expect her pregnancy to continue closer to term. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the subsequent pregnancy rate after a nulliparous pregnancy with early-onset preeclampsia and, among those who have a subsequent pregnancy, to determine the risk of recurrence by gestational week and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study population

The study population included nulliparous women with a singleton pregnancy and early-onset preeclampsia who gave birth in New South Wales (NSW), Australia, from 2001–2010 (the “index birth”). These women were followed longitudinally to subsequent, consecutive (2nd) births at ≥20 weeks gestation (“subsequent birth”) up to December 2012 (minimum 2-year follow up). Losses at <20 weeks gestation were not eligible for the recurrence study but are reported in the overall rate of women who had subsequent pregnancies.

Data sources

Data were obtained from 2 linked population health datasets: the NSW Perinatal Data Collection (referred to as “birth records”) and the NSW Admitted Patient Data Collection (referred to as “hospital records”). The Perinatal Data Collection is a statutory surveillance system of all births in NSW of ≥20 weeks gestation or ≥400-g birthweight. Information on maternal characteristics, pregnancy, labor, delivery, and infant outcomes are recorded by the attending midwife or doctor. The Admitted Patient Data Collection is a census of all NSW inpatient hospital discharges from public and private hospitals and includes demographic and episode-related data; diagnoses and procedures are coded for each admission from the medical records according to the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Australian Modification. Hospitalizations for early pregnancy loss can be identified from the Admitted Patient Data Collection. Longitudinal linkage of birth and hospital records was undertaken by the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage. The linkage proportion for maternal hospital and birth records is 98.1%. The researchers were provided with anonymized data. Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (2002/12/430).

Early-onset preeclampsia definition and ascertainment

Early-onset preeclampsia was defined as a hospital record with a diagnosis of preeclampsia and delivery at <34 weeks gestation. The exact timing of preeclampsia onset was unknown, and delivery <34 weeks gestation was used as a marker of severe early-onset disease. Preeclampsia diagnoses were obtained from the longitudinally linked hospital records (physician recorded diagnosis coded according to the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Australian Modification). Preeclampsia is reported with 100% sensitivity and positive predictive value when associated with delivery at <34 weeks gestation. During the study period, preeclampsia was defined as de novo onset of hypertension (systolic blood pressure, ≥140 mm Hg, and/or diastolic blood pressure, ≥90 mm Hg) from 20 weeks gestation onwards and with ≥1 of proteinuria, renal insufficiency, liver involvement, neurologic complications, hematologic complications, or fetal growth restriction.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was the recurrence rate of early-onset (<34 weeks gestation) preeclampsia. Other outcomes included the subsequent pregnancy rate and from among the consecutive subsequent singleton births at ≥20 weeks gestation: overall preeclampsia rate (any gestation), antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage, severe maternal morbidity, maternal length of stay (birth admission) ≥7 days, small-for-gestational age infant (birthweight, <10th percentile), 5-minute Apgar score of <7, severe neonatal morbidity, and perinatal death. Severe maternal and neonatal morbidity were determined with the use of composite outcome indicators that have been developed and validated for use in population health datasets and include both life-threatening conditions and procedures that are associated with severe morbidity. Few records were missing data from the subsequent birth; 2 records were missing birthweight percentile, and 1 record was missing an Apgar score.

The prevalence of the following established risk factors for preeclampsia at the index birth was obtained from the birth records or from hospital records during and before pregnancy: maternal age, Asian ethnicity (based on maternal country of birth), smoking during pregnancy, chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus (pregestational or gestational), morbid obesity, renal disease, autoimmune diseases (including antiphospholipid syndrome), interpregnancy interval, and use of assisted reproductive technology (ART). For the index birth, there were no records with missing data.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics and relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to compare characteristics of index births of women with early-onset preeclampsia with those women without preeclampsia and to compare subsequent pregnancy outcomes for index births at 20 0 –27 6 and 28 0 –33 6 weeks gestation. We plotted the rate of women undelivered by gestational age for women with recurrent preeclampsia and in a comparison population (women with second singleton births from 2001–2012 with no history of preeclampsia). We also determined the rate of preeclampsia recurrence for each week of gestation among pregnancies at risk (ie, among women still pregnant at the beginning of each gestational week).

Results

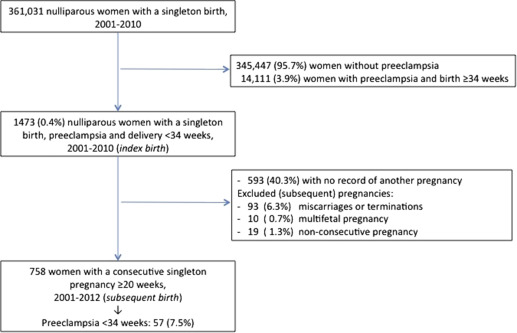

Among 361,031 nulliparous women with singleton pregnancies from 2001–2010, 1473 women (0.4%) had early-onset preeclampsia. Of these, 593 women (40.3%) had no record of another pregnancy (including 1 woman who had died); 93 women (6.3%) had a pregnancy loss at <20 weeks gestation; 10 women (0.7%) had a subsequent multifetal pregnancy, and 19 women (1.3%) had a record for a nonconsecutive pregnancy (parity, ≥2), and were excluded from further analysis ( Figure 1 ). Thus, the study population comprised the remaining 758 women who had a nulliparous pregnancy with early-onset preeclampsia and a subsequent consecutive singleton pregnancy at ≥20 weeks gestation.

At the index birth and compared with nulliparous women without preeclampsia, women with early-onset preeclampsia were older and had higher rates of chronic hypertension, autoimmune diseases, renal disease, morbid obesity, and use of ART, but lower rates of Asian ethnicity ( Table 1 ). At the index birth, 2.5% of women with early-onset preeclampsia delivered at 20 0 –23 6 weeks gestation; 12.8% delivered at 24 0 –27 6 weeks gestation, and 84.7% delivered at 28 0 –33 6 weeks gestation. The interpregnancy interval ranged from 0.7–10.4 years (mean±SD: 2.8±1.5 years).

| Pregnancy characteristics | Early-onset preeclampsia (n=758), n (%) | No preeclampsia a (n=345,447), % | Relative risk (95% confidence interval) b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, y | |||

| <25 | 116 (15.3) | 27.1 | 0.66 (0.53–0.83) |

| 25–29 | 201 (26.5) | 31.1 | Reference |

| 30–34 | 252 (33.3) | 28.4 | 1.37 (1.14–1.66) |

| ≥35 | 189 (24.9) | 13.4 | 2.19 (1.80–2.68) |

| Chronic hypertension | 60 (7.9) | 0.7 | 12.5 (9.57–16.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 44 (5.8) | 5.5 | 1.05 (0.78–1.43) |

| Morbid obesity | 35 (4.6) | 1.5 | 3.30 (2.35–4.64) |

| Autoimmune disease | 16 (2.1) | 0.3 | 6.83 (4.15–11.3) |

| Renal disease | 16 (2.1) | 0.3 | 6.72 (4.08–11.1) |

| Artificial reproductive technology | 52 (6.9) | 3.7 | 1.90 (1.44–2.52) |

| Smoking | 72 (9.5) | 11.6 | 0.80 (0.63–1.02) |

| Asian ethnicity | 73 (9.6) | 15.1 | 0.60 (0.47–0.77) |

| Gestational age, wk | |||

| 20–23 | 19 (2.5) | 0.3 | N/A c |

| 24–27 | 97 (12.8) | 0.3 | N/A c |

| 28–33 | 642 (84.7) | 1.1 | N/A c |

| ≥34 | 0 | 98.3 | N/A c |

| Planned deliveries | |||

| Prelabor cesarean | 636 (83.9) | 9.5 | 8.79 (7.91–9.77) |

| Labor induction | 95 (12.5) | 28.4 | 0.44 (0.36–0.55) |

| Mode of delivery | |||

| Cesarean | 675 (89.1) | 28.2 | 3.15 (2.84–3.50) |

| Vaginal birth | 83 (10.9) | 71.8 | Reference |

| Perinatal death | 87 (11.5) | 0.9 | 12.7 (10.2–15.9) |

a Nulliparae with singleton pregnancies and no preeclampsia ( Figure 1 )

b Relative risk of index birth characteristics and outcomes for women with early-onset preeclampsia compared with those without preeclampsia

c Not applicable because the gestational age was part of index case eligibility.

Women with early-onset preeclampsia in the index pregnancy had a lower rate of subsequent pregnancy: 59.7% vs 67.7% for women without preeclampsia. There was no difference in the subsequent pregnancy rate between women with the index birth at <28 weeks gestation and at 28–33 weeks gestation (60% for both subgroups). Women whose index pregnancy resulted in a perinatal death had a subsequent pregnancy rate of 73%; women whose child survived had a subsequent pregnancy rate of 58%.

Of the 758 women with a subsequent singleton birth, 256 (33.8%) had preeclampsia in the next pregnancy, which includes 57 women (7.5%) with recurrent early-onset preeclampsia. Recurrence of preeclampsia at <34 weeks gestation in the subsequent pregnancy was not significantly different when the index birth was <28 weeks compared with an index birth at 28–33 weeks gestation ( Table 2 ). Of the 116 women with an index birth at <28 weeks gestation, 4 (3.4%) had recurrent preeclampsia at <28 weeks in the next pregnancy. The overall rate of perinatal death fell markedly from 11.5% in the index pregnancy to 1.7% in the subsequent pregnancy (RR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.08–0.27). However, this was still almost twice the 0.9% rate among nulliparous women who did not have preeclampsia ( Table 1 ).

| Subsequent birth outcomes | Index birth gestation, wk | Relative risk (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 0 –27 6 (n=116), n (%) | 28 0 –33 6 (n=642), n (%) | ||

| Any preeclampsia | 43 (37.1) | 213 (33.2) | 1.12 (0.86–1.45) |

| Early-onset preeclampsia at <34 wk | 13 (11.2) | 44 (6.9) | 1.64 (0.91–2.94) |

| Preterm birth at <37 wk | 45 (38.8) | 184 (28.7) | 1.35 (1.04–1.75) |

| Maternal complications | |||

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 7 (6.0) | 31 (4.8) | 1.25 (0.56–2.77) |

| Severe morbidity | 2 (1.7) | 24 (3.7) | 0.46 (0.11–1.93) |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 9 (7.8) | 23 (3.6) | 2.17 (1.03–4.56) |

| Length of stay ≥7 d | 38 (32.8) | 166 (25.9) | 1.27 (0.95–1.70) |

| Perinatal death | 5 (4.3) | 8 (1.2) | 3.46 (1.15–10.39) |

| Infant outcomes among live births | [n=111] | [n=635] | |

| Small-for-gestational age <10th percentile | 20 (18.0) | 102 a (16.1) | 1.12 (0.73–1.73) |

| 5-Minute Apgar score <7 | 4 (3.6) | 12 a (1.9) | 1.91 (0.63–5.81) |

| Severe morbidity | 19 (17.1) | 95 (15.0) | 1.14 (0.73–1.79) |

a Missing data: In 2 records, the size at birth was missing; in 1 record, the Apgar score at 5 minutes was missing.

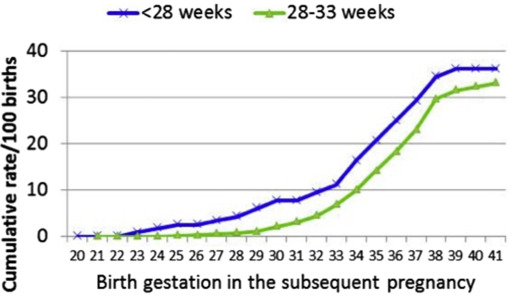

When stratified by gestational age of the index birth, for women with preeclampsia at <28 weeks, the final cumulative rate for any preeclampsia in the subsequent pregnancy was 37.1% ( Figure 2 ). Cumulative preeclampsia rates by week for women with index preeclampsia at 28–33 weeks gestation were parallel but lower at every gestation from 23 weeks, to a total of 33.2%. For both groups, the cumulative rate of recurrent preeclampsia rose most steeply between 32 and 38 weeks gestation. There was no evidence that the risk of recurrence differed if the index pregnancy had resulted in a perinatal death (RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.57–2.29) or if the mother was aged ≥35 years at the time of the index pregnancy (RR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.91–1.41). However, women with chronic hypertension did have a higher recurrence rate (50% vs 32%: RR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.17–2.03).

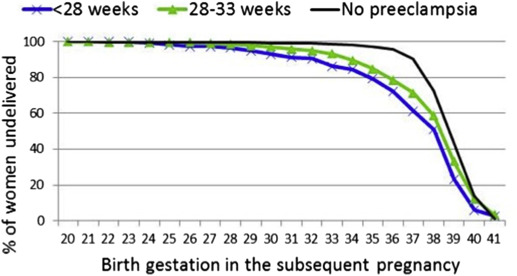

Not all women who delivered preterm in the subsequent pregnancy had recurrent preeclampsia. Figure 3 shows that the proportion of women who remained undelivered at each gestational age in the subsequent pregnancy was lower for index preeclampsia at <28 weeks than those with index preeclampsia at 28–33 weeks, and both were markedly lower compared with women with no history of preeclampsia. Most women (717; 94.6%) progressed to a later gestational age in their subsequent pregnancy. The median overall increase in gestational age at delivery was 6 weeks (interquartile range, 4–8); among the women with recurrent preeclampsia, the median increase in gestation in the subsequent pregnancy was 5 weeks (interquartile range, 2–7). There were 27 women (3.6%) who delivered <34 weeks gestation in their subsequent pregnancy, but who did not have a diagnosis of preeclampsia recorded. Although the reason for the preterm birth is not specified, these pregnancies were complicated by ≥1 the following events: stillbirth, growth restriction, placental abruption, placenta previa, preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes, renal transplant complications, chronic hypertension with renal disease, pulmonary embolism, and unspecified fetal problems.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree