41 Dysmenorrhea: Painful Menstruation Robert L. Barbieri For clinical purposes, dysmenorrhea, or painful menstruation, is divided into two major categories: primary and secondary. Primary dysmenorrhea is the presence of recurrent, crampy pelvic pain in the lower abdomen that occurs just before and/or during menstruation in the absence of suspected or proven pelvic pathology. Secondary dysmenorrhea is painful menstruation in the presence of a disease that causes the recurrent, cyclic pain symptoms, such as endometriosis, adenomyosis, or uterine leiomyomata. The diagnosis of primary dysmenorrhea is made in women with painful menstruation who do not have evidence of pelvic pathology such as endometriosis, adenomyosis, or uterine leiomyomata. In women with severe dysmenorrhea, imaging studies such as sonography may be helpful in detecting major pelvic pathology such as uterine leiomyomata, adenomyosis, or ovarian endometriosis. In women with severe dysmenorrhea who do not respond to standard treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and/or estrogen-progestin contraceptives, laparoscopy may be indicated to diagnose and treat endometriosis. The average age of onset of menses is 12 years and 13 years of age in African-American and Caucasian girls, respectively. In the first 2 years after menarche, about 50% of menstrual cycles are anovulatory. Eventually, for most adolescents, ovulation occurs monthly and menstrual cycle length stabilizes between 24 and 35 days. Painful menstruation is most likely to occur in association with an ovulatory menstrual cycle (Table 41.1). In a population-based sample of 25% of the 19-year-old women living in Gothenburg, Sweden, 72% of subjects reported dysmenorrhea, of which 15% reported that menstruation associated pelvic pain limited their ability to go to school, or to work effectively. In a study of 1546 Canadian women ≥18 years, 60% reported dysmenorrhea and 17% reported that the painful menstruation adversely impacted their school or work performance.

Definitions

Diagnosis

Prevalence and Epidemiology

| Years between first menses and onset of dysmenorrhea | Percentage of adolescents |

| Within 1 year | 38% |

| 1–2 years | 21% |

| 2–3 years | 20% |

| 3–4 years | 10% |

| 4–5 years | 8% |

| 5–6 years | 3% |

Source: Adapted from Andersch B, Milson I An epidemiologic study of young women with dysmenorrhea Am J Obstet Gynecol 1982;144:655–660.

Etiology

Dysmenorrhea is caused by frequent and prolonged uterine contractions, where the uterine pressure is greater than mean arterial pressure, resulting in relative ischemia and triggering of pain nerve fbers in the uterus. From one perspective, dysmenorrhea represents uterine “angina.” Pain nerve fbers in the uterus may also be sensitized or triggered by chemicals secreted by the sloughing endometrium, including prostaglandins and cytokines.

The biochemical sequence that results in frequent and prolonged uterine contractions includes the following. 1) During the menstrual cycle, the sequential stimulation of the endometrium by estradiol during the ovarian follicular phase (endometrial proliferative phase) followed by estradiol plus progesterone during the ovarian luteal phase (endometrial secretory phase) produces an increase of endometrial stores of arachidonic acid, a precursor to prostaglandin production. 2) Just before the onset of menses and during menses, the arachidonic acid stores are converted to prostaglandin F2a, prostaglandin E2 and leukotrienes, which induce uterine contractions. In women with dysmenorrhea, uterine pressures can reach 180 mmHg with resting pressures as great as 80 mmHg. In addition the uterine contractions can be prolonged. 3) Frequent and prolonged uterine contractions that decrease blood flow to the uterus cause uterine ischemia and trigger pain nerve fbers. During uterine ischemia, anaerobic metabolites can accumulate in the uterus and stimulate small type-C pain neurons. From an evolutionary point of view, forceful uterine myometrial contractions during menstruation is probably a physiological adaptation that results in the constriction of uterine blood vessels and limits the magnitude of menstrual blood loss.

Evidence that uterine and endometrial prostaglandins play a central role in causing dysmenorrhea includes the reports that endometrial concentrations of prostaglandins E2 and F2 α correlate with the severity of the dysmenorrhea, that cyclooxygenase inhibitors decrease menstrual fluid prostaglandin levels and reported menstrual pain, and that painful uterine contractions can be caused by administering prostaglandins to pregnant women.

In women with primary dysmenorrhea and increased prostaglandin E2 and F2 a production, the large and small bowel may be hypersensitive to mechanical stimuli. In some women, pain from the bowel may contribute to the visceral pain of dysmenorrhea.

History

Historical features that may be helpful to assess include:

- age of menarche

- date of onset of last two menses

- relationship between onset of symptoms and number of days of symptoms, first and last day of menstrual fow

- location and severity of symptoms

- presence of associated symptoms such as nausea, diarrhea, and back pain

- efficacy of NSAIDs in treating symptoms

In addition to abdominal and pelvic pain, many women with dysmenorrhea report, nausea, diarrhea, and back pain.

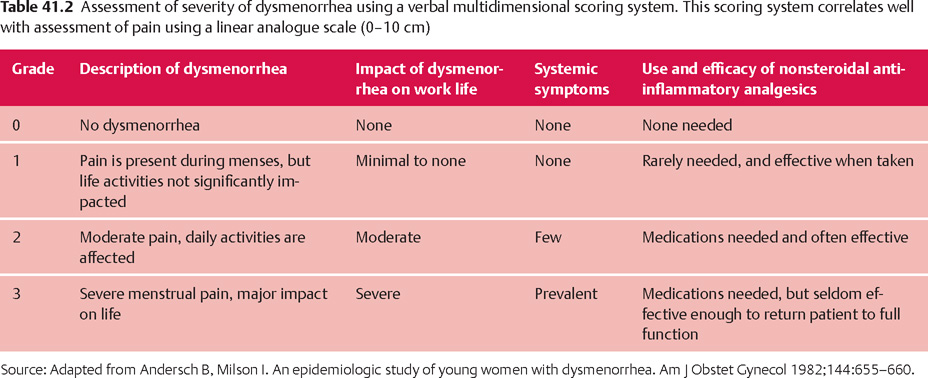

For women with dysmenorrhea, the history can be focused on attempting to determine if a primary or secondary form of the disorder is present. The more severe the symptoms and the greater their functional impact, the more likely that a secondary form of the disorder is present. Women with severe dysmenorrhea who have a negligible response to NSAIDs are also at increased risk for having pelvic pathology that is causing the pain. Table 41.2 provides a simple approach for assigning women with dysmenorrhea to one of three grades of severity. Women with dysmenorrhea in grade 3 should be suspected of having secondary dysmenorrhea.

Physical Examination and Laboratory Studies

Women with primary dysmenorrhea have a normal pelvic exam. For young, nonsexually active adolescents with mild dysmenorrhea, the pelvic exam can be deferred. Women with secondary dysmenorrhea caused by endometriosis, adenomyosis, and uterine leiomyomata may also have a normal pelvic exam. In many cases, women with uterine leiomyomata have an enlarged, irregularly shaped, multilobular uterus. Women with adenomyosis may have a uterus that is at the upper limits of normal in size and tender on palpation. Women with endometriosis may have a number of physical findings including: 1) cervical stenosis, as demonstrated by a cervical os diameter of less than 4 mm; 2) nodular or indurated uterosacral ligaments due to endometriosis lesions on those ligaments; 3) displacement of the cervix to a lateral vaginal fornix due to asymmetric shortening of one uterosacral ligament, cardinal ligament complex (Fig. 41.1). Some women with endometriosis afecting the ovary have enlarged adnexa on pelvic exam. Endometriosis commonly produces inflammation that causes the pelvic tissues to become indurated and “woody,” with fixed and nonmobile pelvic structures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree