Drainage and Packing of a Nasal Septal Hematoma

Colette C. Mull

Mark A. Ginsburg

Introduction

A nasal septal hematoma forms when blood collects in the potential space between the cartilage of the nasal septum and its overlying mucoperichondrium. The presence of a hematoma impairs blood flow into the septal cartilage and can thereby lead to cartilage necrosis. Blunt trauma is by far the most common cause of a septal hematoma (1,2,3,4). Septal hematoma may also present as a complication of septoplasty or recurrent rhinitis or sinusitis (5). In children, the most common causes of nasal trauma are unintentional household injuries and sports injuries (4). Other etiologies in older children and adolescents include motor vehicle crashes and fights (1,6). Published case reports have described the occurrence of nasal septal hematoma in infant victims of nonaccidental injury (4,6,7,8). Provided no reaccumulation of blood occurs, drainage and packing of a septal hematoma is a curative procedure.

Drainage and packing of a septal hematoma is moderately complex and requires good technical skill. It fulfills the criteria for minor surgery and therefore should be performed by physicians only. The difficulty of treating a septal hematoma in a pediatric patient is usually inversely proportional to the age of the child. For a very young or extremely fearful child, this procedure is often most easily done in the operating room. However, if timely treatment by an otolaryngologist is unavailable, drainage and packing of a septal hematoma in such patients can be performed in an emergency department (ED) setting with procedural sedation (Chapter 33). For a cooperative older child or adolescent, the procedure normally can be successfully accomplished using local anesthesia alone.

Anatomy and Physiology

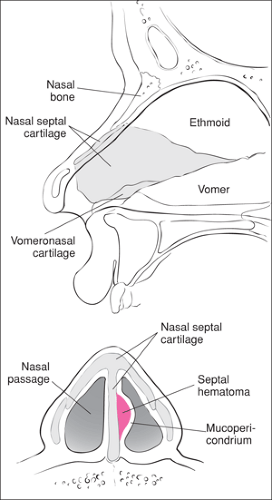

The nasal septum is formed by the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone, the vomer bone, and the quadrangular cartilage (9). The thin septal cartilaginous plate supports the nasal tip and is lined by a closely adherent perichondrium and its overlying mucosa (Fig. 58.1) (9). The rich vascular network within the mucoperichondrium constitutes the blood supply to the nasal septal cartilage. Because of a relative lack of bony support, the nasal septum is often damaged as it bends and buckles under pressure. Forces generated by nasal trauma cause a separation of the mucoperichondrium from the cartilage; a septal hematoma is formed as torn submucosal blood vessels fill the potential space with blood (7). Without timely incision and drainage, the hematoma exerts increasing pressure on septal vasculature. With no alternative blood supply to the area, this pressure can impede perfusion of the nasal cartilage, potentially resulting in cartilage necrosis, cartilage resorption, septal abscess, saddle-nose deformity of the nose, and/or varying degrees of nasal obstruction (2,3,5,7,10). An untreated septal abscess can progress by direct extension and/or by hematogenous spread to involve intracranial structures (5). With or without disruption of the integrity of the septum (e.g., septal fracture), the patient may present with bilateral hematomas, an entity that carries a greater risk for permanent complications (3,5,7). Drainage of a nasal septal hematoma improves blood flow to the area but may not reverse antecedent cartilage destruction.

Indications

Any child who sustains trauma to the midface should be carefully examined to exclude the presence of a septal hematoma

or other injuries to the nose. Because of the potential for adverse long-term sequelae with such injuries, this aspect of the overall physical examination must not be overlooked. A septal hematoma will appear as a discolored (usually red, dark blue, or purple), fluctuant bulge. It has a doughy consistency and is tender to palpation. As mentioned, a septal hematoma may occur on one or both sides of the nasal septum (5,10,11,12). A septal hematoma should be drained as soon as is possible but certainly within 48 hours of its onset to avert the potential complication of irreversible septal necrosis that occurs by day 3 to 4 (13).

or other injuries to the nose. Because of the potential for adverse long-term sequelae with such injuries, this aspect of the overall physical examination must not be overlooked. A septal hematoma will appear as a discolored (usually red, dark blue, or purple), fluctuant bulge. It has a doughy consistency and is tender to palpation. As mentioned, a septal hematoma may occur on one or both sides of the nasal septum (5,10,11,12). A septal hematoma should be drained as soon as is possible but certainly within 48 hours of its onset to avert the potential complication of irreversible septal necrosis that occurs by day 3 to 4 (13).

Because a septal hematoma in a young or extremely fearful child is most easily treated under general anesthesia, these cases are usually managed in the operating room. If drainage is attempted in the ED using procedural sedation, great care must be taken to prevent any movement of the patient during the procedure so that inadvertent perforation of the septum does not occur. Although deviation of the nasal bone and/or nasal septum is not necessarily a contraindication for drainage, it does increase the complexity of the procedure and merits otolaryngology consultation (14,15,16).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree