More recently, Jordan et al.15 expanded on this classification system to include both arthroscopic and clinical findings in order to more completely describe discoid meniscus type and therefore provide more insight into appropriate treatment.1,2,14,15 This classification system stratifies discoid lateral meniscus pathology into stable and unstable categories. Stable variants have normal anterior and posterior tibial attachments, irrespective of the presence of a Wrisberg ligament, and therefore have normal mobility.14 These types include the Watanabe type I (complete) and type II (incomplete) meniscal variants. The unstable types are defined as those without a posterior meniscotibial ligament, that is, the Watanabe type III, or Wrisberg, variant. These tend to be hypermobile given their anomalous attachments. The unstable category is then subdivided into unstable with a discoid shape and unstable with normal shape. Each of these—stable, unstable discoid, and unstable normal—are then stratified based on whether they are torn or not torn and whether they are symptomatic or asymptomatic.2,19

Evaluation of a patient with suspected discoid meniscus involves detailed history taking, clinical examination, and imaging. As previously stated, stable variants of discoid meniscus tend to present in association with a tear, whereas uninjured, stable discoid menisci are usually detected only incidentally during imaging or arthroscopy for another condition. The Wrisberg variant, on the other hand, may present as snapping knee, and symptoms are not contingent on meniscal injury. Consequently, presentation may be highly variable and dependent on meniscal type, stability, and presence or absence of a tear.1 Of note, the classic complaint of snapping knee can occur in a formerly stable type I or II discoid meniscus if a tear occurs such that the posterior meniscotibial attachment is avulsed, causing a Wrisberg-type pathology.4 An unstable discoid meniscus that presents with snapping is more likely to cause pain and discomfort with activity in older children (8 to 10 years of age) and is highly unlikely to cause uncomfortable symptoms or pain in younger patients (age 3 to 4 years).3

Symptoms that occur in the setting of a torn, stable discoid meniscus are similar to those of a tear in a normal-shaped meniscus and include pain, swelling, catching, locking, a sense of “giving out,” and decreased range of motion. However, in contrast to tears of normal menisci, discoid tears differ in that they may not always present in the setting of acute trauma and may instead have a more subacute course without a known inciting event.1,4 Snapping on terminal extension, or symptoms of a meniscal tear without known trauma, particularly in younger children, should increase suspicion for discoid meniscal pathology.

On examination, physical findings may include block to or pain with terminal motion, particularly extension; flexed stance during ambulation (to avoid uncomfortable snapping with extension); and a prominent bulge at the anterolateral joint line with maximal flexion.2 Unstable discoid menisci may present earlier, as a tear is not required to elicit symptoms, and may be associated with a palpable, visible, or audible popping/snapping during extension as the meniscus reduces into its normal anatomic position.1 Physical examination in a patient with a torn discoid meniscus will reveal similar findings to those with torn normal menisci. On top of those findings associated with discoid pathology, examination may reveal knee effusion, joint line tenderness, loss of range of motion, and positive McMurray and/or Apley maneuvers.1 A positive McMurray is particularly rare to find in young children, and so absence of positive provocative maneuvers to detect meniscal pathology should not necessarily decrease suspicion in these patients. Imaging remains critical to the diagnosis given the variability in presentation and in examination findings. Estimates of clinical examination accuracy have ranged from 29% to 93% when compared to arthroscopic findings and are likely dependent on the experience of the practitioner.4,16–18 Nonetheless, if discoid meniscus is suspected based on symptoms and examination, a detailed examination and possibly imaging of the contralateral, asymptomatic knee may be indicated, given the high rate of bilaterality in this condition.3

Due to the variability of clinical examination, imaging is an essential component in the diagnosis of discoid meniscus. Imaging generally begins with plain radiographs, although these are frequently normal, particularly in younger children. However, when typical findings are present, they may greatly aid in arriving at the correct diagnosis. Four views, namely, anteroposterior, lateral, sunrise, and tunnel views, are generally recommended. Findings on plain radiographs vary but may include a widened lateral joint line (secondary to widened lateral meniscus), cupping of the lateral tibial plateau, squaring or flattening of the lateral femoral condyle, calcification of the lateral meniscus, tibial eminence hypoplasia, and fibular head elevation.1,2,4 Other musculoskeletal abnormalities that have been associated with discoid meniscus include fibular muscle defects, abnormally contoured lateral malleolus, and enlarged inferior lateral geniculate artery.4 Specifically of concern for the pediatric sports surgeon is the association between discoid meniscus and osteochondral pathology of the lateral femoral condyle.4 If present, these findings should increase suspicion for discoid meniscal pathology.

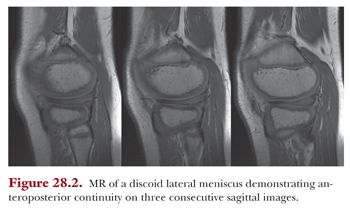

After plain radiographs, and particularly if initial radiographic findings are concerning for discoid meniscus, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is indicated. Multiple findings on MR may suggest a diagnosis of discoid meniscus. Presence of any one of three criteria is consistent with a diagnosis of discoid meniscus. One criterion is continuity of anterior and posterior meniscal horns on at least three consecutive sagittal images (Fig. 28.2). Given that the normal meniscus is 12 mm in diameter and MR images are spaced by a standard 5 mm, this appearance of anteroposterior continuity should only be present on a maximum of two slices. When present on three of more, it is known as a bow tie sign and is indicative of discoid pathology. Another diagnostic criterion is a transverse meniscal diameter of greater than 15 mm, and the last is a transverse meniscal diameter that is greater than 20% of the total tibial width on any axial image (Fig. 28.3). The ratio of the sum of the width of both lateral meniscal horns to the maximal meniscal diameter (all on sagittal view) of greater than 75% has also been considered by some to be diagnostic.4 Other MR evidence of discoid meniscus may include an abnormally thick, flat meniscus on any view, possibly demonstrating a thickened, extruded meniscus spanning the entire lateral tibial plateau on coronal images (Fig. 28.4) and increased thickness of the anterior horn, the posterior horn, or the entire meniscus.2 MR imaging is also critical in evaluation of meniscal tears (Fig. 28.5), intrasubstance pathology, and presence of concomitant osteochondritis dissecans.4