Diagnostic Laryngoscopic Procedures

Erin D. Phrampus

Robert F. Yellon

Introduction

The larynx, hypopharynx, and posterior nasopharynx cannot be adequately visualized by simple examination, and results obtained on plain radiograph may be incomplete or misleading. Special equipment and techniques are therefore necessary to gain accurate information regarding the anatomy and function of these structures. Children who present with complaints such as recurrent or persistent stridor, chronic hoarseness, or a suspected airway foreign body (without respiratory distress) may be candidates for these procedures. A preliminary examination in the emergency department (ED), office, or other outpatient setting can aid the physician in determining the appropriate management, disposition, and follow-up studies for the patient. Thus diagnostic laryngoscopy is a valuable skill for emergency physicians, pediatricians, and family physicians.

The upper airway can be divided anatomically into the extrathoracic and intrathoracic regions. The extrathoracic region can further be divided into the supraglottic area (nasopharynx, epiglottis, larynx, aryepiglottic folds, and false vocal cords) and the glottic/subglottic area (extending from the vocal cords to the extrathoracic segment of the trachea). With indirect laryngoscopy, the glottis, vocal cords, and supraglottic structures are visualized using an angled mirror placed above the patient’s larynx. Direct laryngoscopy involves visualization of the larynx through an eyepiece using an angled telescope or flexible fiberoptic laryngoscope. Advances in fiberoptic technology have led to the development of progressively smaller devices that are appropriate for pediatric use and have excellent image resolution. The flexible fiberoptic laryngoscope can also be used to examine the nasal cavity.

These techniques can be used for most stable pediatric patients. Infants and younger children are not developmentally capable of cooperating with indirect laryngoscopic procedures. Older children and adolescents may be able to tolerate an indirect laryngoscopic examination if the procedure is thoroughly explained and carefully performed. The procedures described in this chapter are intended for the outpatient examination of pediatric patients who are generally well. If there are signs of respiratory distress, an otolaryngologist should perform the procedure, preferably in the operating room. Even with the well child, airway equipment should be readily available when these procedures are performed, as inadvertent contact with the larynx in rare instances can precipitate laryngospasm.

Anatomy and Physiology

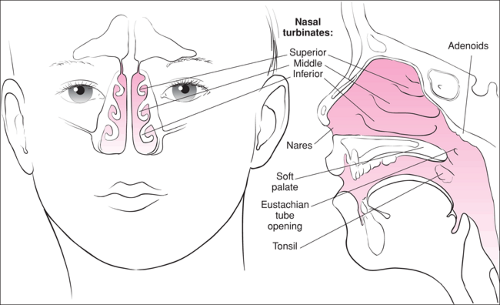

A detailed discussion of distinguishing features of pediatric airway anatomy can be found in Chapter 16. The upper airway starts with the nasal cavity and continues with the nasopharynx and oropharynx to the larynx and the extrathoracic segment of the trachea. The structures of greatest interest during diagnostic laryngoscopy are the posterior nasopharynx and adenoids, the hypopharynx, and the vocal cords and supraglottic region (Fig. 61.1).

The upper airways are protected from infection by a system of lymphatic tissue known as the Waldeyer ring, which comprises the lymphoid tissue in the nasopharynx (adenoid tissue), the lymphatic tissue at the base of the tongue (lingual tonsils), and the two palatine tonsils. However, this lymphatic system can also become a site of acute or chronic infection. Adenoidal hypertrophy can occur with or without infection, and extensive hypertrophy can result in blockage of the nasal passages. Enlarged adenoids can obstruct the eustachian tube orifice, leading to otitis media. Chronic upper airway obstruction often presents with evidence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. In severe cases, these children may present with pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale (1).

Foreign bodies can become embedded in the hypopharynx and supraglottic areas, and these may be undetectable on routine physical examination of the oropharynx. In addition, plain radiographs may not identify certain types of items, including tiny fish bones, wooden splinters, and organic materials such as sunflower seeds and nuts. Indirect or direct laryngoscopy may be the only means of detecting such a foreign body (2).

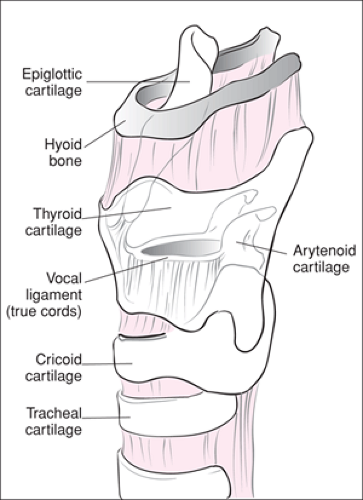

The larynx is part of the anterior hypopharynx (Fig. 61.2). In newborns, the larynx is at the level of C3–C4 and gradually descends to the level of C6–C7 around adolescence. The hyoid bone forms the upper limit of the larynx, which is divided into the supraglottic, glottic, and subglottic regions. The supraglottic region encompasses the area above the vocal cords and includes the epiglottis, arytenoids, aryepiglottic folds, and the false vocal cords. The glottic region includes the vocal cords and the subglottic structures extending 1 cm below the vocal folds in the upper cervical trachea. The true vocal cords are paired, V-shaped structures with the point facing anteriorly. The vocal cords vibrate to produce the sound of the voice. Abnormalities may result in hoarseness or stridor.

Phonation results from a series of minute changes in the muscular tension exerted on the vocal cords as air is forced out through the glottic opening. The vocal cords vibrate to produce the sound of the voice. In pediatric patients, common causes of hoarseness or stridor include laryngomalacia, vocal cord paralysis or paresis, vocal cord nodules, subglottic hemangioma, and juvenile laryngeal papillomatosis (3,4,5).

Infants with a low-pitched cry who have findings suggestive of a neuromuscular disorder, a congenital anomaly of the mediastinum (e.g., tracheoesophageal fistula, vascular ring), or Arnold Chiari malformation should be suspected of having unilateral or bilateral vocal cord paralysis. The large, floppy epiglottis of an infant often will fall back and forth over the glottis during respiration, giving the clinician an intermittent view of the vocal cords on laryngoscopy.

Infants with a low-pitched cry who have findings suggestive of a neuromuscular disorder, a congenital anomaly of the mediastinum (e.g., tracheoesophageal fistula, vascular ring), or Arnold Chiari malformation should be suspected of having unilateral or bilateral vocal cord paralysis. The large, floppy epiglottis of an infant often will fall back and forth over the glottis during respiration, giving the clinician an intermittent view of the vocal cords on laryngoscopy.

Indications

A variety of presenting complaints may serve as indications for performing indirect or direct laryngoscopic procedures (Table 61.1). In general, any child with persistent symptoms believed to involve the nasopharynx, supraglottic region, or vocal cords that cannot be explained based on findings from a routine physical examination may be a candidate for a diagnostic laryngoscopic procedure. The safety of these techniques when performed properly has been demonstrated in both the inpatient and outpatient settings (6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16).

Complaints such as voice changes, chronic stridor or hoarseness, an unusual cry, and persistent odynophagia should generally prompt the physician to examine the vocal cords and supraglottic region using indirect or direct laryngoscopy. Abnormalities of vocal cord function or the presence of a penetrating foreign body warrant evaluation by an otolaryngologist. One relatively common cause of stridor in infancy is laryngomalacia. It accounts for 65% to 75% of all cases of stridor and is caused by the collapse of the supraglottic structures during respiration. It is a self-limited condition that typically resolves without therapy by 12 to 18 months of age. However, in about 5% of affected children the upper airway obstruction is severe enough to cause apnea or failure to thrive. The etiology of laryngomalacia is unknown, and some investigators believe it represents a form of laryngeal “hypotonia,” while others believe that increased flexibility of the cartilage is the cause. Infants with laryngomalacia typically have inspiratory stridor that is more pronounced when supine and decreases when prone. Abnormalities of swallowing may occur in up to 50% of patients (17). Laryngoscopy will reveal the epiglottis and the arytenoids collapsing into the glottis with inspiration during spontaneous ventilation (18). Notably, children exposed to hot fumes or a house fire may have no stridor or voice change initially, despite thermal injury. In such children, a laryngoscopic examination that shows edema or carbonaceous deposits requires that the patients be subject to close observation and often early endotracheal intubation.

TABLE 61.1 Indications for Diagnostic laryngoscopy | |

|---|---|

|

Children with chronic mouth breathing, snoring respirations, or persistent nasal drainage often require an examination of the nasopharynx with a fiberoptic laryngoscope (19,20,21,22). Obstruction of the nasal cavity in children is commonly caused by adenoidal hypertrophy. The finding of significantly enlarged adenoid tissue, particularly when the orifice of the eustachian tube is occluded, is an indication for referral to an otolaryngologist. Other conditions causing chronic nasal obstruction include nasal polyps, the presence of a foreign body, and encephalocele, which can communicate directly with cerebrospinal fluid (23). Polyps appear as gray, grapelike masses in the nasal cavity and are highly associated with cystic fibrosis. A foreign body not seen on a more limited examination may be visible during an examination of the posterior nasal cavity with a fiberoptic laryngoscope. Care should be taken not to push the object posteriorly, which may result in aspiration.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree