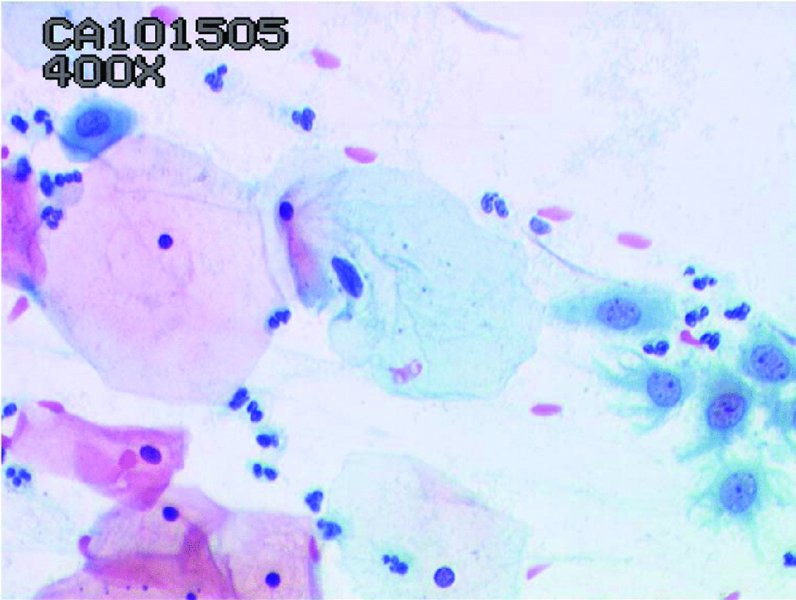

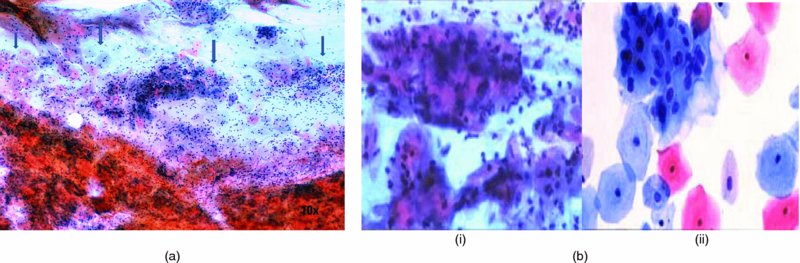

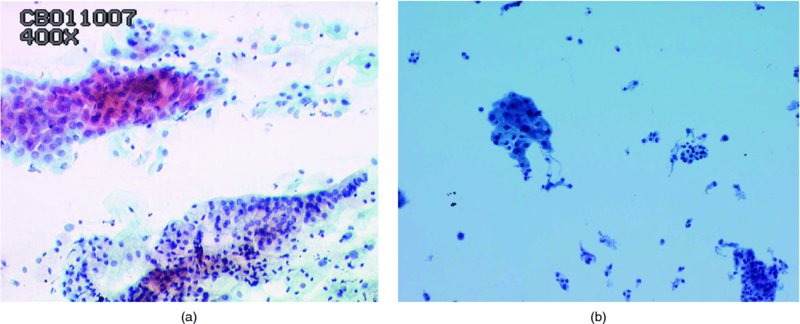

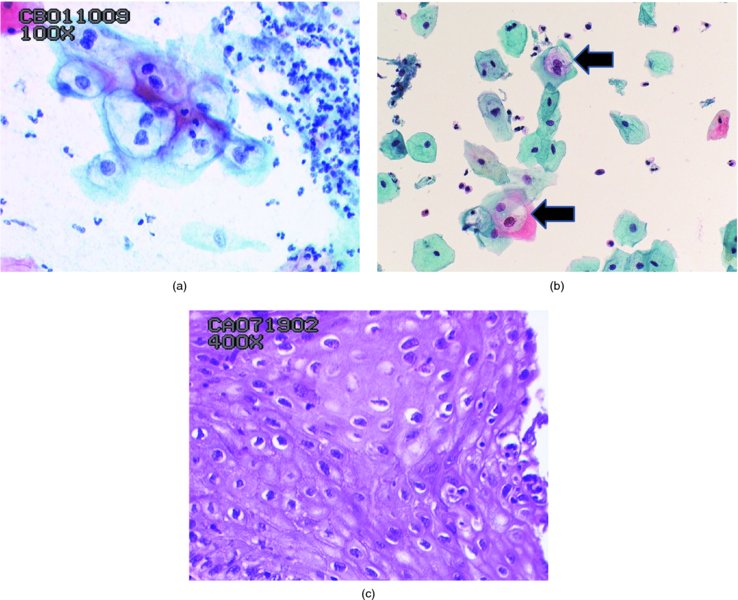

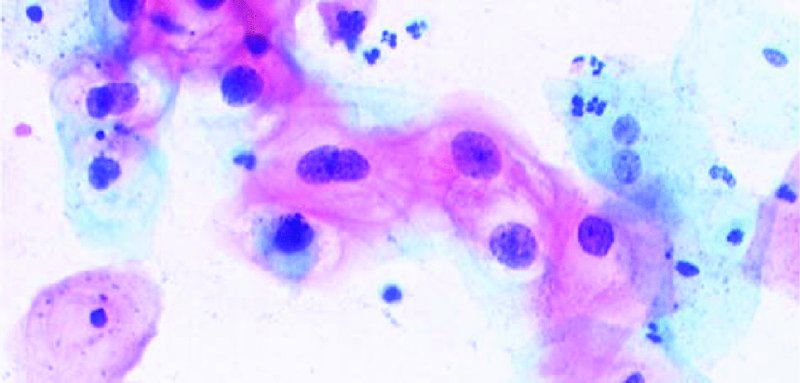

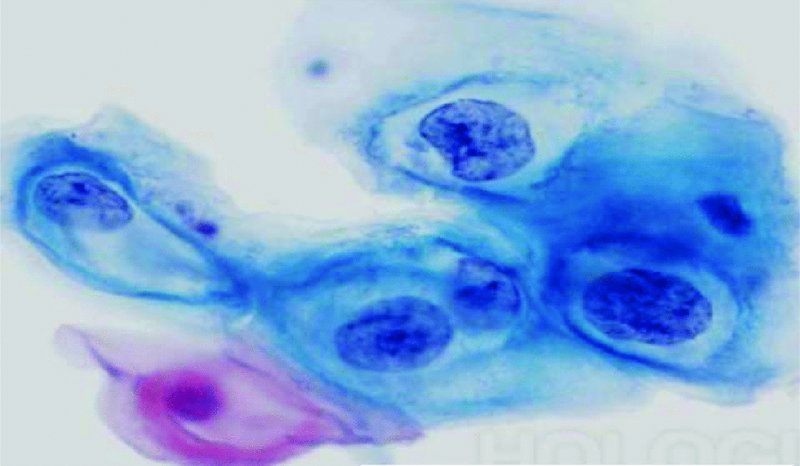

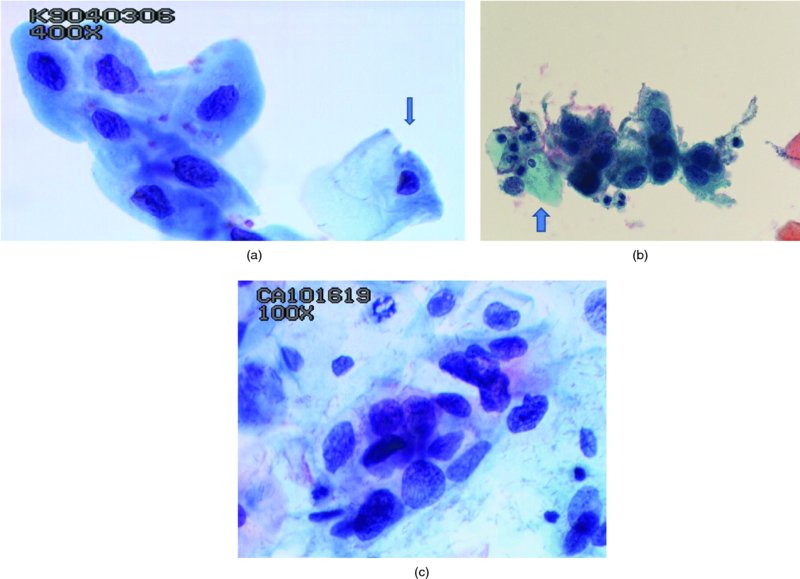

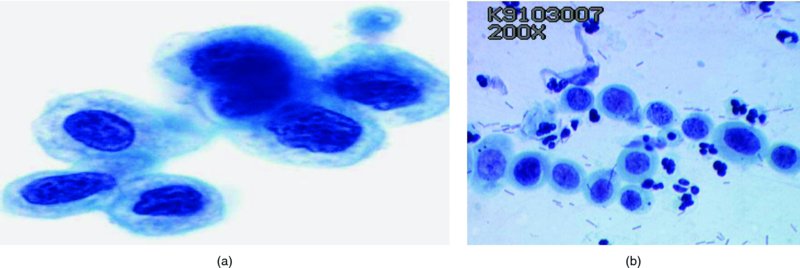

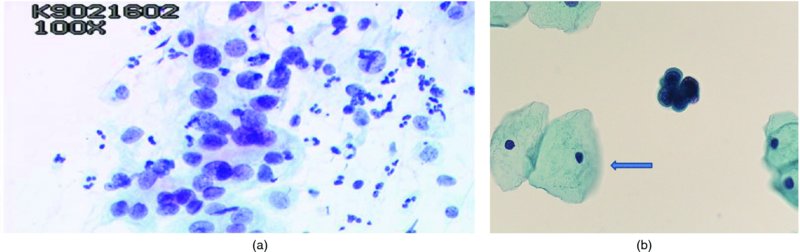

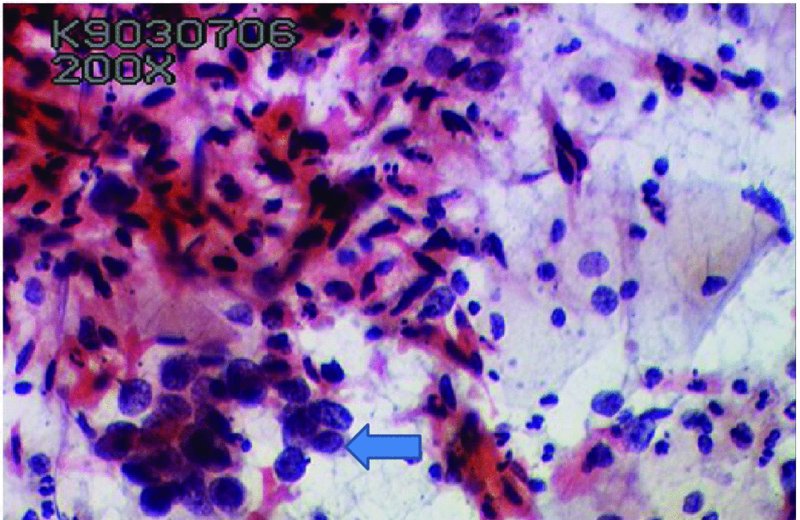

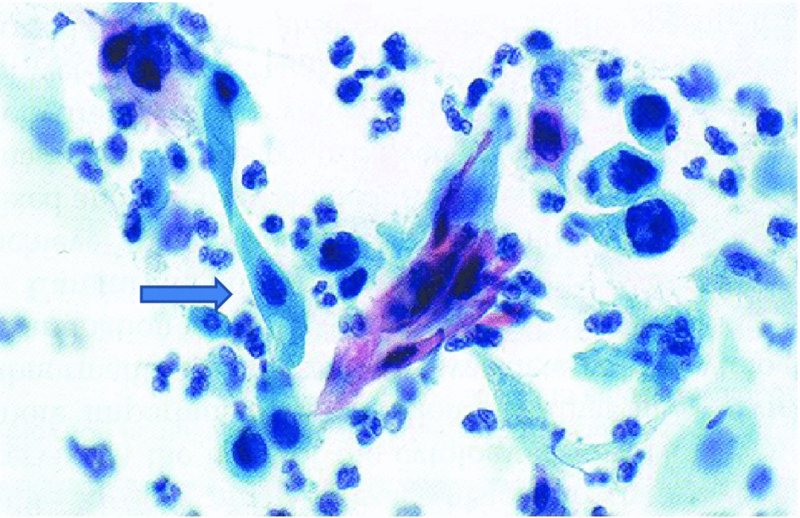

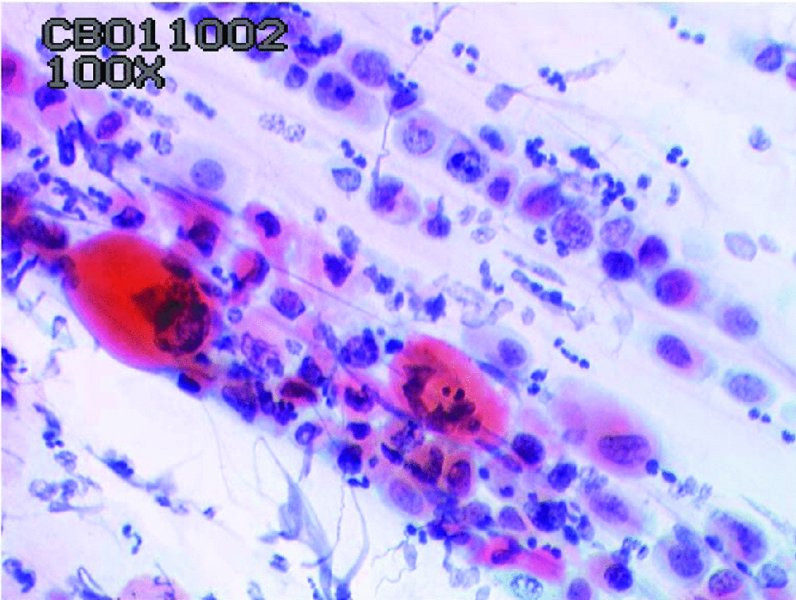

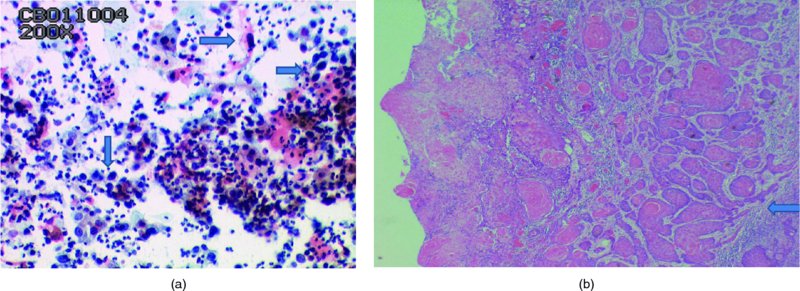

CHAPTER 5 Precancerous cervical cells cause no symptoms and may only be detected by population screening methods. The use of cytology to predict histologic lesions dates back to the 1940s, when it became evident that cervical smears contain atypical cells which display different degrees of cytoplasmic maturation to mirror the histologic lesions. Cervical cytology became the standard screening test for cervical cancer and premalignant cervical lesions with the introduction of the Papanicolaou smear in 1941. The nomenclature for cervical squamous cytology has not changed drastically since Papanicolaou’s first description in 1943. “Dyskaryotic” squamous cells are cells with abnormal nuclear appearances. “Perinuclear cavitation” was described and linked with superficial and intermediate squamous cell dyskaryosis and seen to commonly regress spontaneously. This “cavitation” was later referred to as koilocytosis by Koss et al. in 1956. These changes were then identified as human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cytopathic effects by Meisels and Fortin in 1976 and by Purola and Savia in 1977. For general cytology, Papanicolaou had developed a five-grade system of classifying cells for detecting tumors, using Roman numerals I–V: The same system was applied for cervical cytology but was modified by different users in different countries. The British Society for Clinical Cytology (BSCC) working party in 1986 made attempts to refine Papanicolaou’s work and make the cytologic terminologies more akin to the histologic cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) system. Dyskaryotic nuclei without regard for other cellular features are considered to be separable into mild, moderate, and severe categories, which then predict CIN1, 2, or 3. A borderline grade was introduced that was similar to Papanicolaou grade II and that received “clarification” in the UK by a working party of the National Health Service (NHS) Cervical Screening Programme in 1994. In the USA, the National Cancer Institute devised a system called the “The Bethesda System” (TBS) for reporting cervical/vaginal smears (National Cancer Workshop 1988; Table 5.1). Table 5.1 The Bethesda System classification (2001) for abnormal cells The most important issues addressed in the first National Cancer Workshop in 1988 (and subsequently modified in 1991 and 2001) were: recommending a statement of adequacy; incorporating recommendations by the cytopathologist regarding follow-up; and changing the reporting of cytologic abnormality from the numeric Papanicolaou class system to a descriptive system that incorporates specific terms for non-diagnostic atypia (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS)) and low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSILs and HSILs, respectively). The most recent revision (in 2001) redefined the previously described system by: This system has essentially three categories of findings: The fundamental differences between TBS and the BSCC classification are: The terminology recognizes the frequency of regression and refers to predicted “lesions,” not neoplasia. In use, the new system appears to have seen a major expansion of the inconclusive smear result, namely ASCUS or AGCUS (see section 5.5). However, this is probably more a consequence of the recent frequency of litigation for false-negative assessment in the USA rather than any criticism of the classification. The types of epithelial cell seen in a cervical smear are determined by: Several basic cytologic patterns can be recognized. Under the influence of unopposed estrogen, the squamous epithelium of the cervix thickens and a smear taken mid-cycle, for example, will contain numerous superficial squamous cells. In practice, however, most smears show an intermediate level of maturation, probably reflecting endogenous progestogens or exogenous hormones administered as oral contraceptives. A smear from a normal cervix will contain: This list is routine but not exhaustive. If no dyskaryosis is present, the smear report is normal or negative (Figure 5.1). Figure 5.1 Normal smear stained with liquid-based cytology. Superficial squamous cells are the eosinophilic/orangeophilic mature cells with a small uniform nucleus. An occasional intermediate layer (middle layer) squamous cell is also present. Metaplastic cells are present with cytopoietic processes. Very occasional neutrophils are seen in an otherwise clean background. Figure 5.2 (a) A conventional Papanicolaou smear in which the bulk of the squamous cells (marked by arrows) are obscured by blood and thick mucus. (b) Comparison between a conventional Papanicolaou smear (i), which is difficult to interpret, and the liquid-based cytology smear (ii), which has a clean background and is easy to read. Evaluation of specimen adequacy by the screener is considered by many to be the single most important quality assurance procedure that can be provided by the laboratory. However, there has been much debate in the past regarding characterizing an adequate smear. Definitions of adequate smear that prescribe the number of cells are not practical. The total squamous cellularity is extremely variable. Endocervical and metaplastic squamous cells do not reliably indicate direct endocervical canal sampling. Provided that the smear-taker is confident that the cervix has been fully visualized and a full 360° sweep has been made while taking the smear, the conventional smear is considered adequate if: The introduction of liquid-based cytology (LBC), including the ThinPrep and SurePath methods, has dramatically improved the smear adequacy rates by providing clearer samples to read. Excess blood, mucus, and neutrophilic exudate is washed out and the LBC samples have more uniformly distributed cells. In Figure 5.2b, the conventional smear (Figure 5.2bi) is compared with an LBC-acquired specimen (Figure 5.2bii). Figure 5.3 (a) An atrophic postmenopausal smear with clumps of suprabasal squamous cells in trails. Normal maturation is absent and such cells can mimic dyskaryotic suprabasal cells predicting severe disease. (b) A paucicellular atrophic smear with numerous stripped or isolated parabasal cells whose nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio must be very carefully assessed to avoid missing sometimes high-grade abnormalities. Atrophic smears may present particular difficulties for cytologic assessment, whether postmenopausal or postnatal. The lack of estrogen produces thin epithelia, which yields rafts of cohesive parabasal cells (Figure 5.3a) or trails of “stripped” parabasal nuclei mimicking dyskaryosis (Figure 5.3b). The cellularity of the smear is often low, and the retracted transformation zone may be poorly or not represented. This is the basis for treating such patients briefly with estrogens and retaking a smear to ensure adequacy by increasing the smear yield and decreasing the cytologic difficulties introduced by immature and inflamed cell populations. Figure 5.4 (a) Borderline nuclear changes with koilocytosis showing the typical perinuclear halo with condensed cytoplasmic rim. (b) Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance/borderline nuclear changes smear with prominent koilocytes showing a sharp cytoplasmic halo (marked with arrows) amid intermediate squamous cells. (c) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) section of a cervical biopsy showing a wart virus-associated koilocytic change. The cytologic features of a koilocyte in H&E section are similar to those seen in smears. In the BSCC nomenclature, the category of “borderline nuclear changes” (BNC) appears largely to refer to “HPV-associated nuclear atypia” (Figure 5.4a–c). TBS 1988 created the ASCUS category to identify the subset of squamous atypias that cannot be readily designated as benign or preinvasive. The category was renamed simply as ASCs in the 2001 revision with its further subclassification into ASCUS and ASC-H; “ASCs” cannot rule out HSIL. The more recent approach to incorporate HPV testing for the BNC or ASC category will help in further defining this uncertain category. However, for HPV testing to be effective it is critical that this category does not include cases that are a clear example of inflammatory atypia or reactive atypia. Figure 5.5 Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion/mild dyskaryosis with koilocytosis. Many cells show mildly increased nuclei with a coarse granular chromatin pattern. Occasional cells show perinuclear clearing of the cytoplasm with a hard margin to the vacuole. There are occasional binucleated cells. These are typical koilocytes with low-grade atypia. Figure 5.6 Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL)/mild dyskaryosis with koilocytosis. The cells show typical koilocytosis but in addition have a more coarse chromatin pattern with mildly increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio and an irregular nuclear membrane in keeping with mild dyskaryosis and koilocytosis/LSIL. This pattern is evident when intermediate or superficial squamous cells with nuclear enlargement (usually threefold) and hyperchromasia are seen alongside normal cells (Figure 5.5). The nuclei have a smooth nuclear membrane and small irregularities in nuclear shape and contour. Hyperchromasia is present and may take the form of a finely granular chromatin pattern or uniformly increased nuclear density with opaque or smudged appearance (Figure 5.6). Mimics of LSIL/mild dyskaryosis in-clude trichomonas infections with mild perinuclear halos, postmenopausal nucleomegaly, and non-specific reactive nuclear changes leading to mild superficial nuclear atypia. Figure 5.7 (a) High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL)/moderate dyskaryosis. Nuclear hyperchromasia and enlargement are seen occupying nearly half of the cell. Compare with the cell (marked by an arrow) showing low-grade atypia. (b) Cluster of HISL/moderate dyskaryosis within metaplastic cells, which are seen as cells with large nuclei compared with a single intermediate cell (marked with an arrow). (c) HISL/moderate dyskaryosis. Group of cells with high-grade atypia. The cells have large hyperchromatic nuclei but there is still more than one-third of the cytoplasm visible. Figure 5.8 (a) High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL)/severe dyskaryosis. High-power view of a cluster of cells with severe dyskaryosis. These cells are small with hyperchromatic nuclei which occupy more than two-thirds of the cell. The cells have a coarse chromatin pattern and irregular nuclear membrane. (b) HISL/severe dyskaryosis. Single-file pattern of cells with large hyperchromatic nuclei. The background neutrophil is small in comparison. Figure 5.9 (a) High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL)/severe dyskaryosis. Typical aggregated HISL/severe dyskaryosis composed of a cluster of dyskaryotic parabasal cells along with single scattered cells with similar nuclear features. (b) HISL/severe dyskaryosis. Single-cell HSIL/severe dyskaryosis, which is very often seen in liquid-based cytology samples. These cells are small compared with the background intermediate cells (marked with an arrow). Although these are small cells the nucleus is large and it is occupying almost the entire cell. There is a potential to miss this single-cell dyskaryosis pattern. On cytologic preparations the cells of HSIL/moderate and severe dyskaryosis are characteristically less mature and exhibit a higher nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio than those of LSIL (Figure 5.7a–c). The nuclear enlargement is generally in the same range as LSIL but, because the nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio is increased, the cells appear smaller (Figure 5.8a,b). Hyperchromasia, coarse chromatin, and nuclear membrane irregularities are all more severe than in LSIL (Figure 5.7c). These cells are arranged either as cohesive groups or as single cells (Figure 5.9a,b). Mimics of HSIL/moderate and severe dyskaryosis include: atrophic changes, which are evident by a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio but greater regularity in nuclear contour and absence of coarse chromatin; sampling of the lower uterine segment, in which syncytial groups of the lower uterine segment may be confused with HSIL; and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), which may be difficult to distinguish from HSIL. Figure 5.10 Typical invasive smear with many atypical cells, some of which are spindle-shaped and have an orangeophilic cytoplasm indicative of squamous cells. In the bottom left corner the cells are large atypical with a more round nuclei (marked with an arrow) suggestive of an admixed glandular component of this adenosquamous carcinoma. The principal and most reliable pattern of possible invasion in a cervical smear is the presence of an ulcerative or malignant “diathesis” (Figures 5.10, 5.11). This is the presence of pleomorphic, keratinized, and parabasal squamous cells with often pale, degenerate nuclei, together with inflammatory cell exudate, necrotic (ghost) tumor cells, and fresh blood (Figures 5.12, 5.13a,b). However, comedo-like crypt CIN3 lesions can mimic these appearances in smears. Figure 5.11 Invasive squamous cell carcinoma smear that shows a severely dysplastic squamous cell (arrow) with a spindle cell morphology in a dirty inflammatory background indicative of invasion. Figure 5.12 Invasive squamous cell carcinoma that shows a raft of highly atypical squamous cells together with bizarre orangeophilic cells with a highly irregular cell membrane. Figure 5.13 (a) Tumor diathesis showing severely atypical squamous cells (marked with arrows) admixed with necrosis and inflammatory cells. The inflammatory infiltrate makes it difficult to spot the atypical squamous cells. (b) Hematoxylin and eosin section showing a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma with keratinization within the tumor nests. Towards the deep end of the tumor the nests of atypical squamous cells have an infiltrative edge (marked by an arrow).

Cytology and screening for cervical precancer

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Cytologic classifications

Papanicolaou classification

British Society for Clinical Cytology classification

The Bethesda System

Atypical squamous cells

Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US)

Atypical squamous cells—cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H)

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LGSIL or LSIL)

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL or HSIL)

Squamous cell carcinoma

Atypical glandular cells not otherwise specified (AGC-NOS)

Atypical glandular cells, suspicious for AIS or cancer (AGC-neoplastic)

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS)

5.3 Cytologic reporting

Basic cytologic pattern

Normal cytology

Smear adequacy (Figure 5.2)

Atrophic smears (Figure 5.3)

Borderline abnormalities (Figure 5.4)

Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions/mild dyskaryosis (Figures 5.5, 5.6)

High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions/moderate and severe dyskaryosis (Figures 5.7, 5.8, 5.9)

Cytologic indications of invasion (Figure 5.10)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree