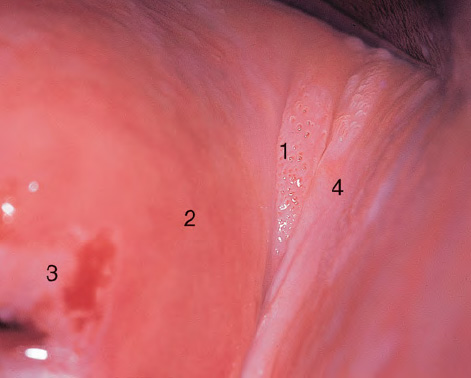

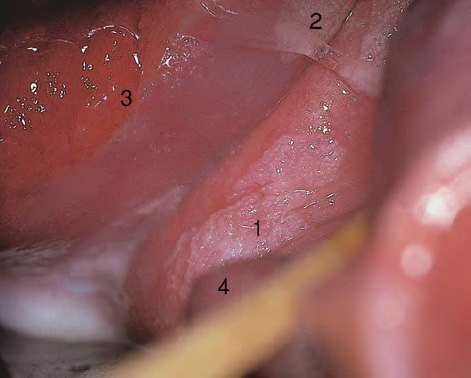

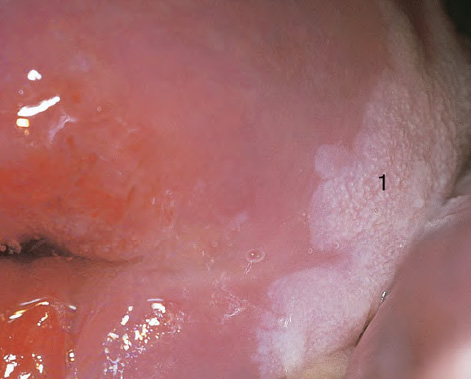

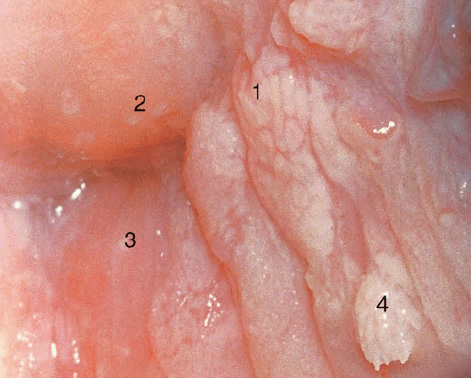

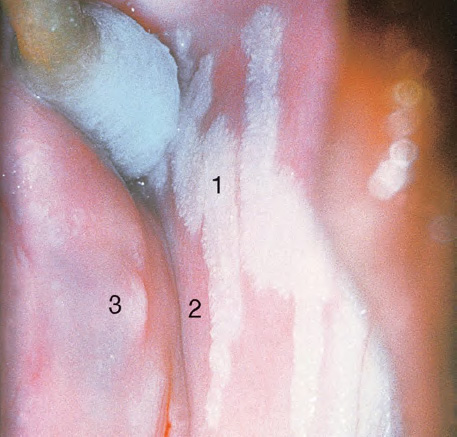

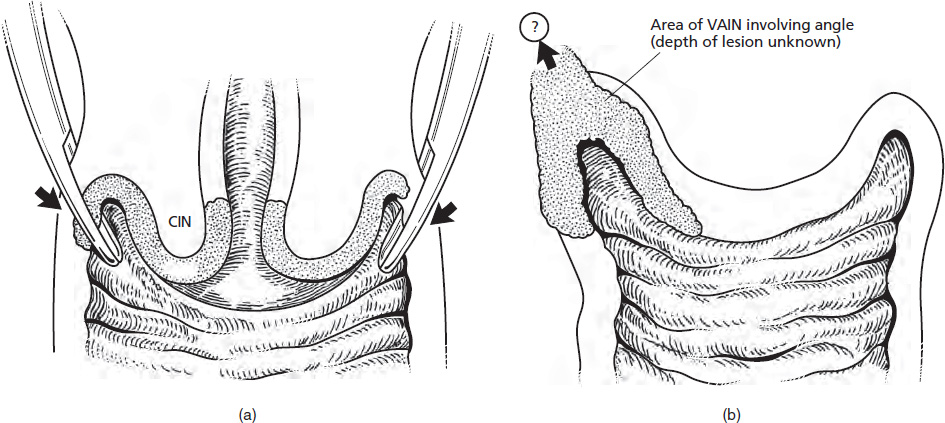

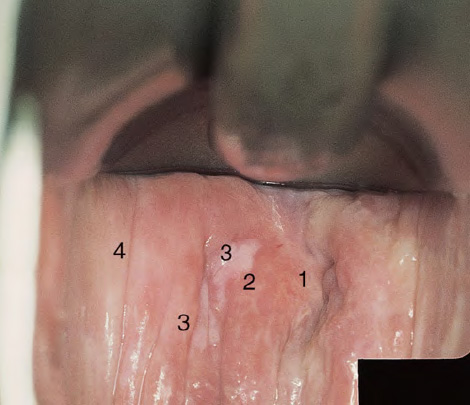

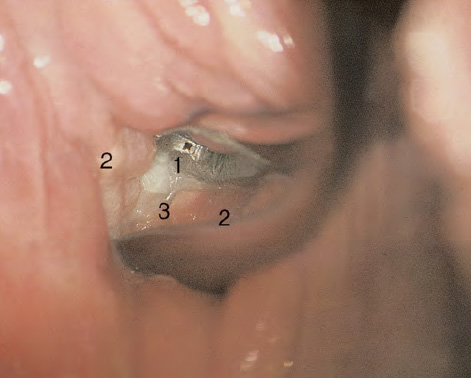

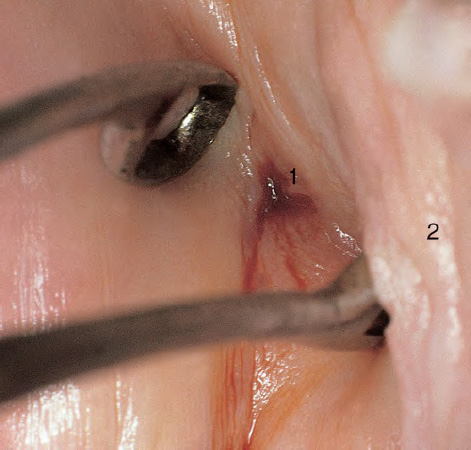

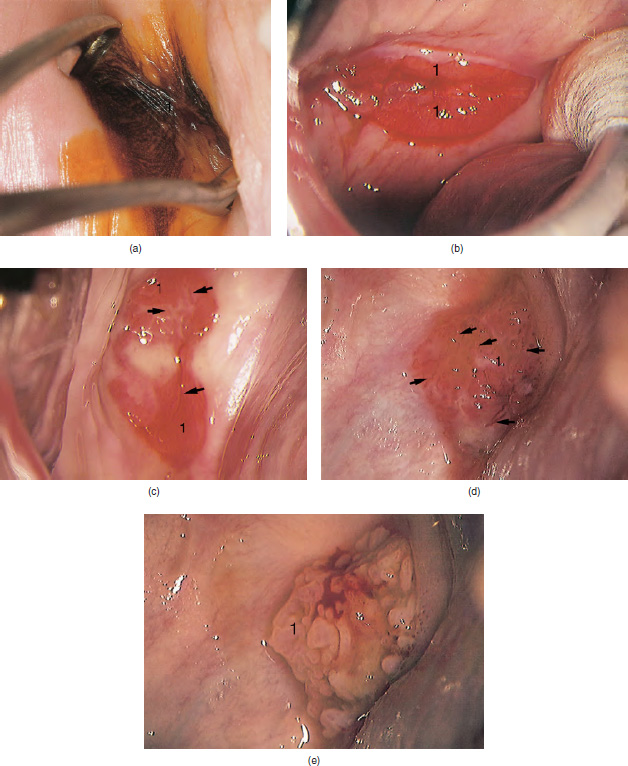

CHAPTER 8 Cancer of the vagina is a rare condition and represents approximately 1–3% of all gynecologic malignancies. The majority of these are squamous cell lesions, but some rarer conditions, such as clear cell adenocarcinoma and melanomas, occur from time to time. The majority of the invasive lesions are found when they produce clinical symptoms, and rarely occur subsequent to the management of true preinvasive conditions. The precancerous stage of the invasive squamous cell disease occurs in the form of an intraepithelial neoplastic condition termed vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN). Recently (2012) the International Federation of Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy has published an updated terminology for normal and abnormal colposcopic patterns in the vagina, the latter including VAIN (Table 8.1). Table 8.1 Clinical and colposcopic terminology of vaginal lesions by the International Federation of Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy From Bernstein J, Bentley J, Bösze P, et al. 2011 Colposcopic Terminology of the International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:166–72. With permission. VAIN is uncommon, accounting for approximately 0.4% of lower genital tract intraepithelial disease but, like vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), has increased in recent years; it is now found in younger females and this rise seems to be associated with the increased prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) infections of the genital tract. Its incidence is estimated at 0.2/100 000 compared with the rate for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) of 36.4/100 000. There appear to be four populations of women who are at increased risk of developing VAIN. The first, which forms the majority, is those women who have already undergone procedures to deal with a pre-existing cervical precancer (CIN). Treatment may have been in the form of a local conservative procedure, using laser, loop diathermy, or cryotherapy. It is estimated that up to 1–3% of patients with cervical neoplasia have either coexisting VAIN or will develop it at a later date. The time at which this will occur may be as short as 2 years or may extend up to 17 years. There also seems to be an increased risk of VAIN in those who have VIN. The second population comprises those who have had radiation therapy for cervical cancer. This increased incidence of VAIN may take some 10–15 years to manifest itself after the initial radiation therapy; it has been suggested that the epithelium of the vagina may be sensitized by low-dose radiation for the subsequent development of neoplasia. The third population consists of those who have had a hysterectomy as treatment for CIN, and in whom a vaginal abnormality is diagnosed during follow-up. About 70% of women with VAIN had undergone hysterectomy. This presentation was more common in the past, when relatively few patients had the advantage of a colposcopic assessment of their CIN before being treated by hysterectomy. In many cases, part of the pre-existing cervical lesion extended into the vaginal fornix and was not included in the surgical resection. Between 1% and 6% of cervical and vaginal (forniceal) intraepithelial lesions coexist, and in some 67% of them a confluence between the two areas is present. The incidence of VAIN 10 years after hysterectomy follow-up is 0.9%. It is in this area of abnormal (atypical) epithelium (with its extension of CIN) that the subsequent VAIN and invasive cancer would seem to develop. The age range for those who may develop VAIN extends from 24 to 80 years, with a mean age estimated at around 50 years. In the younger age group there has been a marked increase in association with other epithelial lesions of the genital tract, and this may be related to the increased presence of HPV. The fourth group consists of women who are immunosuppressed, either following renal or other transplants or idiopathically, or in association with human immunodeficiency virus infections. The exact malignant potential of VAIN is still not known. It is assumed that VAIN progresses to invasive disease because of its similarity to intraepithelial disease of the cervix, but, unfortunately, it is difficult to determine either the number or the type of VAIN lesions that will indeed progress. The lifetime risk of malignant progression of VAIN has been reported at around 10% while more than three-fourths of VAIN lesions may regress back to normal. Furthermore VAIN not associated with CIN or VIN tended to have a higher regression rate (91%) than those with accompanying CIN/VIN. With the advent of the quadrivalent prophylactic vaccine against HPV-induced lower genital tract lesions, there is already evidence of efficacy of its ability to reduce the rate of VAIN lesions. It has been assumed for many years that both cervical and vaginal neoplasias share a common etiology, although the direct evidence has been difficult to document. However, indirect evidence comes from a number of associations. The most notable is that vaginal and cervical neoplasias occur synchronously; that cervical cancer survivors have an increased risk of developing vaginal neoplasia as a second primary tumor and vice versa; and that HPVs, which are now recognized as the viral agents involved in the pathogenesis of cervical neoplasias, are present in vaginal tumor tissue. A multicenter case-controlled study of in situ and invasive vaginal carcinomas found that certain parameters of sexual behavior were only modestly related to vaginal cancer risk and that even in women who had reported five or more sexual partners in a lifetime the risk of disease was only 1.4-fold increased. An early age of first intercourse was not found to be associated, and this was surprising given the consistency in the association of these factors with cervical cancer causation. However, in that study, women who reported a history of sexually transmitted diseases, most commonly due to genital warts, were found to be at excess risk of vaginal tumors. It is believed that 70% of tumors are HPV induced, mostly as a result of HPV type 16. Vaginoscopy is the magnified illumination of the vaginal mucosa using a colposcope. Before describing the vaginoscopic features of VAIN, it is important to stress the distribution of VAIN lesions within the vagina. The majority occur in the upper one-third, and the middle and lower thirds are involved by less than 10% of lesions. The majority are also multifocal. When found after a hysterectomy for CIN, they are usually associated with the folds at the vaginal vault in the 3 and 9 o’clock positions, the so-called “dog ears” of the vaginal fornices. Colposcopically, these lesions are usually acetowhite with sharp borders and a granular surface appearance. Occasionally, there is a fine punctation but mosaic or leukoplakic appearances are rarely found. Because of the loose nature of the vaginal mucosa, the contours of the actual lesions are irregular, making their diagnosis sometimes difficult. Vaginoscopy is carried out after the entire vaginal mucosa has been washed with a 5% acetic acid solution. Any excess fluid is wiped off, because the acetic acid causes a burning sensation in the vagina. The mucosal folds of the vagina do present difficulties and lesions may be obscured by prominent folds. When undertaking an examination, it is important to rotate the speculum with the blades fully opened through 360°, especially as it is withdrawn. It may be necessary for hooks to be used to expose those lesions that may be present within the vaginal vault area. The application of Lugol’s iodine solution is most important because VAIN lesions will usually stain light yellow and their sharp borders will be accentuated. Biopsies should be taken of any such lesion, although those present in the vault, especially when no cervix exists, cause problems because of the pain that is induced by sampling. The injection of local anesthetic before biopsy is important. In postmenopausal patients, there is marked atrophy of the vaginal mucosa and interpretation may be difficult. Bleeding may occur as soon as the acetic acid is applied and an intense burning sensation may be induced. The application of topical estrogen cream for up to 3–4 weeks before re-examination is recommended. It is highly likely that most VAIN lesions in the upper vagina originate as an extension of a CIN lesion into the vaginal fornix. VAIN in the upper vagina can coexist in about 3% of women with CIN and in about two-thirds of them the lesions are confluent. This extension of the CIN lesion into the vaginal fornix will sometimes be difficult to diagnose, especially if there are redundant folds of vaginal skin covering the fornix. Figures 8.1–8.3 show examples of such lesions present in the vaginal fornix and associated with the cervical transformation zone. In Figure 8.1, an area of acetowhite epithelium with a papillary surface is present at (1) high in the left vaginal fornix. It occurs in a 64-year-old woman in whom the cervical transformation zone is difficult to differentiate from the native cervical and vaginal epithelium. The canal is at (3) and the ectocervix at (2), and it has the same surface contour and configuration as the vaginal epithelium at (4). Initially, it would seem as though the abnormal (atypical) epithelium at (1) arose de novo in the vaginal fornix. However, displacement of the cervix to the patient’s right side showed this area to be extensive and to occupy the lateral margins of the ectocervix, the vaginal vault, and a small part of the vaginal wall. A similar case exists in Figure 8.2, in which abnormal (atypical) epithelium (1) is likewise present in the left vaginal fornix. It originally was part of the atypical cervical transformation zone, the lateral extension of which on the ectocervix can just be seen at (2). The endocervix is at (3) and vaginal epithelium at (4). In Figure 8.3, a very granular and acetowhite lesion (1) is present on the ectocervix and projects into the vaginal fornix. All the lesions demonstrated in Figures 8.1–8.3 have been proven by biopsy to be high-grade VAIN. VAIN is not uncommonly associated with papillomavirus infection of the vagina. It may sometimes present diagnostic difficulties because of the exaggerated nature of the vaginal rugosity and of the papillary nature of the surface lesions. Examples are shown in Figures 8.4 and 8.5. In Figure 8.4, an area of acetowhiteness with a papillary surface configuration is seen at (1); the ectocervix is at (2) and normal vaginal epithelium at (3). An obvious condylomatous lesion is seen at (4) and this may have the same etiology as the lesion at (1), although punch biopsy of (1) shows it to be composed of a VIN3 with evidence of HPV infection. Biopsy of (4) shows typical condylomatous features. Figure 8.5 demonstrates the multifocal nature of VAIN. The three lesions labeled (1) also have a typical papilloma infection appearance. Diagnosis without biopsy is impossible. Application of Lugol’s iodine solution (Figure 8.6) is of some help in differentiation. The partial uptake of the iodine stain by the lesion alerts the observer to the fact that this lesion is of a lesser degree of epithelial atypia than major-grade lesions that possess a sharper border with more intense iodine-negative staining (Figure 8.8). Punch biopsy of the lesion stained with acetic acid in Figure 8.5 and Lugol’s iodine solution in Figure 8.6 showed it to be a low-grade VAIN. Vaginoscopy is essential to determine the distribution of VAIN within the vagina. The largest possible speculum should be used to perform the examination and should be repositioned frequently to allow inspection of all the mucosal surfaces. The examination of all four walls of the vagina, starting at the apex and working down to the introitus, should be carried out as separate and sequential steps. The speculum must be fully opened and rotated through a 360° circle, especially if the vaginal folds are prominent. The use of Q-tip swabs or hooks is also important in determining the position of the scattered multifocal loculi of VAIN. Employment of such diagnostic aids can be seen in Figure 8.7, where a Q-tip has been inserted between the lateral vaginal wall and the cervix. An acetowhite lesion with sharp borders and an obvious granular surface is seen on the side wall (1) with normal squamous vaginal epithelium at (2). The area of subclinical papillomavirus infection SPI is seen at (3). The Q-tip has been used to open up the area between the latter lesion and the abnormal (atypical) vaginal epithelium; if this had not been done, the appearance would have suggested the extension of the cervical lesion onto the vaginal fornix. This would have prevented the full extent of the lesion becoming visible. The application of Lugol’s iodine solution (Figure 8.8) finally confirms the major-grade character of this lesion. The borders are sharp and no iodine has been taken up by the central area. A punch biopsy of this area can now be undertaken. However, it may be necessary to move the speculum down into the mid or lower vagina and retract the open blades, thereby allowing the mucosal folds, with the associated VAIN, to adopt a convex shape; in this situation, they are much easier to biopsy. When the VAIN lesion is “flattened,” as in Figure 8.7, it will be found that it is difficult to obtain a purchase upon the epithelium with the biopsy forceps, which will tend to slip off the surface. It is therefore important to reposition the speculum, as described above. The application of a hook to elevate the tissue may be helpful. VAIN following a hysterectomy for CIN is very uncommon; various authors quote between 1% and 3% as the prevalence of vaginal recurrence after hysterectomy when a similar lesion previously existed on the cervix. Some authors have quoted a higher frequency of 20% in patients previously treated for CIN. Although the long-term recurrence rate for VAIN is uncertain, it is suggested by many authors that incomplete excision of the vaginal cuff at the time of hysterectomy for CIN may explain these early recurrences. The presence of such a lesion in the vaginal cuff area before 1 year after hysterectomy often represents a failure to diagnose and treat the vaginal component of cervical disease at the time of primary treatment; in many cases, histologic examination of the original uterine specimen reveals disease at the excised surgical margins. The neoplastic process can be present within pre-existing vaginal cuff inclusion cysts or sinuses. Any nodularity or distortion of the vaginal cuff found during hysterectomy must be treated by surgical excision, not only so as to treat the existing VAIN but also to exclude the presence of any occult invasive cancer within these lesions. While most of these cases are diagnosed within a few years of surgery, a different pattern is seen in patients who have a history of previous radiotherapy. This raises the possibility that a sublethal dose of radiation, sufficient to cause cell damage but not cell death, may have been implicated in the etiology. Preoperative colposcopy and staining of the upper vagina with Lugol’s iodine solution should demonstrate the extension of any abnormal (atypical) cervical epithelium onto the vaginal fornix. This will allow a surgeon performing hysterectomy for CIN to determine accurately the amount of vaginal cuff to remove, whether the operation be by the abdominal or by the more preferable vaginal or laparoscopic approach. Indeed, hysterectomy as a treatment for CIN is nowadays uncommon. Figure 8.9a shows a diagrammatic representation of the failure to evaluate preoperatively the extent of CIN. The vaginal angle clamp can be seen applied across an area of CIN that extends into the right vaginal fornix; obviously this extension had not been fully recognized preoperatively. The result is that residual disease is retained postoperatively in the angle of the vagina (Figure 8.9b). These angle clamps should be ligated, the vaginal vault can be left open, and mattress sutures should be avoided in the resuturing of the vault. Hemostasis is obtained by simply oversewing the vaginal edges. No prospective trial to evaluate the efficacy of this procedure has been undertaken. A persistent cellular abnormality in the vaginal smear will alert the gynecologist to the fact that residual disease exists. Vaginoscopy will therefore need to be undertaken. It must be remembered that postoperatively the vaginal vault usually contains recesses at the 3 and 9 o’clock positions; these may incorporate some abnormal (atypical) epithelium with residual disease. In the postmenopausal woman, it may be extremely difficult to visualize these recesses or “dog ears,” and in such a case the procedure should be performed under a light anesthetic. Various ancillary aids, such as a claw device or Desjardins’ or Kogan’s forceps, will need to be employed, as will the application of Lugol’s iodine solution. It will also be important to take special note of those women who have an abnormal cytology following radiation for cervical carcinoma. Women treated in this way could be at high risk of progression to invasive cancer of the vagina over a varying period of follow-up. The radiation changes induced within the vagina may be difficult to evaluate and multiple biopsies of any suspicious epithelium are mandatory. In Figures 8.10–8.13a, the presence of VAIN is sought in a patient presenting with abnormal cytology 2 years after having a total abdominal hysterectomy for CIN3. In Figure 8.10, the vaginal vault recesses can be seen at (1) and (4) with the vaginal vault present in area (2). The recess on the patient’s left is prominent, whereas that on the right is present initially as a longitudinal slit; this will need to be opened with Desjardins’ forceps for a full examination. Normal squamous epithelium is present at that site but two small adjacent areas, marked (3) and (3), indicate the presence of focal acetowhite areas with sharp margins, suggesting the presence of major-grade disease. In Figure 8.11, an examination of the left-hand recess has been undertaken. A small focal acetowhite lesion is visible at (1) with the vaginal vault at area (2). The further continuation of the recess is seen at (3). In Figure 8.12, the right-hand recess has been opened and its upper extent can be seen at (1) with the vaginal vault epithelium at (2). Desjardins’ forceps have been gently inserted into the recess, and in Figure 8.13a these forceps have been opened wide and the base of the recess painted with Lugol’s iodine solution. There is complete uptake of the iodine and therefore no abnormality exists at the apex of the recess. Obviously, excision biopsy of any abnormality found in this area is imperative. A source of confusion in diagnosing possible VAIN arises with the presence of granulation tissue following hysterectomy. It can sometimes be difficult to differentiate, especially because of the abnormal vascularity existing in both benign granulations and those associated with a polypoidal type of VAIN. In Figure 8.13b,c, granulations developed in the vaginal vault (1) and angles (1) after abdominal hysterectomy in cases where persistent CIN made management difficult. Abnormal vessels (arrowed) can be seen in Figure 8.13b and biopsy was essential in both cases to exclude the presence of neoplasia. However, in the case shown in Figure 8.13d,e, in a woman who had previously had four attempts at local destruction of a CIN3 and who eventually had an abdominal hysterectomy, an area of suspicious granulations (1) is seen in the left vaginal horn. In Figure 8.13d, very abnormal vessels (arrowed) are seen and, when acetic acid is applied, the vascularity is lost, but a dense acetowhiteness (1) develops in the tissue. Biopsy of these lesions showed the presence of VAIN3 with early invasion. The role of HPV testing is still to be evaluated. However a number of authors insist that HPV DNA testing is more effective at detecting residual VAIN than is cytology. While the extremely high negative predictive of HPV DNA testing would be reassuring in the case of a mild abnormal cytologic abnormality (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance/low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL)) its eventual position in the follow-up of these women using purely HPV analysis needs to be defined. For example, if such a women has just a positive HPV result then it would be difficult to discover the source of a residual abnormality: it may be as a result of the presence of the virus anywhere in the lower genital tract and not necessarily emanating from the vaginal vault. However, the need or otherwise of vault smears after hysterectomy owing to the increased risk of primary VAIN is still debatable. Certainly after hysterectomy for benign disease there are no valid reasons for vault cytology, although the UK screening program has recently recommended that follow-up after hysterectomy for completely excised CIN should be composed of cytology at 6 and 18 months; however, this may alter with the future introduction of follow-up with HPV testing. Once the patient has been examined and the lesion defined, it is important to take a biopsy in order to produce tissue confirmation. From time to time in the patient who has had a previous hysterectomy and is postmenopausal, it will be difficult to gain access to the upper vagina. The use of acetic acid or iodine may produce further considerable discomfort to the patient because of the thinness and atrophic change in the vaginal skin. It is often worthwhile for the patient to use estrogen cream for 2–4 weeks before returning to the colposcopy clinic for a re-examination; by this time the vaginal skin will have markedly thickened. Sometimes, minor epithelial abnormalities will have disappeared and the major-grade VAIN lesions will be much easier to identify confidently and biopsy. In the postmenopausal woman it may be extremely difficult to obtain an adequate cytologic sample of the vaginal vault epithelium because of marked atrophic changes; attempts to procure an adequate smear from this dry surface may induce bleeding, further obscuring and interfering with the cytologic specimen. In these cases, it is imperative to use estrogens in the form of cream instilled high into the vagina so that, after a few weeks, it will be possible and easier to obtain a satisfactory smear, and also to procure a punch biopsy. The biopsy forceps used in the vagina are a matter of the clinician’s personal preference. Mention has already been made of the need to readjust the vaginal speculum to make the mucosal surface and its accompanying abnormal (atypical) epithelium more accessible to the biopsy instrument. Such a situation can be seen in Figure 8.14, where an Eppendorfer biopsy forceps is being used to remove an area of iodine-negative tissue (1) present high on the posterior vaginal wall (2). A full-thickness block of tissue can be satisfactorily removed and the pathologist is then able to identify any associated VAIN lesion. Bleeding of any significant degree is uncommon, and if it does occur then it can be easily stopped by the quick application of either silver nitrate or Monsel’s solution (ferric subsulfate).

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia

8.1 Introduction

Section

Pattern

General assessment

Adequate or inadequate for the reason (e.g., inflammation, bleeding, scar) transformation zone

Normal colposcopic findings

Squamous epithelium: mature or atrophic

Abnormal colposcopic findings

General principles:

Upper third or lower two-thirds

Anterior, posterior, or lateral (right or left)

Grade 1 (minor):

Thin acetowhite epithelium, fine punctation, fine mosaic

Grade 2 (major):

Dense acetowhite epithelium, coarse punctation, coarse mosaic

Suspicious for invasion:

Atypical vessels

Additional signs: fragile vessels, irregular surface, exophytic lesion, necrosis ulceration (necrotic), tumor or gross neoplasm

Non-specific:

Columnar epithelium (adenosis)

Lesion staining by Lugol’s solution (Schiller’s test): stained or non-stained, leukoplakia

Miscellaneous findings

Erosion (traumatic), condyloma, polyp, cyst, endometriosis, inflammation, vaginal stenosis, congenital transformation zone

8.2 Natural history of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia

8.3 Etiology

8.4 Clinical presentation

Vaginoscopy

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia seen as an extension of the cervical atypical transformation zone

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia as seen in association with human papillomavirus lesions

8.5 Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia following hysterectomy

Presentation after hysterectomy: value of cytology and human papillomavirus testing

8.6 Biopsy of the vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia lesion

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree