Control of Exsanguinating External Hemorrhage

William Tsai

Kathleen Brown

Introduction

The control of exsanguinating external hemorrhage is an important skill needed in the treatment of childhood injuries. While most injuries to children involve minimal blood loss, significant injuries to soft tissues and vascular structures may result in rapid exsanguination, multisystem organ failure, and death. In addition, because of anatomical and physiologic differences between children and adults, significant blood loss may be unrecognized, and blood loss that might be considered inconsequential in an adult may threaten the life of a child. Therefore, it is essential that all personnel who care for injured children be adept at using techniques designed to stop or limit hemorrhage.

Anatomy and Physiology

Injuries that result in exsanguination involve damage to blood vessels in two general anatomic locations. The peripheral vessels lie in the tissues above the fascia. These vessels are usually small, are rarely a source of significant bleeding, and respond well to basic methods of hemorrhage control. Central vessels lie deep to the fascia and are at risk in penetrating trauma, significant blunt trauma, and fractures. Injury to these vessels may result in significant external hemorrhage. Bleeding from peripheral and central veins is manifested by continuous flow of dark-colored blood. On the other hand, arterial hemorrhage is seen as bright red, pulsatile blood.

Important differences in anatomy and physiology between adults and children should be noted. First, because children have a smaller body mass than adults, trauma results in greater force applied per unit body area (1). Second, this greater force is applied to a body with less subcutaneous fat and protective connective tissue and results in a relative increased exposure of vital structures (1). Third, children have an enhanced ability to maintain blood pressure in the face of significant blood loss. Tachycardia and decreased skin perfusion may be the only signs of significant hemorrhagic shock and may only occur with at least a 25% diminution in blood volume (1). A drop in blood pressure is a late sign of shock in children and may signal imminent cardiac arrest (2).

Indications

Lacerations, puncture wounds, gunshot wounds, soft-tissue injuries, and traumatic amputations are all indications for immediate control of hemorrhage. In general, the basic procedures of hemorrhage control should first be employed. The clinician should then proceed to the advanced procedures when these basic procedures have failed.

Procedures

Basic Procedures

Manual Pressure

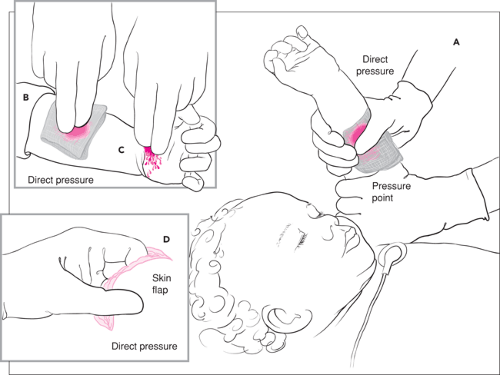

Direct pressure controls most bleeding as soon as it is initiated (Fig. 28.1). Using a gloved hand and sterile gauze, direct and constant pressure over the bleeding site should be applied. Care should be taken to determine that pressure is being applied to the proper site of bleeding because dressings and the confusion associated with other interventions may obscure the bleeding site and cause pressure to be directed in the vicinity

of but not directly on the source of bleeding. An acceptable alternative is to apply direct pressure with a gloved finger (3,4). Bleeding from the edge of a large tissue flap may be controlled by pinching the bleeding site between the thumb and forefinger. Ideally, when either of these methods is used, pressure should be applied for a specific period of time, usually at least 10 to 15 minutes. Time passes slowly when performing a monotonous activity such as holding pressure, so it is best to use a timepiece to ensure that pressure is maintained for the desired duration.

of but not directly on the source of bleeding. An acceptable alternative is to apply direct pressure with a gloved finger (3,4). Bleeding from the edge of a large tissue flap may be controlled by pinching the bleeding site between the thumb and forefinger. Ideally, when either of these methods is used, pressure should be applied for a specific period of time, usually at least 10 to 15 minutes. Time passes slowly when performing a monotonous activity such as holding pressure, so it is best to use a timepiece to ensure that pressure is maintained for the desired duration.

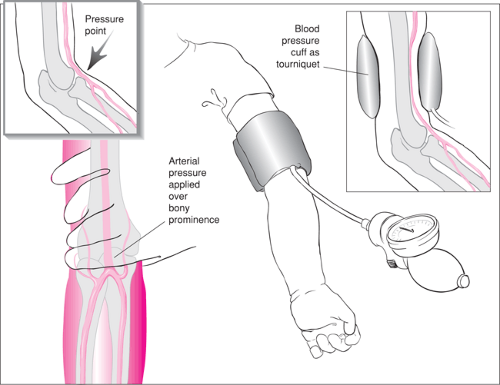

Control of high-pressure arterial bleeding may be facilitated by applying pressure proximal to the site of bleeding. The pressure point is identified by locating the arterial pulse proximal to the site of bleeding, then compressing the artery with the fingers. Pressure exerted at these areas serves to reduce blood flow at the site of hemorrhage. The ideal pressure point is an area where the artery passes in close proximity to a bone or other firm anatomic structure against which it may be compressed. It may be necessary for the clinician to palpate along the course of the artery to identify the best site at which to apply pressure (Fig. 28.2).

Elevation of the Bleeding Area

When possible, elevation of the injured area may reduce hemorrhage. In optimal circumstances, the area should be elevated to a height above the level of the heart. If this is not possible, the bleeding site should be kept level with the rest of the body and not allowed to become dependent.

Pressure Bandages

Pressure bandages may be used as a temporary alternative to direct pressure when the patient has other, more severe injuries that require the attention of all available personnel. The procedure is performed by first placing a stack of gauze pads approximately 1 inch thick directly over the site of bleeding. An elastic bandage is then wrapped over the gauze pads tight

enough to provide adequate hemostasis. Some commercial variations of pressure bandages employ a semirigid styrene block placed directly over the site of bleeding, which is first covered by a gauze pad. The block is then pressed and molded into the wound by an elastic overwrap (5).

enough to provide adequate hemostasis. Some commercial variations of pressure bandages employ a semirigid styrene block placed directly over the site of bleeding, which is first covered by a gauze pad. The block is then pressed and molded into the wound by an elastic overwrap (5).

Figure 28.2 Pressure may be applied proximal to a site of bleeding using either manual pressure applied at a pressure point or, in more severe cases, an inflated blood pressure cuff. |

Pressure bandages do have potential complications. If wrapped too tightly, they can lead to distal ischemia; therefore, distal perfusion should be monitored frequently, every 30 minutes at a minimum, while the pressure bandage is in place. If wrapped too loosely, the pressure bandage will not stop the bleeding but will instead obscure it, and the child may exsanguinate.

Topical Vasoconstrictors

Epinephrine solution (1:1000) can be diluted in saline and applied to gauze pads that are then placed over the wound. This solution works well to control areas of persistent low-pressure bleeding, particularly when a tissue bed continues to ooze blood. Care must be taken to avoid injection of this solution into a vessel, and large volumes should not be administered, as epinephrine can be absorbed by the tissues and can cause clinical effects. Epinephrine should not be used on fingers, toes, the penis, ears, or the tip of the nose because of the risk of vasoconstriction that may result in tissue necrosis. An additional mode of topical therapy involves direct application of fibrin or gel-foam to the site of bleeding.