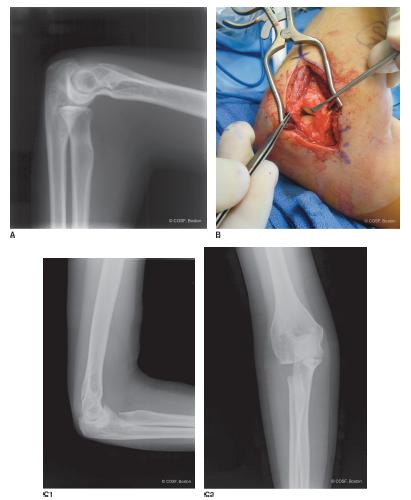

FIGURE 16-1 A: Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of congenital posterolateral radial head dislocation. The patient is now developing pain with activities of daily living and recreation. B: Sagittal MRI scan reveals impingement and effusion.

Clinical Evaluation

The degree and direction of dislocation, along with associated conditions, affect the timing of presentation. Most isolated congenital dislocations do not present for evaluation and care until later in life, often around school age. The child’s lack of full elbow extension or forearm rotation may only be noted when specific arm and hand motion tasks are attempted under direct supervision or observation. The child’s compensatory shoulder and wrist motion usually prevents functional limitations and parental awareness until direct observation and inspection occurs. This is similar to the presentation of radioulnar synostosis (see Chapter 17).

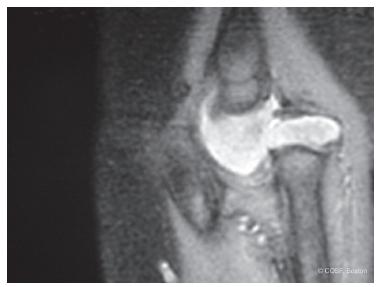

FIGURE 16-2 Sagittal MRI scan of rare anterior congenital radial head dislocation with impingement against a hypoplastic capitellum.

Early on, pain is rare, if present at all. Occasionally, the children will complain of instability with forearm rotation, or the parents will hear a snapping sound with rotatory motion in the subluxed or minimally dislocated situation13 (Figure 16-3). Later, osteochondral deterioration of the radial head and capitellum can create activity-related pain, produce loose bodies, and cause locking and crepitus. Some of these children present acutely to the emergency room with a locked joint or, more commonly, pain with activities such as sports.14

Finally, some adolescents only present when they are disturbed by the aesthetic appearance of a prominent posterolateral dislocation. Their desire for excision is more psychosocial than functional.

Examination of an isolated posterolateral dislocation usually reveals a 5- to 40-degree lack of elbow extension and <50% full forearm rotation. There is often compensatory wrist and shoulder rotation that prevents functional impairment. Bilateral involvement can be more disabling. With local dysplasia or syndromic conditions, the limitations on exam become more regional or systemic. If there is hand and/or brain involvement, the functional limitations become more marked.

FIGURE 16-3 A: Mild posterolateral lateral radial head subluxation with marked pain and snapping. B: Modified Kocher posterolateral exposure of the congenital dislocation. C1,2: Postoperative anteroposterior and lateral elbow x-rays demonstrating radial head excision at the desired level. D: Forearm x-ray revealing radial head resection and neutral ulnar variance.

Radiographs will reveal the direction of dislocation. The contour of the radial head; bowing of the radial neck and shaft; radiocapitellar, proximal, and distal radioulnar articulations; distal ulnar variance; and shape and contour of the ulna are all evaluated on plain radiographs of the forearm, wrist, and elbow. Other regional anatomic abnormalities, such as radioulnar synostosis, are recorded. Osteochondral deterioration is noted. On rare occasions in which the diagnosis is made perinatally or in infancy, ultrasound or MRI scan is used to determine the feasibility of an open reduction.

Surgical Indications

One of the lessons of history is that nothing is often a good thing to do and always a clever thing to say .

—Will Durant

The ideal surgical solution for a congenital dislocation of the radial head includes (1) early recognition by prenatal or infantile ultrasound and (2) successful operative reduction of the radial head that leads to proximal radioulnar and radiocapitellar joint remodeling, normal alignment, and motion. The first is often difficult, and there is debate if the second is achievable. Too often these children are not diagnosed until later in life due to minimally noticeable disability. It is not a common or severe enough problem to warrant neonatal screening, such as with developmental dysplasia of the hip. Usually at the time of diagnosis, there is too much radial head and capitellar deformity to warrant open reduction.7,15–17 Remodeling will not occur with reduction at this stage. The only surgical option is radial head excision when and if pain and progressive limitation of motion and function develop.1,18,19

The evidence for successful open reduction and reconstruction of a congenital dislocation is limited to small retrospective case series or case reports.13,20,21 There are plenty of reports of failed reconstruction. Natural history is asymptomatic in some patients through to adulthood. Thus, the presence of a congenital radial head dislocation alone is not an indication for surgery.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Radial Head Excision

Radial Head Excision

The technical aspects of radial head excision are not hard. It is deciding “if and when” to operate that is key. The presence of a radial head dislocation alone is not an indication for excision. Unremitting and unresolved pain with other treatment modalities can be a proper indication. Limitations in elbow extension and forearm rotation without pain are not an indication for surgery. Athletes desiring more motion for sports such as tennis or gymnastics could be very disappointed by their lack of improvement or the development of wrist pain with radial head excision. Conversely, skeletal immaturity is not always a contraindication to radial head excision. In some young patients, there are progressive osteochondral injury, deformity, loose bodies, and marked pain that responds to radial head excision.18 Finally, there are adolescents with marked posterolateral dislocations who have radial head excision for predominately aesthetic benefit.19 The degree of ulnar variance at the wrist should be radiographically measured before consideration for radial head excision. If there is a positive variance, radial head excision can lead to or worsen wrist pain.

The patient is placed supine with a fluoroscopic arm table for the affected limb. A standard posterolateral approach is utilized through the anconeus-extensor carpi ulnaris interval. The lateral collateral ligament is preserved anteriorly. The capsule is opened and radiocapitellar joint is inspected (Figure 16-3B). The capitellum is generally deformed with marked osteochondral injury (Figure 16-4). The radial head usually has similar arthritic-like deterioration (Figure 16-5A). Dissection is carried down the radial neck while preserving the annular ligament and protecting the posterior interosseous nerve. Excision of the radial head is carried out extraperiosteally to lessen the risk of reformation of bone that could lead to recurrent impingement. The bone cut is made perpendicular to the diaphyseal forearm rather than the radial neck, as the neck is bowed posteriorly in the usual posterolateral dislocation. The cut can be started with the saw (Figure 16-5B) but is usually finished with an osteotome for better control and less risk of chondral or nerve injury in the tight space. Fluoroscopy is used to determine the level of excision and proper angle of cut to prevent impingement (Figure 16-3C). Biceps tendon insertion is preserved. Full forearm rotation should be possible with improved flexion-extension arc.

FIGURE 16-4 Operative exposure revealing capitellar deformity and degenerative change with chondral thinning from a congenital radial head dislocation and now pain in adolescence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree