FIGURE 18-1 A: Obvious deformity of right clavicle due to a congenital clavicular pseudarthrosis. B: AP x-ray of same patient. C: CT scan revealing wide diastasis of the narrow, sclerotic bony fragments.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

- What causes congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle?

- What are the conditions associated with congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle?

- What is the natural history?

- What are the surgical indications for repair?

- Is the type of surgery time dependent?

- What are the complications of both natural history and surgery?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

The obscure we see eventually. The completely obvious, it seems, takes longer.

—Edward R. Murrow

The clavicle is an S-shaped bone overlying the subclavian vessels and brachial plexus. This bone articulates medially with the sternoclavicular joint and laterally with the acromioclavicular joint. The two membranous primary centers of ossification appear at about 6 weeks postconception and fuse about 1 week later. The medial cartilaginous mass contributes more to clavicular growth than the lateral mass does. The junction of the two centers of ossification is between the medial two-thirds and lateral third of the clavicle.

Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle is a failure of coalescence of these two centers. The congenital nonunion is hypertrophic and can be progressive in size with growth. This nonunion can lead to local neurovascular compression.1, 2 Definitive treatment involves open repair with bone grafting.3

Etiology and Epidemiology

Congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle is a rare condition, most often presenting as an isolated anatomic variation.4–7 Unilateral cases almost universally affect the right clavicle. There can be an associated high first rib and/or cervical rib. Left-sided presentation does occur8 and is generally associated with dextrocardia and situs inversus.

The theory is that the failure of consolidation of the ossification centers is related to the high subclavian artery on the right side (or left side in dextrocardia).5 Bilateral cases do occur. There is a familial incidence.9 Associated conditions include cleidocranial dysostosis, neurofibromatosis, trisomy 21, and other rarer syndromes (Goltz, Floating Harbor, Prader Willi, chromosome 10p deletion). Histologic evaluation of the pseudarthroses indicates enchondral ossification on both sides of the resected specimens, indicative of failure of coalescence of the two primary centers of ossification.10,11

Clinical Evaluation

These children generally present with a right-sided prominence of their diaphyseal clavicle. There may be a foreshortened shoulder girth. Initially, this foreshortening is usually asymptomatic. The children may present at birth (Figure 18-2). In some respects, early presentation is most fortunate because surgery is less invasive in infancy.12 The prominence often increases in size with growth. Range of motion, strength, and sensibility testing are generally normal at presentation. Later, patients may develop signs and symptoms of thoracic outlet syndrome due to the compressive effect of the pseudarthrosis on the underlying neurovascular structures in certain positions. This effect includes numbness in C8–T1-ulnar nerve distribution; loss of radial pulse in abduction and external rotation of the shoulder; and, at times, weakness of the hand and arm, especially with overhead activities.13,14 Radiographs at any age will reveal the obvious pseudarthrosis.15,16 Magnetic resonance imaging or CT scan may help better define neurovascular compromise or bony anatomy.

FIGURE 18-2 Radiograph of an infant with pseudarthrosis. This should not be mistaken for traumatic birth fracture.

Associated conditions such as cleidocranial dysostosis are evaluated. Generally, pseudarthrosis of the clavicle is an isolated anatomic variant. It can be post-traumatic or associated with neurofibromatosis. Either way, the treatment is the same: observation17 or surgical intervention. Attempts can be made to lessen the thoracic outlet symptoms with postural and scapular stabilization exercises, but this condition usually comes to surgery. There are reports of vascular lesions including aneurysm of the subclavian artery or vein, acute ischemia, and subclavian vein thrombosis in adulthood in association with congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle.18–20 These worrisome reports make surgical repair in childhood seem more urgent. Vascular studies should be undertaken in symptomatic patients with pseudarthrosis of the clavicle whose radial pulse disappears during postural tests. Duplex Doppler of the subclavian artery is an excellent screening exam, but selective arteriography is the gold standard.

Surgical Indications

There is debate if the mere presence of a congenital pseudarthrosis of the clavicle is an indication for operative intervention. There are reports of asymptomatic individuals into adulthood. However, there are also worrisome reports of late vascular insufficiency and/or thoracic outlet syndrome in adulthood in untreated patients. Most patients either become symptomatic or are bothered enough by the aesthetics of their prominent pseudarthrosis that they come to surgical reconstruction before adulthood.21,22

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Resection of Pseudarthrosis, Bone Grafting, and Internal Fixation

Resection of Pseudarthrosis, Bone Grafting, and Internal Fixation

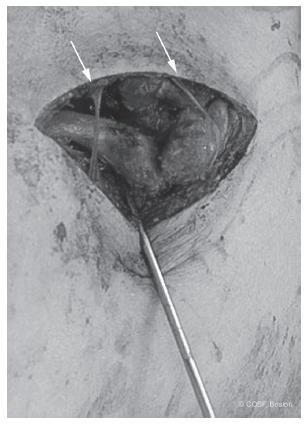

In the noninfant, surgical reconstruction for congenital pseudarthrosis follows the same principles as reconstruction for post-traumatic clavicular nonunion23 (see Chapter 25). An incision in the skin lines is placed just below the clavicle to lessen the prominence postoperatively. The cutaneous nerves are identified and protected. Subperiosteal exposure of the clavicle is performed initially medial and lateral to the pseudarthrosis; then careful dissection is performed at the nonunion site (Figure 18-3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree