2Pathology Department, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK

Overview

- Congenital anomalies of the breast are not uncommon but can cause considerable anxiety. Treatment improves patients’ lives immeasurably

- Most benign abnormalities occur against the background of breast development, reproduction and involution

- Increasing numbers of men are attending breast clinics with breast enlargement

- Most conditions that affect the breast are benign and there are a huge range of these conditions

- Atypical hyperplasia is the only benign condition associated with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer

Congenital Abnormalities

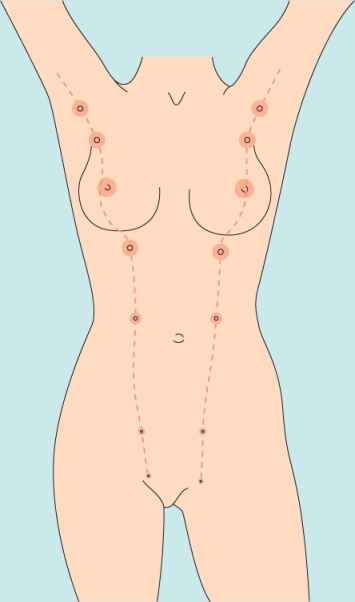

Extra Nipples and Breasts

Between 1% and 5% of men and women have supernumerary or accessory nipples or, less commonly, supernumerary or accessory breasts. These usually develop along the milk line: the most common site for accessory nipples is just below the normal breast (Figures 2.1–2.3), and the most common site for accessory breast tissue is the lower axilla (Figure 2.4). Accessory breasts below the umbilicus are extremely rare. Extra breasts or nipples only require treatment if they are unsightly. They are subject to the same diseases as normal breasts and nipples.

Absence or Hypoplasia of the Breast

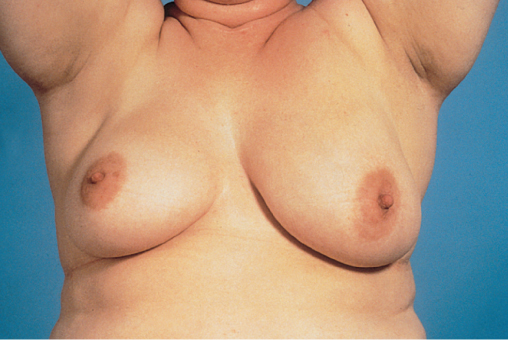

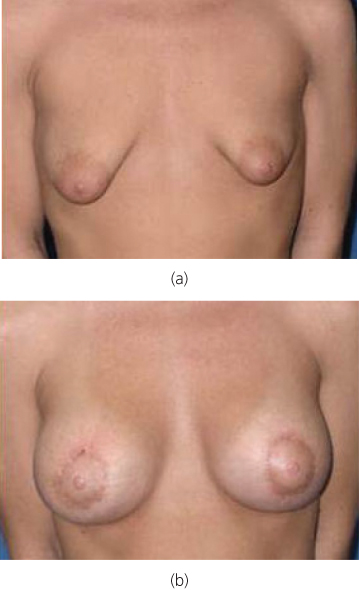

One breast can be absent or hypoplastic (Figure 2.5), usually in association with defects in one or both pectoral muscles. Some degree of breast asymmetry is usual, and the left breast is more commonly larger than the right. True breast asymmetry can be treated by augmentation of the smaller breast, or both breasts, reduction or elevation of the larger breast, or a combination of procedures. Hypoplastic breasts are often tubular in morphology, so reshaping of the breast and division of any constricting bands together with the use of tissue expanders to reshape the breast prior to implant insertion is often required.

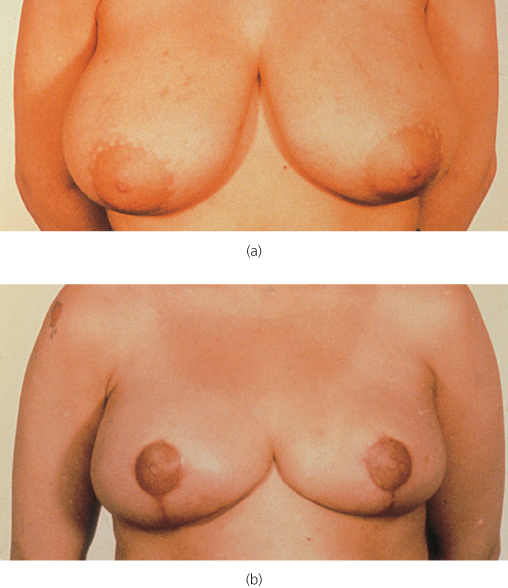

Figure 2.5 (a) Hypoplasia of left breast prior to surgery. (b) Hypoplasia of left breast following bilateral tissue expansion and placement of shaped breast implants.

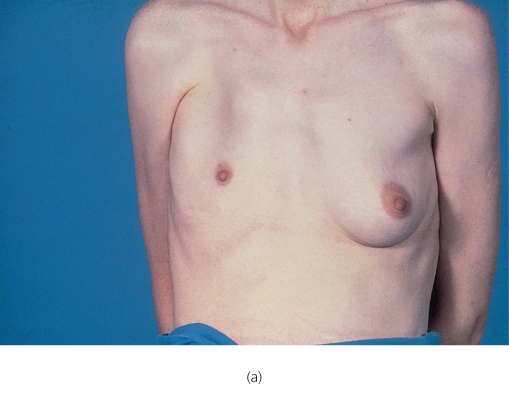

Tubular Breasts

This is a congenital anomaly of the breast that manifests itself at puberty. The breast has a narrow base and resembles an hourglass (Figure 2.6). Surgical correction involves making incisions into the base of the breast to allow the constricted base to unfold.

Figure 2.6 (a) Tubular breasts. (b) Tubular breasts after surgical correction.

This is combined either with tissue expansion followed by implant insertion or use of an implant alone (Figure 2.6(b)). The condition can be unilateral or bilateral.

Chest Wall Abnormalities

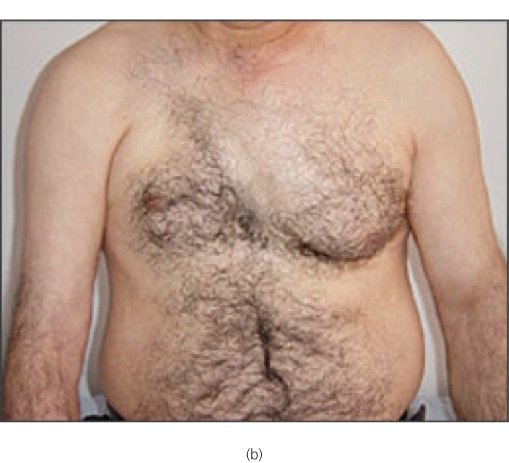

About 90% of patients with true unilateral absence of a breast (Figure 2.7) have either absence or hypoplasia of the pectoral muscles (Figure 2.8). In contrast, 90% of patients with pectoral muscle defects have normal breasts. Some patients have abnormalities of the pectoral muscles and absence or hypoplasia of the breast associated with a characteristic deformity of the upper limb. This cluster of anomalies is called Poland’s syndrome and is more common in men than in women (Figure 2.9). Abnormalities of the chest wall, such as pectus excavatum, and deformities of the thoracic spine, such as scoliosis, can also result in normal symmetrical breasts seeming asymmetrical.

Figure 2.9 (a) Poland’s syndrome with hypoplasia of right breast and absent chest wall muscles (patient also had typical hand abnormality). (b) Poland’s syndrome in a male.

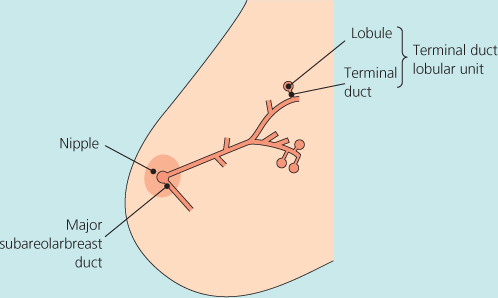

Breast Development and Involution

The breast is identical in boys and girls until puberty. Growth begins at about the age of 10 and may initially be asymmetrical: a unilateral breast lump in a 9–10-year-old girl is invariably a developing breast, and biopsy specimens should not be taken from girls of this age as this can damage the breast bud. The functional unit of the breast is the terminal duct lobular unit or lobule (Figures 2.10 and 2.11), which drains via a branching duct system to the nipple. The duct system does not run in a truly radial manner and the breast is not separated into easily defined segments. The lobules and ducts—the glandular tissue—are supported by fibrous tissue—the stroma. Most benign breast conditions and almost all breast cancers arise within the terminal duct lobular unit.

After the breast has developed, it undergoes regular changes related to the menstrual cycle. Pregnancy results in a doubling of the breast weight at term and the breast involutes after pregnancy. In nulliparous women breast involution begins at some time after the age of 30. During involution the breast stroma is replaced by fat so that the breast becomes less radiodense, softer and ptotic (droopy). Changes in the glandular tissue include the development of areas of fibrosis, the formation of small cysts (microcysts) and an increase in the number of glandular elements (adenosis). The life cycle of the breast consists of three main periods: development (and early reproductive life), mature reproductive life and involution. Most benign breast conditions occur during one specific period and are so common that they are best considered as aberrations rather than disease (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Aberrations of normal breast development and involution.

| Age (years) | Normal process | Aberration |

| <25 | Breast development: | |

| Stromal | Juvenile hypertrophy | |

| Lobular | Fibroadenoma | |

| 25–40 | Cyclical activity | Cyclical mastalgia; cyclical nodularity (diffuse or local) |

| 35–55 | Involution: | |

| Lobular | Macrocysts | |

| Stromal | Sclerosing lesions | |

| Ductal | Duct ectasia |

Aberrations of Breast Development

Juvenile or Virginal Hypertrophy

Prepubertal breast enlargement is common and requires investigation only if it is associated with other signs of sexual maturation. Uncontrolled overgrowth of breast tissue can occur in adolescent girls whose breasts develop normally during puberty but then continue to grow, often quite rapidly. No endocrine abnormality can be detected in these girls.

Patients present with social embarrassment, pain, discomfort and inability to perform regular daily tasks (Figure 2.12). Reduction mammoplasty considerably improves their quality of life and should be more widely available (Figure 2.13).

Figure 2.13 (a) Patient with juvenile hypertrophy before surgery. (b) Patient with juvenile hypertrophy after surgery.

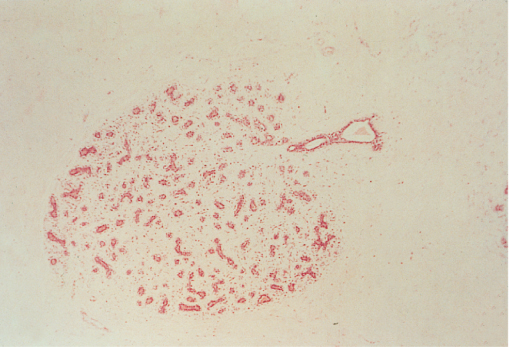

Fibroadenoma

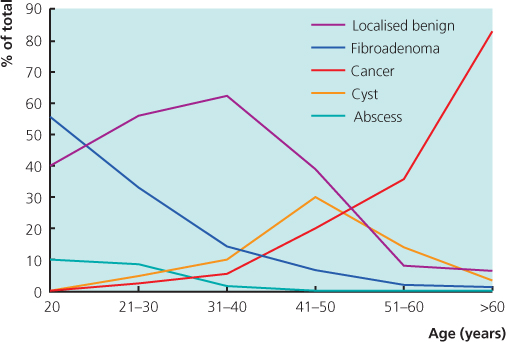

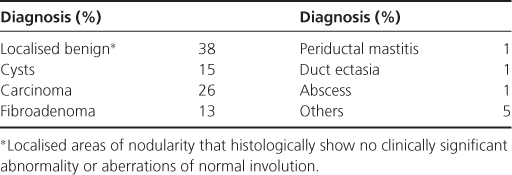

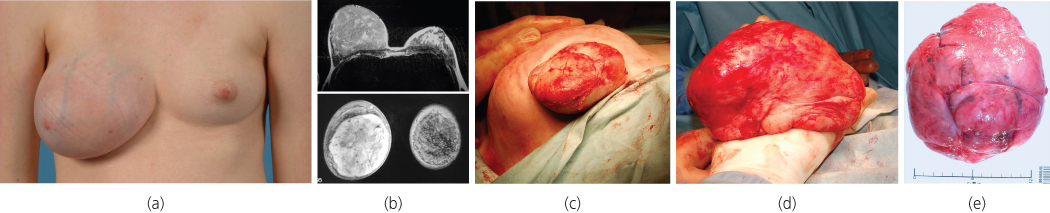

Although formerly classified as benign neoplasms, fibroadenomas are best considered as aberrations of normal development: they develop from a whole lobule and not from a single cell. They are common and are under the same hormonal control as the rest of the breast tissue. Fibroadenomas account for about 13% of all palpable symptomatic breast masses, but in women aged 20 they account for almost 60% of such masses (Figure 2.14; Table 2.2). There are three separate types of fibroadenoma: common fibroadenoma, giant fibroadenoma and juvenile fibroadenoma. There is no universally accepted definition of what constitutes a giant fibroadenoma, but most experts consider that it should measure over 5 cm in diameter. Juvenile fibroadenomas occur in adolescent girls and sometimes undergo rapid growth, but are managed in the same way as the common fibroadenoma (Figure 2.15).

Table 2.2 Final diagnosis in patients with palpable breast mass.

Figure 2.15 (a) Juvenile fibroadenoma of right breast. (b) MRI of juvenile fibroadenoma of right breast. (c) Juvenile fibroadenoma of right breast being excised. (d) Juvenile fibroadenoma after excision. (e) Juvenile fibroadenoma after excision showing size.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree