Scaling brown macules and patches, at least part of which appear reticulated and papillomatous

Involvement of upper trunk and neck

Fungal staining is negative for fungus

No response to antifungal treatment

Excellent response to minocycline

Epidemiology

Occurs after puberty

Present for years before diagnosis

No gender predilection

CRP is an uncommon skin condition with an incidence among Lebanese population of 0.02 % in a clinic-based study [4]. Most patients have the lesions for many months to years, and the majority have disease onset after puberty. At presentation, the skin eruption has usually been present for 1–4 years. The age at onset of skin eruption ranged from 8 to 32 years [3, 4] with the mean age of 15 years noted in one study [3]. There is no gender predilection.

Clinical Presentation

Tan to brown scaly macules, patches, and plaques

Asymptomatic

Seborrhoeic areas of trunk

Skin lesions consist of reticulated, hyperpigmented tan to brown macules, patches, and plaques that are confluent centrally on the chest (especially intermammary on the chest) and back, with reticulation of lesions as they extend away from the midline (Fig. 10.1). In the majority of cases, scales are present. In many patients, mild erythema is also described; however, this may be obscured by dark pigmentation in patients who are Fitzpatrick types V and VI. The most common areas involved include the chest, shoulders, neck, axilla, and back. CRP can unusually affect the face and feet. A vast majority of the patients are asymptomatic while a few complain of pruritus.

Fig. 10.1

Reticulated brown patches over the chest (courtesy of Prof Ruiz-Maldonado)

The main differential diagnoses to consider are acanthosis nigricans, tinea versicolor, seborrhoeic dermatitis, epidermal nevus, verruca plana, SCURF (dirt), and Darier’s disease.

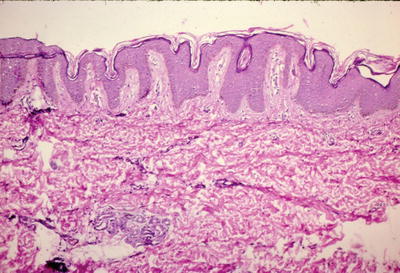

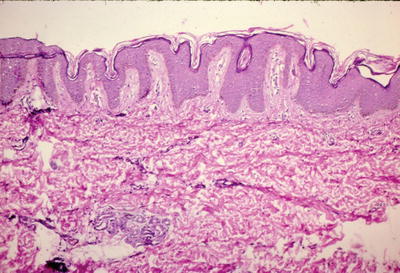

Histopathological findings are consistent with a hyperproliferative disorder. Epidermal changes include hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, variable acanthosis, and sparse dermal inflammation (Fig. 10.2). Some reports have demonstrated the presence of both yeast and hyphae in association with CRP [4–7].

Fig. 10.2

Photomicrograph showing mild orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, marked papillomatosis, variable acanthosis, and sparse dermal inflammation cells. Haematoxylin and eosin ×40

Pathogenesis

Not well understood

May be regarded as a genetic disorder of keratinisation with abnormal response to Malassezia Furfur

The cause of CRP is not fully known. The main theory that has been advocated is that this entity results from an abnormal host reaction to Malassezia furfur [2]. Other proposed causes include endocrine imbalance and UV exposure [8]. Genetic susceptibility has been suggested in case reports of familiar CRP [9, 10]. It is been thought that CRP may be regarded as a genetic disorder of keratinisation with an abnormal response to secondary colonisation to M. furfur.

Treatment

Minocycline treatment of choice

Require 1–3 months of treatment

Mediate changes through anti-inflammatory actions

Carteaud proposed that antibiotics might help [11]. Good response to minocycline has been noted in many studies [3, 12–17] and is considered the treatment of choice. Minocycline was given for 1–3 months with a vast majority achieving complete clearance. Recurrence after stopping minocycline had been documented in some patients. It is believed that antibiotics mediate changes through their anti-inflammatory actions rather than antibacterial actions. In contrast, there is poor response to antifungals. Other beneficial medications include isotretinoin [18], topical tretinoin [19], topical tazarotene [20], calcipotriol [21], selenium sulphide [6], tacalcitol [22], and tacrolimus. Tinea versicolour will sometimes co-exist with the condition and potassium hydroxide preparation can be helpful in identifying patients who would benefit from topical antifungal therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree