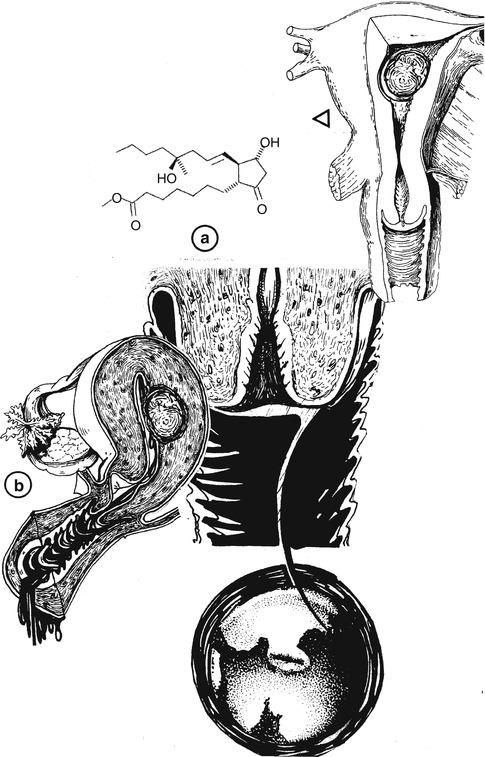

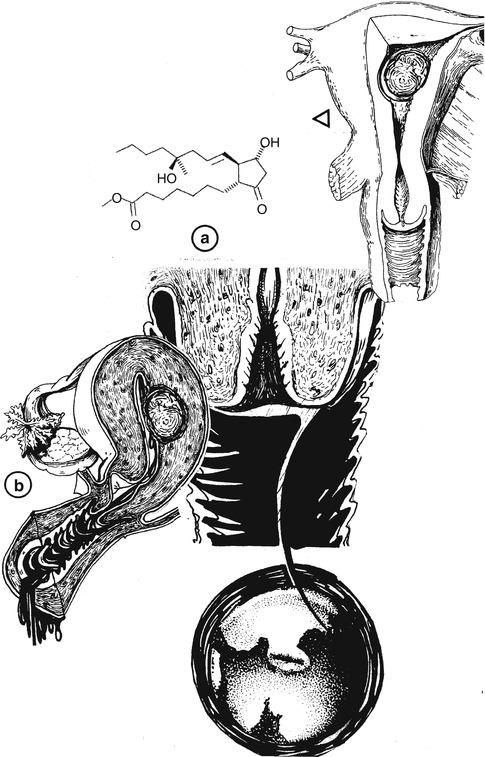

Fig. 17.1

(a) Transvaginal longitudinal ultrasonographic uterine scan with submucous myoma located in posterior uterine wall. (b) Preoperative transvaginal ultrasonographic scan showing fundal and corporal myomas

The common advice is to perform hysteroscopic myomectomy during the early proliferative phase of a cycle; however, some of these patients bleed nearly every day and some are anovulatory, so timing can be a problem. In addition, work, school, and personal activities are also factors in scheduling surgery. It is critical that one must be able to do hysteroscopic myomectomy anytime during the menstrual cycle because nature does not always cooperate.

The preoperative exam will make the gynecologist aware of cervical stenosis (Fig. 17.2) which can make uterine entry difficult, resulting in cervical lacerations or uterine perforation.

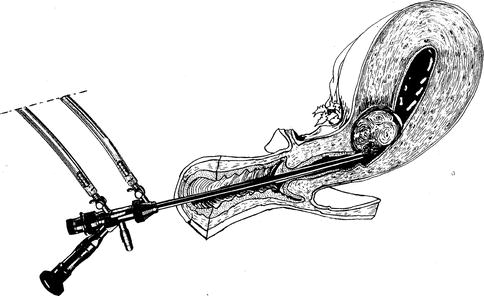

Fig. 17.2

A difficult operative hysteroscopy to remove a cervical-isthmic myoma for a stenotic uterine cervix

A 2–4 mm diameter Laminaria japonica can be inserted into the cervical canal on the day prior to surgery. This will usually dilate the cervix enough to allow intraoperative dilation and insertion of hysteroscopic instrumentation. The easier method is the administration of 400 μg of oral Misoprostol 12–24 h prior to surgery [1].

Vaginal administration of 400 μg of Misoprostol has also been shown to adequately soften and dilate the cervix [2].

The author has had the patient insert 200 mcg of Misoprostol intravaginal 8–10 h prior to surgery with excellent results (Fig. 17.3).

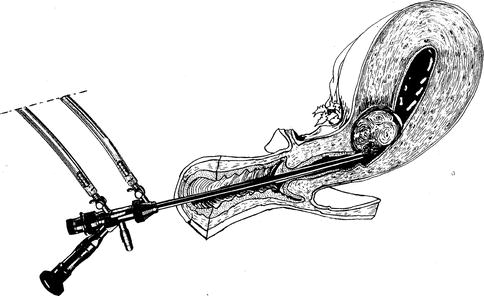

Fig. 17.3

Preoperative examination of stenotic uterine cervix (b) prior to hysteroscopic myomectomy, where it is suggested the use of misoprostol at 200 mcg (a) to stimulate cervical dilatation

Cervical Laceration

If a cervical laceration occurs in spite of the above techniques, it will either be from the tenaculum on the external cervix or from cervical dilation resulting in laceration of the endocervical canal or cervical-uterine junction. Both types of lacerations are the result of excess force while inserting the hysteroscope.

Besides the Laminaria or Misoprostol, 4 units of Vasopressin injected into the cervix has been shown to significantly reduce the force required to dilate the cervix [3].

The author has utilized 2 units of Pitressin in 10 cc saline with similar results and has noted a decrease in bleeding from the tenaculum and injection sites.

The external cervical lacerations are easily treated with interrupted or figure of eight absorbable suture. Lacerations of the endocervical canal are more concerning than external lacerations. Heavy bleeding and excess fluid can occur with lacerations of the cervical canal.

If the laceration is at the cervical-uterine junction, one can insert a Foley catheter into the uterine cavity (Fig. 17.4). The balloon is filled with 10–15 cc saline and pulled against the junction to act as a tamponade and also a drain to monitor the bleeding. If bleeding continues, one must suture the cervical branches of the uterine artery and if bleeding still does not stop, a hysterectomy may be the only option [4].

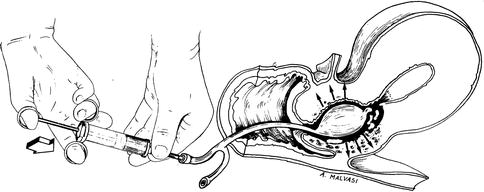

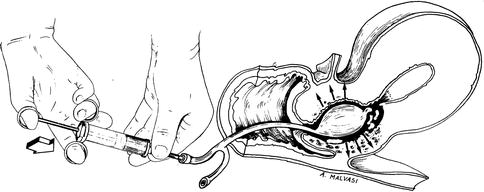

Fig. 17.4

A Foley catheter using after cervical laceration during hysteroscopic myomectomy to stop bleeding

Uterine Perforation

Uterine perforation occurs in approximately 1–2 % of all hysteroscopic procedures [5, 6] and 2–3 % in hysteroscopic myomectomies [7, 8].

Perforation with sound, dilator, hysteroscope (Fig. 17.5), without instrumentation or energy, usually just requires cessation of the procedure and observation.

Fig. 17.5

Uterine perforation of posterior wall and bowel loop, adherent to uterus, during hysteroscopic myomectomy

Serious complications are unlikely and complete blood count in 24 h is usually all that is needed. An ultrasound may also be performed. If there are signs of peritonitis, bowel injury must be ruled out by laparoscopy or laparotomy [4].

If perforation occurs with scissors, forceps, or active electrode, the risk to intra-abdominal structures is much more likely and laparoscopy or laparotomy should be seriously considered [9].

The author advises initial uterine entry under direct visualization with a hysteroscope to dilate the cervix and evaluate the uterine cavity.

Once the hysteroscope has been inserted and removed, the resectoscope or morcellator can often be inserted without the need for use of dilators. It should be noted that the preoperative ultrasound and saline infusion sonogram will document fibroid depth, and thus one can avoid resecting a transmural myoma. Simultaneous ultrasound monitoring may be helpful whenever a hysteroscopic myomectomy is anticipated in which a significant intramural component is present [10].

The author has utilized the preoperative ultrasound to measure the distance from the leiomyoma to serosa (Fig. 17.6).

Fig. 17.6

The measurement of distance between subserosal myoma and uterine serosa before hysteroscopic myomectomy

If there is at least 3 mm of myometrium, a partial myomectomy is performed.

The patient is then brought back for a repeat procedure and the leiomyoma has usually migrated significantly into the uterine cavity and can be easily resected in its entirety.

Fluid Intravasation

Fluid intravasation is a most serious but easily avoided complication if one pays meticulous attention to inflow and outflow volumes. There are several fluid pumps available. It is important that the gynecologist be familiar with that pump and also have the assistant in the room report the deficit at frequent intervals. If mechanical or bipolar resectoscope is being used, the distention media of choice is normal saline.

One should work at the lowest flow and pressure that still provides good visualization. In general, a deficit of 2,000 ml of saline is considered the maximal amount allowed. Once intravasation of saline goes over 2,000 ml, 20 mg of intravenous furosemide should be given, serum electrolytes drawn, and the procedure ended [11].

The margin of safety for fluid intravasation of nonconductive media used with the monopolar resectoscope is much less than that allowed with saline. The reason is that in healthy women, saline overload is easily managed with a diuretic; however, nonconductive fluid overload results in hyponatremia which has much more serious consequences.

Depending on the level of hyponatremia, manifestations include headache, restlessness, vomiting, confusion, cyanosis, arrhythmia, seizures, cerebral edema, brain herniation, and death. Thus, immediate treatment is necessary.

Limits for non-conductive media intravasation are generally 750–1,200 ml.

Obviously, women with medical problems should have lower limits for both conductive and non-conductive media.

An equation developed by Wortman has been used to calculate maximum allowable fluid absorption limit (MAFA limit) for nonconductive media.

In addition, he has developed excellent guidelines for management of hyponatremia [4].

This equation is for a healthy woman without cardiac, liver, or renal disease. Under no circumstances should a MAFA limit be more than 2 L since few data points are available for women weighing over 125 kg.

This equation is for a healthy woman without cardiac, liver, or renal disease. Under no circumstances should a MAFA limit be more than 2 L since few data points are available for women weighing over 125 kg.

With serum sodium concentrations between 130 and 140 mEq/L, no treatment is needed.

With serum sodium concentrations absent signs or symptoms of encephalopathy, fluid restriction and furosemide can be utilized for management.

An intensivist should be consulted for any serum sodium concentration below 120 mEq/L or if any evidence of encephalopathy regardless of serum sodium concentration.

Bleeding

Most bleeding stops shortly after the procedure is ended.

If bleeding persists, tamponade can be achieved by inserting a Foley catheter with 10–15 cc saline in the balloon and the tip of the catheter cut off. This procedure works nearly all the time.

In addition, 0.2 mg Methergine can also be given IM.

If this fails, one must consider uterine artery embolization, uterine artery ligation or hysterectomy.

Before one resorts to the three above measures, a second examination of the uterine cavity should be performed in the event that a single bleeding site can be coagulated. One must be very cautious when resecting leiomyomata in the lateral lower uterine segment, as this is where the larger vessels enter the uterus.

This is why mapping the location of the leiomyomata by ultrasound and saline infusion sonogram prior to surgery is important.

Gas Embolism

Although usually asymptomatic, gas embolism occurs frequently with use of the resectoscope in hysteroscopic surgery. The gas embolism should be differentiated from air embolism which is more likely to be serious and even fatal. Air embolism probably occurs from not purging room air out of the inflow line and is easily avoided by making sure the distention fluid has run completely through the inflow line before inserting the scope into the cervical canal.

Gas embolism, on the other hand, occurs from the effect of monopolar or bipolar electrical energy on tissue and distention media. The major components of electro-surgical gases generated by both bipolar and monopolar electrosurgery are hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide [15].

The amounts of generated gases are relatively equal in both bipolar and monopolar electrosurgery with increasing amounts related to increasing power.

An early sign of gas embolism is a drop in end–tidal CO2 or drop in oxygen saturation (Fig. 17.7).

Fig. 17.7

Pulmunar embolism during hysteroscopic myomectomy (e embolism, P.I. pulmonary ischemia)

Management involves early recognition and interruption of gas to open venous channels.

This involves immediately removing the resectoscope.

The problem is usually self limiting and once the patient stabilizes, the procedure is ended.

The easiest way to reduce the risk of gas embolism is to operate at the lowest intrauterine pressure possible and at the lowest effective power [16].

Infection

Infection is relatively uncommon with hysteroscopic myomectomy with a rate of 0.4 % reported in a collection of over 1,000 cases [17] (Fig. 17.8).

Fig. 17.8

Infections during hysteroscopic myomectomy (a); Asherman syndrome after hysteroscopic myomectomy

The author recommends prophylactic antibiotics for hysteroscopic myomectomy.

Adhesions

Adhesion formations following myomectomy in infertility patients are managed by a second look procedure 4–5 weeks after completion of myomectomy.

Complications of Laparoscopic Myomectomy

Laparoscopic myomectomy (Fig. 17.9) offers the same advantages over laparotomic myomectomy, namely quicker recovery decreased blood loss and less pain in the immediate post operative period. These benefits are weighed against the suggestion that closure of the myometrial defect and control of intraoperative bleeding is more difficult using a laparoscopic approach. Multiple retrospective studies have evaluated the outcomes and complications of myomectomy either performed laparoscopically or via laparotomy and they are the same [18].

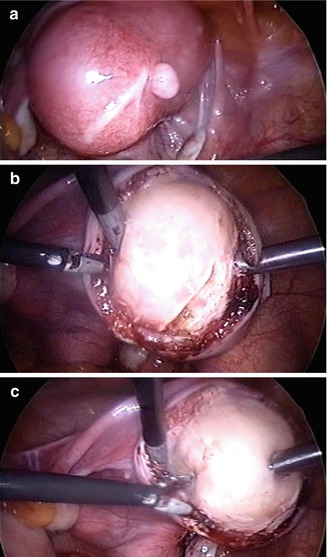

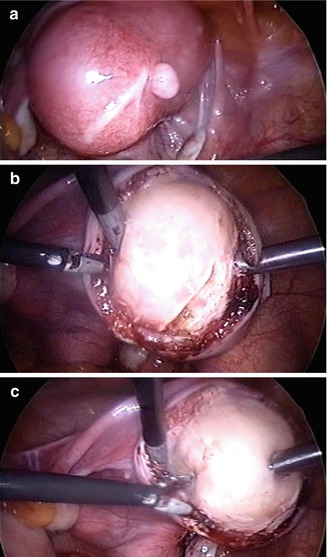

Fig. 17.9

A laparoscopic myomectomy: (a) incision of uterine serosa; (b) delicate dissection of myoma from its myoma pseudocapsule; (c) enucleation of myoma

Some of these complications are inherent to the procedure and may occur regardless of operative approach. The most described major complications are intraoperative hemorrhage, uterine hematomas, uterine rupture, undiagnosed sarcomas, bowel or ureteral damage, adenomyosis and leiomyomatosis.

The more commonly experienced minor complications are urinary tract infections and transient postoperative fever. All of these complications will be discussed in this chapter as well as suggestions to prevent them from occurring.

Laparoscopic Myomectomy

Inherent in any laparoscopic procedures are the potential risks associated with laparoscopy itself. The risks and complications are related to abdominal entry and placement of operating ports. The addition of a large uterus irregularly shaped by multiple fibroids will distort and compromise the capacity of the abdominal cavity.

Insufflation and visualization of the abdomen can be safely accomplished with the use of a left upper quadrant port placed at Palmer’s point (Fig. 17.10).

Fig. 17.10

Insufflation and visualization of the abdomen can be safely accomplished with the use of a left upper quadrant port placed at Palmer’s point

This vantage point not only prevents damage to the great vessels and bowel during initial entry but allows the surgeon to visually gauge where the operating and laparoscopic ports should be placed in relation to the myomatous uterus (Fig. 17.11).

Fig. 17.11

The surgeons and laparoscopic ports should be placed in relation to the myomatous uterus

Visualizing the anatomical path of the inferior epigastic vessels before lateral port placement and introducing the lateral ports, perpendicular to the abdominal wall prevent vessel laceration (Fig. 17.12).

Fig. 17.12

Perpendicular introduction of accessory port avoiding the inferior epigastric vessels

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree