Clinical Guidelines for Contraception at Different Ages: Early and Late

Modern society is coping with two contraceptive problems, each at the opposite end of the reproductive lifespan. In the early years, we are struggling with the high rate of unwanted teenage pregnancies. In the later years, we face a growing demand for reversible contraception as a lingering impact of the post-World War II baby boom, with deferment of marriage and postponement of pregnancy in marriage accounting for a major social change. It is entirely appropriate, therefore, that we give special attention to these age groups: adolescence and the transition years (ages 35 to menopause).

Nearly half of all pregnancies (49%) in the United States are unplanned, and about 40% of these are aborted.1,2 American teenagers abort about 34% of their pregnancies, and this proportion is similar to that seen in other countries.3 But older American women, aged 20 to 34, have the highest proportion of pregnancies aborted compared with other countries, indicating an unappreciated, but real, problem of unintended pregnancy existing beyond the teenage years. In fact, American women older than age 40 have had for the last 2 decades a high ratio of abortions per live births, a ratio very similar to that of teenagers.4

Contraception for Adolescents

Providing contraception or information about contraception for young people under age 20 is an important obligation for clinicians. More young women (about 750,000 teenagers per year) become pregnant in the United States than do their contemporaries in other developed parts of the world, and young American women have a higher induced abortion rate than young European women.2,3 The differences among developed countries (and the unenviable highest teenage pregnancy rates in the United States) are not the consequence of differences in sexual activity, but reflect effective sex education programs combined with easy access to contraception.

About 82% of all pregnancies among American teenagers are unintended.2 Increasing effective contraceptive use among young Americans began to have an impact in 1991. In the 1990s, the teenage pregnancy rate reached the lowest rate since estimates began in 1976, a 21% decline from 1991 to

1997 for teenagers 15 to 17 years and a 13% decline for older teenagers.5 Overall, there was a 17% decline in teenage birth rates and a 12.8% decline in teenage induced abortions from 1991 through 1999. From 1995 to 2002, 14% of the decline in teen pregnancy was a consequence of decreased sexual activity among U.S. teenagers; however, 86% of the decline was attributed to an increase in the use of effective contraception.6

1997 for teenagers 15 to 17 years and a 13% decline for older teenagers.5 Overall, there was a 17% decline in teenage birth rates and a 12.8% decline in teenage induced abortions from 1991 through 1999. From 1995 to 2002, 14% of the decline in teen pregnancy was a consequence of decreased sexual activity among U.S. teenagers; however, 86% of the decline was attributed to an increase in the use of effective contraception.6

In 2004, the proportion of induced abortions in the United States obtained by teens reached a low of 17%.4 However, after a 14-year 34% decline, birth rates for teenagers began to increase in 2005, the first increase since 1991. The rate increased 5% between 2005 and 2008.7 There is appropriate concern that this increase reflects difficulties in contraceptive access, affordability, and correct use. In addition, in recent years, fewer teens have received instruction regarding contraception.3,8

Delaying marriage prolongs the period in which women are exposed to the risk of unintended pregnancy. This, however, cannot be documented as a major reason for the large differential between young adults in Europe and the United States. The available evidence also indicates that a difference in sexual activity is not an important explanation. The major difference between American women and European women is that American women under age 25 are less likely to use any form of contraception. Significantly, the use of oral contraceptives (the main choice of younger women) is lower in the United States than in other countries.

There was a marked increase in teenage sexual activity in the United States during the time period 1960 to 1990, and contrary to common opinion, much of that increase occurred among white and nonpoor adolescents.9 Today, approximately 60% of young women and 70% of young men have had sexual intercourse by age 18.3,10 Within a relatively short period of time after becoming sexually active, 58% of adolescent females have had sex with two or more partners (and thus, increase their risk of sexually transmitted infections, STIs). The good news is that the use of oral contraceptives and condoms increased in the 1990s; however, teenagers are nearly twice as likely to experience contraceptive failure than women age 30 years or more.11

Adolescents who have a much older partner (about 7% of women younger than age 18 have a partner 6 or more years older) represent a very high risk group, with a low rate of contraceptive use and high rates of pregnancy.12 Unfortunately, adolescent mothers have a high rate of repeat pregnancy and are more likely to use ineffective methods and to use effective methods inconsistently.

Characteristics of Teen Pregnancy in the United States3,13,14,15,16,17

1. Half of teen pregnancies occur in the first 6 months after first intercourse.

2. 20% of teen pregnancies occur in the first month after first intercourse.

3. Half who give birth do not graduate from high school.

4. Teen pregnancies are associated with increased risks of obstetrical and neonatal complications and mortality.

5. The children of teen mothers are more likely to have behavioral and social problems when they are adolescents.

Adolescence is a time for “trying your wings,” a time for experimenting and testing. Most of the 28 million teenagers in the United States will achieve good health, but unfortunately for some, the consequences of this time of trying things will be lasting problems for health and life. Unwanted pregnancy (premature parenthood) and the STIs are the risks of sexual experimentation. Teenage girls carry the burdens of unprotected sexual activity: unwanted pregnancy, undetected STIs, and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Their male partners, who are often not themselves teenagers, must be made aware of these consequences through public education that reaches all young people, not just those in school, and through social programs that promote male responsibility for child support and disease prevention.

Teenagers are noted for their sense of invincibility and their risk-taking behavior, both of which denote the inability of immature people to connect present action with future consequences. It is not surprising that adolescents often have sex and do not use contraception. Contraception takes planning and premeditation about having sex, but television and movies present teenagers with unrealistic examples of romantic liaisons that disconnect sex from pregnancy, STIs, and contraception. About half of female teenagers have risked pregnancy, infertility, and AIDS by having unprotected intercourse at least once.3 The onset of fertility following menarche cannot be predicted for individuals; any sexually active teenager is at risk for pregnancy, as well as STIs. Approximately 48% of the new STI cases in the United States occur in the 15 to 24 age group, a group that accounts for only 25% of the sexually active population.18 It is worth emphasizing that there is no evidence that provision of contraception leads to adolescents having sex earlier or more frequently.

The majority of teenagers, but not all, now use contraceptives, usually the condom, the first time they have sex.3 About one-third of condom users in 2002 were using more than one method, especially younger and never married women, including use of an oral contraceptive and a condom in 14% at first intercourse! Once teenagers begin the use of contraception, many are persistent users; 83% of teen females and 91% of teen males now report using contraception at their most recent sex experience, a marked improvement since 1995.3

Among the obstacles to earlier use of contraception are exaggerated perceptions about the risks of contraceptive methods, as well as a deep dread of the misunderstood “pelvic exam.”19 We clinicians can do much to remove these obstacles by talking with teenagers and adjusting our practices to suit their special needs.

Our objective is to get adolescents to realistically assess their sexual futures, not to just let sex “happen.” The fact that European adolescents use

contraception at a rate higher than in the United States argues that we can do better. Unfortunately, secrecy usually surrounds a young person’s decision to use contraception. Adolescent involvement in sex often occurs without an opportunity for discussion with family, other adults, peers, or even the partner. Access to contraception (physical and psychological) and motivation to use it are the keys to success in achieving our goals. Good communication with adolescents requires specific approaches and skills. Greater openness about sexual discussion in the family, church, or school can all lead to a better consideration of the health and social risks of early sexual activity by a teenager. Contraceptive education must be combined with an emphasis on overall life issues and interventions, including the decision to become sexually active; no single message or approach, by itself, will be broadly effective for all adolescents.

contraception at a rate higher than in the United States argues that we can do better. Unfortunately, secrecy usually surrounds a young person’s decision to use contraception. Adolescent involvement in sex often occurs without an opportunity for discussion with family, other adults, peers, or even the partner. Access to contraception (physical and psychological) and motivation to use it are the keys to success in achieving our goals. Good communication with adolescents requires specific approaches and skills. Greater openness about sexual discussion in the family, church, or school can all lead to a better consideration of the health and social risks of early sexual activity by a teenager. Contraceptive education must be combined with an emphasis on overall life issues and interventions, including the decision to become sexually active; no single message or approach, by itself, will be broadly effective for all adolescents.

School-Based Programs

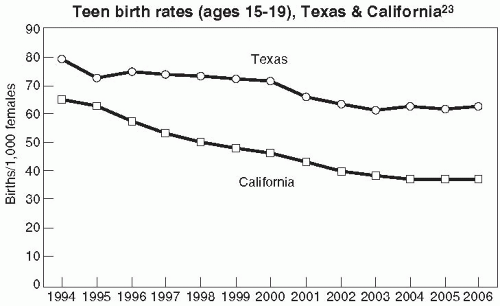

Many school-based (or school-linked) educational programs and clinics have been developed to prevent adolescent pregnancies. These vary in focus and content, including abstinence and contraception. Reviews of school-based programs have concluded that a focus on abstinence is ineffective.20,21,22 Thirty-five percent of all school districts in the United States allow only the teaching of abstinence, and 86% teach abstinence as the preferred method of contraception (these percentages are increases over the past decade).3 Although most school districts provide some contraceptive education (a development of the 1990s), approximately 33% of public school districts do not have a policy to teach sex education.3 Current information on state policies is available at: www.guttmacher.org/. Note in the figure the marked difference in teen birth rates in Texas and California, a difference that reflects the acceptance by Texas of federal funding that required unbalanced teaching featuring abstinence and the refusal of such funding by California.

Teen birth rates (ages 15-19), Texas & California23 |

The evidence overwhelmingly indicates that abstinence programs have not had a positive impact on teen sexual behavior, including the delay of the initiation of sex or the number of sexual partners.24 In contrast, comprehensive sex education programs that include contraception are effective and do not increase the frequency of sex or hasten the initiation.25

Fortunately, 86% of U.S. students live in districts that have a sex education policy, and even in those districts without a policy, individual schools and teachers can provide sex education. An emphasis on education is very important because although school clinics by themselves do not lower pregnancy rates, an associated community educational effort is effective.20,26,27 A comprehensive community-wide program that includes school interventions, public education, and emphasis of both abstinence and contraception results in a reduction of the teenage pregnancy rate.28,29,30 To again counter a common criticism, school-based programs and clinics do not affect the initiation or frequency of sexual activity.3,20,27,31

An analysis of data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth concluded that formal sex education before the initiation of sexual experiences postpones sexual intercourse and increases the use of contraception, especially among adolescents at high risk for early sex and STIs.25

Communication with Adolescents

Teenagers want to talk about STIs and contraception, but clinicians usually do not bring these subjects up for discussion.32 Clinicians can be sure that by age 15 most adolescents will be interested in discussing STIs and contraception. No matter what brings an adolescent into the office, contraception and continuation (compliance) are issues that should be addressed. Unfortunately, the younger a teenager is the more likely it is that she believes an unwanted pregnancy or STI cannot happen to her.33

Our goals are to promote abstinence among teenagers who are not yet ready to cope with sex and its consequences and to promote behavior that will prevent pregnancy and STIs in sexually active adolescents. Building trust is a requirement for a successful interaction between clinician and adolescent. A teenager must be assured that a discussion about sexuality and contraception will be strictly confidential. This must be stated in plain words. One reason European countries are able to provide better contraceptive services to adolescents is the guarantee by law of complete confidentiality (other reasons are dissemination of information via public media and distribution of contraceptives through free or low-cost services).34 Research confirms that requiring parental notification or consent deters young people from using contraception and protecting themselves from STIs.35 That is not to say that secrecy is encouraged; rather, communication with parents should be promoted because it yields better use of contraception. However, the clinician must receive permission from the adolescent for parental involvement.

Successful use of contraception (continuation) requires teenager involvement, not just passive listening. The clinician should frequently interrupt talking by asking questions and seeking opinions. Do not wait until the physical examination to initiate conversation. It is a good practice to see all patients first in an office setting prior to examination, and this is especially true with adolescents. Give some thought to body language and position. It is helpful to sit next to a patient; avoid the formality (and obstacle) of a desk between clinician and patient. A teenager should be asked about success in school, family life, and behaviors indicative of risk taking.

Do not miss the chance to point out the wisdom of abstinence to a young person who is not yet sexually active, but leave the door open for protection against pregnancy and STIs. Be careful to be nonjudgmental. Sometimes, it is hard to keep disapproval over a teenager’s activity from showing. A teenager who senses disapproval will not listen to instructions or advice.

A good way to introduce the subject of contraception is to ask an adolescent when he or she would like to have children. Then follow with: what plans do you have to avoid getting pregnant until then? Elicit objections, concerns, fears, and address each of them. The clinician must anticipate those concerns and fears that will lead to poor continuation. They must be identified and addressed in advance.

Contraceptive use is a private matter, and therefore, instruction comes from the clinician, not from peers. Be very concrete; demonstrate the use of pill packages, the skin patch, the vaginal ring, foam aerosols, and condom application. This seems like oversimplification, but clinicians working with adolescents have found that this approach is both necessary and appreciated by their young patients. If possible, family involvement that results in improved emotional support of a teenager is worthwhile because it is associated with better contraceptive behavior.36

Adolescents must be convinced that having sex means you are at risk of becoming pregnant. Adolescents are immersed in conflicting messages about sexuality in our society. A clinician may be the only resource for information and guidance, but clinicians must give the right signals to adolescents and must initiate communication. No matter what the chief complaint, any interaction with an adolescent is an opportunity to discuss sexuality and contraception.

Useful Web Sites for Adolescents and Clinicians

Center for Young Women’s Health, Children’s Hospital, Boston: http://youngwomenshealth.org

Planned Parenthood: http://Teenwire.com/index.asp

Columbia University Health Education Program: http://www.goaskalice.columbia.edu/

Princeton University Emergency Contraception Site: http://ec.princeton.edu

Choice of Method Oral, Vaginal, and Transdermal Estrogen-Progestin Contraception

The combined oral contraceptive is the most popular and most requested method of contraception by teenagers.37 This is appropriate because oral contraceptives are almost never medically contraindicated in healthy adolescents. The risk of death from oral contraceptive use by adolescents is virtually nil. This is a good match; adolescents are at highest risk for unwanted pregnancies and are at lowest risk for complications. Thus, the high efficacy of combined oral contraception is an excellent choice for teenagers.

Adolescents certainly do not know the history of oral contraception. It is important to point out the change in dosage and the new safety. But teenagers do have concerns regarding oral contraception, citing most often a fear of cancer, concern with impact on future fertility, and problems with weight gain and acne.38

The cancer issue is a difficult one to discuss with teenagers. We believe it is appropriate to state that there is no definitive evidence demonstrating a link between breast cancer and oral contraception, as discussed in Chapter 2. Cervical cancer, especially adenocarcinoma, continues to be a concern (Chapter 2), although confounding factors have been difficult to control. Teens must be made aware that Pap smear surveillance will detect premalignant conditions.

By the time of menarche, growth and reproductive development are essentially complete. There is no evidence that early use of oral contraception has any inhibiting impact on growth or any adverse effects on the reproductive tract. With great confidence, a clinician can tell adolescents that there is no impact on future fertility with the use of oral contraception.39 Indeed, one can emphasize that oral contraception preserves future fertility by its protection against PID and ectopic pregnancies. Whereas oral contraception protects against PID, it does not protect against contracting STIs, hence the recommendation to combine oral contraception use with barrier methods. Because younger women change partners more frequently than older women, a dual approach is recommended, combining the contraceptive efficacy offered by oral contraceptives with the use of a barrier method, especially for teenagers, so that they can prevent PID and viral STIs, including HIV.

It is worth emphasizing repeatedly to adolescents that studies with lowdose oral contraception,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47 even studies in adolescents,40 do not indicate a problem of weight gain, and that acne is usually improved. Weight gain as it is perceived by the teenager deserves attention at every visit.48 In placebocontrolled randomized trials of low-dose oral contraceptives and acne, the incidence of weight gain was identical in both the treated and the placebo groups.45,47 The beneficial impact of oral contraceptives on acne can be especially motivating for adolescents.

Adolescents are very receptive to hearing about the beneficial impact of oral contraception on menstrual problems: cramps, bleeding, and irondeficiency anemia. Relief of dysmenorrhea in teenagers has been documented to be associated with better and more consistent use of oral contraceptives.49 Although irregular bleeding on oral contraceptives can distress teenagers, it will not by itself cause improper use if teenagers are well prepared and instructed.

Steroid Contraceptive Benefits to Emphasize with Teenagers

Safety with low dosage.

Lack of weight gain.

Acne improvement and prevention.

Reduction in menstrual flow and dysmenorrhea.

Preservation of fertility.

Reduced risk of PID.

Although decreasing in prevalence, teenage smoking continues to be a big problem. Currently, approximately 35% of people in the United States who have not obtained a high school diploma are smokers, but only 12% of those with higher education. Approximately 23% of men and 18% of women are smokers.50 Cigarette smoking among high school students peaked in 1997 and then declined to the current level of 20%.50 In addition, 14% of high school students smoke cigars and 8% use chewing tobacco. Smoking initiation has decreased markedly in men, but unfortunately has changed less in women. In addition, female smokers begin smoking at a younger age. It is important to note that smoking appears to have a greater adverse effect on women compared to men.51,52 Women who smoke only one to four cigarettes per day have a 2.5-fold increased risk of fatal coronary heart disease.53

The relative risk of cardiovascular events is increased for women of all ages who smoke and use oral contraceptives. However, because the actual incidence of cardiovascular events is so low at a young age, the real risk is very, very low for young women. Smoking produces a shift to hypercoagu-lability.54 A 20-µg estrogen formulation has been reported to have no effect on clotting parameters, even in smokers.54,55 One study comparing a 20-µg product with a 30-µg product found similar mild procoagulant and fibrinolytic activity, although there was a trend toward increased fibrinolytic activity with the lower dose.56 It is worth considering a 20-µg formulation for all smoking women, regardless of age. This recommendation also applies to all women using nicotine-containing products as an aid to stop smoking.

Adolescents with diabetes mellitus uncomplicated with vascular changes can use oral contraception. Other conditions with which oral contraception is acceptable include cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, or inactive, stable, moderate systemic lupus erythematosus with a low risk for thrombosis.

Unfortunately, the failure rate of oral contraceptives among adolescents is higher compared with all typical users.11 This is the reason that adolescents require special attention at every opportunity. Education and support

are necessary to maximize efficacy and continuation. Serial monogamy is usual among younger women, and this often is associated with episodic use of contraception. With oral contraception, it is helpful to instruct the adolescent that the minor side effects diminish in frequency with use, and therefore, there is an advantage to staying on the oral contraceptive. It is also good advice to tell teenagers to continue taking oral contraceptives for at least 2 months after “breaking up” with a boyfriend, because by then a new relationship is likely to have begun.

are necessary to maximize efficacy and continuation. Serial monogamy is usual among younger women, and this often is associated with episodic use of contraception. With oral contraception, it is helpful to instruct the adolescent that the minor side effects diminish in frequency with use, and therefore, there is an advantage to staying on the oral contraceptive. It is also good advice to tell teenagers to continue taking oral contraceptives for at least 2 months after “breaking up” with a boyfriend, because by then a new relationship is likely to have begun.

One reason the average teenager waits months to a year after initiating sexual activity before seeking contraception is fear about the pelvic exam. Furthermore, anxiety over the pelvic exam is a barrier to comprehending contraceptive instructions. Thus, letting teenagers know that the pelvic exam can be delayed until the third or sixth month or even later will encourage them to seek contraceptive advice. This approach requires a completely normal history (an absence of risk factors for STIs) and a limited prescription. We advocate the elimination of pelvic and breast examinations as a requirement for teenagers to obtain contraceptives. Demonstration projects have indicated that this approach is safe and effective.57,58

We believe that the risks, benefits, and considerations associated with oral contraception will be similar for the vaginal and transdermal estrogenprogestin contraceptive methods. However, the contraceptive patch (Ortho-Evra) and the vaginal ring (NuvaRing) have an important advantage. Avoiding the necessity of daily pill-taking yields better compliance rates (Chapter 4).59,60,61,62 Adolescents have used the transdermal contraceptive patch with good compliance, but difficulties with patch detachments underscore the need for good instruction (see Chapter 4).63

Barrier Methods

Teenagers have the highest rates of STIs and hospitalization for PID. Because of the following statistics cited about adolescent women, sexually active young women should be examined every 6 months, with Pap smear and STI screening64,65,66,67:

1. 26% of female adolescents (about 3.2 million) have at least one of the STIs.

2. 3.9% of sexually active adolescent females are infected with Chlamydia trachomatis.

3. 18.3% have human papillomavirus infection.

4. 16% of adolescents have abnormal Pap smears.

For these reasons, combined with the AIDS scare, there has been an increase in the use of condoms among adolescents. After steroid contraception, in our view, the condom is the next best choice for adolescents. And this obviously is the only choice for male adolescents. Indeed, we strongly advocate combining condoms with oral contraception to provide maximum protection against pregnancy and STIs. Approximately one-third of American adolescent women do combine condom use with another method.37

The advantage of condoms is that neither a prescription nor a consultation with a clinician is required. The problem, then, is achieving sufficient education and motivation without the intervention of clinicians. We believe this is a social problem, not a medical problem, and we are strongly supportive of public education efforts in schools and the media to accomplish this important public and individual health objective.

Many teenagers rely only on condoms (a close second in use to oral contraceptives), and of course their contribution to preventing STIs is important.37 Indeed, among the youngest teenagers, condoms are the most commonly used method of contraception.37 Condom failures, unfortunately, are about 10 times as high among teenagers as among older, married couples. Do not assume that teenagers know how to use a condom; use a model and demonstrate. Furthermore, young women need to know that they are in charge; they can insist on condom use.

The female condom provides a young woman with a female-controlled method, but its expense and complexity are obstacles for teenagers. Its use by teenagers has not been studied, and its effects on STIs are not documented.

Diaphragms or cervical caps are not good choices for adolescents. Adolescents are not comfortable with body interventions, and the insertion before coitus is too willful an act for most teens. Furthermore, these methods require privacy for insertion. Adolescents are discouraged by complicated methods. The diaphragm and cervical cap should be reserved for very motivated and mature young people.

Intrauterine Contraception

Traditionally, intrauterine devices (IUDs) have not been recommended for nulligravid women and those who have a high risk of STIs. This eliminated it from consideration for most teenagers. However, we wish to emphasize that age and parity are not the critical factors; the risk for STIs is the most important consideration. The IUD does not increase a teenager’s risk of STIs nor does it affect future fertility. The IUD is a good choice for the appropriate patient as described in Chapter 7, regardless of age. The IUD can and should be considered for the appropriate nulligravid young woman, although increased menstrual pain and bleeding can be a problem.68 It is also a good choice in a patient with a chronic illness, such as diabetes mellitus or systemic lupus erythematosus, or in mentally retarded individuals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree