INTRODUCTION

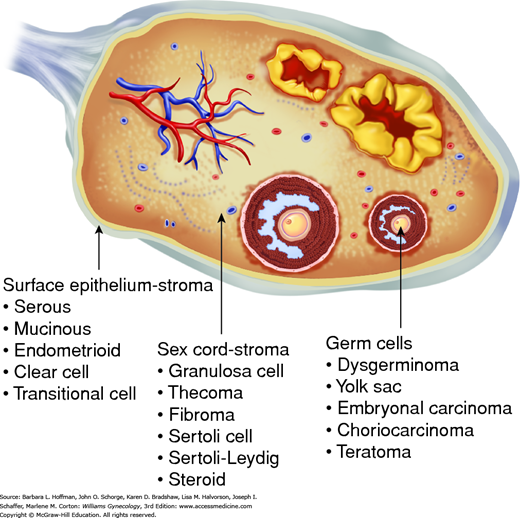

Three major categories account for virtually all malignant ovarian tumors. Organization of these groups is based on the anatomic structures from which the tumors originate (Fig. 36-1). Epithelial ovarian cancers account for 90 to 95 percent of malignant ovarian tumors (Chap. 35). Germ cell and sex cord-stromal ovarian tumors account for the remaining 5 to 10 percent and have unique qualities that require a special management approach (Quirk, 2005).

MALIGNANT OVARIAN GERM CELL TUMORS

Germ cell tumors arise from the ovary’s germinal elements and make up one third of all ovarian neoplasms. The mature cystic teratoma, also called dermoid cyst, is by far the most common subtype. This accounts for 95 percent of all germ cell tumors, is clinically benign, and discussed in Chapter 9. In contrast, malignant germ cell tumors compose 2 to 3 percent of malignant ovarian cancers in Western countries and include dysgerminoma, yolk sac tumor, immature teratoma, and other less common types.

Three features distinguish malignant germ cell tumors from epithelial ovarian cancers. First, individuals typically present at a younger age, usually in their teens or early 20s. Second, most have stage I disease at diagnosis. Third, prognosis is excellent—even for those with advanced disease—due to exquisite tumor chemosensitivity. Fertility-sparing surgery is the primary treatment for women seeking future pregnancy, although most will require postoperative chemotherapy.

The age-adjusted incidence rate of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors in the United States is much lower (0.4 per 100,000 women) than that of epithelial ovarian carcinomas (15.5) (Quirk, 2005). Smith and associates (2006) analyzed 1262 cases of malignant ovarian germ cell from 1973 to 2002 and observed that incidence rates have declined 10 percent during the past 30 years. Unlike a significant proportion of epithelial ovarian carcinomas, malignant germ cell tumors are not generally considered heritable, although rare familial cases are reported (Galani, 2005; Stettner, 1999).

These tumors are the most common ovarian malignancies diagnosed during childhood and adolescence, although only 1 percent of all ovarian cancers develop in these age groups. At age 20, however, the incidence of epithelial ovarian carcinoma begins to rise and exceeds that of germ cell tumors (Young, 2003).

The signs and symptoms associated with these tumors vary, but in general, most originate from tumor growth and the hormones they produce. Subacute abdominal pain is the presenting symptom in 85 percent of patients and reflects rapid growth of a large, unilateral tumor undergoing capsular distention, hemorrhage, or necrosis. In 10 percent of cases, cyst rupture, torsion, or intraperitoneal hemorrhage leads to an acute abdomen (Gershenson, 2007a). In more advanced disease, ascites may develop and cause abdominal distention. Because of the hormonal changes that frequently accompany these tumors, menses can become heavy or irregular. Although most individuals note one or more of these symptoms, one quarter of individuals are asymptomatic, and a pelvic mass is noted unexpectedly during physical or sonographic examination (Curtin, 1994).

Individuals typically seek care within 1 month of the onset of abdominal complaints, although some note subtle waxing and waning of symptoms for more than a year. Vague pelvic symptoms are common during adolescence due to initiation of ovulation and menstrual cramping. As a result, early symptoms may be missed. Moreover, girls may be silent about changes to their normal pattern, fearful of their significance. Most young women with these tumors are nulligravidas with normal periods, but as discussed later, dysgenetic gonads is a known risk factor for development of these tumors (Brown, 2014b). Therefore, adolescents who present with pelvic masses and delayed menarche should be evaluated for gonadal dysgenesis (Chap. 16).

Distinguishing physical findings are typically lacking in individuals with malignant germ cell tumors. A palpable mass on pelvic examination is the most common. In children and adolescents, however, completing a comprehensive pelvic or transvaginal sonographic examination can be difficult and can lead to diagnostic delay. Accordingly, premenarchal patients may require examination under anesthesia to adequately assess a suspected adnexal tumor. The remainder of the physical examination searches for signs of ascites, pleural effusion, and organomegaly.

In patients with a suspected malignant germ cell tumor, serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) tumor markers, complete blood count, and liver function tests are drawn before treatment. Alternatively, the appropriate tumor markers may be ordered in the operating room if the diagnosis was not previously suspected (Table 36-1). Preoperative karyotyping of young women with primary amenorrhea and a suspected germ cell tumor can clarify whether both ovaries should be removed, as in the case of individuals with gonadal dysgenesis (Hoepffner, 2005).

Early symptoms can be misinterpreted as those of pregnancy, and acute pain may be confused with appendicitis. Finding an adnexal mass is the first diagnostic step. In most cases, sonography can adequately display those qualities that typically characterize benign and malignant ovarian masses (Chap. 9). Functional ovarian cysts are vastly more common in young women. Once these hypoechoic smooth-walled cysts are identified by sonography, they may be observed. Mature cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts) usually display characteristic features when imaged with sonography or computed tomography (CT) (Chap. 9). In contrast, the appearance of malignant germ cell tumors differs, and a multilobulated complex ovarian mass is typical (Fig. 36-2). Moreover, prominent blood flow in the fibrovascular septa may be seen using color flow Doppler sonography and suggests the likelihood of malignancy (Kim, 1995). Additional preoperative CT or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging may be indicated based on clinical suspicion. Chest radiography is warranted upon diagnosis to search for tumor metastases in the lungs or mediastinum.

Surgical resection is generally required for definitive tissue diagnosis, staging, and treatment. The surgeon should request a frozen section analysis to confirm the diagnosis, but discrepancies between frozen section interpretations and the final paraffin histology are commonplace (Kusamura, 2000). In addition, specific immunostaining is often required to resolve equivocal cases (Cheng, 2004; Ramalingam, 2004; Ulbright, 2005). In contrast, a sonographically or CT-guided percutaneous biopsy has a very limited role in the management of select patients with an ovarian mass suspicious for malignancy.

Most patients will initially be seen by a generalist gynecologist. Initial symptoms may point to the more common functional ovarian cyst. Persistent symptoms or an enlarging pelvic mass, however, should prompt sonographic evaluation. If a complex ovarian mass with solid features is noted in this young age group, then measurement of serum hCG and AFP levels and referral to a gynecologic oncologist for primary surgical management should ensue.

If a specialist is unavailable or the diagnosis is not anticipated beforehand, intraoperative decision making is crucial to adequately treat the patient without compromising future fertility. Peritoneal washings are obtained and set aside before proceeding with dissection of any suspicious adnexal mass. These can be discarded later if malignancy is excluded. Initially, the decision to perform cystectomy or oophorectomy depends on the clinical circumstances (Chap. 9). In general, the entire adnexa should be removed once a malignant ovarian germ cell tumor is diagnosed. A generalist gynecologist should request intraoperative assistance with staging from a gynecologic oncologist or refer the patient postoperatively if a specialist is not immediately available. At minimum, the abdomen should be explored. Palpation of the omentum and upper abdomen and inspection of the pelvis—especially the contralateral ovary—is easy to perform and document.

The modified World Health Organization (WHO) classification of ovarian germ cell tumors is presented in Table 36-2. These tumors are composed of several histologically different tumor types derived from primordial germ cells of the embryonic gonad. There are two major categories: primitive malignant germ cell tumors (dysgerminomas) and teratomas, almost all of which are accounted for by mature cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts).

| Germ cell tumors |

| Dysgerminoma |

| Yolk sac tumor (endodermal sinus tumor) |

| Embryonal carcinoma |

| Nongestational choriocarcinoma |

| Mature teratoma |

| Solid |

| Cystic(dermoid cyst) |

| Immature teratoma |

| Mixed germ cell tumor |

| Monodermal teratoma and highly specialized types arising from a mature cystic teratoma |

| Thyroid tumors (struma ovarii: benign or malignant) |

| Carcinoids |

| Neuroectodermal tumors |

| Carcinomas (squamous cell or adeno-) |

| Sebaceous tumors |

Primitive germ cells migrate from the wall of the yolk sac to the gonadal ridge (Fig. 18-1). As a result, most germ cell tumors arise in the gonad. Rarely, these tumors may develop primarily in extragonadal sites such as the central nervous system, mediastinum, or retroperitoneum (Hsu, 2002).

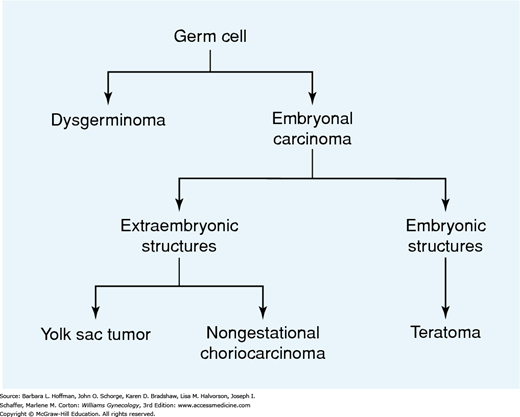

Ovarian germ cell tumors have a variable pattern of differentiation (Fig. 36-3). Dysgerminomas are primitive neoplasms that do not have the potential for further differentiation. Embryonal carcinomas are composed of multipotential cells that are capable of further differentiation. This lesion is the precursor of several other types of extraembryonic (yolk sac tumor, choriocarcinoma) or embryonic (teratoma) germ cell tumors. The process of differentiation is dynamic, and the resulting neoplasms may be composed of different elements that show various stages of development (Teilum, 1965).

Because their incidence has declined by approximately 30 percent over the past few decades, dysgerminomas currently account for only approximately one third of all malignant ovarian germ cell tumors (Chan, 2008; Smith, 2006). Dysgerminomas are the most common ovarian malignancy detected during pregnancy. This is believed to be an age-related coincidence, however, and not due to some particular characteristic of gestation.

Five percent of dysgerminomas are discovered in phenotypic females with karyotypically abnormal gonads, specifically, with the presence of a normal or abnormal Y-chromosome (Morimura, 1998). Commonly, this group includes those with Turner syndrome mosaicism (45,X/46,XY) and with Swyer syndrome (46,XY, pure gonadal dysgenesis) (Chap. 16). The dysgenetic gonads of these individuals often contain gonadoblastomas, which are benign germ cell neoplasms. These tumors may regress or alternatively may undergo malignant transformation, most commonly to dysgerminoma. Because approximately 40 percent of gonadoblastomas in these individuals undergo malignant transformation, both ovaries should be removed (Brown, 2014b; Hoepffner, 2005; Pena-Alonso, 2005).

Dysgerminomas are the only germ cell malignancy with a significant rate of bilateral ovarian involvement—15 to 20 percent. Half of patients with bilateral lesions will have grossly obvious disease, whereas cancer in the remainder will only be detected microscopically. Five percent of women have elevated serum hCG levels due to intermingled syncytiotrophoblast. Similarly, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and the isoenzymes LDH-1 and LDH-2 may also be useful in monitoring individuals for disease recurrence (Pressley, 1992; Schwartz, 1988).

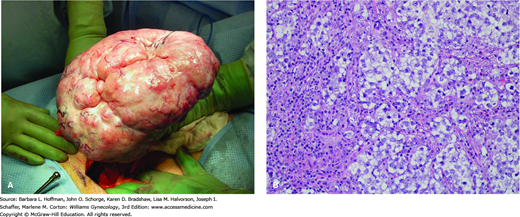

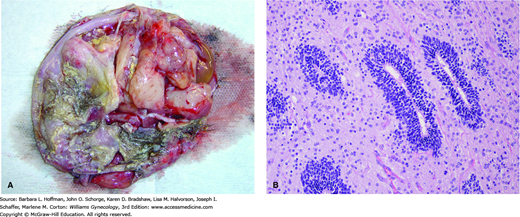

Dysgerminomas have a variable gross appearance, but in general are solid, pink to tan to cream-colored lobulated masses (Fig. 36-4). Microscopically, there is a monotonous proliferation of large, rounded, polyhedral clear cells that are rich in cytoplasmic glycogen and contain uniform central nuclei with one or a few prominent nucleoli. The tumor cells closely resemble the primordial germ cells of the embryo and are histologically identical to seminoma of the testis.

FIGURE 36-4

Dysgerminoma. A. Intraoperative photograph. B. Dysgerminoma is characterized microscopically by a relatively monotonous population of cells resembling primordial germ cells, with a central rounded or square-edged nucleus and abundant clear, glycogen-rich cytoplasm. As in this case, the tumor often contains fibrous septa, seen here as eosinophilic strands, which are infiltrated by chronic inflammatory cells including lymphocytes, macrophages, and occasional plasma cells. (Used with permission from Dr. Kelley Carrick.)

The standard treatment of dysgerminoma usually involves fertility-sparing surgery with unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (USO). In some extenuating circumstances, ovarian cystectomy may be considered (Vicus, 2010). Surgical staging is generally extrapolated from epithelial ovarian cancer, but lymphadenectomy is particularly important (Chap. 35). Of the malignant germ cell tumors, dysgerminoma has the highest rate of nodal metastases, approximately 25 to 30 percent (Kumar, 2008). Although staging deviations do not adversely affect survival, comprehensive staging allows a safe observation strategy for stage IA tumors (Billmire, 2004; Palenzuela, 2008).

Preservation of the contralateral ovary leads to “recurrent” dysgerminoma in 5 to 10 percent of retained gonads during the next 2 years. This finding in many cases is thought to reflect the high rate of clinically occult disease in the remaining ovary rather than true recurrence. Indeed, at least 75 percent of recurrences develop within the first year of diagnosis (Vicus, 2010). Other common recurrence sites are within the peritoneal cavity or retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Despite this significant incidence of recurrent disease, a conservative surgical approach does not adversely affect long-term survival because of this cancer’s sensitivity to chemotherapy (Liu, 2013).

Dysgerminomas have the best prognosis of all malignant ovarian germ cell tumor variants. Two thirds are stage I at diagnosis, and the 5-year disease-specific survival rate approximates 99 percent (Table 36-3). Even those with advanced disease have high survival rates following chemotherapy. For example, those with stage II-IV disease have a greater than 98-percent survival rate with platinum-based agents (Chan, 2008).

These tumors account for 10 to 20 percent of all malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. These lesions were previously called endodermal sinus tumors, but the terminology has been revised. One third of individuals are premenarchal at the time of initial presentation. Involvement of both gonads is rare, and the other ovary is usually involved with metastatic disease only when there are other metastases in the peritoneal cavity.

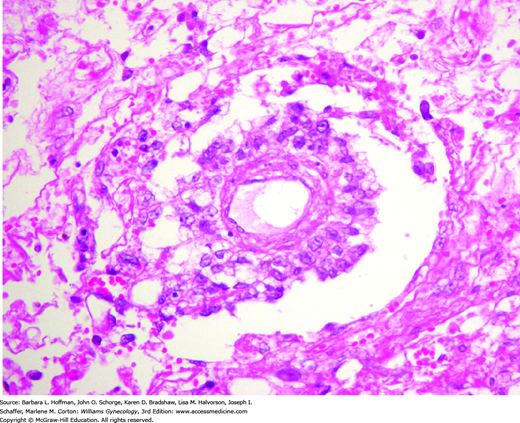

Grossly, these tumors form solid masses that are more yellow and friable than dysgerminomas. They are often focally necrotic and hemorrhagic, with cystic degeneration and rupture. The microscopic appearance of yolk sac tumors is often diverse. The most common appearance, the reticular pattern, reflects extraembryonic differentiation, with the formation of a network of irregular anastomosing spaces that are lined by primitive epithelial cells. Schiller-Duval bodies are pathognomonic when present (Fig. 36-5). These characteristically have a single papilla, which is lined by tumor cells and contains a central vessel. Alpha-fetoprotein is commonly produced. As a result, yolk sac tumors usually contain cells that stain immunohistochemically for AFP, and serum levels can serve as a reliable tumor marker in posttreatment surveillance.

FIGURE 36-5

Schiller-Duval body. This structure consists of a central capillary surrounded by tumor cells, present within a cystic space that may be lined by flat to cuboidal tumor cells. When present, the Schiller-Duval body is pathognomonic for yolk sac tumor, although they are conspicuous in only a minority of cases. In any given case, Schiller-Duval bodies may be few in number, absent, or have atypical morphologic features. (Used with permission from Dr. Kelley Carrick.)

Yolk sac tumors are the deadliest malignant ovarian germ cell tumor type. As a result, all patients are treated with chemotherapy regardless of stage. Fortunately, more than half present with stage I disease, corresponding to a 5-year disease-specific survival rate of approximately 93 percent (Chan, 2008). Disadvantageously, yolk sac tumors have a greater propensity for rapid growth, peritoneal spread, and distant hematogenous dissemination to the lungs. Accordingly, individuals with stage II-IV disease have a 5-year survival rate ranging from 64 to 91 percent. Of tumor recurrences, most will occur within the first year, and treatment is usually ineffective (Cicin, 2009).

The rarest subtypes of nondysgerminomatous tumors are typically mixed with other more common variants and usually are not found in pure form.

Patients diagnosed with embryonal carcinoma are characteristically younger, with a mean age of 14 years, than those having other types of germ cell tumors. Epithelial cells resembling those of the embryonic disc form these primitive tumors. The solid disorganized sheets of large anaplastic cells, glandlike spaces, and papillary structures are distinctive and allow easy identification of these rare tumors (Ulbright, 2005). Although dysgerminomas are the most common germ cell tumor resulting from malignant transformation of gonadoblastomas in individuals with dysgenetic gonads, occasionally embryonal “testicular” tumors may also originate (LaPolla, 1990). Embryonal carcinomas typically produce hCG, and 75 percent also secrete AFP.

These rare tumors characteristically contain many embryolike bodies. Each has a small central “germ disc” positioned between two cavities, one mimicking an amnionic cavity and the other a yolk sac. Syncytiotrophoblast giant cells are frequent, but elements other than the embryoid bodies should constitute less than 10 percent of the tumor for the “polyembryoma” designation to be used. Conceptually, these tumors may be viewed as a bridge between the primitive (dysgerminoma) and differentiated (teratoma) germ cell tumor types. For this reason, polyembryomas are often considered to be the most immature of all teratomas (Ulbright, 2005). Serum AFP or hCG levels or both may be elevated in these individuals due to the yolk sac and syncytial components, respectively (Takemori, 1998).

Primary ovarian choriocarcinoma arising from a germ cell appears similar to gestational choriocarcinoma with ovarian metastases, which is discussed in Chapter 37. The distinction is important because nongestational tumors have a poorer prognosis (Corakci, 2005). The detection of other germ cell components indicates nongestational choriocarcinoma, whereas a concomitant or proximate pregnancy suggests a gestational form (Ulbright, 2005). Clinical manifestations are common and result from high hCG levels produced by these rare tumors. These elevated levels may induce sexual precocity in prepubertal girls or heavy, irregular bleeding in reproductive-aged women (Oliva, 1993).

Ovarian germ cell tumors have a mixed pattern of cellular differentiation in 25 to 30 percent of cases, although the incidence of these tumors has also declined by approximately 30 percent over the past few decades (Smith, 2006). Dysgerminoma is the most common component and is typically seen with yolk sac tumor or immature teratoma or both. The frequency of bilateral ovarian involvement depends on the presence or absence of a dysgerminoma component and increases when it is present. However, treatment and prognosis are determined by the nondysgerminomatous component (Low, 2000). For this reason, elevated serum hCG and particularly AFP levels in a woman with a presumed pure dysgerminoma should prompt a search for other germ cell components by a more extensive histologic evaluation (Aoki, 2003).

Due to a 60-percent increased incidence during the past few decades, immature teratomas are now the most common variant and account for 40 to 50 percent of all malignant ovarian germ cell tumors (Chan, 2008; Smith, 2006). They are composed of tissues derived from the three germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. The presence of immature or embryonal structures, however, distinguishes these tumors from the much more common and benign mature cystic teratoma (dermoid cyst). Bilateral ovarian involvement is rare, but 10 percent have a mature teratoma in the contralateral ovary. Tumor markers are often not elevated unless the immature teratoma is mingled with other germ cell tumor types. Alpha-fetoprotein, cancer antigen 125 (CA125), CA19-9, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) may be helpful in some cases (Li, 2002).

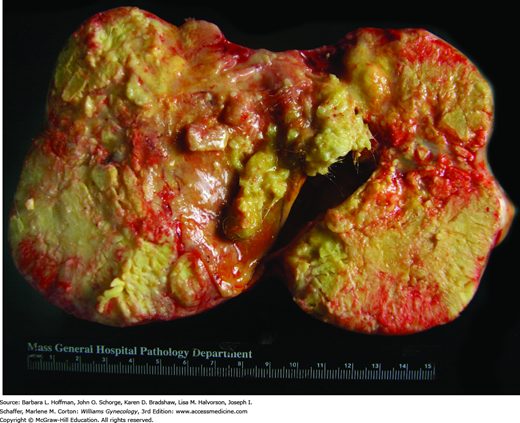

With gross external inspection, these tumors are large, rounded or lobulated, soft or firm masses. They frequently perforate the ovarian capsule and invade locally. The most frequent site of dissemination is the peritoneum and much less commonly the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. With local invasion, surrounding adhesions commonly form and are thought to explain the lower rates of torsion with this tumor compared with that of its benign mature counterpart (Cass, 2001). On cut surface, the interior is typically solid with intermittent cystic areas, but occasionally the reverse is seen, with solid nodules present only in the cyst wall (Fig. 36-6). Solid parts may correspond to the immature elements, cartilage, bone, or a combination of these. Cystic areas are filled with hair and with serous fluid, mucinous fluid, or sebum.

FIGURE 36-6

Immature teratoma. A. This opened surgical specimen shows characteristic solid and cystic architecture. As in mature teratomas, hair and other skin elements are often found. B. Immature teratomas contain a disorderly mixture of mature and immature tissues derived from the three germ cell layers—ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. Of the immature elements, immature neuroepithelium is the most common. Here, immature neuroepithelial cells arranged in rosettes lie within a background of mature neural tissue. (Used with permission from Dr. Kelley Carrick.)

Microscopic examination reveals a disorderly mixture of tissues. Of the immature elements, neuroectodermal tissues almost always predominate and are arranged as primitive tubules and sheets of small, round, malignant cells that may be associated with glia formation. The diagnosis is usually difficult to confirm during frozen section analysis, and most tumors are confirmed only on final pathologic review (Pavlakis, 2009). Tumors are graded 1 to 3 primarily by the amount of immature neural tissue they contain. O’Connor and Norris (1994) analyzed 244 immature teratomas and noted significant inconsistencies in grade assignment by different observers. For this reason, they proposed changing the system to two grades: low (previous grades 1 and 2) and high (previous grade 3). This practice, however, has not been universally accepted.

In general, survival is predicted most accurately by stage and by histologic grade of the tumor. For example, almost three quarters of immature teratomas are stage I at diagnosis and have a 5-year survival rate of 98 percent (Chan, 2008). Those with stage IA grade 1 immature teratomas have an excellent prognosis and do not require adjuvant chemotherapy (Bonazzi, 1994; Marina, 1999). Patients with stage II-IV disease have a 5-year survival rate ranging from 73 to 88 percent (Chan, 2008).

Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the standard care for these and other malignant germ cell tumors in reproductive-aged women. Beiner and colleagues (2004), however, treated eight women with early-stage immature teratoma with ovarian cystectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy and noted no recurrences.

Immature teratomas may be associated with mature tissue implants studding the peritoneum that do not increase the stage of the tumor or diminish the prospect of survival. However, these implants of mature teratomatous elements, even though benign, are resistant to chemotherapy and can enlarge during or after chemotherapy. Termed the growing teratoma syndrome, these implants require second-look surgery and resection to exclude recurrent malignancy (Zagame, 2006).

These rare tumors are the only germ cell variants that typically develop in postmenopausal women. Malignant areas are usually found as small nodules in the cyst wall or a polypoid mass within the lumen after removal of the entire mature cystic teratoma (Pins, 1996). Squamous cell carcinoma is most common and is found in approximately 1 percent of mature cystic teratomas (Fig. 36-7). Platinum-based chemotherapy with or without pelvic radiation is most often used for adjuvant treatment of early-stage disease (Dos Santos, 2007). However, regardless of treatment received, patients with advanced disease do poorly (Gainford, 2010).

Other uncommon types of malignant features may include basal-cell carcinomas, sebaceous tumors, malignant melanomas, adenocarcinomas, sarcomas, and neuroectodermal tumors. Moreover, endocrine-type neoplasms such as struma ovarii (teratoma composed mainly of thyroid tissue) and carcinoid may also be found within mature cystic teratomas.

A vertical abdominal incision is traditionally recommended if ovarian malignancy is suspected. However, increasingly, investigators with advanced endoscopic skills have noted laparoscopy to be a safe and effective alternative for women with smaller ovarian masses and apparent stage I disease (Shim, 2013).

If present, ascites is evacuated and sent for cytologic evaluation. Otherwise, washings of the pelvis and paracolic gutters are collected for analysis prior to manipulation of the intraperitoneal contents. The entire peritoneal cavity is systematically inspected. The ovaries are assessed for size, tumor involvement, capsular rupture, external excrescences, and adherence to surrounding structures.

Fertility-sparing USO is performed in all reproductive-aged women diagnosed with malignant ovarian germ cell tumors, as this conservative approach in general does not adversely affect survival (Chan, 2008; Lee, 2009). Following USO, blind biopsy or wedge resection of a normal-appearing contralateral ovary is not recommended. For those who have completed childbearing, hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) is appropriate (Brown, 2014b). In either case, following removal of the affected ovary, surgical staging by laparotomy or laparoscopy proceeds as previously described for epithelial ovarian cancer (Chap. 35) (Gershenson, 2007a). Because of tumor dissemination patterns, lymphadenectomy is most important for dysgerminomas, whereas staging peritoneal and omental biopsies are particularly valuable for yolk sac tumors and immature teratomas (Kleppe, 2014).

Cytoreductive surgery is recommended for advanced-stage malignant ovarian germ cell tumors if it can be accomplished with minimal residual disease (Bafna, 2001; Nawa, 2001; Suita, 2002). The same general principles for debulking are applied as described for epithelial ovarian cancer. Because of the exquisite chemosensitivity of most malignant germ cell tumors, however, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a reasonable option for patients thought to be unresectable (Talukdar, 2014).

Many women will be referred to an oncologist after USO for a tumor that was clinically confined to the excised ovary. For such patients, if initial surgical staging was incomplete, options may include a second surgery to complete primary staging, regular surveillance, or adjuvant chemotherapy. Unfortunately, few data support a preferred approach. Because of its minimally invasive qualities, laparoscopy is a particularly attractive option for delayed surgical staging following primary excision and has been shown to accurately detect those women who require chemotherapy (Leblanc, 2004). Surgical staging following primary excision, however, is less important for scenarios in which chemotherapy will be administered regardless of surgical findings such as clinical stage I yolk sac tumors and high-grade clinical stage I immature teratomas (Stier, 1996). In such patients, reassurance of no abnormalities by CT imaging is often sufficient prior to proceeding with adjuvant chemotherapy (Gershenson, 2007a).

Patients with malignant ovarian germ cell tumors are followed by careful clinical, radiologic, and serologic surveillance every 3 months for the first 2 years after therapy completion (Dark, 1997). Ninety percent of recurrences develop within this time frame (Messing, 1992). Second-look surgery at the completion of therapy is not necessary in women with completely resected disease or in those individuals with advanced tumor that does not contain teratoma. However, incompletely resected immature teratoma is the one circumstance among all types of ovarian cancer in which patients clearly benefit from second-look surgery and excision of chemorefractory tumor (Culine, 1996; Rezk, 2005; Williams, 1994).

Stage IA dysgerminomas and stage IA grade 1 immature teratomas do not require additional chemotherapy. More advanced disease and all other histologic types of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors have historically been treated with combination chemotherapy after surgery (Suita, 2002; Tewari, 2000). However, there is a strong trend toward exploring the feasibility of surgery followed by close surveillance in pediatric and adolescent girls (Billmire, 2014). Because chemotherapy remains effective when used at the time of relapse, some investigators are attempting to identify additional low-risk, early-stage subgroups that may be observed postoperatively and thereby avoid treatment-related toxicity (Bonazzi, 1994; Cushing, 1999; Dark, 1997). However, before this strategy can be incorporated into general practice, additional large studies are needed.

The standard regimen is a 5-day course of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) given every 3 weeks (Gershenson, 1990; Williams, 1987). Modified 3-day BEP combinations are also safe and effective (Chen, 2014; Dimopoulos, 2004). Carboplatin and etoposide, given in three cycles, has shown promise as an alternative for selected patients (Williams, 2004). For women with incompletely resected disease, at least four courses of BEP are usually recommended (Williams, 1991).

Chemotherapy has replaced radiation as the preferred adjuvant treatment for all types of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. This transition was prompted primarily by the exquisite sensitivity of these tumors to either modality, but higher likelihood of retained ovarian function using chemotherapy (Solheim, 2015

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree