INTRODUCTION

Malignant tumors of the uterine corpus are broadly divided into three main types: carcinomas, sarcomas, and carcinosarcomas. Although the latter two categories are rarely encountered, they tend to behave more aggressively and contribute to a disproportionately higher number of uterine cancer deaths. Pure sarcomas differentiate toward smooth muscle (leiomyosarcoma) or toward endometrial stroma (endometrial stromal tumors). Carcinosarcomas are mixed tumors demonstrating both epithelial and stromal components. These have also been known as malignant mixed müllerian tumor (MMMT). In general, uterine sarcomas and carcinosarcomas grow quickly, lymphatic or hematogenous spread occurs early, and the overall prognosis is poor. However, there are several notable exceptions among these tumors.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

Sarcomas account for approximately 3 to 8 percent of all malignancies of the uterine corpus (Brooks, 2004; D’Angelo, 2010; Major, 1993). Historically, uterine sarcomas included carcinosarcomas, accounting for 40 percent of cases; leiomyosarcomas, 40 percent; endometrial stromal sarcomas, 10 to 15 percent; and undifferentiated sarcomas, 5 to 10 percent. In 2009, the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) reclassified carcinosarcomas as a metaplastic form of endometrial carcinoma. Despite this, carcinosarcomas are still commonly included in most retrospective studies of uterine sarcomas and in the 2014 World Health Organization (WHO) classification (Greer, 2015; Kurman, 2014; McCluggage, 2002).

Because of their infrequency, uterine sarcomas and carcinosarcomas have few identified risk factors. These include chronic excess estrogen exposure, tamoxifen use, African American race, and prior pelvic radiation. In contrast, combination oral contraceptive pill use and smoking appear to lower risks for some of these tumors (Felix, 2013).

PATHOGENESIS

Leiomyosarcomas have a monoclonal origin, and although commonly believed to arise from benign leiomyomas, for the most part they do not. Instead, they appear to develop de novo as solitary lesions (Zhang, 2006). Supporting this theory, leiomyosarcomas have molecular pathways distinct from those of leiomyomas or normal myometrium (Quade, 2004; Skubitz, 2003). They are, however, often found in proximity to leiomyomas.

Endometrial stromal tumors (ESS) have heterogeneous chromosomal aberrations (Halbwedl, 2005). However, the pattern of rearrangements is clearly nonrandom, and chromosomal arms 6p and 7p are frequently involved (Micci, 2006). Translocations involving several chromosomes and the resultant fusion proteins are thought to be involved in ESS pathogenesis (Lee, 2012; Panagopoulos, 2012).

Uterine carcinosarcomas are monoclonal, biphasic neoplasms. Namely, they are composed of separate but admixed malignant epithelial and malignant stromal elements (D’Angelo, 2010; Wada, 1997). Both the carcinoma and sarcoma components are thought to arise from a common epithelial progenitor cell. Acquisition of any number of genetic mutations, including defects in p53 and DNA mismatch repair genes, may be sufficient to trigger tumorigenesis (Liu, 1994). These early molecular defects will be shared by both components as the tumor undergoes divergent carcinomatous and sarcomatous differentiation. Thereafter, acquired molecular defects will be discordant between the two components (Taylor, 2006). This genetic progression and subsequent diversion parallels the varying phenotypes observed in these tumors (Fujii, 2000).

DIAGNOSIS

As in endometrial cancer, abnormal vaginal bleeding is the most frequent symptom for uterine sarcomas and carcinosarcomas (Gonzalez-Bosquet, 1997). Pelvic or abdominal pain is also common. Up to one third of women will describe significant discomfort that may result from passage of clots, rapid uterine enlargement, or prolapse of a sarcomatous polyp through an effaced cervix (De Fusco, 1989). In addition, a profuse, foul-smelling discharge may be obvious, and gastrointestinal and genitourinary complaints are also frequent. Importantly, degenerating leiomyomas with necrosis can mimic these same signs and symptoms.

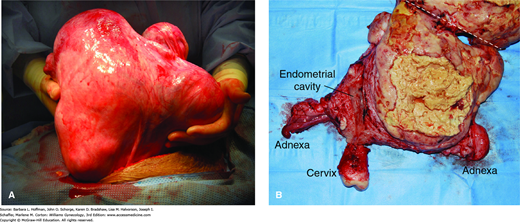

With rapid growth, a uterus may extend out of the pelvis into the mid- or upper abdomen (Fig. 34-1). Fortunately, the incidence of malignancy in such cases is low (<0.5 percent), and in most instances, benign enlarging leiomyomas are found (Leibsohn, 1990; Parker, 1994). Although uterine leiomyosarcomas do tend to grow quickly, no criteria define what constitutes significant growth. Despite these often-dramatic presentations, many women with uterine sarcoma and carcinosarcoma will have few symptoms other than abnormal vaginal bleeding and a seemingly normal uterus on physical examination.

FIGURE 34-1

Leiomyosarcoma. A. Intraoperative photograph of an enlarged uterus before hysterectomy. B. Surgical specimen has been bisected and remains joined at the fundus. The other half of the specimen lies above the white dashed line and out of view. The large tumor lies to the right of the endometrial cavity. It has central necrosis seen as yellow amorphous debris with the tumor borders. (Used with permission from Dr. Martha Rac.)

The sensitivity of an office endometrial biopsy or dilatation and curettage (D & C) to detect sarcomatous elements is lower than that for endometrial carcinomas. Specifically, with leiomyosarcoma, symptomatic women receive a correct preoperative diagnosis in only 25 to 50 percent of cases. This inability to accurately sample the tumor is probably related to the origin of these neoplasms in the myometrium rather than the endometrium. Similarly, endometrial stromal nodules and endometrial stromal sarcomas may be undetectable by Pipelle biopsy, especially if the neoplasm is intramural (Yang, 2002). With carcinosarcoma, sampling will more often lead to a correct diagnosis, although in many cases only the carcinomatous features are evident. The reverse is also true, and occasionally a uterine carcinosarcoma is suspected based on endometrial biopsy findings, but no sarcomatous features are found within the hysterectomy specimen.

Elevated preoperative serum cancer antigen 125 (CA125) levels may indicate extrauterine disease and deep myometrial invasion in patients with carcinosarcoma. After surgery, CA125 measurement may be a somewhat useful marker to monitor disease response (Huang, 2007).

Imaging studies are often helpful if sarcoma is diagnosed before hysterectomy. In most cases, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis is routinely performed. This serves at least two purposes. First, sarcomas often violate normal soft tissue planes in the pelvis, and therefore, unresectable tumors may be identified preoperatively. Second, extrauterine metastases may be found. In either case, treatment may be altered based on radiographic findings.

If a diagnosis is still in question, magnetic resonance (MR) imaging helps distinguish uterine sarcoma from a benign “mimic” (Kido, 2003). As a diagnostic tool for sarcoma, sonography is far less helpful. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning is most effective in the setting of recurrent uterine sarcoma but offers little advantage compared with CT or MR imaging (Sharma, 2012).

Preoperative consultation with a gynecologic oncologist is recommended for any patient with a biopsy suggesting uterine sarcoma or carcinosarcoma. The potential for intraabdominal metastases and disruption of tissue planes within the pelvis increases the technical difficulty and surgical risks. The approach to staging is subtly dissimilar to that of endometrial carcinomas. For example, due to the low rate of metastasis, only sampling nodes suspicious for leiomyosarcomas may be appropriate instead of performing complete pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy (Leitao, 2003; Major, 1993). Moreover, ovarian preservation may be suitable with certain sarcomas because of their low risk for spread to the adnexa (Kapp, 2008; Li, 2005). In general, a treatment plan is best organized preoperatively, if possible.

Many uterine sarcomas and carcinosarcomas are not diagnosed until surgery or several days later when a pathology report is available. As a result, unstaged cases are common, and a gynecologic oncologist is consulted at the earliest feasible time. If the diagnosis is made postoperatively, the criteria to recommend surveillance only, reoperation, or radiotherapy vary widely and depend on the sarcoma type and other clinical circumstances. Generally, these options are less straightforward than in typical endometrial carcinomas, largely due to the rarity of these tumors and the comparatively limited data supporting one strategy over another.

With adoption of minimally invasive surgery (MIS), gynecologists are faced with uterine or myoma extraction through small incisions. Tissue fragmentation using power morcellation is one approach, but morcellation and dispersion of uterine or cervical cancers are concerns. In general, encountering unexpected sarcoma during surgery for presumed benign disease is rare, and rates range from 0.09 to 0.6 percent (Lieng, 2015; Lin, 2015). These investigators also found no clear preoperative risk factors. However, if a patient undergoes inadvertent morcellation and dispersion of an occult sarcoma, it may worsen her prognosis (Perri, 2009). In 2014, the Food and Drug Administration warned that power morcellator use should be curtailed in patients who are peri- or postmenopausal or who are candidates for en bloc removal through the vagina or a minilaparotomy. Moreover, if uncontained intraperitoneal morcellation is selected, patients should be aware of the risks that it poses.

PATHOLOGY

Uterine mesenchymal tumors are classified broadly into pure and mixed tumors (Table 34-1). Also, the term homologous denotes tissues normally found in the uterus and heterologous refers to tissue foreign to the uterus. Pure sarcomas are virtually all homologous and differentiate into mesenchymal tissue that is normally present within the uterus, such as smooth muscle (leiomyosarcoma) or stromal tissue within the endometrium (endometrial stromal tumors). Pure heterologous sarcomas, such as chondrosarcoma, are rare.

| Mesenchymal tumors |

|

| Mixed epithelial and mesenchymal tumors |

|

Mixed sarcomas contain a malignant mesenchymal component admixed with an epithelial element. If the epithelial element is also malignant, the tumor is termed carcinosarcoma. If the epithelial element is benign, the term adenosarcoma is used. Carcinosarcomas can be either homologous or heterologous, reflecting the pluripotentiality of the uterine primordium.

Leiomyosarcomas account for 1 to 2 percent of all uterine malignances. In a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database study of 1396 patients, the median age at presentation was 52 years. Most tumors (68 percent) were stage I at the time of diagnosis, and stage II (3 percent), stage III (7 percent), and stage IV cancer (22 percent) formed the remainder (Kapp, 2008).

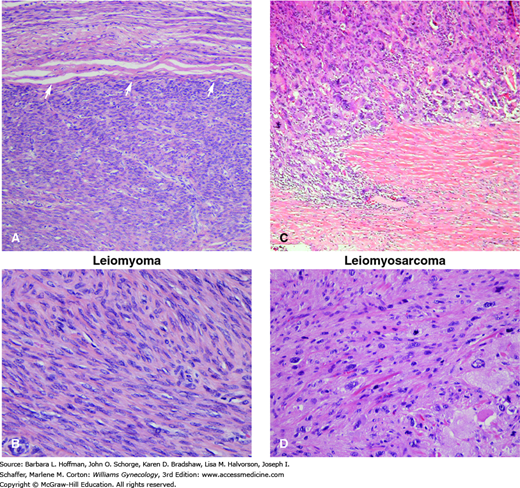

The histologic criteria for diagnosing leiomyosarcoma are somewhat controversial but include the frequency of mitotic figures, extent of nuclear atypia, and presence of coagulative tumor cell necrosis (Fig. 34-2). In reading Table 34-2, each row illustrates combinations of histologic findings that may be found in leiomyosarcomas. In most cases, the mitotic index exceeds 15 mitotic figures total when 10 high-power fields are examined, moderate to severe cytologic atypia is seen, and tumor cell necrosis is prominent (Hendrickson, 2003; Zaloudek, 2011). Occasionally, a leiomyosarcoma will be reported as low-, intermediate-, or high-grade, but the overall utility of grading is controversial, and no universally accepted grading system exists.

| Coagulative Tumor Cell Necrosis | Mitotic Index a | Degree of Atypia |

| Present Present Absent | ≥10 MF/10 HPF Any ≥10 MF/10 HPF | None Diffuse, significant Diffuse, significant |

FIGURE 34-2

Leiomyoma (A, B) and leiomyosarcoma (C, D). A. Leiomyomas tend to be well-circumscribed masses. This leiomyoma shows a well-demarcated interface (arrows) with the less cellular myometrium above it. B. Although leiomyomas may have variable histologic features, most are composed of bland spindled cells with blunt-ended nuclei and limited mitotic activity. C. Leiomyosarcoma is a malignant smooth muscle neoplasm that may differ markedly in its microscopic appearance from case to case. Generally, leiomyosarcoma shows some combination of coagulative tumor necrosis, increased mitotic activity, and/or nuclear atypia. This example has marked nuclear atypia and pleomorphism and an infiltrative growth pattern at its periphery. This differs from the usually smooth, pushing border of typical leiomyomas. D. This particular example has moderate to marked nuclear atypia. (Used with permission from Drs. Kelley Carrick and Raheela Ashfaq.)

Tumors that show some worrisome histologic features, such as necrosis or nuclear atypia, but that cannot be diagnosed reliably as benign or malignant based on generally applied criteria fall into this category. The diagnosis should be used sparingly and is reserved for smooth muscle neoplasms whose appearance is ambiguous (Hendrickson, 2003).

Significantly less common than leiomyosarcomas, the group of endometrial stromal tumors comprise fewer than 10 percent of all uterine sarcomas. In a SEER database study of 831 patients, the median age at diagnosis was 52 years (Chan, 2008). Although constituting a wide morphologic spectrum, endometrial stromal tumors are composed exclusively of cells that resemble the endometrial stroma, and this category includes both benign stromal nodules and malignant stromal tumors (see Table 34-1).

Historically, there has been controversy in subdividing these tumors. The division of endometrial stromal sarcomas into low-grade and high-grade categories has fallen out of favor. In its place, the designation endometrial stromal sarcoma is now best restricted to neoplasms that were formerly referred to as low-grade. Alternatively, the term high-grade undifferentiated sarcoma is believed to more accurately reflect those tumors without recognizable evidence of a definite endometrial stromal phenotype. These lesions are almost invariably high grade and often resemble the mesenchymal component of a uterine carcinosarcoma (Oliva, 2000). In this revised classification, the distinctions are not determined by mitotic count but by features such as nuclear pleomorphism and necrosis (Evans, 1982; Hendrickson, 2003).

Representing less than a quarter of tumors in the endometrial stromal tumor group, these rare nodules are benign, characterized by a well-delineated margin, and composed of neoplastic cells that resemble proliferative-phase endometrial stromal cells. Grossly, the tumor is a solitary, round or oval, fleshy nodule measuring a few centimeters. Histologically, they are distinguished from endometrial stromal sarcomas by their lack of myometrial infiltration (Dionigi, 2002). Because these nodules are benign, myomectomy is an appropriate option. However, because differentiation between endometrial stromal sarcoma and this benign lesion cannot be determined clinically, it is important to remove the entire nodule. Thus, for large lesions, hysterectomy may be required (Hendrickson, 2003).

The precise frequency of these tumors is difficult to estimate because they are excluded from some reports and included in others, and the terminology used has been inconsistent. In general, endometrial stromal sarcomas (formerly called low grade) are thought to be the most frequently encountered stromal tumor variant and are twice as common as high-grade undifferentiated sarcomas.

Typically, they extensively invade the myometrium and extend to the serosa in approximately half of cases (Fig. 34-3). Less often, they present as a solitary well-delineated, predominantly intramural mass that is difficult to grossly distinguish from an endometrial stromal nodule. Microscopically, endometrial stromal sarcomas resemble the stromal cells of proliferative-phase endometrium (Fig. 34-4).

FIGURE 34-4

Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS), same patient as in Figure 34-3. A.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree