INTRODUCTION

Vulvar cancers comprise only about 4 percent of all gynecologic malignancies. Most vulvar cancers are diagnosed at an early stage (I and II). Advanced disease is found mainly in older women, perhaps due to clinical and behavioral barriers that lead to diagnostic delays. Thus, biopsy of any abnormal vulvar lesion is imperative to help diagnose this cancer early.

In the United States, vulvar cancers carry a comparatively good prognosis with a 5-year relative survival rate of 78 percent (Stroup, 2008). For resectable disease, traditional therapy includes radical excision of the vulva plus inguinal lymphadenectomy or plus sentinel lymph node biopsy. For advanced stages, chemoradiation may be used either primarily or as an adjunct to surgery to aid tumor control. All of these treatments can result in extensive short- and long-term morbidity and dramatic anatomic and functional deformity. Accordingly, vulvar cancer management recently has trended toward more conservative surgery that preserves oncologic outcome, lessens morbidity, and improves psychosexual well-being.

RELEVANT ANATOMY

The vulva includes the mons pubis, labia majora and minora, clitoris, vestibule, vestibular bulbs, Bartholin glands, lesser vestibular glands, paraurethral glands, and the urethral and vaginal openings. Lateral margins of the vulva are the labiocrural folds (Fig. 38-25). Vulvar cancer may involve any of these external structures and typically arises within the covering squamous epithelium. Unlike the cervix, the vulva lacks an identifiable transformation zone. That said, squamous neoplasia arises predominantly on the vestibule at the border between the vulvar keratinized stratified squamous epithelium, which lies laterally, and the nonkeratinized squamous mucosa, which lies medially. This demarcation line is termed Hart line.

Deep to the vulva are the superficial and deep urogenital triangle compartments. The superficial space lies between Colles fascia (superficial perineal fascia) and the perineal membrane (deep perineal fascia) (Fig. 38-26). Within this space lie the ischiocavernosus, bulbospongiosus, and transverse perineal muscles and the highly vascular vestibular bulb and clitoral crus. During radical vulvectomy, dissection is carried to the depth of the perineal membrane. As a result, contents of this superficial urogenital triangle compartment that lie beneath the mass are removed during tumor excision.

The lymphatics of the vulva and distal third of the vagina typically drain into the superficial inguinal node group (Fig. 38-29). From here, lymph travels through the deep femoral lymphatics and the node of Cloquet to the pelvic nodal groups. Importantly, lymph can also drain directly from the clitoris and upper labia to the deep femoral nodes (Way, 1948). Vulvar lymphatics cross at the mons pubis and the posterior fourchette but do not cross the labiocrural folds (Morley, 1976). Thus, lesions found within 2 cm of the midline may spread to lymph nodes on either side. In contrast, lateral lesions rarely send metastases to contralateral nodes. This anatomy point influences the decision for ipsilateral or bilateral node dissection, as discussed later.

The superficial inguinal nodes cluster within the femoral triangle formed by: the inguinal ligament, sartorius muscle, and adductor longus muscle. The deep femoral nodes lie within the borders of the fossa ovalis and just medial to the femoral vein. An inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy typically refers to removal of both superficial inguinal and deep femoral lymph nodes (Levenback, 1996).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In the United States, women have a 1 in 333 chance of developing this cancer at some point. In 2014, approximately 4850 new vulvar cancers and 1030 cancer deaths were predicted (National Cancer Institute, 2014). The age-adjusted incidence of invasive vulvar tumors in the United States has trended upward during the past three decades due to an aging population and greater longevity of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected women. This increase persists among all age groups and all geographic areas (Bodelon, 2009). Specifically, the age-adjusted incidence of vulvar carcinoma in situ (CIS) has increased by 3.5 percent per year, whereas that of invasive cancers has risen by 1 percent yearly (Jemal, 2010).

Of vulvar tumors, approximately 90 percent are squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 31-1). Malignant melanoma is the second most common, but rare histologic subtypes may also be encountered (Table 31-1).

| Vulvar carcinomas |

|

| Vulvar malignant melanoma |

| Vulvar sarcoma |

|

| Metastatic cancers to vulva |

| Yolk sac tumors |

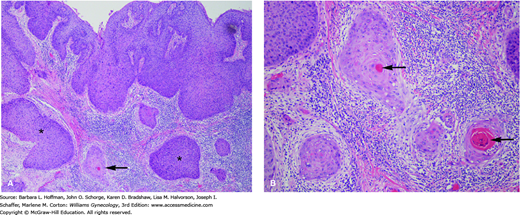

FIGURE 31-1

Vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. A. Low-power view. The surface epithelium shows high-grade squamous dysplasia. Nests of invasive squamous cell carcinoma (arrow) are present. A brisk chronic inflammatory infiltrate is present as is often the case with invasive squamous cell carcinoma. Portions of the surface epithelium extend deep and are cut tangentially (asterisks), giving the false impression of invasive tumor at these sites. B. Tumor shows classic diagnostic features of invasive squamous cell carcinoma that include a squamoid appearance, intercellular bridges, and brightly eosinophilic keratin pearls (arrows). Nests of invasive tumor are surrounded by chronic inflammation. (Used with permission from Dr. Kelley Carrick.)

RISK FACTORS

Age is a prominent factor and positively correlates with this cancer. Less than 20 percent of affected women are younger than 50 years, and more than half of cases develop in women older than 70. Survival rates also differ by age. Kumar and associates (2009) described a hazard ratio of nearly 4 for death in women older than 50 years compared with younger women. Last, vulvar cancer pathology can be divided into two distinct age-dependent profiles. Those that develop in younger women (<55 years) tend to have the same risk profile as other anogenital cancers. These cancers are usually described histologically as basaloid or warty and are linked with human papillomavirus (HPV) in 50 percent of cases. In contrast, older affected women typically are nonsmokers and lack a history of prior sexually transmitted infections. Their cancers are largely keratinizing, and HPV DNA is found in only 15 percent (Canavan, 2002; Madeleine, 1997). Such HPV-independent vulvar cancers have been associated with lichen sclerosus and with genetic alterations such as mutations in p53. This tumor suppressor gene normally modulates cell death, and its mutation can be carcinogenic.

Infection with high-risk HPV serotypes is another vulvar cancer risk. Serotype 16 predominates, although HPV serotypes 18, 31, 33, and 45 are also reported. Although HPV is implicated in many vulvar cancers, stronger correlations are noted between HPV infection and preinvasive vulvar lesions (Hildesheim, 1997). Specifically, HPV DNA is detected in 50 to 70 percent of invasive lesions but is seen in >90 percent of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) lesions (Gargano, 2012). HPV becomes a stronger contributor when combined with other cofactors such as smoking or herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection (Madeleine, 1997). Women who have smoked and have a history of HPV genital warts have a 35–fold increased risk for developing vulvar cancer compared with women without these predispositions (Brinton, 1990; Kirschner, 1995). For these reasons, prophylactic vaccination against high-risk HPV may ultimately reduce vulvar cancer incidence. A full discussion of HPV and VIN is found in Chapter 29

Herpes simplex virus infection is also linked with vulvar cancer in several studies (Hildesheim, 1997; Madeleine, 1997). As noted, the association is more prominent when coupled with other cofactors such as smoking. Thus, the causal link between HSV alone and vulvar cancer is not considered conclusive.

Chronic immunosuppression can predispose to vulvar cancer. For example, transplant patients have a high incidence. In this group, vulvar cancer develops at a much younger age than in the general population, and more than 50 percent have a prior history of condyloma acuminata (Penn, 2002). With HIV, vulvar cancer rates are also increased (Elit, 2005; Frisch, 2000). And, of the increased high-grade VIN and invasive vulvar carcinoma incidence noted in younger women, HIV-infected patients make up the majority (Casolati, 2003). A possible explanation for this is the association of HIV and high-risk HPV subtypes. However, vulvar cancer is not yet considered an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining malignancy. Because of these links with vulvar cancer, we recommend that all immunocompromised women undergo thorough vulvar inspection and, when indicated, vulvoscopy and biopsy.

Lichen sclerosus is a chronic vulvar inflammatory disease and is related to vulvar cancer development. Keratinocytes affected by lichen sclerosus show a proliferative phenotype and can exhibit markers of neoplastic progression. As such, lichen sclerosus may be a precursor lesion in some invasive squamous vulvar cancers (Rolfe, 2001). Vulvar cancers coexistent with lichen sclerosus tend to develop in older women, predominate in near the clitoris, and lack association with VIN 3.

Last, progression from VIN 3 to invasive cancer is suspected. Several reports demonstrate that in a small percentage of women older than 30 years, untreated lesions can progress to invasive cancer within a mean of 4 years (Jones, 2005; van Seters, 2005). Although this progression cannot be conclusively validated, we recommend that patients with moderate and severe vulvar dysplasias receive early definitive treatment (Chap. 29).

DIAGNOSIS

Women with VIN and vulvar cancer commonly present with pruritus and a visible lesion (Fig. 31-2). However, pain, bleeding, ulceration, or inguinal mass may be other complaints (Fig. 31-3). Manifestations can persist for weeks or months before diagnosis, as many patients may be embarrassed or may not recognize the significance of their symptoms.

Lesions may be raised, ulcerated, pigmented, or warty, but in younger women with multifocal disease, a well-defined mass is not always present. Importantly, other clinical entities may present similarly and include preinvasive neoplasia (VIN), infection, chronic inflammatory disease, and granulomatous disease. Thus, the goal of evaluation is to obtain an accurate and definitive pathologic diagnosis.

For this, colposcopic examination of the vulva, termed vulvoscopy, can direct biopsy site selection. To begin, the vulva is soaked with 3-percent acetic acid for 5 minutes to allow adequate penetration into the keratin layer. This aids identification of acetowhite areas and abnormal vascular patterns, which are characteristics of vulvar neoplasia. The entire vulva and perianal skin are systematically examined. We recommend obtaining multiple biopsies, as illustrated in Figure 4-2, from the most suspicious raised or dyspigmented skin. Specimens removed with a Keyes punch should be approximately 4 mm thick to include the surface epithelial lesion and the underlying stroma. This permits evaluation for invasion and depth of invasion. Concurrent colposcopic examination of the cervix and vagina and careful evaluation of the perianal area are recommended to diagnose any synchronous lesions or associated neoplasm of the lower genital tract.

Following histologic diagnosis, a patient with vulvar cancer is assessed for the clinical extent of disease and for comorbid conditions. Thus, detailed physical examination includes measurement of the primary tumor and evaluation of cancer extension into other genitourinary system compartments, the anal canal, the bony pelvis, and inguinal lymph nodes. At our institution, if a thorough physical examination is not possible because of patient discomfort or disease extent, an examination under anesthesia is performed. This may be coupled with cystourethroscopy, proctosigmoidoscopy, or both if suspicion of tumor invasion into the urethra, bladder, or anal canal is high (Fig. 31-4).

Women with small tumors and clinically negative groin nodes require few additional diagnostic studies other than those needed for surgical preparation (Chap. 39). Although not a formal part of surgical tumor staging, preoperative imaging may complement staging in those with larger tumors or with clinically suspected metastatic disease. In such cases, a chest radiograph and computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), or magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the abdomen and pelvis provide information regarding disease extent or metastases that may modify preoperative planning.

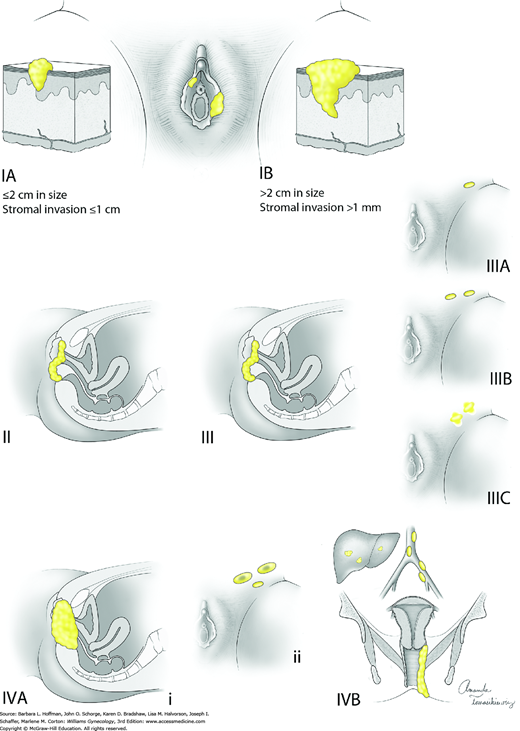

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) advocates surgical staging of patients with vulvar cancer that is based on a tumor, nodal, metastatic (TNM) classification. Thus, staging involves: (1) primary tumor resection to obtain tumor dimensions and (2) dissection of superficial and deep inguinofemoral lymph nodes to evaluate tumor spread (Pecorelli, 2009). This system is used to direct treatment and predict prognosis (Van der Steen, 2010). Table 31-2 and Figure 31-5 describe FIGO staging and American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging criteria for all vulvar cancer types except melanoma. This cancer’s staging is discussed separately on page 688. The general nuanced differences between FIGO and AJCC systems are described in Chapter 30.

| TNM a | Stage b | Characteristics |

| I | Tumor confined to the vulva | |

| T1a | IA | Lesions ≤2 cm in size, confined to the vulva or perineum and with stromal invasion ≤1.0 mm c, no nodal metastasis |

| T1b | IB | Lesions >2 cm in size or with stromal invasion >1.0 mm c, confined to the vulva or perineum, with negative nodes |

| T2 | II | Tumor of any size with extension to adjacent perineal structures (1/3 lower urethra, 1/3 lower vagina, anus) with negative nodes |

| III | Tumor of any size with or without extension to adjacent perineal structures (1/3 lower urethra, 1/3 lower vagina, anus) with positive inguinofemoral lymph nodes | |

| N1b N1a | IIIA | (i) With 1 lymph node metastasis (≥5 mm), or (ii) 1–2 lymph node metastasis(es) (<5 mm) |

| N2b N2a | IIIB | (i) With 2 or more lymph node metastases (≥5 mm), or (ii) 3 or more lymph node metastases (<5 mm) |

| N2c | IIIC | With positive nodes with extracapsular spread |

| IV | Tumor invades other regional (2/3 upper urethra, 2/3 upper vagina), or distant structures | |

| T3 | IVA | Tumor invades any of the following: (i) upper urethral and/or vaginal mucosa, bladder mucosa, rectal mucosa, or fixed to pelvic bone, or (ii) fixed or ulcerated inguinofemoral lymph nodes |

| M1 | IVB | Any distant metastasis including pelvic lymph nodes |

PROGNOSIS

Overall survival rates of women with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva are relatively good. Five-year survival rates of 75 to 90 percent are routinely cited for stage I and II disease. As anticipated, 5-year survival rates for higher stages are poorer, and rates of 54 percent for stage III and 16 percent for stage IVB are reported (American Cancer Society, 2015). Apart from FIGO stage, other important prognostic factors include lymph node metastasis, lesion size, depth of invasion, resected-margin status, and lymphatic vascular space involvement (LVSI) (Table 31-3).

Of these, lymph node metastasis is the single most important vulvar cancer predictor, since inguinal node metastasis reduces long-term survival rates by 50 percent (Farias-Eisner, 1994; Figge, 1985). Nodal status is determined by surgical resection and histologic evaluation. Among patients with nodal metastasis, other factors further predict poor prognosis. These include a high number of involved lymph nodes, large nodal metastasis size, extracapsular invasion, and fixed or ulcerated nodes (Homesley, 1991; Origoni, 1992).

Tumor diameter also influences survival rates. But this stems mainly from the positive correlation between lesion size and nodal metastasis rates (Homesley, 1993).

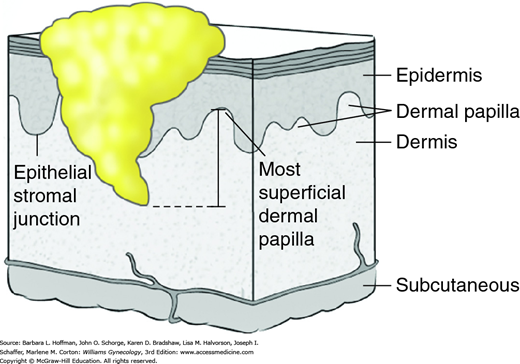

Depth of invasion is another prognostic element. As shown in Figure 31-6, this depth is measured from the basement membrane to the deepest point of invasion (Kurman, 2014). Tumors with a depth of invasion <1 mm carry little or no risk of inguinal lymph node metastasis. However, increased nodal metastasis rates positively correlate with greater invasion rates.

Surgical margins that are tumor-free decrease local tumor recurrence rates, and traditionally a 1- to 2-cm tumor-free margin is desired. More specifically, two large retrospective series demonstrated that a tumor-free surgical margin ≥8 mm yielded a high rate of local control. In contrast, if tumor was found within this 8-mm margin, the recurrence rate was 23 to 48 percent (Chan, 2007; Heaps, 1990). Hence, when lesions are close to the clitoris, anus, urethra, or vagina, a 1-cm surgical tumor-free margin may be used to preserve important anatomy yet still provide optimal resection.

Lymphatic vascular space invasion (LVSI) describes histologic identification of tumor cells within lymphatic vessels and is a predictor of early disease recurrence (Preti, 2005). LVSI is also associated with a higher frequency of lymph node metastasis and a lower overall 5-year survival rate (Hoskins, 2000).

TREATMENT

For vulvar cancer treatment, surgery is often an integral part. Potential procedures, in increasing order of radicality, include wide local excision (WLE), radical partial vulvectomy, and radical complete vulvectomy.

Of these, wide local excision is appropriate only for microinvasive tumors (stage IA) of the vulva. With this excision, also termed simple partial vulvectomy, 1-cm surgical margins are obtained around the lesion. Deep surgical margins measuring 1 cm are also preferred. This deep margin usually corresponds to Colles fascia (Fig. 38-25).

With radical partial vulvectomy (Section 46-25), tumor-containing portions of the vulva are completely removed, wherever they are located. Skin margins are 1 to 2 cm, and excision extends deep to the perineal membrane (Fig. 31-7). Radical partial vulvectomy is typically reserved for unifocal lesions that are clinically confined to the labia majora, labia minora, mons, vestibule, and/or perineum and that have limited involvement of the adjacent urethra, vagina, and/or anus. Moreover, only patients with a solitary tumor that is not too large or too extensive and with an otherwise normal vulva are considered for this vulva-conserving surgery.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree