INTRODUCTION

Pediatric gynecology is a unique subspecialty that encompasses knowledge from various specialties including general pediatrics, gynecology, reproductive endocrinology, as well as pediatric endocrinology and pediatric urology. Treatment of a particular patient may thus require the collaboration of clinicians from one or more of these fields.

Gynecologic disorders in children can differ greatly from those encountered in the adult female. Even the simple physical examination of the genitalia differs significantly. A thorough understanding of these differences can aid in diagnosing the various gynecologic abnormalities seen in this age group.

PHYSIOLOGY AND ANATOMY

A carefully orchestrated cascade of events unfolds in the neuroendocrine system and regulates development of the female reproductive system. In utero, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons develop in the olfactory placode. These neurons migrate through the forebrain to the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus by 11 weeks’ gestation (Fig. 16-5). They form axons that extend to the median eminence and to the capillary plexus of the pituitary portal system (Fig. 15-11). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone, a decapeptide, is influenced by higher cortical centers and is released from these neurons in a pulsatile fashion into the pituitary portal plexus. As a result, by midgestation, the GnRH “pulse generator” stimulates secretion of gonadotropins, that is, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), from the anterior pituitary. In turn, the pulsatile release of gonadotropins stimulates ovarian synthesis and release of gonadal steroid hormones. Concurrently, accelerated germ cell division and follicular development begins, resulting in the creation of 6 to 7 million oocytes by 5 months’ gestation. By late gestation, gonadal steroids exert a negative feedback on secretion of both hypothalamic GnRH and pituitary gonadotropins. During this time, oocyte number decreases through a process of gene-related apoptosis to reach a level of 1 to 2 million by birth (Vaskivuo, 2001).

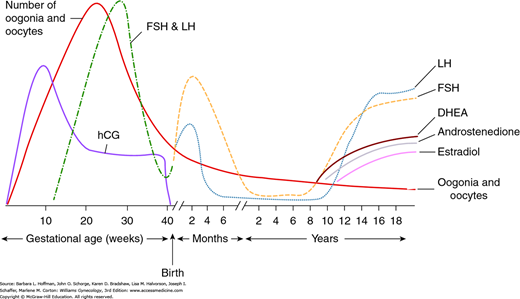

At birth, FSH and LH concentrations rise abruptly in response to the fall in placental estrogen levels and are highest in the first 3 months of life (Fig. 14-1). This transient rise in gonadotropin levels is followed by an increase in gonadal steroid concentrations, which is thought to explain instances of neonatal breast budding, minor bleeding from endometrial shedding, short-lived ovarian cysts, and transient white vaginal mucous discharge. Following these initial months, gonadotropin levels gradually decline to reach prepubertal levels by age 1 to 2 years.

FIGURE 14-1

Variation in oocyte number and hormone levels during prenatal and postnatal periods. (DHEA = dehydroepiandrosterone; FSH = follicle-stimulating hormone; hCG = human chorionic gonadotropin; LH = luteinizing hormone.) (Reproduced with permission from Fritz M, Speroff L: Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility, 8th ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.)

The childhood years are thus characterized by low plasma levels of FSH, LH, and estradiol. Estradiol levels typically measure <10 pg/mL, and LH values are <0.3 mIU/mL. Both may be assessed if precocious development is suspected (Neely, 1995; Resende, 2007). During childhood, ovaries undergo active follicular growth and oocyte atresia. As a result of this attrition, by puberty, only 300,000 to 500,000 oocytes remain (Fritz, 2011).

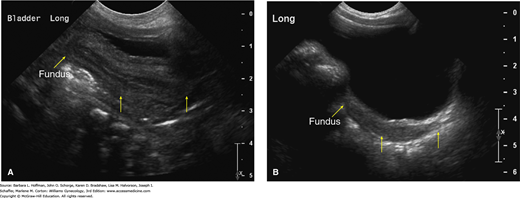

Pelvic anatomy also changes during early childhood. In the neonate, sonographically, the uterus measures approximately 3.5 cm in length and 1.5 cm in width. Because the cervix is larger than the fundus, the neonatal uterus is typically spade-shaped (Fig. 14-2) (Nussbaum, 1986). An echogenic central endometrial stripe is common and reflects the transiently elevated gonadal steroid levels described earlier. Fluid is seen within the endometrial cavity in 25 percent of female newborns. Ovarian volume measures ≤1 cm3, and small cysts are frequently found (Cohen, 1993; Garel, 2001).

FIGURE 14-2

Transabdominal pelvic sonograms. A. Normal neonatal uterus. Midline longitudinal sonogram of the pelvis in this 3-day-old newborn demonstrates the uterus posterior to the bladder. Yellow arrows mark the fundus, isthmus, and cervix, respectively. The anteroposterior (AP) diameter of the cervix is greater than that of the fundus and creates a spade-shaped uterus. Due to the effect of maternal and placental hormones, a central echogenic endometrial cavity stripe is clearly visible. B. Normal prepubertal uterus. Midline longitudinal sonogram of the pelvis in this 3-year-old girl demonstrates the uterus posterior to the bladder. Yellow arrows mark the fundus, isthmus, and cervix, respectively. The uterus is homogeneously hypoechoic. The AP diameter of the cervix is equal to that of the fundus, and this gives the uterus a tubular shape. (Used with permission from Dr. Neil Fernandes.)

During childhood, the uterus measures 2.5 to 4 cm and is tubular as a result of the cervix and fundus becoming equal size. The ovaries increase in size as childhood progresses, and volumes range from 2 to 4 cm3 (Ziereisen, 2005).

Puberty marks the normal physiologic transition from childhood to sexual and reproductive maturity. With puberty, primary sexual characteristics of the hypothalamus, pituitary, and ovaries initially undergo an intricate maturation process. This maturation leads to the complex development of secondary sexual characteristics involving the breast, sexual hair, and genitalia, in addition to a limited acceleration in body growth. Each landmark of hormonal and anatomic change during this time represents a spectrum of what is considered “normal.”

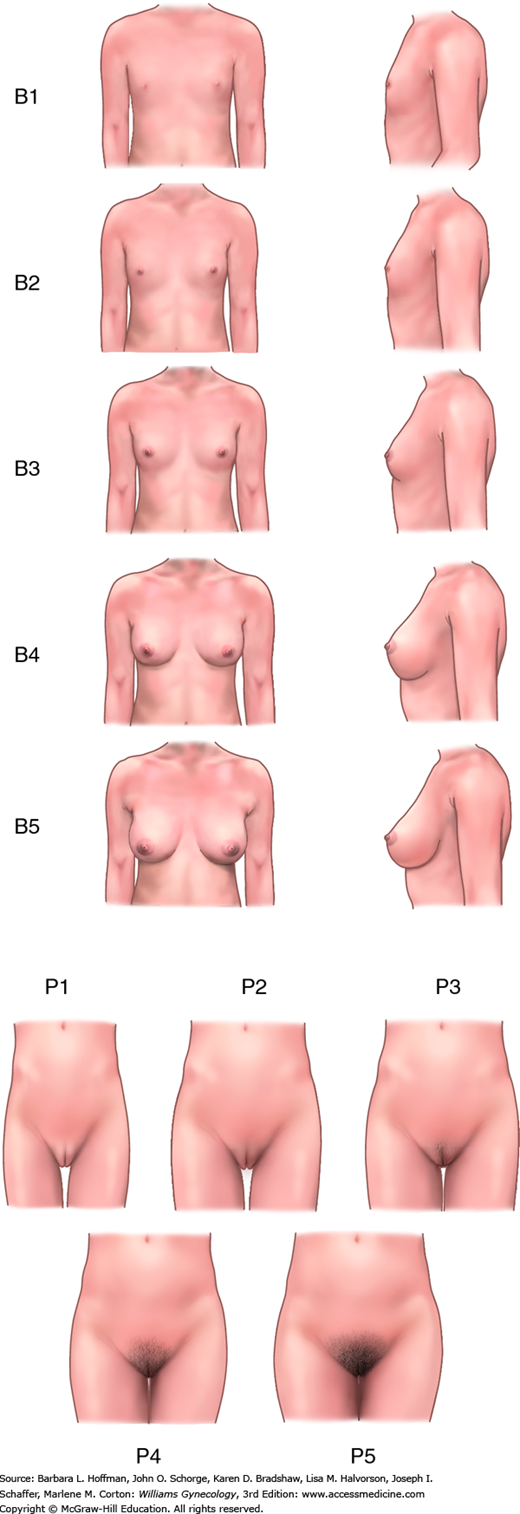

Marshall and Tanner (1969) recorded breast and pubic hair development in 192 English schoolgirls and created the Tanner stages to describe pubertal development (Fig. 14-3). Initial pubertal changes begin between ages 8 and 13 years in most North American females (Tanner, 1985). Changes before or after are categorized as either precocious puberty or delayed puberty and warrant evaluation. In most girls, breast budding, termed thelarche, is the first physical sign of puberty and begins at approximately age 10 years (Aksglaede, 2009; Biro, 2006). In a minority, pubic hair growth, known as pubarche, develops first. Following breast and pubic hair growth, adolescents undergo an accelerated increase in height, termed a growth spurt, during a 3-year span from ages 10.5 to 13.5 years.

Since these original population studies, U.S. girls have trended to start thelarche and menarche earlier. Differences in onset timing are also related to race and higher body mass index (BMI) (Biro, 2013; Rosenfield, 2009). For example, higher BMI correlates with earlier pubertal development. The mean age of menarche in white girls is 12.7 years and 6 months earlier, or 12.1, in black girls (Tanner, 1973).

GYNECOLOGIC EXAMINATION

An adolescent who has reached the age of 18 may consent to medical examination and treatment. Prior to this age, individual state laws govern whether minors can give their own consent for certain kinds of health care. Some examples include: emergency contraception, substance abuse, or sexually transmitted disease treatment. Every state has laws allowing minors to consent to care if they are emancipated, living apart from their parents, or pregnant. The Guttmacher Institute publishes an overview of Minors’ Consent Law regularly at www.agi-usa.org.

A routine yearly examination of a child by her pediatrician generally includes a brief examination of the breasts and external genitalia. Congenital anomalies that are visible externally, such as imperforate hymen, may be identified. Alternatively, if parent or child has a specific complaint regarding vulvovaginal pain, rash, bleeding, discharge, or lesions, a gynecologic examination is directed toward the area of concern.

A parent or guardian should be present at the examination. This allows the child to understand that the examination is sanctioned. Moreover, clinicians can use this opportunity to inform a parent regarding findings and potential treatment. They can also emphasize the concept of inappropriate genital touching by others and parental notification if this occurs. In mid-to-late adolescence, however, a patient may prefer, for privacy reasons, not to be examined with a parent present.

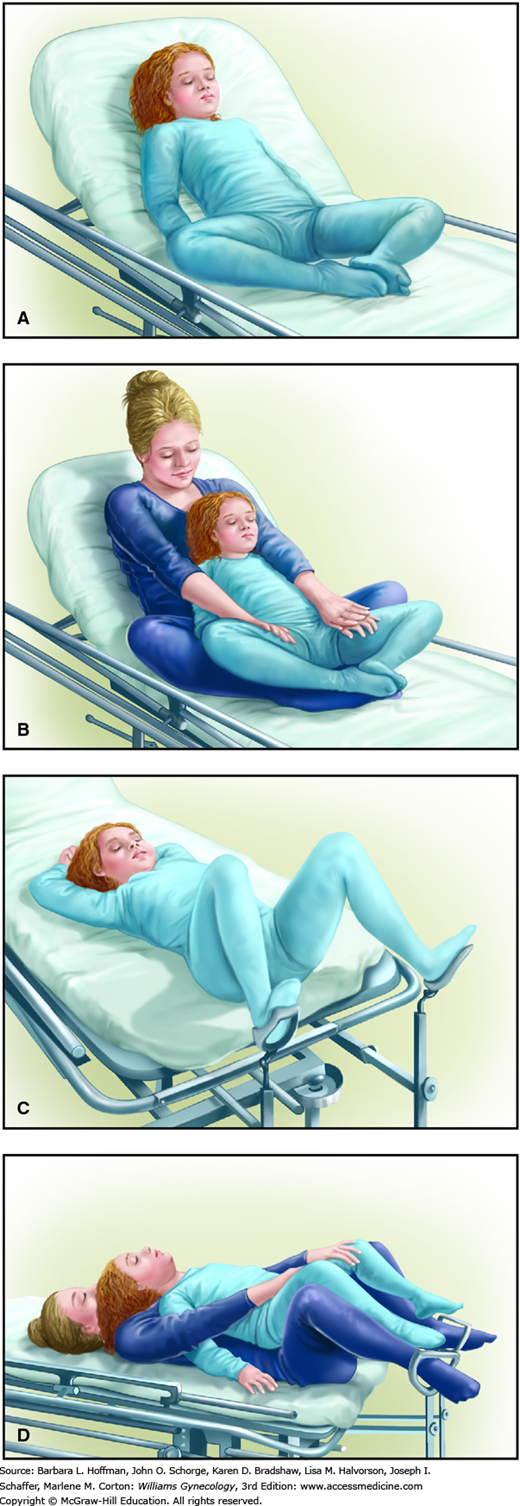

“Child-friendly” objects or pictures and distracting conversation can ease fears and aid examination. Similarly, using an anatomically appropriate doll to explain the steps may decrease anxiety. The examination begins with a less-threatening approach of checking the ears, throat, heart, and lungs. Breasts are inspected. The external genital examination is best performed with the child in a frog-leg or knee-chest position to improve visualization. Occasionally, the patient may feel more comfortable sitting in a parent’s lap. Sitting on a chair or examination table, the parent allows the child’s legs to straddle the parent’s thighs (Fig. 14-4).

Once the child is optimally positioned, each labium may be gently held with a thumb and forefinger and pulled toward the examiner and laterally. In this manner, the introitus, hymen, and lower portion of the vagina are inspected (Fig. 14-5). An internal examination is rarely necessary unless a foreign body, tumor, or vaginal bleeding is suspected. This evaluation is best accomplished under general anesthesia. Vaginoscopy may be performed using a hysteroscope or cystoscope to provide illumination as well as irrigation. During vaginoscopy, normal saline is used as the distention medium (Fig. 14-6). The labia majora are manually approximated to occlude the vagina and achieve vaginal distention.

LABIAL ADHESION

Adhesion between the labia minora begins as a small posterior midline fusion, which is usually asymptomatic. This fusion may remain an isolated minor finding or may progress toward the clitoris to completely close the vaginal orifice. Also termed labial agglutination, this adhesion develops in 1 to 5 percent of prepubertal girls and in approximately 10 percent of female infants within the first year of life (Berenson, 1992; Christensen, 1971).

The cause of labial adhesion is unknown, although hypoestrogenism is implicated. This fusion typically develops in a low-estrogen environment. Namely, it is seen in infants and young girls and tends to undergo spontaneous resolution at puberty (Jenkinson, 1984). Additionally, erosion of the vulvar epithelium is implicated in some cases of labial adhesion. For example, adhesion can be associated with lichen sclerosus, with herpes simplex viral infection, and with vulvar trauma following sexual abuse (Berkowitz, 1987).

The diagnosis is made visually. The labia majora appear normal, whereas the labia minora are fused with a distinct thin line of demarcation or raphe between them (Fig. 14-7). Extensive agglutination may leave only a ventral pinhole meatus between the labia. Located immediately beneath the clitoris, this small opening may lead to urinary dribbling as urine pools behind the adhesion. In these cases, urinary tract infection or urethritis can develop.

Treatment varies according to the degree of scarring and symptoms. In many instances, if the patient is asymptomatic, no intervention is necessary as the adhesion will typically resolve spontaneously with the rise of estrogen levels at puberty. Extensive adhesion with urinary symptoms, however, will require estrogen cream therapy. Estradiol (Estrace) cream or conjugated equine estrogen (Premarin) cream is applied to the fine, thin raphe twice daily for 2 weeks, followed by daily applications for an additional 2 weeks. A generous pea-sized amount of cream is placed with a finger or cotton-tipped applicator onto the raphe. With each application, gentle outward traction is exerted on the labia majora to help separate the adhesion. Similarly, light pressure may also be applied with the cotton applicator itself, as tolerated. After adhesion separation, a petroleum jelly (Vaseline) or vitamins A and D ointment (A&D ointment) may be applied nightly for 6 months to decrease the risk of recurrence. If the adhesion reforms during the subsequent months or years, the process may be similarly repeated. Occasionally, with overuse of estrogen cream, local irritation, vulvar pigmentation, and minor breast budding may develop, at which time topical treatment is discontinued. These side effects are reversible once treatment is halted. Alternatively, the use of 0.05-percent betamethasone cream applied twice daily for 4 to 6 weeks is another topical option (Mayoglou, 2009; Meyers, 2006).

Manual separation of labial adhesion in an outpatient setting without analgesia is painful and thus generally not advised. In addition, recurrence is much more common. However, if the adhesion persists despite consistent use of estrogen cream, then labia minora separation may be attempted several minutes after applying 5-percent lidocaine ointment to the adhesion raphe.

If separation is not easily accomplished or tolerated, surgical separation is recommended in an operating room under general anesthesia as an outpatient procedure. Midline division of the fused labia, also termed introitoplasty, uses an electrosurgical fine tip and does not require suturing. To prevent repeated agglutination after surgery, an estrogen cream is applied nightly for 2 weeks. This is followed by an emollient cream nightly for at least 6 months.

CONGENITAL ANATOMIC ANOMALIES

Several anatomic and müllerian abnormalities present in early adolescence as obstructions to menstrual outflow. Described in Chapter 18, those most commonly presenting with outlet obstruction include imperforate hymen, transverse vaginal septum, cervical and vaginal agenesis with an intact uterus, obstructed (non-communicating) uterine horn, and the OHVIRA syndrome (obstructed hemivagina with ipsilateral renal agenesis) (Smith, 2007). These are often diagnosed in an adolescent with primary amenorrhea and cyclic pain. Notably, an adolescent with OHVIRA or with an obstructed uterine horn will have menses, but these often become increasingly painful over 6 to 9 months.

VULVITIS

Vulvar inflammation may develop in isolation or in association with vaginitis. Allergic and contact dermatitis are common, whereas atopic dermatitis (eczema) and psoriasis are less frequent sources of itching and rash. With allergic and contact dermatitis the underlying pathophysiology varies, but the clinical appearance is usually similar. Vesicles or papules form on bright-red, edematous skin. However, in chronic cases, scaling, skin fissuring, and lichenification may be seen. In response, information regarding the degree of hygiene and continence and exposure to potential skin irritants is sought.

Typical offending agents include bubble baths and soaps, laundry detergents, fabric softeners and dryer sheets, bleach, and perfumed or colored toilet paper (Table 4-1). Topical creams, lotions, and ointments used to soothe an area may also be an irritant to some children. For most, removing the offending agent and encouraging once- or twice-daily sitz baths is sufficient. These baths consist of placing two tablespoons of baking soda in warm water and soaking for 20 minutes. If itching is severe, an oral medication may be prescribed, such as hydroxyzine hydrochloride (Atarax) 2 mg/kg/d divided in four doses. Alternatively, a 2.5-percent topical hydrocortisone ointment can be applied twice daily for 1 week. Aside from chemical irritants, children can also develop diaper dermatitis from urine and stool exposure. Corrective measures keep the skin dry by more frequent diaper changes, or they create a moisture barrier by application of emollient creams, such as Vaseline or A&D ointment.

Vulvitis may also be caused by lichen sclerosus. With this, the vulva displays hypopigmentation; atrophic, parchment-like skin; and occasional fissuring. Lesions are usually symmetrical and may form an “hourglass” appearance around the vulva and perianal areas (Fig. 14-8). Occasionally, the vulva develops dark purple vulvar ecchymoses, which may bleed. Over time, if left untreated, the periclitoral area may scar, the labia minora may become attenuated, and the posterior fourchette may fissure and bleed.

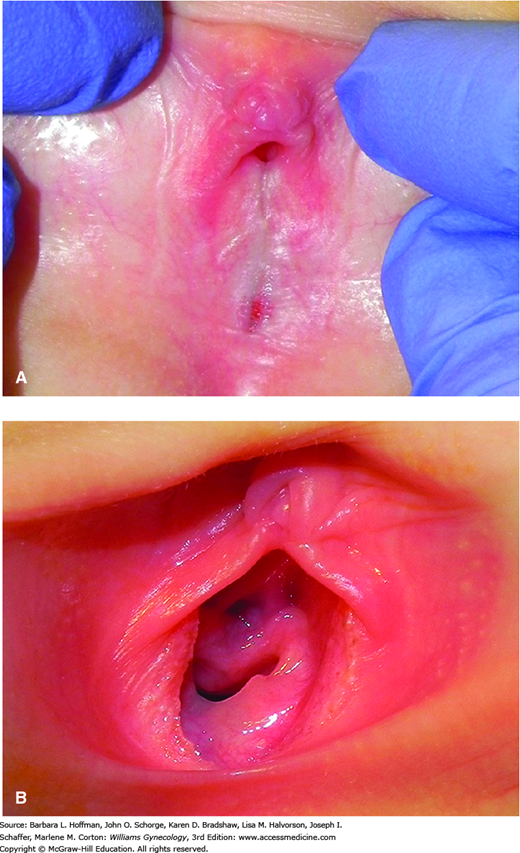

FIGURE 14-8

Lichen sclerosus before and after treatment. A. Findings include thin, parchment-like skin on the labia majora, ecchymoses on the labia minora and majora, and mild disease on the perianal skin. Involvement of both the vulva and perinal skin gives a figure-of-eight shape to affected areas. B. Skin texture and ecchymoses improved following treatment. (Used with permission from Dr. Mary Jane Pearson.)

Similar to labial adhesion, lichen sclerosus can develop concurrently with hypoestrogenism or with inflammation. Lichen sclerosus more commonly affects postmenopausal women and carries risks for vulvar malignancy. This association is not found in affected pediatric patients. The exact pathophysiology of lichen sclerosus is unknown, although an autoimmune process is suspected given its association with Graves thyroiditis, vitiligo, and pernicious anemia. Twin and cohort studies suggest a genetic role (Meyrick Thomas, 1986; Sherman, 2010).

Patients may complain of intense itching, discomfort, bleeding, excoriations, and dysuria. Diagnosis typically relies on visual inspection. However, rarely, a vulvar biopsy may be indicated in children if the classic skin changes are absent.

Treatment consists of topical corticosteroid cream such as 2.5-percent hydrocortisone, applied nightly to the vulva for 6 weeks. If improvement is noted, the dose may be lowered to 1-percent hydrocortisone and continued for 4 to 6 weeks. Thereafter, petroleum-based ointment use and strict attention to hygiene are recommended. Severe cases require a more potent corticosteroid such as 0.05-percent clobetasol propionate (Temovate), applied twice daily for 2 weeks. This initial dosing is followed by an individualized regimen, which slowly tapers the dose to a once-weekly bedtime application. The long-term prognosis for childhood lichen sclerosus is unclear. Although some cases resolve at puberty, small case series suggest that as many as 75 percent of affected children have disease that persists or recurs following puberty (Berth-Jones, 1991; Powell, 2002; Smith, 2009).

Some common infectious organisms that may cause prepubertal vulvitis include group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus, Candida species, and pinworms. With group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus, the vulva and introitus may be bright “beefy” red, and symptoms include dysuria, vulvar pain, pruritus, or bleeding. In most cases, vulvovaginal culture and clinical setting typically lead to diagnosis. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus is treated with an oral first-generation penicillin or cephalosporin or other appropriate antibiotic for 2 to 4 weeks.

Candidiasis is rare in prepubertal girls. It more often develops during the first year of life, after a course of antibiotics, or in females with juvenile diabetes or immunocompromise. A reddened, raised rash with well-demarcated borders and occasional satellite lesions is typical. Microscopic examination of a vaginal sample prepared with 10-percent potassium hydroxide (KOH) will help identify hyphae (Fig. 3-6). For treatment, antifungal creams such as clotrimazole, miconazole, or butoconazole are applied to the vulva twice daily for 10 to 14 days or until the rash clears.

Enterobius vermicularis, also known as pinworm, can create intense vulvar itching. Nocturnal pruritus results from an intestinal infection with these 1-cm-long threadlike white worms that often exit the anus at night. Inspecting this area with a flashlight at night, parents may identify worms perianally. The “Scotch-tape test” entails pressing a piece of cellophane tape to the perianal area in the morning, affixing the tape to a slide, and visualizing parasite eggs by microscopy. Treatment is albendazole (Albenza) 200 to 400 mg in a single-dose chewable tablet.

VULVOVAGINITIS

Several months after birth, as estrogen levels wane, the vulvovaginal epithelium becomes thin and atrophic. As a result, the vulva and vagina are more susceptible to irritants and infections until puberty, and vulvovaginitis is a common prepubertal problem. Three fourths of vulvovaginitis cases in this age group are nonspecific, with culture results yielding “normal flora.” Alternatively, several infectious agents, discussed subsequently, may be identified.

With nonspecific vulvovaginitis, the pathogenesis is not well defined, but known instigating factors are included in Table 14-1. Symptoms include itching, vulvar redness, discharge, dysuria, and odor. Most children and those adolescents who are not sexually active tolerate speculum examination poorly. But a vaginal swab for bacterial culture can be comfortably obtained. In cases of nonspecific vulvovaginitis, cultures typically only isolate normal vaginal flora. Culture results that reveal bowel flora suggest contamination with fecal aerobes. Treatment attempts to correct the underlying cause. Itching and inflammation may be relieved with a low-dose topical corticosteroid such as hydrocortisone, 1 or 2.5 percent. Occasionally, severe itching can lead to a secondary bacterial infection that requires oral antibiotics. Oral agents often selected are amoxicillin, an amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid combination, or a similar cephalosporin given during a 7- to 10-day course.

|

Infectious vulvovaginitis often presents with a malodorous, yellow or green purulent discharge, and vaginal cultures are routinely obtained in these cases. The respiratory pathogen group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus is the most common specific infectious agent found in prepubertal females and is isolated from 7 to 20 percent of girls with vulvovaginitis (Pierce, 1992; Piippo, 2000). Treatment of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus consists of amoxicillin, 40 mg/kg, taken orally three times daily for 10 days. Less frequently, other respiratory pathogens found include: Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree