INTRODUCTION

Pain in the lower abdomen and pelvis is a common complaint. But, pain is subjective and often ambiguous, and thus, difficult to diagnose and treat. To assist, clinicians ideally understand the mechanisms underlying human pain perception, which involves complex physical, biochemical, emotional, and social interactions. Providers are obligated to search for organic sources of pain, but equally important, avoid overtreatment of a condition that is minor or short lived.

PAIN PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Pain is a protective mechanism meant to warn of an immediate threat and to prompt withdrawal from noxious stimuli. Pain is usually followed by an emotional response and inevitable behavioral consequences. These are often as important as the pain itself. The mere threat of pain may elicit emotional responses even in the absence of actual injury.

When categorized, pain may be considered somatic or visceral depending on the type of afferent nerve fibers involved. Additionally, pain is described by the physiologic steps that produce it and can be defined as inflammatory or neuropathic (Kehlet, 2006). Both categorizations are helpful for diagnosis and treatment.

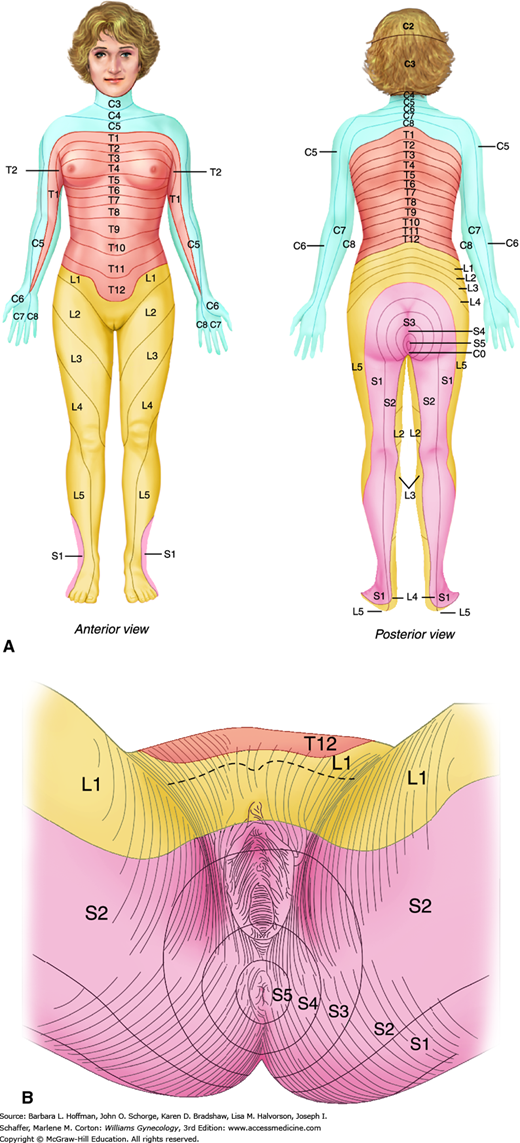

Somatic pain stems from nerve afferents of the somatic nervous system, which innervates the parietal peritoneum, skin, muscles, and subcutaneous tissues. Somatic pain is typically sharp and localized. It is found on either the right or left within dermatomes that correspond to the innervation of involved tissues (Fig. 11-1).

In contrast, visceral pain stems from afferent fibers of the autonomic nervous system, which transmits information from the viscera and visceral peritoneum. Noxious stimuli typically include stretching, distention, ischemia, necrosis, or spasm of abdominal organs. The visceral afferent fibers that transfer these stimuli are sparse. Thus, the resulting diffuse sensory input leads to pain that is often described as a generalized, dull ache.

Visceral pain often localizes to the midline because visceral innervation of abdominal organs is usually bilateral (Flasar, 2006). As another attribute, visceral afferents follow a segmental distribution, and visceral pain is typically localized by the brain’s sensory cortex to an approximate spinal cord level that is determined by the embryologic origin of the involved organ. For example, pathology in midgut organs, such as the small bowel, appendix, and caecum, causes perceived periumbilical pain. In contrast, disease in hindgut organs, such as the colon and intraperitoneal portions of the genitourinary tract, causes midline pain in the suprapubic or hypogastric area (Gallagher, 2004).

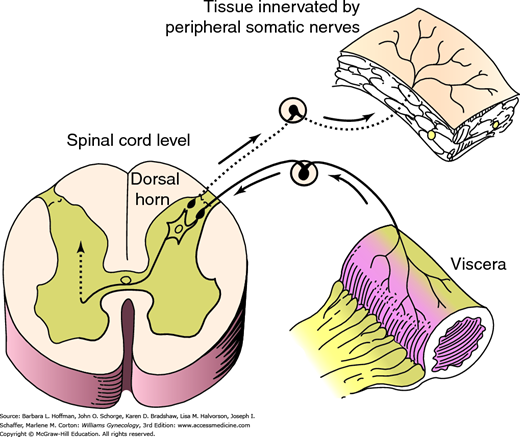

Visceral afferent fibers are poorly myelinated, and action potentials can easily spread from them to adjacent somatic nerves. As a result, visceral pain may at times be referred to dermatomes that correspond to these adjacent somatic nerve fibers (Giamberardino, 2003). In addition, both peripheral somatic and visceral nerves often synapse in the spinal cord at the same dorsal horn neurons. These neurons, in turn, relay sensory information to the brain. The cortex recognizes the signal as coming from the same dermatome regardless of its visceral or somatic nerve origin. This phenomenon is termed viscerosomatic convergence and makes it difficult for a patient to distinguish internal organ pain from abdominal wall or pelvic floor pain (Fig. 11-2) (Perry, 2003).

FIGURE 11-2

Viscerosomatic convergence. Pain impulses originating from an organ may affect dorsal horn neurons that are synapsing concurrently with peripheral somatic nerves. These impulses may then be perceived by the brain as coming from a peripheral somatic source such as muscle or skin rather than the diseased viscera. (Reproduced with permission from Howard FM, Perry CP, Carter JE, et al (eds): Pelvic Pain: Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.)

Viscerosomatic convergence explains the dermatomal distribution of some visceral pain. In contrast, direct intraspinal neuronal reflexes permit transmission of visceral nociceptive input to other pelvic viscera (viscerovisceral reflex), to muscle (visceromuscular reflex), and to skin (viscerocutaneous reflex). These intraspinal reflexes may explain why patients with endometriosis or interstitial cystitis manifest other pain syndromes such as vestibulitis, pelvic floor myalgia, or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Thus, unless the underlying chronic visceral pain source is identified and properly treated, referred pain and secondary pain syndromes may not be successfully eliminated (Perry, 2000).

With acute pain, noxious stimuli such as a knife cut, burn, or crush injury activate sensory pain receptors, more formally termed nociceptors. Action potentials travel from the periphery to dorsal horn neurons in the spinal cord. Here, reflex arcs may lead to immediate muscle contraction, which removes and protects the body from harm. Additionally, within the spinal cord, sensory information is augmented or dampened and may then be transmitted to the brain. In the cortex, it is recognized as pain (Janicki, 2003). After an acute stimulus is eliminated, nociceptor activity quickly diminishes.

If tissues are injured, then inflammation usually follows. Body fluids, along with inflammatory proteins and cells, are called to the injury site to limit tissue damage. Because cells and most inflammatory proteins are too large to cross normal endothelium, vasodilation and increased capillary permeability are required features of this response. Chemical mediators of this process are prostaglandins, which are released from the damaged tissue, and cytokines, which are produced in white blood cells and endothelial cells. Cytokines include interleukins, tissue necrosis factors, and interferons. These sensitizing mediators are released into affected tissues and lower the conduction threshold of nociceptors. This is termed peripheral sensitization. Similarly, neurons within the spinal cord and/or brain display increased excitability, termed central sensitization. As a result, within inflamed tissues, the perception of pain is increased relative to the strength of the external stimulus (Kehlet, 2006). Normally, as inflammation decreases and healing ensues, the increased sensitivity to stimuli and thus the perception of pain subsides.

In some individuals, sustained noxious stimuli can lead to persistent central sensitization and to a permanent loss of neuronal inhibition. As a result, a decreased threshold to painful stimuli remains despite resolution of the inciting stimuli (Butrick, 2003). This persistence characterizes neuropathic pain, which is felt to underlie many chronic pain syndromes. During central sensitization, neurons within spinal cord levels above or below those initially affected may eventually become involved. This phenomenon results in chronic pain that may be referred across several spinal cord levels. In addition, some evidence suggests that chronic pain states are also associated with regional brain morphology changes in regions known to regulate pain. This has been described as maladaptive central nervous system (CNS) plasticity in response to prolonged nociceptive input (As-Sanie, 2012). The concept of neuropathic pain helps explain in part why many patients with chronic pain have discomfort disproportionately greater than the amount of coexistent disease found.

Thus, in assessing patients with chronic pain, a clinician may find an ongoing inflammatory condition. In these cases, inflammatory pain dominates, and treatment is directed at resolving the underlying inflammatory condition. However, for many patients, evaluation may reveal no or minimal current pathology. In these cases, pain is neuropathic, and treatment thus focuses on management of pain symptoms themselves.

ACUTE PAIN

The definition of acute lower abdominal pain and pelvic pain varies based on duration, but in general, discomfort is present less than 7 days. The sources of acute lower abdominal and pelvic pain are extensive, and a thorough history and physical examination can aid in narrowing the list (Table 11-1). With acute pain, a timely and accurate diagnosis is the goal and ensures the best medical outcome. Thus, although history and examination are described separately here, in clinical settings they often are performed almost simultaneously for optimal results.

| Gynecologic | |

| PID Tuboovarian abscess Ectopic pregnancy Incomplete abortion Prolapsing leiomyoma | Dysmenorrhea Mittelschmerz Ovarian mass Ovarian torsion Obstructed outflow tract |

| Gastrointestinal | |

| Gastroenteritis Colitis Appendicitis Diverticulitis Constipation | Inflammatory bowel disease Irritable bowel disease Obstructed small bowel Mesenteric ischemia Malignancy |

| Urologic | |

| Cystitis Pyelonephritis | Urinary tract stone Perinephric abscess |

| Musculoskeletal | |

| Hernia | Abdominal wall trauma |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Peritonitis Diabetic ketoacidosis Herpes zoster Opiate withdrawal | Sickle cell crisis Vasculitis Abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture |

In addition to a thorough medical and surgical history, a verbal description of the pain and its associated factors is essential. For example, duration can be informative, and pain with abrupt onset may be more often associated with organ torsion, rupture, or ischemia. The nature of pain may add value. Patients with acute pathology involving pelvic viscera may describe visceral pain that is midline, diffuse, dull, achy, or cramping. One example is the midline periumbilical pain of early appendicitis.

Patients may repeatedly shift or roll to one side to find a comfortable position.

The underlying pelvic pathology may extend from the viscera to inflame the adjacent parietal peritoneum. In these cases, sharp somatic pain is described, which is localized, often unilateral, and focused to a specific corresponding dermatome. Again using appendicitis as an example, the classic migration of pain to the site of peritoneal irritation in the right lower quadrant illustrates acute somatic pain. In other instances, sharp, localized pain may originate, not from the parietal peritoneum, but from pathology in specific muscles or in isolated areas of skin or subcutaneous tissues. In either instance, with somatic pain, patients classically rest motionless to avoid movement of the affected peritoneum, muscle, or skin.

Colicky pain may reflect bowel obstructed by adhesion, neoplasia, stool, or hernia. It can also stem from increased bowel peristalsis in those with irritable or inflammatory bowel disease or infectious gastroenteritis. Alternatively, colic may follow forceful uterine contractions with the passage of products of conception, pedunculated submucous leiomyomas, or endometrial polyps. Last, stones in the lower urinary tract may cause spasms of pain as they are passed.

Associated symptoms may also direct diagnosis. For example, absence of dysuria, hematuria, frequency, or urgency will exclude urinary pathology in most instances. Gynecologic causes are often associated with vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, or amenorrhea. Alternatively, exclusion of diarrhea, constipation, or gastrointestinal bleeding lowers the probability of gastrointestinal (GI) disease.

Vomiting complaints, however, are less informative, although the temporal relationship of vomiting to the pain may be helpful. In the acute surgical abdomen, if vomiting occurs, it usually follows as a response to pain and results from vagal stimulation. This vomiting is typically severe and develops without nausea. For example, vomiting has been found in approximately 75 percent of adnexal torsion cases (Descargues, 2001; Huchon, 2010). Thus, the acute onset of unilateral pain that is severe and associated with a tender adnexal mass in a patient with vomiting alerts one to the increased probability of adnexal torsion. Conversely, if vomiting is noted prior to the onset of pain, a surgical abdomen is less likely (Miller, 2006).

In general, well-localized pain or tenderness, persisting for longer than 6 hours and unrelieved by analgesics, has an increased likelihood of acute peritoneal pathology.

Examination begins with patient observation during initial questioning. Her general appearance, including facial expression, diaphoresis, pallor, and degree of agitation, often indicates the urgency of the clinical condition.

Elevated temperature, tachycardia, and hypotension will prompt an expedited evaluation, as the risk for intraabdominal pathology increases with their presence. Constant, low-grade fever is common in inflammatory conditions such as diverticulitis and appendicitis, and higher temperatures may be seen with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), advanced peritonitis, or pyelonephritis.

Pulse and blood pressure evaluation ideally assess orthostatic changes if intravascular hypovolemia is suspected. A pulse increase of 30 beats per minute or a systolic blood pressure drop of 20 mm Hg or both, between lying and standing after 1 minute, is often reflective of hypovolemia. If noted, establishment of intravenous access and fluid resuscitation may be required prior to examination completion. Notably, certain neurologic disorders and medications, such as tricyclic antidepressants or antihypertensives, may also produce similar orthostatic blood pressure changes.

Abdominal examination is essential. Visual inspection of the abdomen focuses on prior surgical scars, which may increase the possibility of bowel obstruction from postoperative adhesions or incisional hernia. Additionally, abdominal distention may be seen with bowel obstruction, perforation, or ascites. After inspection, auscultation may identify hyperactive or high-pitched bowel sounds characteristic of bowel obstruction. Hypoactive sounds, however, are less informative.

Palpation of the abdomen systematically explores each abdominal quadrant and begins away from the area of indicated pain. Peritoneal irritation is suggested by rebound tenderness or by abdominal rigidity due to involuntary guarding or reflex spasm of the adjacent or involved abdominal muscles.

Pelvic examination in general is performed in reproductive-aged women, as gynecologic pathology and pregnancy complications are a common pain source in this age group. The decision to pursue this pelvic examination in geriatric and pediatric patients is based on clinical information.

Of findings, purulent vaginal discharge or cervicitis may reflect PID. Vaginal bleeding can stem from pregnancy complications, benign or malignant reproductive tract neoplasia, or acute vaginal trauma. Leiomyomas, pregnancy, and adenomyosis are common causes of uterine enlargement, and the latter two may also create uterine softening. Cervical motion tenderness reflects peritoneal irritation and can be seen with PID, appendicitis, diverticulitis, and intraabdominal bleeding. A tender adnexal mass may reflect ectopic pregnancy, tuboovarian abscess, or ovarian cyst with torsion, hemorrhage, or rupture. Alternatively, a tender mass may reflect an abscess of nongynecologic origin such as one involving the appendix or colon diverticulum.

Rectal examination can add information regarding the source and size of pelvic masses and the possibility of colorectal pathologies. Stool guaiac testing for occult blood, although less sensitive when not performed serially, is still warranted in many patients (Rockey, 2005). Those with complaints of rectal bleeding, painful defecation, or significant changes in bowel habits are examples.

In emergency departments, women with acute pain may experience waits between their initial assessment and subsequent testing. For these patients, literature supports early administration of analgesia. Fears that analgesia will mask patient symptoms and hinder accurate diagnosis have not been supported (McHale, 2001; Pace, 1996). Thus, barring significant hypotension or drug allergy, morphine sulfate may be administered judiciously in these situations.

Despite benefits from a thorough history and physical examination, the sensitivity of these two in diagnosing abdominal pain is low (Gerhardt, 2005). Thus, laboratory and diagnostic testing are typically required. In women with acute abdominal pain, pregnancy complications are common. Thus, either urine or serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) testing is recommended in those of reproductive age without prior hysterectomy. Complete blood count (CBC) can identify hemorrhage, both uterine and intraabdominal, and can assess the possibility of infection. Urinalysis can be used to evaluate possible urolithiasis or cystitis. In addition, microscopic evaluation and culture of vaginal discharge may add support to clinically suspected cases of PID.

In women with acute pelvic pain, several imaging options are available. However, transvaginal and transabdominal pelvic sonography are preferred modalities if an obstetric or gynecologic cause is suspected (Andreotti, 2011). Sonography provides a high sensitivity for detection of structural pelvic pathology. It is widely available, can usually be obtained quickly, requires little patient preparation, is relatively noninvasive, and avoids ionizing radiation. Disadvantageously, examination quality is affected by the skill and experience of the sonographer.

In most cases, the transvaginal approach offers superior resolution of the reproductive organs. Transabdominal sonography may still be necessary if the uterus or adnexal structures are significantly large or if they lie beyond the transvaginal probe’s field of view. Color Doppler imaging during sonography permits evaluation of the vascular qualities of pelvic structures. In women with acute pain, the addition of Doppler studies is particularly useful if adnexal torsion or ectopic pregnancy is suspected (Twickler, 2010). Less common causes of acute pain amenable to sonographic diagnosis are perforation of the uterine wall by an intrauterine device (IUD) or hematometra caused by menstrual outflow obstruction from müllerian agenesis anomalies. For these, 3-dimensional (3-D) transvaginal sonography has become invaluable (Bermejo, 2010; Moschos, 2011).

Computed tomography (CT) and multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) are increasingly used to evaluate acute abdominal pain in adults. CT offers a global examination that can identify numerous abdominal and pelvic conditions, often with a high level of confidence (Hsu, 2005). Compared with other imaging tools, it has superior performance in identifying GI and urinary tract causes of acute pelvic and lower abdominal pain (Andreotti, 2011). For example, noncontrasted renal colic CT has largely replaced conventional intravenous pyelography to search for ureteral obstruction. For appendicitis, one study found that the false-positive diagnosis rate among adults decreased from 24 to 3 percent from 1996 to 2006. Investigators noted that this decrease correlated with the increased rate of CT use during the same interval (Raman, 2008). Appendiceal perforation also decreased from 18 to 5 percent. Considering that the false-positive diagnosis of appendicitis in women is as high as 42 percent, this certainly represents an improvement in clinical outcomes. For evaluation of GI abnormalities such as appendicitis, the combination of both oral and intravenous contrast is preferred.

In addition to its high sensitivity, CT has several advantages for most nongynecologic disorders. It is extremely fast; is not perturbed by gas, bone, or obesity; and is not operator dependent. Disadvantages include occasional unavailability, high cost, inability to use contrast media in patients who are allergic or have renal dysfunction, and exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation (Leschka, 2007).

The debate regarding CT safety and possible overuse is ongoing (Brenner, 2007). Of major concern is the potential increased cancer risk directly attributable to ionizing radiation, which is estimated to be even higher in younger patients and women (Einstein, 2007). Radiation doses from CT are generally considered to be 100 to 500 times those from conventional radiography (Smith-Bindman, 2010). Investigators in a large multicenter analysis found the median effective radiation dose from a multiphase abdomen and pelvic CT scan was 31 mSv, and this correlates with a lifetime attributable risk of four cancers per 1000 patients (Smith-Bindman, 2009). By way of comparison, health care workers are generally limited to 100 mSv over 5 years with a maximum of 50 mSv allowed in any given year (Fazel, 2009). But, in the acute clinical setting, CT imaging benefits frequently outweigh these risks.

In some instances, plain film radiography is selected. Although its sensitivity is low for most gynecologic conditions, it still may be informative if bowel obstruction or perforation is suspected (Leschka, 2007). Dilated loops of small bowel, air-fluid levels, free air under the diaphragm, or the presence or absence of colonic gas are all significant findings when attempting to differentiate between a gynecologic and GI cause of acute pain.

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is becoming an important tool for women with acute pelvic pain if initial sonography is nondiagnostic. Common reasons for noninformative sonographic evaluations include patient obesity and pelvic anatomy distortion secondary to large leiomyomas, müllerian anomalies, or exophytic tumor growth. As a first-line tool, MR imaging is often selected for pregnant patients, for whom ionizing radiation exposure should be limited. However, for most acute disorders, it provides little advantage over 3-D sonography or CT (Bermejo, 2010; Brown, 2005). Lack of availability can be a disadvantage after hours, on weekends, or in smaller hospitals and emergency departments.

Operative laparoscopy is the primary treatment for suspected appendicitis, adnexal torsion, ectopic pregnancy, and ruptured ovarian cyst associated with ongoing symptomatic hemorrhage. Moreover, diagnostic laparoscopy may be useful if no pathology can be identified by conventional diagnostics. However, in stable patients with acute abdominal pain, noninvasive testing is typically exhausted before this approach is considered (Sauerland, 2006).

The decision to perform a surgical procedure for acute pelvic pain can be challenging. If the patient is clinically stable, the decision can be made in a timely manner, with appropriate evaluation and consultation completed preoperatively. In a less stable patient with signs of peritoneal irritation, possible hemoperitoneum, organ torsion, shock, and/or impending sepsis, the decision to operate is made decisively unless there are overwhelming clinical contraindications to immediate surgery.

CHRONIC PAIN

Persistent pain may be visceral, somatic, or mixed in origin. As a result, it may take several forms in women that include chronic pelvic pain (CPP), dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, dysuria, musculoskeletal pain, intestinal cramping, or vulvodynia. Each of these forms is described here except for vulvodynia, discussed in Chapter 4. The list of pathologies that may underlie these symptoms is extensive and includes both psychological and organic disorders (Table 11-2). Moreover, pathology in one organ can commonly lead to dysfunction in adjacent systems. As a result, a woman with chronic pain may have more than one cause of pain and overlapping symptoms. A comprehensive evaluation of multiple organ systems and psychologic state is essential for complete treatment.

| Gynecologic | ||

| Endometriosis Adenomyosis Leiomyomas Abdominal adhesions Endometrial/endocervical polyps Ovarian mass Adnexal cysts | Reproductive tract cancer Pelvic muscle trigger points Intrauterine contraceptive device Outflow tract obstruction Ovarian retention syndrome Ovarian remnant syndrome Pelvic organ prolapse | Chronic PID Chronic endometritis Vestibulitis Pelvic congestion syndrome Broad ligament herniation Chronic ectopic pregnancy Postoperative peritoneal cysts |

| Urologic | ||

| Chronic UTI Detrusor dyssynergia Urinary tract stone | Urethral syndrome Urethral diverticulum Urinary tract cancer | Interstitial cystitis Radiation cystitis |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| IBS Constipation Diverticular disease | Colitis Gastrointestinal cancer | Celiac disease Chronic intermittent bowel obstruction |

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Hernias Muscular strain Faulty posture | Levator ani syndrome Fibromyositis Spondylosis | Vertebral compression Disc disease Coccydynia Peripartum pelvic pain |

| Neurologic | ||

| Neurologic dysfunction Pudendal neuralgia Piriformis syndrome | Abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment Neuralgia of iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal, lateral femoral cutaneous, or genitofemoral nerves | Spinal cord or sacral nerve tumor |

| Miscellaneous | ||

| Psychiatric disorders Physical or sexual abuse Shingles |

CHRONIC PELVIC PAIN

This common gynecologic problem has an estimated prevalence of 15 percent in reproductive-aged women (Mathias, 1996). No definition is universally accepted. However, many investigators define chronic pelvic pain as: (1) noncyclic pain that persists for 6 or more months; (2) pain that localizes to the anatomic pelvis, to the anterior abdominal wall at or below the umbilicus, or to the lumbosacral back or buttocks; and (3) pain sufficiently severe to cause functional disability or lead to medical intervention (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2010).

Causes of CPP fall within a broad spectrum, but endometriosis, symptomatic leiomyomas, and IBS are often diagnosed. Of these, endometriosis is a frequent cause, but it typically is also associated with cyclic symptoms. It is discussed fully in Chapter 10. Chronic pain secondary to leiomyomas is described in Chapter 9.

The pathophysiology of CPP is unclear in many patients, but evidence supports a significant association with neuropathic pain, described earlier. CPP shows increased association with IBS, interstitial cystitis, and vulvodynia, which are considered by many to be chronic visceral pain syndromes stemming from neuropathic pain (Janicki, 2003).

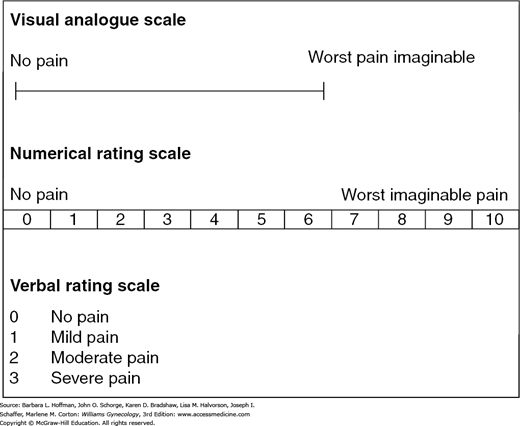

More than with many other gynecologic complaints, a detailed history and physical examination are integral to diagnosis. A pelvic pain questionnaire can be used initially to obtain information. One example is available from the International Pelvic Pain Society and may be accessed at: http://www.pelvicpain.org/docs/resources/forms/History-and-Physical-Form-English.aspx. Additionally, a body silhouette diagram can be provided to patients for them to mark specific sites of pain. The McGill Pain Questionnaire and Short Form combines a list of pain descriptors with a body map for patients to mark pain sites (Melzack, 1987). Pain scales can also quantify discomfort and include visual analogue scales (VAS) and verbal descriptor scales (VDS) (Fig. 11-3). At minimum, the series of questions found in Table 11-3 may provide valuable information. As noted, many of these questions focus on gynecologic, surgical, and psychologic risk factors.

|

First, of gynecologic factors, CPP is more common in women than men and is often worsened by stress and menstruation. Also, pregnancy and delivery can be traumatic to neuromuscular structures and have been linked with pelvic organ prolapse, pelvic floor muscle myofascial pain syndromes, and symphyseal or sacroiliac joint pain. In addition, injury to the ilioinguinal or iliohypogastric nerves during Pfannenstiel incision for cesarean delivery may lead to lower abdominal wall pain even years after the initial injury (Whiteside, 2003). Following delivery, recurrent, cyclic pain and swelling in the vicinity of a cesarean incision or within an episiotomy suggests endometriosis within the scar itself (Fig. 10-3). In contrast, in a nulliparous woman with infertility, pain may stem more often from endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, or PID.

Second, prior abdominal surgery increases a woman’s risk for pelvic adhesions, especially if infection, bleeding, or large areas of denuded peritoneal surfaces were involved. Adhesions were found in 40 percent of patients who underwent laparoscopy for chronic pelvic pain suspected to be of gynecologic origin (Sharma, 2011). The incidence of adhesions increases with the number of prior surgeries (Dubuisson, 2010). Last, certain disorders persist or commonly recur, and thus information regarding prior surgeries for endometriosis, adhesive disease, or malignancy are sought.

Of psychologic risk factors, CPP and sexual abuse are significantly associated (Jamieson, 1997; Lampe, 2000). A metaanalysis by Paras and associates (2009) demonstrated that sexual abuse is linked with an increased lifetime diagnosis rate of functional bowel disorders, fibromyalgia, psychogenic seizure disorder, and CPP. Additionally, for some women, chronic pain is an acceptable means to cope with social stresses. Thus, patients are questioned regarding domestic violence and satisfaction with family relationships. Furthermore, an inventory of depressive symptoms is essential, as depression may cause or result from CPP (Tables 13-3 and 13-4). Other conditions bearing similarities to CPP include fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, temporomandibular disorder, and migraine. These are referred to as functional somatic syndromes, and CPP can be comorbid with each of these (Warren, 2011).

In a woman with chronic pain, even routine examination may be extremely painful. In those with neuropathic pain, mere light touch may elicit discomfort. Therefore, examination proceeds slowly to allow relaxation between each step. Moreover, a patient is reassured that she may ask for the examination to be halted at any time. Terms used to describe examination findings include allodynia and hyperesthesia, among others. Allodynia is a painful response to a normally innocuous stimulus, such as a cotton swab. Hyperalgesia is an extreme response to a painful stimulus.

Women with intraperitoneal pathology may compensate with changes in posture. Such adjustments can create secondary musculoskeletal sources of pain. Alternatively, musculoskeletal structures may be the site of referred pain from these organs (Table 11-4). Thus, careful observation of a woman’s posture and gait is integral.

| Structure | Innervation | Referred Pain Site(s) |

| Hip | T12–S1 | Lower abdomen; anterior medial thigh; knee |

| Lumbar ligaments, facets/disks | T12–S1 | Low back; posterior thigh and calf; lower abdomen; lateral trunk; buttock |

| Sacroiliac joints | L4–S3 | Posterior thigh; buttock; pelvic floor |

| Abdominal muscles | T5–L1 | Abdomen; anteromedial thigh; sternum |

| Pelvic and back muscles | ||

| Iliopsoas | L1–L4 | Lateral trunk; lower abdomen; low back; anterior thigh |

| Piriformis | L5–S3 | Low back, buttock; pelvic floor |

| Pubococcygeus | S1–L4 | Pelvic floor; vagina; rectum; buttock |

| Obturator internal/external | L3–S2 | Pelvic floor; buttock; anterior thigh |

| Quadratus lumborum | T12–L3 | Anterior lateral trunk; anterior thigh; lower abdomen |

Initially, a woman is examined while standing. Posture is evaluated anteriorly, posteriorly, and laterally. Anteriorly, symmetry of the anterior superior iliac spines (ASISs), umbilicus, and weight bearing is evaluated. If one leg bears most of the weight, the nonbearing leg is often externally rotated and slightly flexed at the knee. Next, the anterior abdominal wall and inguinal areas are inspected for abdominal wall or femoral hernias, described on page 267. Inspection of the perineum and vulva with the patient standing may identify varicosities. These are often asymptomatic or may cause superficial discomfort. Such varicosities may coexist with internal pelvic varicosities, the underlying cause of pelvic congestion syndrome.

Posteriorly, inspection for scoliosis and of horizontal stability of the shoulders, gluteal folds, and knee creases is completed. Asymmetry may reflect musculoskeletal disorders.

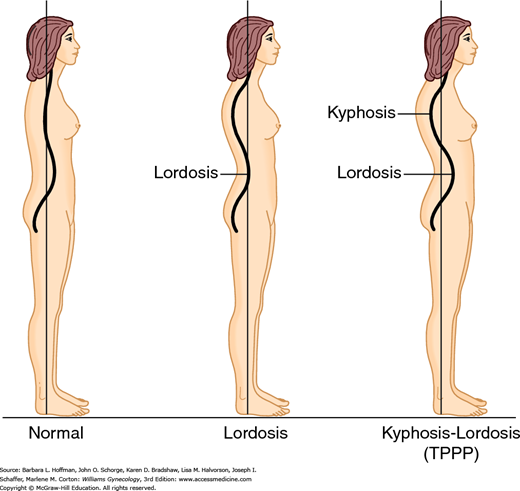

Lateral visual examination searches for lordosis and concomitant kyphosis. This combination has been noted in some women with CPP and termed typical pelvic pain posture (TPPP) (Fig. 11-4) (Baker, 1993). Also, abnormal tilt of the pelvic bones can be assessed by simultaneously placing an open palm on each side between the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) and the ASIS. Normally, the ASIS lies one-quarter inch below the level of the PSIS, and greater distances may suggest abnormal tilt. Pelvic tilt may be associated with hip osteoarthritis and other orthopedic problems (Labelle, 2005; Yoshimoto, 2005).

Any observed mobility limitation can be informative. Thus, a patient is asked to bend forward at the waist. Limitation in forward flexion may reflect primary orthopedic disease or adaptive shortening of back extensor muscles. This shortening is seen frequently in women with chronic pain and TPPP. In such cases, patients are unable to bend over at the waist to create the normal convex curve.

Muscle weakness may also indicate orthopedic disease. A Trendelenburg test, in which a patient is asked to balance on one foot, can indicate dysfunction of hip abductor muscles or hip joint. With a positive test, when a woman elevates a leg by flexing the hip, the ipsilateral iliac crest droops.

Gait is evaluated by having the patient walk across the room. An antalgic gait, known as a limp, refers to a gait that minimizes weight bearing on a lower limb or joint and indicates a higher probability of musculoskeletal pain.

A patient is next invited to sit on the examining table. Myofascial pain syndrome may involve pelvic floor muscles and often leads to a patient shifting weight to one buttock or sitting toward a chair’s front edge.

With the patient supine, the anterior abdominal wall is evaluated for abdominal scars. These may be sites of hernia or nerve entrapment or may indicate a risk for intraabdominal adhesive disease. Auscultation for bowel sounds and bruits follows. Increased bowel activity may reflect irritable or inflammatory bowel diseases. Bruits prompt investigation for vascular pathology.

While supine, a woman is asked to demonstrate with one finger the point of maximal pain and then encircle the total surrounding area of involvement. Superficial palpation of the anterior abdominal wall by a clinician may reveal sites of tenderness or knotted muscle that may reflect nerve entrapment or myofascial pain syndrome. Moreover, pain with elevation of the head and shoulders while tensing the abdominal wall muscles, Carnett sign, is typical of anterior abdominal wall pathology. Conversely, if the source of pain originates from inside the abdominal cavity, discomfort usually decreases with such elevation (Thomson, 1991). Moreover, Valsalva maneuver during head and shoulder elevation may display diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle or hernias. Diastasis recti can be differentiated in most cases from a ventral hernia. Specifically, with diastasis, the borders of the rectus abdominis muscle can be palpated bilaterally along the entire length of the protrusion. Last, deep palpation of the lower abdomen may identify pathology originating from pelvic viscera. Dullness to percussion or a shifting fluid wave may indicate ascites.

Mobility is also evaluated. In most cases, a woman can elevate her leg 80 degrees from the horizontal toward her head, termed a straight leg test. Pain with leg elevation may be seen with lumbar disc, hip joint, or myofascial pain syndromes. Additionally, symphyseal pain with this test may indicate laxity in the symphysis pubis or pelvic girdle. Both the obturator and iliopsoas tests may indicate myofascial pain syndromes involving these muscles or disorders of the hip joint. With the obturator test, a supine patient brings one knee into 90 degrees of flexion while the same foot remains planted. The ankle is held stationary, but the knee is gently pulled laterally and then medially to assess for tenderness. With the iliopsoas test, a supine woman with legs extended attempts to flex each hip separately against downward resistance from the examiner’s hand placed on the ipsilateral anterior thigh. If pain is described with hip flexion, the test result is positive.

Pelvic examination begins with inspection of the vulva for generalized changes and localized lesions. Vulvar erythema often reflects infectious vulvitis, described in Chapter 3, or vulvitis stemming from dermatoses (Chap. 4). Vulvar skin thinning may reflect lichen sclerosus or atrophic changes. The vestibular area is also examined. Erythema of the vestibule, with or without punctate lesions, may indicate vestibulitis. Following this inspection, systematic pressure point palpation of the vestibule, as shown in Figure 4-1, is completed using a small cotton swab to assess for pain (allodynia). Last, the anocutaneous reflex, as described in Chapter 24, may also be performed to assess pudendal nerve integrity.

Prior to speculum examination, a single digit systematically evaluates the vagina. Pain elicited from pressure beneath the urethra may indicate urethral diverticulum. Pain with anterior vagina palpation under the trigone can reflect interstitial cystitis. Systematic sweeping pressure against the pelvic floor muscles along their length may identify isolated taut muscle knots from pelvic floor myofascial syndrome. Of these muscles, the pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and obturator internus muscles can usually be reached with a vaginal finger (Fig. 11-5). Next, insertion points of the uterosacral ligaments are palpated. Nodularity is highly suggestive of endometriosis, and palpation may reproduce dyspareunia symptoms. Cervical motion tenderness may be noted with acute and chronic PID. If pain follows gentle movement of the coccyx, then articular disease of the coccyx, termed coccydynia, is suspected. The importance of pelvic examination sequence cannot be overstated, as information from single-digit examination may be lost if preceded by bimanual examination.

Bimanual assessment of the uterus may reveal a large uterus, often with an irregular contour, due to leiomyomas. Globular enlargement with softening is more typical of adenomyosis. Immobility of the uterus may follow scarring from endometriosis, PID, malignancy, or adhesive disease from prior surgeries. Adnexal palpation may reveal tenderness or mass. Tenderness alone may reflect endometriosis, diverticular disease, or pelvic congestion syndrome. Adnexal mass evaluation is outlined in Chapter 9.

Rectal examination and rectovaginal palpation of the rectovaginal septum is included. Palpation of hard stool or hemorrhoids may indicate GI disorders, whereas nodularity of the rectovaginal septum may be found with endometriosis or neoplasia. Myofascial tenderness involving the puborectalis and coccygeus muscles can be noted by sweeping the index finger with pressure across these muscles. Last, stool testing for occult blood may be performed during digital rectal examination at the initial visit. Alternatively, home test kits for occult blood are available and discussed in Chapter 1.

For women with CPP, diagnostic testing may add valuable information. Results from urinalysis and urine culture can indicate stones, malignancy, or recurrent infection of the urinary tract as pain sources. Thyroid disease can affect physiologic functioning and may be found in those with bowel or bladder symptoms. Thus, serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels are commonly assayed. Diabetes can lead to neuropathy, and glucose levels can be assessed with urinalysis or serum testing.

Radiologic imaging and endoscopy may be informative, and of these, transvaginal sonography is widely used by gynecologists to evaluate CPP. Sonography of the pelvic organs may reveal endometriomas, leiomyomas, ovarian cysts, dilated pelvic veins, and other structural lesions. In those with suspected pelvic congestion syndrome, transvaginal color Doppler ultrasound is often a primary diagnostic tool (Phillips, 2014). With sonography, patients can be imaged standing, if necessary, and while performing a Valsalva maneuver to accentuate vasculature distention. However, despite its applicability for many gynecologic disorders, sonography has poor sensitivity in identifying endometriotic implants or most adhesions. Of other modalities, CT or MR imaging often adds little additional information to that obtained with sonography. These may be selected if sonography is uninformative or if anatomy is greatly distorted.

In those with bowel symptoms, barium enema may indicate intraluminal or external obstructive lesions, malignancy, and diverticular or inflammatory bowel disease. However, flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy may offer more information because colonic mucosa can be directly inspected and biopsied if necessary.

Cystoscopy, laparoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy may each be employed, and patient symptoms will dictate their use. In those with symptoms of chronic pain and urinary symptoms, cystoscopy is often advised. If GI complaints predominate, then flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy may be warranted. For many women with no obvious cause of their CPP, laparoscopy is performed. Importantly, intraoperative explanations for CPP are common despite normal preoperative examinations (Cunanan, 1983; Kang, 2007). Laparoscopy allows direct identification and, in many cases, treatment of intraabdominal pathology. Therefore, laparoscopy is considered by many to be a “gold standard” for CPP evaluation (Sharma, 2011).

One laparoscopic approach to CPP is performed under local anesthesia with the patient conscious and available for questioning regarding sites of pain (Howard, 2000; Swanton, 2006). Termed conscious pain mapping, this technique has resulted in more targeted treatment and improved postoperative pain scores. However, its clinical use to date has been limited.

In many women with CPP, an identifying source is found and treatment is dictated by the diagnosis. However, in other cases, pathology may not be identified, and treatment is directed toward dominant symptoms.

Treatment of pain typically begins with oral analgesics such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) listed in Table 10-1. NSAIDs are particularly helpful if inflammatory states underlie the pain. Acetaminophen is a widely used and effective analgesic despite having no significant antiinflammatory properties. Of note, dosing recommendations from the Food and Drug Administration (2011) limit the maximum total daily dose of acetaminophen to 4 g.

If satisfactory relief is not achieved, then opioid analgesics such as codeine or hydrocodone may be added (Table 42-2). Importantly, opioid maintenance therapy for CPP is considered only if all other reasonable pain control attempts have failed and if benefits outweigh harms (Chou, 2009; Howard, 2003). Opioids are most effective and least addictive if given on a scheduled basis and at doses that adequately relieve pain. If pain persists, stronger opioids such as morphine, methadone, fentanyl, oxycodone, and hydromorphone can replace milder ones. However, this is balanced against side effects. Close and regular surveillance is essential, and consultation with pain management experts may be beneficial (Baranowski, 2014; Chou, 2009). Unlike classic opioids, tramadol hydrochloride has a mild central opioid effect but also inhibits serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake.

Estrogen support is integral to endometriosis. Thus, an empiric trial of sex-steroid hormone suppression may be considered, especially in those with coexistent dysmenorrhea or dyspareunia and who lack dominant bladder or bowel symptoms. As discussed in Chapter 10, combination oral contraceptives, progestins, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, and certain androgens are effective options.

For many, CPP represents neuropathic pain, and therapy with antidepressants or anticonvulsants has been extrapolated from treatment of such pain in other disorders. Tricyclic antidepressants reduce neuropathic pain independent of their antidepressant effects (Saarto, 2010). Moreover, antidepressants are a logical choice, as clinically significant depression is commonly comorbid with pain. Amitriptyline (Elavil) and its metabolite nortriptyline (Pamelor) have the best documented efficacy for neuropathic and nonneuropathic pain syndromes (Table 11-5) (Bryson, 1996). Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors do not have strong evidence to support their efficacy for CPP (Lunn, 2014). Of anticonvulsants, gabapentin and carbamazepine are most commonly used to reduce neuropathic pain (Moore, 2014; Wiffen, 2014).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree