Fig. 16.1

Ultrasonographic scan of myomas during pregnancy: (a) a subserous myoma of 2 cm in a pregnant at 5 weeks of pregnancy, with the eco Doppler enhancing peripheral myoma vascularization; (b) a posterior intramural corporal myoma of 3 cm of diameter at 8 weeks of pregnancy, with the eco Doppler enhancing placental and peripheral myoma vascularization; (c) an anterior cervical myoma in patient at 6 weeks of pregnancy; (d) a large myoma previo of 9 cm of diameter, at 18 weeks of pregnancy

Less common complication of myoma in pregnancy are disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, cervical pregnancy, spontaneous hemoperitoneum, uterine inversion, uterine torsion, urinary retention in the first trimester; about fetal complications related to myoma in pregnancy, the literature showed limb reduction anomalies and head and body deformities related to fetal compression [1, 3, 6–8, 10, 13].

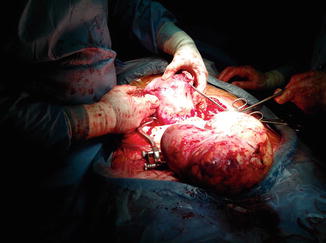

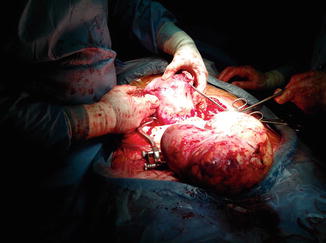

Operations on the uterus during the CS, except for excision of pedunculated myomas (Figs. 16.2 and 16.3), are traditionally discouraged for the aforementioned reasons, as uncontrolled and profuse bleeding, that may lead to a severe anemia, puerperal infection and to hysterectomy.

Fig. 16.2

A large fundal pedunculated myoma in pregnancy of 10 cm of diameter, to be removed during cesarean section

Fig. 16.3

A lateral giant fundal pedunculated myoma in pregnancy of 22 cm of diameter, removed during cesarean section

Uterine fibroids, a part the risk of spontaneous abortion, preterm labor, placental abruption and post partum hemorrhage, have been associated with a 10–40 % obstetric complication rate premature labor and adverse obstetric outcomes during and after delivery [3, 5, 6, 10, 13, 14].

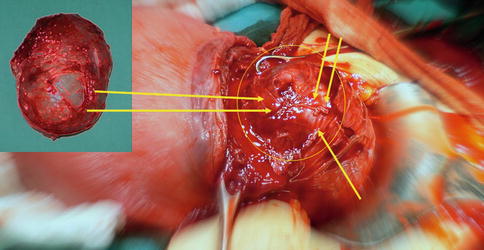

The greatest risks of cesarean myomectomy frequently results from lack of knowledge of the presence of uterine myoma during unexpected or scheduled CS, or from a wrong knowledge of myoma location. Myomas lead to dystocia as tumor previa (Fig. 16.4) or, when located in the lower uterine segment (LUS), they cause extreme technical difficulties during closure of the hysterotomy when leaving the fibroid in situ.

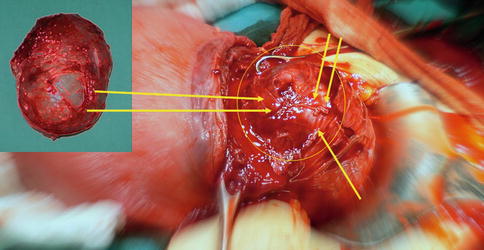

Fig. 16.4

A tumor previa in pregnancy of 8 cm of diameter, located on lower uterine segment; surgeons performed the hysterotomy on the top of myoma, removed fetus and proceed to enucleate myoma previa (in the box in the upper left)

Also for the above reasons, myomectomy performed during pregnancy still remains a high-risk operation.

Later on, with the accumulated experience and lack of major complications coupled with the fact that no evidence-based contraindications could be found in the literature, we were inspired to develop our own technique with our research group, and to use it also for large fibroids that were located away from the LUS.

The only absolute contraindication for cesarean myomectomy stated in the literature is intra-surgical uterine hypotony/atony, following the delivery of the fetus [15–19].

Uterine Modified Anatomy and Physiology with Myomas in Pregnancy

Pregnancy induces profound anatomical and physiological changes to uterus and its vascularization, all factors to consider before starting an operation during pregnancy. So, once diagnosis of myoma is confirmed by ultrasonography, management of myoma encountered during CS poses a therapeutic dilemma: how myomas should be better managed during pregnancy, labor or delivery? For example in case of myomas located next to the LUS. In such cases, and in order to deliver the baby, the obstetrician is faced with the emergency decision of making the incision through or near the myoma, removing it, or choosing the classical longitudinal incision to deliver the baby while avoiding cutting through or near the myoma.

The surgeon has to make decisions if myomectomy is really indicated during cesarean delivery or it should be delayed for some months after delivery.

During pregnancy, uterine enlargement involves marked hypertrophy of the muscle cells and a progressive increase in the uteroplacental blood flow ranging from approximately 450–650 mL/min near term [20, 21].

This increased blood flow is mediated primarily by means of vasodilatation. The uterine arteries’ diameter doubles by 20 weeks of gestation and concomitant mean Doppler velocimetry is increased eightfold [22].

Thus, any surgical procedure performed on or around the uterus has the potential of causing severe hemorrhage and, for this reason, uterine myomectomy during cesarean section has consistently been discouraged, in the past years, as a high-risk procedure.

In cases of a small pedunculated subserous fibroid attached to the uterus with a small pedicle, myomectomy is relatively easy, with clamping, cutting and suturing of the myoma pedicle.

On the contrary, resection of an intramural myoma is inadvisable and contraindicated during cesarean section by some obstetric textbooks [23, 24], due to the risk of profuse uncontrolled bleeding that could lead to hysterectomy. In such books, the authors remark that myomas often undergo a remarkable involution after delivery and they may even become pedunculated, making myomectomy (if necessary) easier and safer as a postpartum intervention than at the time of cesarean section [24, 25].

Furthermore, because of bizarre nuclear changes at pathologists examination, myomas enucleated during pregnancy or delivery can be often interpreted as leiomyosarcoma, thus leading to unnecessary anxiety and fear. In the scientific literature there are also several data and lately larger studies indicating myomectomy during CS or even during pregnancy as a probably safer procedure than previously believed.

Literature on Cesarean Myomectomy

In 1989, Burton et al. [7] were probably the first to report the procedure of a myomectomy during pregnancy and cesarean section (CS). They reviewed an 8-year experience with surgical management of leiomyomata during pregnancy at the Los Angeles County Women’s Hospital. Five women underwent explorative laparotomy only, six had a myomectomy during pregnancy, and three had a hysterectomy; one patient aborted after surgery. Thirteen other women had incidental myomectomies at cesarean delivery; one of these had an intraoperative hemorrhage. No other complications were reported.

During 1997–2001, Ben Rafael et al. [26] evaluated prospectively the surgical outcome of a planned myomectomy during CS in cases where the fibroids were either known to be large enough to require surgery at a later stage, or when the fibroid led to malpresentations. The outcome investigated parameters were: type of anesthesia, type of incision, intraoperative blood loss, need for blood transfusion, intra- or postoperative complications, and length of hospital stay. Thirty-nine myomas were removed from 32 patients in 15 elective and 17 emergency procedures. Indications for CS were obstetrical (breech presentation, more than one previous CS, among others) in most cases. The indications in the other women were: myomas causing dystocia as tumor previa, fibroid degeneration and intractable pain, and uterine cavity penetration in cases of previous myomectomies. Ninety percent of the myomas were subserous or intramural, and 10 % submucous. The average size (largest dimension) was 6 cm (1.5–20), with 26 myomas measuring >3 cm, and 11 >6 cm. Four CS (12.5 %) were classical, and the rest low-segmental. Most of the operations were performed under regional anesthesia (spinal block). The difference in hemoglobin and hematocrit levels before and 12 h after the operation was significantly lower in patients who underwent cesarean myomectomies, compared to those who underwent CS avoiding myomectomy (p < 0.05), yet only four patients required a blood transfusion. Two patients underwent repeated surgeries: one with two large myomas and excessive bleeding, and the other due to a subcutaneous hematoma. No hysterectomy was required. Six patients had postpartum fever (18.7 %). The average duration of hospitalization was 5.7 days, with five patients requiring more than 6 days of hospitalization. There was no correlation between complications or duration of hospital stay and patient age, gravidity, parity or indication for CS [26].

Michalas et al. [27] performed a myomectomy on a 31-year-old primigravida during the 15th week of pregnancy due to a large, 23 cm diameter myoma. At the 39th week of pregnancy, during the CS, eight fibroids obstructing the lower part of the uterus were removed. There were no maternal or fetal complications.

Çelik et al. [28], in his study conclusions, reported that myomectomy could be also safe if performed during pregnancy. Five pregnant women with myomas requiring surgical removal because of severe pain underwent a myomectomy at a median gestational age of 17.8 ± 3.4 weeks. The mean size of the myomas was 14.0 ± 3.8 cm. No major surgical and postoperative complications were observed and all the pregnancies continued to term.

Reporting surgical experiences of the last century, other authors reported their experience with cesarean myomectomies, as Hsieh et al. [29] who retrospectively reviewed 47 incidental cesarean myomectomies. The procedure added only 11 min to the operating time, 112 mL to the operative blood loss, and extended the hospital stay by about 1.5 days. There was no wound infection or serious morbidity.

Dimitrov et al. [30] conducted a prospective study in Bulgaria to evaluate myomectomy during CS as “a routine method”. Their study group comprised of 21 cases that underwent myomectomies during CS, and were compared to a control group of 162 consecutive CS without having undergone myomectomies. They found that myomectomy during CS increased the blood loss by 10 %. Analysis of the cases with severe hemorrhage showed that they were related to other placental disorders (abruptio placentae and placenta previa) as the main cause of the increased blood loss. There were no postoperative complications.

Omar et al. [31] reported two cases with large, uterine myomas, situated in the anterior aspect of the lower segment, complicating pregnancy at term. A myomectomy in both instances facilitated delivery of the fetus through the lower segment, enabling vaginal delivery in subsequent pregnancies.

Brown et al. [15] from Jamaica retrospectively analyzed the records of 32 women: 16 underwent cesarean myomectomy and were compared to 16 cases of CS chosen as the first normal CS occurring after each cesarean myomectomy. The myomectomy was always performed after delivery of the fetus and after the administration of oxytocin. Diluted oxytocin was also injected into the myoma’s capsule to facilitate hemostasis. The results indicated that the patients who underwent a cesarean myomectomy were significantly older (p < 0.0001), but there was no statistical difference in parity between the two groups. The median number of myomas found was two (range: 1–6). The mean blood loss was similar among the two groups: 403 ± 196 ml in the myomectomy group vs. 356 ± 173 ml in the regular CS. No significant difference between the groups was observed in relation to hemoglobin levels, need for blood transfusion, febrile morbidity or the length of hospital stay.

Ehigiegba et al. [16] prospectively assessed the intra- and post-operative complications of cesarean myomectomies in 25 pregnancies. Patients with known fibroids were required to provide their consent for a possible cesarean myomectomy. Leiomyomas in the anterior uterine wall (cervical, body or fundal) were removed through the CS incision when possible, otherwise other incision(s) were performed. Nineteen patients (76 %) underwent emergency CS after trial of labor, while 6 (24 %) had elective CS. A total of 84 fibroids were removed. In most women there were only 1–2 leiomyomas, but in 1 patient 22 myomas (!) were removed; 57 % of the myomas were intramural, 35.7 % subserous of which only 1 % was pedunculated. Anemia was apparent in 60 % of patients but only five patients (20 %) required blood transfusion. No single hysterectomy was indicated. Three patients (12 %) had subsequent pregnancies, two of whom had normal vaginal deliveries and one underwent a repeat CS.

The largest report by Roman and Tabsh [32] compared the results of caesarean myomectomies to “no touch” CS. They retrospectively evaluated 111 women who underwent a cesarean myomectomy and 257 women with documented fibroids who underwent CS alone. The two groups were similar with respect to median age, median parity, median gestational age and median size of the fibroids. Most patients in both groups underwent low transverse incision CS. In 86 % of the patients the fibroids were incidental findings, while in the rest symptoms such as pain, dystocia and unusual appearance of the myoma dictated its removal. The incidence of hemorrhage in the study group was 12.6 %, compared with 12.8 % in the control group (p = 0.95). There were no statistically significant increases in the incidence of postpartum fever, operating time, and length of postpartum stay. The size of the fibroid did not appear to affect the incidence of hemorrhage. After stratifying the procedures by type of fibroid removed, intramural myomectomy was found to be associated with a 21.2 % incidence of hemorrhage, compared with 12.8 % in the control group, but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.08). No patient in either group required hysterectomy or embolization following the operation. A similar study by Kaymak et al. [33] on 40 patients undergoing a cesarean myomectomy compared to 80 patients with untouched myomas during CS also showed that performing a myomectomy during CS does not increase the surgical and postoperative complication rate.

Although all the above mentioned studies and reports indicate a good outcome after a cesarean myomectomy, or even after performing a myomectomy during pregnancy, one should remember that hemorrhage can still occur and lead to severe consequences.

Literature showed even a case of maternal death following cesarean myomectomy, caused by massive hemorrhage and subsequent coagulopathy by Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation [34].

Recently authors suggested the use of intraoperative blood salvage in pregnants with planned cesarean myomectomy, particularly when massive intraoperative hemorrhage is expected [35]. These authors presented a preliminary experience with intraoperative blood salvage during cesarean section in four patients with fibroids, two of which scheduled for cesarean myomectomy. The volume of salvaged blood was 450 and 700 ml, respectively. The authors did not encountered any complications caused by blood salvage itself.

Exacoustos et al. [5] reported nine myomectomies performed during cesarean delivery. Of these, three were complicated by severe hemorrhage, indicating hysterectomy. The authors emphasized the role of various ultrasound findings in identifying women at risk for myoma-related complications: the size of the myoma, its position, location, relationship to the placenta, and echogenic structure.

Several recent studies have described techniques that can minimize blood loss at cesarean myomectomy, including uterine tourniquet [36] bilateral uterine artery ligation [37] and the use of electrocautery [38].

Serious issue regarding use of those techniques is long duration of surgery, which was 89 ± 41 min in the study of Desai et al. [39], who used uterine and ovarian artery ligation. Such a prolonged surgery can be a significant cause of postopeartive morbidity, thus influencing overall cesarean myomectomy complication rate.

However, the majority of the mentioned publications concludes that a myomectomy performed at the time of CS should not increase the risk of hemorrhage and postoperative fever and should not prolong hospital stay. In fact, cesarean myomectomy was stated as a feasible and safe procedure when performed by an experienced surgeon [15, 16, 32, 33].

Pedunculated subserous myomas can be safely removed even if of large size.

Subserous and intramural myomas that are located at the LUS can and probably should be removed and not bypassed by performing a classical incision.

Performing an elective myomectomy from other uterine locations should be considered with caution, since in most of these myomas involution will occur to an insignificant size during puerperium. Meticulous attention to hemostasis, enucleation using sharp dissection with Metzenbaum scissors, adequate approximation of the myometrium and all dead spaces to prevent hematoma formation can increase the safety of the procedure. Despite the lack of prospective and randomized studies, the retrospective investigations clearly show that the tradition that discouraged caesarean myomectomy should be reassessed. Women with known myomas undergoing elective or emergency CS should be properly informed in order to obtain their consent for the option of performing a cesarean myomectomy.

Traditional Technique of Cesarean Myomectomy

The operation should be performed, at least at the outset, by a gynecologist who is proficient in myomectomies on non-gravid uteri [40]. After delivery, the hysterotomy enables the maximal myoma exposure for its removal and the minimal myometrial damage for hysterorrhaphy. Myomectomies could be performed through a transversal or vertical incision, depending on the attitude and preferences of surgeon.

In case on myomas located near the hysterotomy, an interlocked suture is temporarily placed on the edge of the cesarean uterine incision without closure. In such cases, myomectomies are preferably performed from the edge of the cesarean section incision (for myomas located near lower uterine segment). This also facilitates working from within the uterine cavity or from the outer part of the uterus without significant bleeding from the hysterotomy. In case of fibroids located far from cesarean section incision, myomectomies are preferably performed by making a new incision above the myoma in instances where they are located in a site remote from the CS incision.

Surgeons always perform the myoma dissection from myometrium using a sharp Metzenbaum scissor. Intravenous oxytocin drip is generally given after enucleation of the fibroid (some surgeons prefer also during myomectomy). No tourniquet is used by many surgeons as routine; however this may be used to control an unexpected bleeding. Suturing of the fibroid base is traditionally performed by using two layers of interrupted sutures and a baseball-type suture is used for the serosa as a third layer [40, 41].

One important issue with myomectomy is controlling blood loss from the raw myoma beds after their removal. Blood loss is generally estimated from the suction aspiration, and from weighing swabs and drapes used during surgery. Several techniques to reduce blood loss have been studied and reported.

A randomized trial comparing vasopressin and saline injected into the serosa prior to the uterine incision showed that vasopressin is extremely effective for decreasing blood loss. In this study, 50 % of patients receiving saline required transfusion, while none of those in the vasopressin group required transfusion (13 % vs 5 % decrease in hematocrit values) [42].

To reduce bleeding after caesarean myomectomy some surgeons sometimes place tourniquets around the uterus. This is usually performed, especially for in case of placenta accreta [43, 44], by perforating a window in the broad ligament at the level of the internal cervical os bilaterally and passing a Foley catheter or red rubber catheter through the perforated windows and around the cervix and then tightening it with a clamp to constrict the uterine vessels. In combination with this, vascular clamps are generally placed on the utero-ovarian ligaments [45].

Two randomized trials compared vasopressin and tourniquet use after myomectomy.

In 1996, Fletcher et al. showed that vasopressin was associated with less blood loss and lower risk of either transfusion or blood loss of more than 1 L [46].

In 1993, Ginsberg et al. [47] noted no statistically significant difference between the groups, although their study was much smaller. No studies are available comparing tourniquet use with any tourniquet use. Study results very clearly suggest that vasopressin (usually 20 U in 50–100 mL normal saline) should be injected routinely prior to making the incision in the wall of the uterus. Whether additional use of a tourniquet decreases blood loss remains unclear. After dilute vasopressin has been injected, an incision is made through the wall of the uterus into the myoma. Once the plane between the myometrium and myoma has been defined, it is dissected bluntly and sharply until the entire fibroid is removed. As many fibroids as possible are removed through a single incision. Once the fibroids have been removed, the defect is closed in layers with delayed absorbable suture [47].

Proper placement of the incision side is frequently overlooked but is important.

In 1993, Tulandi et al. [48] studied 26 women with uteri larger than 6–8 weeks’ size. Abdominal myomectomies were performed, followed by a second-look laparoscopy 6 weeks later. Patients with incisions in the posterior wall of the uterus had a much higher likelihood of significant adhesions as measured by percentage with adhesions or American Fertility Society (AFS) adhesion score compared with patients with incisions in the fundus or anterior wall of the uterus [48].

Investigations of Cobellis et al. on scar healing at myomectomy site following cesarean section, by clinical and ultrasound investigations [49, 50], concluded that a possible cause for such observation could be the activation of immune system in pregnancy. Similar results are also suggested by Lee et al. [51], while other researchers suggested that better quality of uterine scar in such cases should enable a safe subsequent vaginal delivery, and makes scar less prone to uterine rupture [52]. Further, during surgery, surgeons need to change the hysterotomic incision. According to a study on this topic, T incision in the uterus is necessary in 0.8 % of CS in the general population [53], and this occur as a consequence of fibroids’ location on at term uterus, which requires the surgeon to change strategy of surgical steps.

One of the main indications for corporal cesarean section in literature are fibroids [54, 55]. Localization and the size of the fibroids may represent an indication for corporal cesarean section, as well documented [56–58]. Although some authors suggest cesarean myomectomy prior to the delivery of the fetus, as a method to avoid corporal cesarean section, there are cases of corporal cesarean section due to expansion of the hysterotomic incision for the fibroids’ location [59]. Investigations on cesarean myomectomy already published [55–62] does not provide the incidence of either uterine corporal or T incisions, although there are some studies and case reports describing their use, even if without sample size details.

About corporal cesarean section, Roman and Tabsh [32] reported 13 patients on 368 women with fibroids (3.53 %) delivered by corporal cesarean section, while Simsek et al. [63] have recorded on 70 patients 2 cases (2.86 %) of corporal cesarean section, and Ben Rafael et al. [26] had only 4 of 32 (12.5 %).

In some cases, cesarean myomectomy is mandatory for delivery of the fetus. Sparić et al. [59] described a case of cesarean myomectomy not decisive for fetal extraction, so the hysterotomy was needed to be expanded into a inverted T incision, even if the fetal extraction was possible only by fetal version in a pregnant with multiple fibroids. It’s also important to remember that difficulties in fetal extraction can cause iatrogenic fetal injuries, as described by Adesiyn et al. [64]. These authors reported a neonate with fracture of humerus and clavicular bone during delivery, out of 22 pregnants in their study.

Intracapsular Cesarean Myomectomy

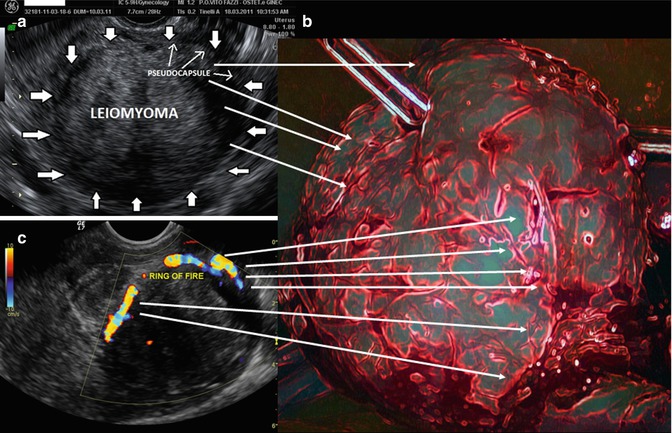

Myoma pseudocapsule is a neurovascular bundle or fibrovascular network attached to the fibroids, which separates the fibroids from the normal myometrium. At ultrasonographic exam, myoma pseudocapsule appears as a white ring around fibroid, and at echo Doppler check, it appears as a “ring of fire”, even in pregnancy (Fig. 16.5).