Cesarean Delivery

James R. Scott

T. Flint Porter

Cesarean section is the term commonly used to describe the delivery of an infant through an abdominal uterine incision. Since the words cesarean and section used together are redundant because both imply incision, cesarean delivery is preferable and is used in this chapter.

Cesarean delivery has played a major role in lowering both maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality rates during the past century. The initial purpose of the operation was to preserve the life of the mother with obstructed labor, but indications expanded over the years to include delivery for a variety of more subtle dangers to the mother or fetus. Contributing to its more frequent use is increased safety that is largely due to better surgical technique, improved anesthesia, effective antibiotics, and availability of blood transfusions.

The cesarean rates during the past decade, both in the United States and worldwide, have increased dramatically. The percentage of women in the United States delivering by cesarean increased from <5.0% in 1965 to 30.2% in 2005 and has increased 40% since 1996. It is now the most common operation performed in the United States. There are a number of reasons for this striking increase. During the 1970s and 1980s, it was thought that cesarean delivery would be the solution to numerous obstetric problems. Facing increasing medicolegal pressures, obstetricians gradually abandoned most vaginal breech and forceps deliveries, broadened the definition of intrapartum fetal distress, and liberalized the diagnosis of dystocia. Also, a greater number of older women and primigravidas, whose primary cesarean rate is higher, were having children. This escalation in cesareans also increased during the past decade as enthusiasm for vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) waned and was replaced by the more frequent use of repeat cesarean. Finally, a recent trend toward primary elective cesarean delivery requested by the mother has now become a reality in many areas of the world.

Although perinatal outcome in the United States improved during the time when the cesarean rate increased, it also improved in other countries where cesarean rates remained low. Notably, the incidence of cerebral palsy has not declined during the past 20 years, primarily because perinatal morbidity and mortality more often are a function of antepartum events, abnormal fetal growth, congenital anomalies, and premature birth.

Indications

Cesarean delivery is necessary when labor is unsafe for either the mother or fetus, when labor cannot be induced, when dystocia or fetal problems present significant risks with vaginal delivery, and when an emergency mandates immediate delivery (Table 27.1). Many indications are well accepted, a number are subjective or selectively applied in individual patients, and others are more controversial. The majority of cesareans are performed for fetal indications, a few are for only maternal reasons, and some benefit both and the mother and fetus. Repeat cesarean now accounts for more than 35% of cesarean births in the United States. Dystocia, fetal distress, breech, and other obstetric conditions are the indications for most primary cesareans cases.

Labor Contraindicated

Uterine contractions can be hazardous to the mother under certain circumstances. These include central placenta previa, previous classical uterine incision, myomectomy transecting the uterine wall, or uterine reconstruction. In these situations, labor and vaginal delivery may result in uterine rupture and hemorrhage, endangering the life or future health of the mother. Conditions where labor is dangerous to the fetus include placenta previa, velamentous insertion of the cord or other forms of vasa previa, and cord presentation. More recent indications include treatable fetal anomalies such as meningomyelocele and certain degrees of hydrocephaly.

TABLE 27.1 Common Indications for Cesarean Delivery | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Failed Induction

Conditions such as isoimmunization, diabetes mellitus, intrauterine growth restriction, and hypertensive disorders that constitute a threat to the mother or fetus often require delivery when the cervix is unfavorable for induction. If attempts to induce labor are inappropriate or unsuccessful, cesarean is the only alternative.

Dystocia

Mechanical problems involving the uterus, fetus, or birth canal or ineffective uterine contractions that result in unsuccessful progress of labor and vaginal delivery are collectively referred to as dystocia. This term encompasses a variety of commonly used clinical terms, such as failure to progress, cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD), and dysfunctional labor. It also is a relative term. For example, fetal macrosomia sometimes causes CPD, but most cesarean births for abnormal labor involve a normal-sized infant. Dystocia occasionally is caused by soft tissue tumors and abnormal fetal presentations.

Fetal Distress

Electronic fetal monitoring improves the chance of detecting fetal distress, but its inaccuracy (false-positive rate) also has contributed to the increased number of cesarean births. Many clinicians have replaced vaginal breech deliveries with cesarean delivery to avoid the risk of intrapartum asphyxia or delivery-related trauma from head entrapment and umbilical cord prolapse.

Maternal or Fetal Emergency

Maternal or fetal conditions that require immediate delivery of the baby because vaginal delivery is either impossible or inappropriate include severe placental abruption, hemorrhage from placenta previa, prolapse of the umbilical cord, active genital herpes, and impending maternal death. Each hospital and obstetrical team should have a plan in place for these acute emergencies that includes a goal for a “decision to delivery time” within 30 minutes.

Primary Elective Cesarean on Maternal Request

Cesarean delivery on maternal requests is defined as a cesarean performed for a singleton pregnancy on maternal request in the absence of any medical or obstetric indications. This is a controversial and relatively modern concept involving a number of ethical, emotional, and legal considerations. The National Institutes of Health held a State-of-the-Science Conference on Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request in March 2006. The conclusions were that there is insufficient evidence to evaluate fully the benefits and risks of elective cesarean, individualization of the decision is necessary, and women who plan on having several children should avoid maternal request deliveries. It also was recommended that pain management should not be a motivating factor, and the cesarean delivery should not be performed prior to 39 weeks unless fetal maturity is verified. Women who want to deliver by cesarean list such reasons as dread of labor, fear of pain, risk of death and fetal injury, concern about damage to the pelvic floor including later anal and urinary incontinence and sexual function, and the convenience of planning and timing the delivery. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) considers it ethical to perform a patient-choice cesarean if the physician believes that overall health of the patient and fetus is greater with cesarean than with vaginal birth. It is estimated that 4% to 18% of all cesareans worldwide are now performed because of patient choice.

Complications

Cesarean delivery is not an innocuous procedure. A variety of postpartum complications, including unexplained fever, endometritis, wound infection, hemorrhage, aspiration, atelectasis, urinary tract infection, thrombophlebitis, and pulmonary embolism, can occur in up to 25% of patients. The frequency of maternal death related to cesarean delivery varies with the institution and with the condition necessitating the procedure. Maternal mortality

rates are now <1 in 1,000 operations, and many deaths are related to the underlying maternal illness or anesthetic complications.

rates are now <1 in 1,000 operations, and many deaths are related to the underlying maternal illness or anesthetic complications.

Late maternal complications of cesarean delivery include intestinal obstruction from adhesions and dehiscence of the uterine incision in subsequent pregnancies. Both of these complications are more common with the classic incision than with a lower uterine segment incision. The incidence of placenta previa and abnormal myometrial invasion by the placenta (accreta/increta/percreta) also is increased with each successive cesarean and can cause severe and intractable hemorrhage. The incidence of placenta previa or placenta accreta progressively increases from 3% with the first cesarean to 11% with the second, 40% with the third, 61% with the fourth, and 67% with the fifth. This has become a significant problem that requires careful preoperative counseling and preparation for intrapartum management, including the possibility of hysterectomy, when these conditions exists.

Types of Cesarean Operations

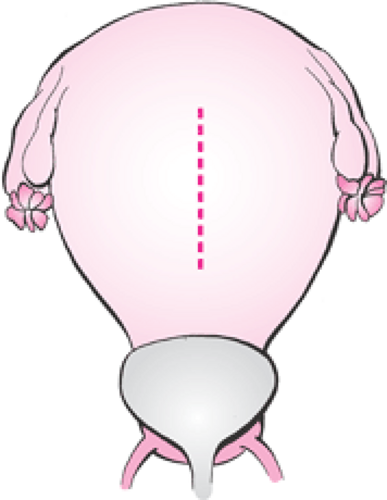

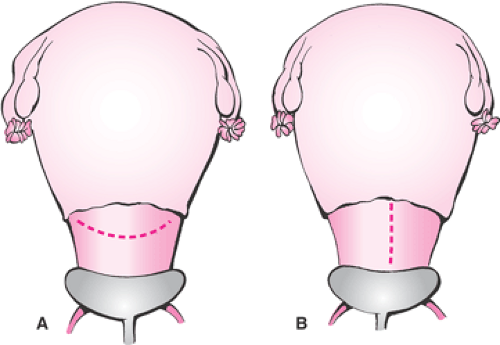

Almost all contemporary cesareans are performed by using a transperitoneal approach to reach the uterus. The two major types of cesarean operations are classified by the location and direction of the uterine incision. The first are those incisions made in the upper segment of the uterus (Fig. 27.1). The vertical incision usually made in the anterior fundus is referred to as a classical incision. It is used primarily when it is difficult to deliver the infant through a low uterine segment incision. The second type is characterized by an incision made in the lower portion of the uterus after the bladder has been displaced downward (Fig. 27.2). The preferred and most frequently used is the low transverse incision. A vertical incision also may be made in this area, but it often involves the upper uterine segment unless the lower segment is quite elongated by labor.

Figure 27.2 Incisions in lower uterine segment. A: Low transverse incision. B: Low vertical incision. |

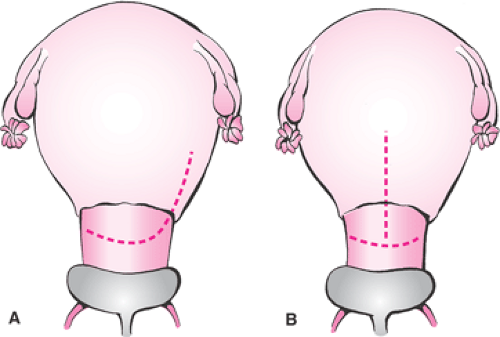

Variations are sometimes used because of unanticipated difficulty, but these incisions are best avoided by careful assessment and planning. (Fig. 27.3). A J-shaped incision is made when the obstetrician begins a transverse lower uterine segment incision and finds the lower uterine segment to be too narrow. It may not be realized that the incision is inadequate until delivery is attempted. The vertical extension from one end is necessary to avoid extension into the broad ligament. The T-shaped incision is made for similar reasons.

Anesthesia

The choice of anesthetic technique and agents is dictated by a number of factors. Patients with fetal distress, hemorrhage, shock, previous injury or surgery to the spine, or with skin infections of the lower back usually are not candidates for spinal or epidural anesthetic techniques. Conversely, a patient with active pulmonary disease such as pneumonia

and those who will be difficult to intubate are not good candidates for inhalation anesthesia. In most cases, the technique utilized depends primarily on such factors as urgency of delivery.

and those who will be difficult to intubate are not good candidates for inhalation anesthesia. In most cases, the technique utilized depends primarily on such factors as urgency of delivery.

Figure 27.3 Undesirable variations of uterine incisions. A: J-shaped incision. B: T-shaped incision. |

Maternal and fetal hemodynamics are markedly affected by maternal position. In the dorsal recumbent position, the gravid uterus compresses the inferior vena cava. Decreased venous return and maternal cardiac output result in hypotension and reduced uterine perfusion referred to as the inferior vena cava syndrome. The weight of the pregnant uterus also progressively compresses the aorta as the mean arterial pressure falls, thus reducing blood flow to the pelvis. Hypotension produced by regional anesthetic techniques compounds this problem. Devices attached to the operating table, inflatable wedges or towels placed under the patient, or tilting the table are used to displace the uterus to the patient’s left in preparation for cesarean. Rapid intravenous infusion of fluids immediately before the placing the regional anesthetic block also reduces the incidence of hypotension.

The status of the fetus worsens as the time of exposure to anesthesia lengthens. Progressive fetal depression is prevented by avoiding unnecessary delay from induction-to-delivery time. The abdomen should be fully prepped, draped, and ready for the incision before general anesthesia is induced. On the other hand, reckless surgical techniques for rapid delivery of the fetus are unwise. An induction-to-delivery time of 5 to 15 minutes is reasonable if maternal oxygenation, blood pressure, and displacement of the uterus are monitored and maintained.

Operative Procedure

Cesarean delivery requires the same preoperative care as for any major surgery and additional consideration for the status of the fetus. A patient who is dehydrated from prolonged labor needs correction with intravenous fluids. Because anemia is relatively common in pregnancy, a hemoglobin or hematocrit should be checked preoperatively. Blood that is typed and screened may need to be available for immediate transfusion in emergencies. Routine preparation of autologous or donor blood is not cost-effective for most cesarean patients because few patients are transfused. However, autologous blood can be prepared during the antepartum period if the patient is at high risk for hemorrhage, as with placenta previa or acreta. An indwelling catheter is routinely placed before beginning surgery since the bladder is in the operative field. Informed consent from the patient and her partner includes an explanation of the details of the operation, the risks involved, and the reason it is necessary. Written permission for the procedure, anesthetic, administration of blood, and possible hysterectomy if necessary is then signed by the patient.

With elective primary or repeat cesarean delivery, it is the obligation of the physician to first document evidence of fetal maturity, as outlined in Table 27.2. These criteria do not preclude the use of menstrual dating. If the criteria confirm gestational age assessment on the basis of menstrual dates in a patient with normal menstrual cycles and no immediately antecedent use of oral contraceptives, delivery can be scheduled at >39 weeks by menstrual dates. Ultrasound is useful to confirm menstrual dates. The gestational age should agree within 1 week by crown–rump measurement obtained at 6 to 11 weeks or within 10 days by the average of multiple measurements obtained at 12 to 20 weeks. When the fetal gestational age is uncertain, amniocentesis for amniotic fluid studies should by used to ensure fetal maturity. Awaiting the onset of spontaneous labor is another option.

TABLE 27.2 Fetal Maturity Assessment before Elective Repeat Cesarean Delivery | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Preparation

Preparation of the abdomen includes scrubbing the skin with soap and an antiseptic agent such as nonorganic iodide. The abdomen is then draped, leaving the area for the incision exposed.

Aspiration of the acidic contents of the stomach is a known risk when general anesthesia is used in pregnant women. The resulting pneumonitis is called Mendelson syndrome. Pretreatment with any of several medications reduces the risk of aspiration.

Prophylactic antibiotics are used to reduce the incidence of postpartum infection. The risk of postpartum endometritis is increased by duration of labor, prolonged rupture of the membranes, and number of cervical examinations. A single dose of a broad spectrum antibiotic, such as 1 gm of a cephalosporin, is recommended at delivery after the umbilical cord is clamped. With a clinically apparent intrapartum infection, therapeutic antibiotics started before surgery are continued into the postoperative period.

A pediatrician, neonatologist, or other physician should be available in the operating room if there is indication that the infant will need resuscitation.

Surgical Technique

The transverse Pfannenstiel and lower abdominal midline vertical are the two most commonly used skin incisions. Speed of entry through the low vertical incision facilitated by diastasis of the rectus muscles during pregnancy permits rapid access to the lower uterine segment in emergencies. This incision minimizes blood loss and allows extension for examination of the upper abdomen, if necessary. However, the transverse Pfannenstiel incision is used more frequently because of the cosmetic result preferred by most women. Moreover, entry through this incision is relatively rapid in the hands of an experienced surgeon, visualization of the pelvis is adequate, and there is less risk of subsequent herniation.

The abdomen is opened in layers, the abdominal cavity is briefly inspected, and the direction and degree of rotation of the uterus is quickly noted. Retractors placed in the abdominal incision are pulled laterally to expose the anterior surface of the uterus and the bladder covering the lower uterine segment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree