Cervical Cancer

Robert L. Giuntoli II

Robert E. Bristow

In the 1930s, cervical cancer was the number one cause of cancer-related deaths among women in the United States. With the advent of cytologic screening, there has been a 70% reduction in deaths from cervical cancer. The American Cancer Society has estimated that in the United States in 2007 there will be 11,150 new cases of invasive carcinoma of the cervix resulting in 3,670 deaths. The average age of diagnosis for cervical cancer is 52 years, and the distribution of cases is bimodal with peaks at 35 to 39 years and 60 to 64 years. Worldwide, cervical cancer continues to be a leading cause of death due to cancer among women, with approximately 500,000 cases estimated to have occurred in 2002. Lifetime risks for cervical cancer show significant geographic variation, ranging from 0.4% in Israel to 5.3% in Cali, Colombia.

Risk Factors

Screening

Cytologic evaluation of cells obtained from the cervix and vagina was first proposed by Papanicolaou and Traut in the 1940s as a method for detecting cervical cancer and its precursors. Cervical cytology has proved to be the most efficacious and cost-effective method for cancer screening. By increasing detection of preinvasive and early invasive disease, cervical cancer screening with the Pap smear has decreased both the incidence and mortality from cervical cancer in communities with active screening programs. A single negative Pap smear may decrease the risk for cervical cancer by 45%, and nine negative smears during a lifetime decrease the risk by as much as 99%. The introduction of liquid-based cervical cytology has resulted in improved sensitivity without loss of specificity. Additionally, human papillomavirus (HPV) testing can be performed on the remaining sample in order to better triage women with early cytologic changes.

Despite the recognized benefits of cytologic screening, substantial subgroups of women in the United States do not undergo appropriate screening. One half of women with newly diagnosed invasive cervical carcinoma have never had a Pap smear, and another 10% have not had a Pap smear in the 5 years preceding diagnosis. The absence of prior regular Pap smear screening is associated with a two- to sixfold increase in the risk of developing cervical cancer. Unscreened populations include older women, the uninsured, ethnic minorities, and women of lower socioeconomic status, particularly those in rural areas. Women over age 65 years should continue to be screened, as 25% of all cases of cervical cancer and 41% of deaths from the disease occur in women in this age group.

Race

Although the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States has declined significantly, the rates among blacks remain about twice as high as those among whites. The incidence is also approximately two times higher for Hispanic Americans and even higher for Native Americans, while most Asian American groups experience rates similar to whites. When socioeconomic differences are controlled for, the excess risk of cervical cancer among blacks is substantially reduced, from >70% to <30%. Racial differences are also apparent in survival, with 59% of blacks with cervical cancer surviving 5 years compared to 67% of whites with the disease.

Sexual and Reproductive Factors

First intercourse before 16 years of age is associated with a twofold increased risk of cervical cancer compared with that for women whose first intercourse occurred after age 20 years. Cervical cancer risk is also directly proportional to the number of lifetime sexual partners. Although difficult to separate epidemiologically, there is evidence to

indicate that both early age at first coitus and the number of lifetime sexual partners have independent effects on cervical cancer risk. Increasing parity also appears to be a separate risk factor for cervical cancer, even after controlling for socioeconomic and reproductive characteristics.

indicate that both early age at first coitus and the number of lifetime sexual partners have independent effects on cervical cancer risk. Increasing parity also appears to be a separate risk factor for cervical cancer, even after controlling for socioeconomic and reproductive characteristics.

Smoking

Cigarette smoking has emerged as an important etiologic factor in squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the cervix. The increased risk for smokers is approximately twofold, with the highest risk observed for long-term or high-intensity smokers. Proposed mechanisms include genotoxic or immunosuppressive effects of smoke-derived nicotine and cotinine, present in high levels in the cervical mucus of smokers.

Contraceptive Use

Numerous confounding factors—time interval since last cervical smear, sexual behavior, and role of the male partner, among others—complicate the interpretation of the data on oral contraceptive use and cervical cancer. After controlling for these and other variables, it appears that long-term oral contraceptive users (≥5 years) have about a twofold increased risk of cervical cancer compared with that of nonusers. Use of barrier methods, especially those that combine both mechanical and chemical protection, have been shown to lower the risk of cervical cancer, presumably because of reduced exposure to infectious agents.

Immunosuppression

Cell-mediated immunity appears to be a factor in the development of cervical cancer. Immunocompromised women (e.g., from renal transplantation or HIV infection) may not only be at higher risk for the disease but also demonstrate more rapid progression from preinvasive to invasive lesions and an accelerated course once invasive disease has been diagnosed. HIV-positive women with cervical cancer may have a higher recurrence risk and cancer-related death rate compared with HIV-negative control subjects.

Human Papillomavirus Infection

HPVs are members of the family Papovaviridae. They are nonenveloped virions with a double-stranded circular DNA genome of 7,800 to 7,900 base pairs contained in an icosahedral capsid. HPV infects epithelial cells of the skin and mucosal membranes. The HPV genome contains three regions. The upstream regulatory region (URR) controls production of viral proteins. The early region encodes for proteins E1, E2, E3, E4, E5, E6, and E7, which influence viral infection and replication. The late region encodes proteins L1 and L2, which are the major and minor capsid proteins, respectively. Differences in E6, E7, and L1 gene sequences of >10% constitute a distinct HPV type. Of the more than 100 types of HPV characterized, over 30 infect the anogenital tract.

Accumulated epidemiologic evidence has demonstrated HPV infection to be a necessary but insufficient factor in the development of invasive cervical cancer. Walboomers and associates found 99.7% of invasive cervical cancers to be positive by polymerase chain reaction for HPV DNA. HPV 16 and 18 account for approximately 67% of invasive cervical cancers.

Infection by HPV results in translation and transcription of the early proteins. The E6 and E7 open reading frames of the HPV genome are particularly important in the immortalization and transformation of infected cells. The protein products synthesized from the E6 and E7 open reading frames can bind to the gene products of the p53 and retinoblastoma (Rb) tumor suppressor genes, respectively. In condylomas and low-grade dysplasias, HPV DNA remains in an episomal (closed circular) form in which E6 and E7 transcription remains well regulated. Viral integration results in the overexpression of the E6 and E7 viral protein products with increased binding and inactivation of their respective tumor suppressor proteins. Removal of these inhibitory influences on cellular proliferation is thought to provide HPV-infected cells with a growth advantage, ultimately leading to neoplastic transformation. E6 and E7 are consistently expressed in HPV-associated anogenital malignancies.

HPV types are divided into three groups based on their association with neoplastic and malignant processes. Low oncogenic risk–type viruses include types 6, 11, 42, 43, and 44 and are associated with condyloma acuminatum and some cases of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions but rarely with invasive cancer. High oncogenic risk–type viruses include types 16, 18, 31, 45, and 56 and are commonly detected in women with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HGSIL) and invasive cancer. HPV types 33, 35, 39, 51, and 52 can be considered as being of intermediate oncogenic risk, as they are occasionally associated with HGSIL and invasive carcinomas. The oncogenic risk of the HPV types appears to be related to the binding affinity of their E6 and E7 proteins to p53 and Rb respectively. E6 and E7 proteins from high-risk HPV bind with high affinity to p53 and Rb, respectively, whereas low-risk HPV E6 and E7 proteins bind with very low affinity.

HPV is the most common sexually transmitted disease. An estimated 75% to 80% of sexually active women will test positive at some point for HPV DNA. HPV infections are most common at the onset of sexual activity, with the majority of infections being transient. Serial testing typically demonstrates clearing of the virus. Persistent infection occurs in the minority of women, and these individuals are at highest risk for precancerous and invasive lesions. The incidence of dysplasia is approximately ten times lower than the incidence of HPV infection and reflects the transient nature of the majority of HPV infections.

Clinical Features

Presenting Symptoms

The most common symptom of cervical cancer is abnormal vaginal bleeding or discharge. Abnormal bleeding may take the form of postcoital spotting, intermenstrual bleeding, menorrhagia, or postmenopausal spotting. Chronic bleeding can be associated with fatigue or other symptoms related to anemia. Serosanguineous or yellowish vaginal discharge, frequently associated with a foul odor, may accompany an advanced or necrotic carcinoma. Pelvic pain may result from locally advanced disease or tumor necrosis. Tumor extension to the pelvic side wall may cause sciatic pain or back pain associated with urinary tract obstruction and hydronephrosis. Metastatic tumor to the iliac and paraaortic lymph nodes can extend into the lumbosacral nerve roots and present as lumbosacral back pain. Urinary or rectal symptoms (e.g., hematuria, hematochezia, fistulas) can be associated with bladder or rectal invasion by advanced-stage cervical carcinoma.

Physical Findings

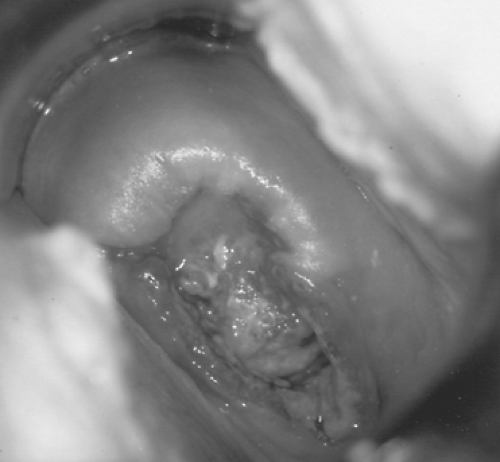

Invasive carcinoma of the cervix displays a wide range of gross appearances. Early lesions may be focally indurated or ulcerated or present as a slightly elevated and granular area that bleeds readily on contact (Fig. 58.1). More advanced tumors have several types of gross appearance: exophytic, endophytic, or infiltrative. Exophytic tumors characteristically have a friable polypoid or papillary appearance. Endophytic tumors are usually ulcerated or nodular but may be clinically inapparent if located high within the endocervical canal. Such tumors frequently invade deep into the cervical stroma to produce an enlarged, hard, barrel-shaped cervix that may only be appreciated on rectovaginal pelvic examination. The infiltrative pattern of tumor growth may produce surrounding tissue necrosis and erosion of normal anatomic landmarks.

Spread of Disease

Parametrial Extension

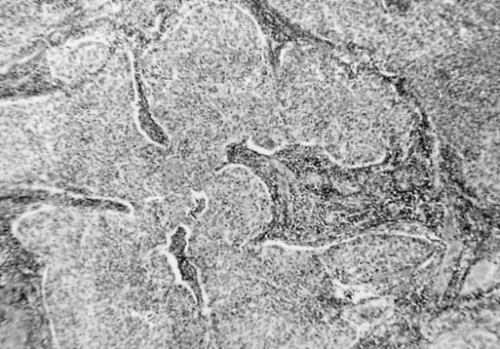

Cervical cancer generally follows an orderly pattern of disease progression. Initially, tumor cells usually spread through parametrial lymphatic vessels, expanding and replacing parametrial lymph nodes (Fig. 58.2). These individual tumor masses enlarge and become confluent, eventually replacing the normal parametrial tissue. Less commonly, the central tumor mass reaches the pelvic sidewall by direct contiguous extension through the cardinal (Mackenrodt) ligament. Significant involvement of the medial portion of this ligament may result in ureteral obstruction and hydronephrosis.

Lymph Node Involvement

Pelvic lymph nodes are usually the first site of embolic lymphatic spread of cervical cancer. The lymph node groups most commonly involved are the obturator, external iliac, and hypogastric (Fig. 58.2). Isolated, positive common iliac nodes have been reported and these nodes should be included in a pelvic lymphadenectomy. The inferior gluteal and sacral lymph nodes are less frequently involved. Secondary nodal involvement (i.e., paraaortic) seldom occurs in the absence of pelvic nodal disease. Rarely, retrograde lymphatic embolization may occur to the inguinal lymph nodes. Patients with locally advanced pelvic disease may have detectable metastatic spread to the scalene nodes. Consequently, careful clinical assessment of the groin and supraclavicular fossa areas should be included as part of the physical examination.

Vaginal Extension

When the primary tumor has extended beyond the confines of the cervix, the upper vagina is frequently involved (50% of cases). Anterior extension through the vesicovaginal septum is most common, often obliterating the dissection plane between the bladder and underlying cervical tumor, making surgical therapy difficult or impossible. Posteriorly, a deep peritoneal cul-de-sac (pouch of Douglas) can represent an anatomic barrier to direct tumor spread from the cervix and vagina to the rectum.

Bladder and Rectal Involvement

In the absence of lateral parametrial disease, anterior and posterior spread of cervical cancer to the bladder and rectum is uncommon. Approximately 20% of patients with tumor extending to the pelvic sidewall will have biopsy-proven bladder invasion.

Endometrial Involvement

The endometrium is involved in 2% to 10% of cervical cancer cases treated with surgery, although the overall incidence (including nonsurgical cases) is unknown. Although endometrial extension does not alter a patient’s stage of disease, it has been associated with decreased survival and a higher incidence of distant metastases.

Ovarian Metastasis

Rarely, ovarian involvement with cervical cancer occurs through the lymphatic connections between the uterus and adnexal structures. In patients undergoing surgical treatment for early-stage disease, ovarian metastasis is present in <1% of SCCs and slightly >1% of adenocarcinomas. The true incidence of ovarian involvement with advanced-stage tumors is unknown, as pathologic evaluation of the adnexae is not commonly performed in such cases.

Hematogenous Spread

Hematogenous spread of cervical cancer is uncommon, particularly at the time of initial diagnosis. However, when blood-borne metastases do occur, the lung, liver, and bone are the sites most frequently involved.

Diagnosis and Staging

Diagnosis and Evaluation of Disease Extent

Pathologic documentation of invasive disease should always be obtained prior to initiating therapy for cervical cancer. Cervical cancer is one of the two gynecologic malignancies (vaginal cancer being the other) that still uses a clinically based staging system, which facilitates comparison of results between institutions irrespective of the availability of diagnostic technological resources. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system used for cervical carcinoma is based on clinical evaluation (visual inspection, palpation, colposcopy); radiographic examination of the chest, kidneys, and skeleton; and endocervical curettage and biopsies (conization or incisional biopsies). Staging procedures allowed by FIGO convention are shown in Table 58.1. Lymphangiograms, arteriograms, computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and laparoscopy or laparotomy should not be used for clinical staging. However, information from such additional studies and procedures may be used to modify the treatment approach.

In 1995, FIGO revised the clinical staging system of cervical carcinoma (Table 58.2). Stage I disease includes those neoplasms that are clinically confined to the cervix. In the current staging classification, stage IA tumors are those that are diagnosed by microscopic evaluation of a conization specimen (microinvasive carcinoma). Stage IA1 is defined as a tumor with stromal invasion no >3 mm in depth

beneath the basement membrane and no >7 mm wide. Stage IA2 tumors have stromal invasion >3 mm but no >5 mm deep and are no >7 mm wide. This division in the definition of microinvasive disease reflects data indicating that patients with <3 mm of invasion are at very low risk of metastatic disease and may be treated more conservatively. All grossly visible lesions should technically be classified as stage IB. The 1995 staging system divides stage IB lesions into stage IB1 (no >4 cm in maximal diameter) and stage IB2 (>4 cm in maximal diameter), reflecting the prognostic importance of tumor volume for macroscopic lesions limited to the cervix.

beneath the basement membrane and no >7 mm wide. Stage IA2 tumors have stromal invasion >3 mm but no >5 mm deep and are no >7 mm wide. This division in the definition of microinvasive disease reflects data indicating that patients with <3 mm of invasion are at very low risk of metastatic disease and may be treated more conservatively. All grossly visible lesions should technically be classified as stage IB. The 1995 staging system divides stage IB lesions into stage IB1 (no >4 cm in maximal diameter) and stage IB2 (>4 cm in maximal diameter), reflecting the prognostic importance of tumor volume for macroscopic lesions limited to the cervix.

TABLE 58.1 Staging Procedures for Cervical Cancer | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

TABLE 58.2 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Staging of Cervical Carcinoma | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Examination under anesthesia is recommended for accurate staging. It is important to palpate the entire vagina to determine whether disease is limited to the cervix (IB), extends to the upper two thirds of the vagina (IIA), or also involves the lower third of the vagina (IIIA) (Fig. 58.3). Tumor extension into the parametrial tissue (IIB) or to the pelvic sidewall (IIIB) is best appreciated on rectovaginal examination. It is impossible at clinical examination to decide whether a smooth and indurated parametrium is truly cancerous or only inflammatory, and the case should be considered stage III only if the parametrium is nodular on the pelvic wall or if the growth itself extends to the pelvic wall. Biopsy-proven invasion of bladder or rectal mucosa by cystoscopy or proctoscopy is required for a diagnosis of stage IVA disease. In the United States, the distribution of patients by clinical stage is stage I, 38%; stage II, 32%; stage III, 26%; and stage IV, 4%.

When there is doubt concerning which stage a tumor should be assigned, the earlier stage is mandatory. Once a clinical stage has been determined and treatment initiated, subsequent findings on either extended clinical staging (CT, MRI, etc.) or surgical exploration should not alter the assigned stage. Assignment of a more advanced stage during treatment will result in an apparent but deceptive improvement in the results of treatment for earlier stage disease.

Surgical or Radiographic Staging

The current FIGO staging classification for cervical cancer is based on pretreatment clinical findings. Only the subclassification of stage I (IA1, IA2) requires pathologic assessment. Although nonapproved studies or procedures do not change FIGO clinical staging, the results can impact prognosis or treatment. Discrepancies between clinical staging and surgicopathologic findings range from 17.3% to 38.5% in patients with clinical stage I disease to 42.9% to 89.5% in patients with stage III disease. This has led some authors to emphasize surgical staging of cervical carcinoma to identify occult tumor spread and determine the presence

of extrapelvic disease so that adjunctive or extended-field radiation therapy may be offered. Transperitoneal surgical staging procedures (e.g., laparotomy), when followed by abdominopelvic irradiation, are associated with appreciable complications, particularly enteric morbidity. The extraperitoneal surgical approach can be performed through a paraumbilical or paramedian incision or laparoscopically and allows accurate assessment of pelvic and paraaortic nodal status. Using this approach, an incision in the peritoneum is avoided and adhesion formation is minimized. It is associated with few complications and does not delay institution of radiation therapy. Others have advocated imaging studies to evaluate lymphatic involvement. Combined positron emission tomography–CT has been associated with a sensitivity of 73% in identifying stage I cervical cancer patients with positive lymph nodes. This combined modality may also be utilized in the restaging of patients with a suspected cervical cancer recurrence.

of extrapelvic disease so that adjunctive or extended-field radiation therapy may be offered. Transperitoneal surgical staging procedures (e.g., laparotomy), when followed by abdominopelvic irradiation, are associated with appreciable complications, particularly enteric morbidity. The extraperitoneal surgical approach can be performed through a paraumbilical or paramedian incision or laparoscopically and allows accurate assessment of pelvic and paraaortic nodal status. Using this approach, an incision in the peritoneum is avoided and adhesion formation is minimized. It is associated with few complications and does not delay institution of radiation therapy. Others have advocated imaging studies to evaluate lymphatic involvement. Combined positron emission tomography–CT has been associated with a sensitivity of 73% in identifying stage I cervical cancer patients with positive lymph nodes. This combined modality may also be utilized in the restaging of patients with a suspected cervical cancer recurrence.

Prognostic Variables

Tumor Characteristics

Clinical stage of disease at the time of presentation is the most important determinant of subsequent survival, regardless of treatment modality. Five-year survival declines as FIGO stage at diagnosis increases: stage IA, 97%; stage IB, 70% to 85%; stage II, 60% to 70%; stage III, 30% to 45%; stage IV, 12% to 18%. Prognostic variables directly related to surgicopathologic tumor characteristics and their effect on survival were compiled by Kosary for the National Cancer Institutes Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program for the period of 1973 through 1987. This study included 17,119 cases of invasive cervical cancer and found that FIGO stage, tumor histology, histologic grade, and lymph node status are all independent prognostic variables relating to survival.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree