Adolescence is a journey through physiologic, cognitive, and psychologic stages, an integral aspect of which is the development of the adolescent as a sexual being. A successful journey through adolescence will result in the successful development of the individual’s sexuality and subsequently largely determine his or her nature as an adult.

Western society places unreasonable pressure on adolescents, which is reflected in the difficulty they have with finding their roles as sexual beings. Television and take-away videos provide easy and non-stop access to distorted sexual attitudes and activity. Many youth have faced the horror of child sexual and verbal abuse, and all are affected by the quality (good or bad) of the sexuality education we, as adult society, give them. The comprehension of adolescent sexuality is not easy, even for health care workers. It is a physioanatomic, biologic, psychosocial, moral, and ethical phenomenon, existing as a continuum (instead of an endpoint) within a community that is grappling with its own constantly changing stressors and varying standards of sexuality.

The sexuality issues of the adolescent begin during childhood. Those youth who lived with a childhood of abuse, neglect, parental divorce, family chaos, or other negative experiences have less than the ideal template for the development of their adolescent sexuality. Parental attitudes toward clinically normal sexual development are vitally important to the overall development of the emerging individual.

Regardless of one’s chosen scope of chiropractic practice, an understanding of adolescent sexuality is vital for the establishment of an adequate professional relationship with the adolescent as a patient. Should your scope of practice be broad enough to include the room to work with issues of adolescent sexuality, then further study and membership of appropriate professional bodies is essential. On a day-to-day basis, the chiropractor needs to understand that the adolescent patient is neither a child nor an adult; therefore, management strategies that are otherwise effective in one’s practice may singularly fail for the adolescent patient. Furthermore, adolescence is a journey in itself and not just a whistle-stop one passes through while progressing from the cradle to the grave. As such, it has a myriad of nuances that interact to varying degrees at varying times. Fortunately for the practitioner, however, the journey through adolescence largely can be considered to occur in three stages.

Stages of Adolescence

Adolescence can be viewed in terms of early, mid, and late, each with its own characteristics and problems.

Traditionally, the early stage is ages 10 to 14 years, the middle stage is ages 14 to 18, and the late stage is ages 18 to 21 or 22, with a crossover phase into adulthood and growth completion between the ages of 21 and 24 years. The stages are only guidelines, however, and it is important to remember that all patients have the right to present in the stage of development in which they find themselves at the time. On the basis of there being some sort of mean range within which developmental landmarks generally occur, it can be said that some teenagers have precocious development whereas others are delayed, but, remember, the term “delayed” is only a label and one must be cautious when thinking about whether or not to apply it.

Each stage has its own characteristics for growth, cognition, psychosocial self, family relationships, peer group relationships, sexuality, and chronological age range. They are listed in

Table 21.1. There are further stages that can add to one’s concept of adolescence, such as those of Kolberg, Freud, Sears, Havighurst, Kinsey, Lidz, and Gillian, Miller, and Chodorow; these can be explored at one’s discretion and leisure.

Early Adolescence The chronological age range of early adolescence is 10 to 14 years. Sexual function will occur before biologic maturation, and generally the concepts of sexuality are initiated in the youth’s mind by the events of puberty. The body increases in height and weight as growth accelerates, and the secondary sexual characteristics appear. The time lapse between childhood and adulthood stages is from 2 to 4 or perhaps 5 years.

Growth is initiated by the hypothalamus through stimulation of the anterior pituitary and is controlled by various hormones. The amount of sex steroids produced by the body slowly increases from approximately age 6 years. Puberty commences with the triggering of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Gn-RH). It is believed that this system is controlled by a highly sensitive negative feedback system that inhibits the synthesis of effective levels of Gn-RH earlier in life. As age increases, it is thought that the sensitivity of the negative feedback mechanism decreases and the hormones reach endocrinologically effective levels. The critical weight hypothesis of Frisch-Revelle (

38) suggests that the decreasing sensitivity is related to a statistically significant correlation between menarche and the achievement of a critical body weight of 47.8 kg. The hypothesis has been modified to relate more to a ratio between body fat, total body water, and lean mass (

22) and remains a useful clinical indicator.

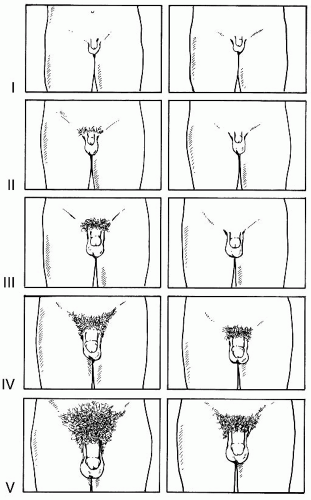

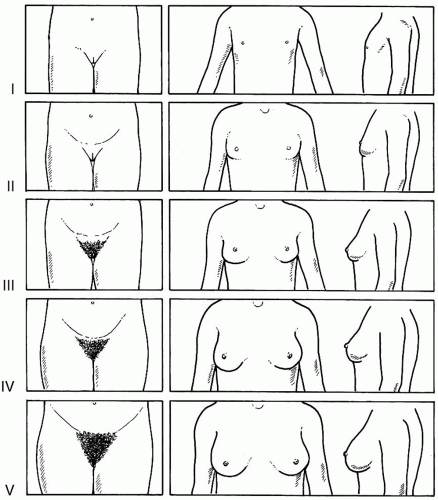

The biologic changes are categorized by Tanner, with genital maturity ratings that range from 1 to 5 (

Tables 21.2 and

21.3). They apply to the secondary sexual characteristics of the man and woman, and allow

a “staging” of the individual’s biologic development (

Figs. 21-1 and

21-2). Although not used during day-to-day chiropractic practice, the stages do form an important part of the patient record for complaints such as delayed menarche (primary amenorrhea) or short stature. Because evaluations of Tanner staging should only be performed by a chiropractor in the presence of a chaperone of the same sex as the patient or in the presence of the patient’s parent or guardian, it is often easier to use the “self-reporting” method, in which the patient is asked to identify which of a series of Tanner drawings most closely resembles himself or herself. This method has been found to be reasonably reliable (

39), has been recommended by other chiropractic authors (

40), and is much more practical for use outside the office, for example, when conducting preparticipation examinations for a sporting organization.

Adolescent growth, these times of tremendous biological change, occurs at different chronological ages in men and women. Female puberty is heralded by thelarche (the budding of the breast) at about age 11 (range, 8 to 15 years of age), which is Tanner stage 2. Puberty starts 1.5 to 2 years later in boys and takes nearly twice as long to complete. Menarche occurs approximately

2.5 years after the onset of puberty, or during stage 4, at which time the girl has attained 90% to 95% of her adult height.

In boys, the first observable change is testicular enlargement, beginning at 11.6 years of age (range, 10 to 14.8 years of age). The male growth spurt usually begins at Tanner stage 3, peaks during stage 4, and is all but complete by stage 5; however, some boys will continue to grow up to 2 cm more in height over the ensuing 5 years. Another characteristic of importance to manual practitioners is the period of male puberty, which sees rapid muscle growth, the “strength spurt,” at the end of stage 4.

Linear growth follows these early changes in sexual characteristics, with an initial increase in the length of the long bones, which causes a rise in the body’s center of gravity. This is followed by growth of the spine, which reestablishes equilibrium in the ratio of upper to lower body segments. This is the “growth spurt” of Tanner, or the period of peak height velocity, which in

girls commonly starts during Tanner stage 2, reaches a peak midway between stages 3 and 4, and ends at stage 5. In boys, the peak height velocity occurs later, during genital stage 4. During the growth spurt the “average” girl will grow at a peak velocity of 8 cm per year and the “average” boy at 10 cm per year, adding as much as 20 cm to his height. Similar dimensional increases occur in every body system apart from the lymphatic, in which total tissue volume decreases.

Because youth enter puberty at such varying times, any comparison between individuals is best made on the basis of Tanner staging. We therefore have chronological age, Tanner stage, cognitive level, and psychosocial development as aspects to consider when talking about adolescents. It is essential to understand these relationships with their standard deviations to correctly evaluate normal and problematic growth states such as delayed puberty, short stature, or delayed menarche.

Piaget has described the cognitive stages of development, which reach the concrete operational stage between the ages of 7 and 11 years. The adolescent generally will be making the entry into adolescence and puberty from the concrete stage; however, the stage may last until well into adolescence. Concrete thought is limited to considering things and specific situations in existential terms, with no ability to extract general principles from one experience and apply them to a wholly new experience.

A feature of the concrete operational stage of interest to chiropractors is the monosyllabic nature of responses to questioning. There should be some ability to understand the concepts of symmetric relationships and serializations, although this ability can be expected to vary greatly between adolescents. Concrete thinkers may well be interested in the physical aspects of their bodies but may be unable to express themselves clearly and in detail. Questionnaires can be useful at this stage to identify the key points of a health history. Teaching aids are also of great benefit to extend the patient’s knowledge and understanding. The thinking of the concrete adolescent is very much in the present, with a resultant difficulty to think in futuristic terms.

The implication for clinical practice is that therapeutic recommendations need to be accompanied by evidence of an immediate benefit. For example, “sex is OK” because “it feels good right now”; the risk of pregnancy and delivery is 9 months in the future and is not comprehensible. The future cannot be appreciated except as a direct projection of clearly visible, current operations. The difficulty of counseling around inappropriate behavior is compounded by the concept of “magical thinking,” in which the adolescent feels he or she is untouchable. Accordingly, they do not perceive the risks that attend risky behavior because they feel they are “special” and essentially “untouchable” by any future danger. This magical thinking can extend well into late adolescence (to include about 30% of late adolescents) and even adulthood, as evidenced by the number of adults who take drugs, smoke, drive irresponsibly, and abuse alcohol. Generally the adolescent progresses to formal operational thinking by mid adolescence.

The psychosocial self of adolescence is dominated by the rapid physiologic growth changes of puberty with its various aches and musculoskeletal pains. These can lead to a hypochondriacal phase until the changes become more familiar. The family relationship lessens, with a commensurate strengthening of the peer group relationship. As the teenager starts to move away from the parent he or she forms stronger friendships and bonds with peers, the new source of one’s sense of self-worth. This is a time of strong comparison with one’s peers, and friendships tend to be of the same sex, with some possible homosexual experimentation.

Mid Adolescence The chronological age range is 14 to 18 years and the formal operational thinking patterns are now developing. This abstract thinking permits the conceptualization of possibilities beyond past and present experiences. The emerging phase is attended by a preoccupation with fantasy and ideas, which develop into a strong ability to comprehend logic that can be used in profound arguments to counter parental direction. Any guidance given by health care workers needs to be extremely clearly presented with fully explained rules or recommendations, especially with preventive health strategies.

These youth are balancing the newfound power of formal operational thinking with the emergence of a need for independence. They lack the level of experience needed to avoid errors in judgment, especially when “magical thinking” remains, but they can achieve independence and make career and lifestyle choices while their personal value system emerges. Formal thought may not be applied at all times; some simple situations may not need it, whereas some other occasions may overwhelm the person, who then reverts to irrational thought.

The psychosocial self shows a stronger reliance on peers with an acquisition of greater independence and emancipation from the parents. The kind of youth with which one associates reflects one’s sense of self worth. Individuals with undesirable peer group associations, such as those with drug-taking habits, seem more prone to depression at this stage. Though self-confident youth generally associate with similarly self-confident youth, parents and health care workers should be aware of the futility of attempting to force certain relationships onto the adolescent.

Heterosexual experimentation is inevitable and parental attitudes become critical. A youth who is

rebelling against authority may demonstrate such rebellion sexually. Coital activity is common, with the resultant high rates of pregnancy, abortion, and sexually transmitted diseases, which in turn can further complicate parent-adolescent relationships. The developing emancipation and heterosexual experimentation strengthens cognitive abilities. Various adults may serve as role models (good or bad), and youth often turn to other adults for counseling in addition to or instead of their parents. It is at this time that the chiropractor’s influence is significant, especially because questions of a moral, ethical, and religious nature are often asked. The difficulties experienced vary greatly. Some adolescents may pass through this stage with little upheaval, whereas others may turn to experimentation with drugs and may exhibit transient school dysfunction, moodiness, and irritability. This is a relevant time to consider the appropriate type of counseling should it be indicated.

Late Adolescence The chronological age range is from 18 years to the end of skeletal growth, between 21 and 24 years. By the 25th birthday, all secondary ossification centers should be fused and growth should be complete. The adolescent will exhibit sound formal operational thinking with strong cognitive skills and can be considered an adult, with both the independence and experience needed to reduce errors in judgment. There is some final physiologic fine tuning, such as regulation of menstruation and male muscular development. The male growth spurt should be all but complete by Tanner stage 5; however, it must be appreciated that some men will continue to grow up to 2 cm more during the ensuing 5 years. Another characteristic of importance to chiropractors is the period in men that sees rapid muscle growth, the “strength spurt,” at the end of stage 4.

The psychosocial self will by now be resolving the issues of emancipation and the youth-parent relationship, which should be more adult-adult in nature and more comfortable. Ideally, a young adult emerges, a person who likes him or her self as a man or woman and has come to grips with important issues of human sexuality. The body image will be secure and the gender role established, two keys to potential success during late adolescence and adulthood. Any necessary corrections to the musculoskeletal system from the chiropractor’s viewpoint will have been made and the entry into adulthood should be based on a firm, pain-free, fully functional structural foundation. Those youth who still experience difficulty in this stage may also experience considerable anxiety or depression, and care must be taken to distinguish between genuine physical need for adjustive treatment and a perceived demand based on the patient remaining in a “comfort zone.” The rest of this transitional period involves the acquisition of adult lifestyles and habits, and one or several of a variety of sexual orientations will be adopted. This is also the time for establishment of vocational skills and of training to meet the complexities of modern society.