Breech, Other Malpresentations, and Umbilical Cord Complications

Timothy E. Klatt

Dwight P. Cruikshank

Breech Presentation

Breech presentation, the most common obstetric malpresentation, complicates approximately 4% of deliveries.

Definitions

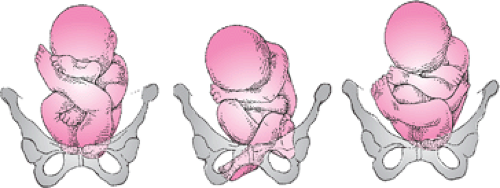

Breech presentation is a polar alignment of the fetus in which the fetal buttocks present at the maternal pelvic inlet. Three types are recognized: frank, incomplete, and complete. In frank breech presentation, the fetal hips are flexed and the knees extended so that the thighs are apposed to the abdomen and the lower legs to the chest (Fig. 22.1). The buttocks are the most dependent part of the fetus. Frank breech presentation accounts for 60% to 65% of breech presentations; it is more common at term. In incomplete breech presentation, the fetus has one or both hips incompletely flexed so that some part of the fetal lower extremity, rather than the buttocks, is the most dependent part (hence the terms single footling or double footling). This presentation accounts for 25% to 35% of breech presentations and is more common among premature fetuses. Complete breech presentation is the least common type, accounting for about 5% of breech presentations. In this situation, the fetal hips and knees are both flexed so that the thighs are apposed to the abdomen and the legs lie on the thighs. A significant proportion of these fetuses convert to incomplete breech presentations if allowed to labor. The position of the breech fetus is described with the fetal sacrum as the reference point; thus, it is right sacrum anterior, left sacrum posterior, left sacrum transverse, and so forth.

A spontaneous breech delivery is one in which the entire infant delivers vaginally without manual aid. In the unusual circumstance of a vaginal delivery of a singleton breech, the recommended form is the assisted breech delivery, also known as partial breech extraction. In this delivery, the fetus is allowed to deliver by the forces of uterine contractions and maternal bearing-down efforts until the fetal umbilicus has passed over the mother’s perineum. After this, delivery of the legs, trunk, and arms are assisted manually; the head may be delivered manually or with forceps. A complete breech extraction, in which manual assistance is applied by traction in the groins or on the lower extremities before delivery of the buttocks, is contraindicated in singleton breech presentations.

Incidence

The incidence of breech presentation is closely associated with birth weight. Breech presentation accounts for 4% of births overall but occurs in 15% of deliveries of low–birth-weight (<2,500 g) infants. Furthermore, the smaller the

infant, the higher the incidence of breech presentation, rising to 30% among infants weighing 1,000 to 1,499 g and to 40% among those weighing <1,000 g. Viewed from another perspective, the association between breech presentation and low birth weight is even more striking. Only 70% of infants who present as breeches weigh >2,500 g; 30% weigh <2,500 g (compared with 5% to 6% of infants who are in vertex presentation), and 12% are of very low birth weight, weighing <1,500 g.

infant, the higher the incidence of breech presentation, rising to 30% among infants weighing 1,000 to 1,499 g and to 40% among those weighing <1,000 g. Viewed from another perspective, the association between breech presentation and low birth weight is even more striking. Only 70% of infants who present as breeches weigh >2,500 g; 30% weigh <2,500 g (compared with 5% to 6% of infants who are in vertex presentation), and 12% are of very low birth weight, weighing <1,500 g.

Cause

Factors that predispose to breech presentation are listed in Table 22.1. The importance of fetal anomalies cannot be overemphasized (Table 22.2). Malformations of the central nervous system complicate 1.5% to 2.0% of breech births: the incidence of hydrocephalus is tenfold greater, and that of anencephaly twofold to fivefold greater, than it is among infants presenting as vertex. Up to 1% of infants in breech presentation have a significant chromosomal abnormality: 1 in 200 has Down syndrome, and the incidence of other autosomal trisomies is increased as well. Of those infants presenting as breeches, the incidence of major congenital anomalies is 17% among premature infants, 9% among term infants, and 50% among term infants who die in the perinatal period. It is prudent to keep these numbers in mind when deciding on a method of delivery for a fetus in breech presentation and to discuss the risk–benefit ratio with the parents.

TABLE 22.1 Factors Predisposing to Breech Presentation | |

|---|---|

|

For many years, an association between cerebral palsy and breech presentation (although not vaginal breech delivery) has been assumed. As it becomes apparent that most fetal insults leading to cerebral palsy occur before term, it appears that cerebral palsy is another cause of breech presentation. In fact, among term infants, the risk of cerebral palsy is not related to presentation after correcting for intrauterine fetal growth restriction. In >50% of cases, no causative factor for breech presentation can be identified.

Diagnosis

On abdominal examination, Leopold’s first maneuver will identify the fetal head in the fundus. The third maneuver reveals the softer breech over the pelvic inlet. It is useful to remember that the head narrows down to the neck before attaching to the body, whereas there is no such tapering between the buttocks and body. Auscultation of fetal heart tones usually reveals them to be most easily detected in the upper quadrants of the uterus when the fetus is in breech presentation.

The diagnosis often is made by vaginal examination. In frank or complete breech presentation, the anal orifice may be identified, with the bony prominences of the ischial tuberosities directly lateral to it. Face presentation may be difficult to distinguish from frank breech presentation on

digital examination, with the fetal mouth being mistaken for the anus. It is helpful to remember that the mouth is surrounded by bone, whereas the anus is not. In incomplete breech presentations, palpation of the feet on vaginal examination is diagnostic. During labor, any presentation that is not clearly vertex by vaginal examination should be confirmed by an intrapartum ultrasound.

digital examination, with the fetal mouth being mistaken for the anus. It is helpful to remember that the mouth is surrounded by bone, whereas the anus is not. In incomplete breech presentations, palpation of the feet on vaginal examination is diagnostic. During labor, any presentation that is not clearly vertex by vaginal examination should be confirmed by an intrapartum ultrasound.

TABLE 22.2 Congenital Malformations among Term Infants in Breech Presentation | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Perinatal Mortality

Perinatal mortality is higher in breech presentation than in vertex, being fourfold greater among term infants and twofold to threefold greater among premature infants. Much of this excess mortality is not currently preventable; 64% of deaths among term infants in breech presentation are due to malformations or infection. Among premature infants, malformations, infection, maternal disease, and intrauterine death before labor account for 56% of perinatal mortality, and complications of prematurity unrelated to the method of delivery account for another 11%. Thus, only about one third of perinatal deaths among breech infants are due to potentially preventable factors. These basically fall into two categories: trauma and asphyxia.

Trauma to the head is a significant risk in both term and premature infants who present as a breech, regardless of the route of delivery. Unlike the situation in vertex presentation, in which the fetal head is in the maternal pelvis for hours or days during which molding can occur, the after-coming head of the breech fetus must come through the pelvis as is—there is no time for molding. Thus, minor variations in maternal pelvic architecture, which would be insignificant in vertex presentation, may become major risks for the after-coming head. This problem is compounded for the infant at <32 weeks gestation, in whom the head is the largest part. In these circumstances, the fetal body may deliver through an incompletely dilated cervix, which then entraps the head. Performance of a cesarean either before or during labor does not ensure an atraumatic delivery of the head. An inadequate uterine incision or suboptimal uterine relaxation may still result in head entrapment, leading to significant injury to the infant.

When extracting a breech presentation, damage to fetal muscles, soft tissue, and viscera may occur with delivery if the fetus is grasped in places other than its bony pelvis. Likewise, delivery may be associated with nerve injury if the arms are not delivered properly, especially if there are nuchal arms. Finally, trauma to the cervical spinal cord may occur with delivery of a breech fetus with hyperextension of the neck.

Asphyxia may be caused by prolapse of the umbilical cord past the body, as the head will compress the cord against the cervix and pelvic soft tissues. The incidence of cord prolapse in term fetuses in frank breech presentation is 0.4%. In complete breech presentation, the incidence is 5% to 6%, and with incomplete breech presentation, the incidence may be as high as 10%. Cord prolapse in incomplete breech presentation, although an indication for prompt cesarean delivery, often is not the devastating event that it is in vertex or frank breech presentation. Because the cord is prolapsed between the fetal legs, it often is not markedly compressed during subsequent uterine contractions. Not all asphyxia among fetuses in breech presentation is caused by overt cord prolapse. Abnormalities of the fetal heart rate pattern during labor are four to eight times more common in fetuses in breech presentation than in fetuses presenting vertex. An unknown percentage of this undoubtedly is due to occult cord prolapse and other forms of cord compression.

Antepartum Management

Breech presentation diagnosed before 32 weeks gestation should be managed expectantly. Recently, it has been confirmed that a significant percentage of preterm fetuses in abnormal presentations (breech, transverse and oblique) spontaneously convert to vertex presentation as the gestation approaches term (Table 22.3). Breech presentation that persists into the late third trimester should be evaluated by an ultrasound examination for congenital anomalies. When a breech presentation persists beyond 32 weeks gestation, some obstetricians have recommended attempts at converting the presentation to vertex by external cephalic version (ECV). Ranney reported his experience with 860 patients managed by external version. Attempts were made to turn the fetus to vertex whenever breech presentation was found in the third trimester, and some patients had repeated versions performed. Ranney was able to lower the incidence of breech presentation at term to 0.6%, about one sixth the expected incidence, and encountered no fetal trauma or death and, specifically, no increase in the incidence of placental abruptions.

The report by Kasule and coworkers was less optimistic. All patients with fetuses in breech presentation after 30 weeks gestation were prospectively randomized to either

an external version group (310 patients) or a control group (330 patients). The subjects in the external version group had the procedure performed between 33 and 36 weeks gestation. If the first attempt failed, or if the fetus reverted to breech presentation, the procedure was repeated up to three times in subsequent weekly visits. No attempts at external version were made after 36 weeks gestation. Although their immediate success rate was 80%, 46% of fetuses spontaneously reverted to breech presentation. There were three perinatal deaths attributed to the procedure: two from abruptio placentae and one from premature labor and delivery. Most important, the incidence of breech presentation at delivery was 52% in the external version group and 51% in the control group, with 49% of fetuses in the control group converting to vertex presentation spontaneously before delivery. The authors surmised that many, if not all, of their successful external versions may have been in patients whose fetuses would have converted spontaneously had nothing been done. This hypothesis, coupled with the three perinatal deaths, led them to conclude that “there is no place for external cephalic version before 36 weeks gestation.”

an external version group (310 patients) or a control group (330 patients). The subjects in the external version group had the procedure performed between 33 and 36 weeks gestation. If the first attempt failed, or if the fetus reverted to breech presentation, the procedure was repeated up to three times in subsequent weekly visits. No attempts at external version were made after 36 weeks gestation. Although their immediate success rate was 80%, 46% of fetuses spontaneously reverted to breech presentation. There were three perinatal deaths attributed to the procedure: two from abruptio placentae and one from premature labor and delivery. Most important, the incidence of breech presentation at delivery was 52% in the external version group and 51% in the control group, with 49% of fetuses in the control group converting to vertex presentation spontaneously before delivery. The authors surmised that many, if not all, of their successful external versions may have been in patients whose fetuses would have converted spontaneously had nothing been done. This hypothesis, coupled with the three perinatal deaths, led them to conclude that “there is no place for external cephalic version before 36 weeks gestation.”

TABLE 22.3 Incidence of Malpresentation from 28 Weeks Gestation through Term | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If external version at term is to be attempted, it should be done in the labor and delivery suite, using monitoring of the fetal position and heart rate by ultrasound. Both regional anesthesia and a dose of a tocolytic medication have been shown to increase the success rate of ECV. Epidural analgesia appears to be superior to spinal analgesia. The most recent Cochrane review found that ECV failure, noncephalic births, and cesareans were reduced in two trials with epidural but not in three with spinal analgesia. Two theories for this difference have been advanced. The large volume preloading associated with an epidural may increase the amniotic fluid volume. The local anesthetic doses used in the epidural studies also may have resulted in significant abdominal wall relaxation. This same Cochrane review concludes that, “there is evidence to support the use of tocolysis in clinical practice to reduce the failure rate of ECV at term. Whether tocolysis should be used routinely or selectively, when initial ECV attempts fail, has not been adequately addressed.” A number of the studies of tocolysis for ECV used intravenous ritodrine, an agent no longer available in the United States. One readily available agent on most labor and delivery units is terbutaline. In 1997, Fernandez and colleagues reported a prospective, randomized, controlled trial showing that terbutaline (0.25 mg) administered subcutaneously, 15 to 30 minutes before the attempt, doubled their ECV success rate.

In the authors’ practice, terbutaline is used, and attempts at ECV are scheduled at 37 weeks gestation. Regardless of the fetal presentation after the attempt, the patient is then discharged and delivered at a future date. An alternative approach may be to attempt ECV at 38 weeks gestation after an epidural is placed. If the version is successful, proceed with induction of labor. If unsuccessful, cesarean delivery could then be performed with only a small risk of fetal lung immaturity.

The safety of ECV is well documented. In a recent review of 44 studies by Collaris, published between 1990 and 2002, with a total of 7,377 patients, the most frequently reported complications were transient abnormal fetal heart rate patterns (5.70%), fetomaternal transfusion (3.70%), vaginal bleeding (0.47%), emergency cesarean (0.43%), persisting pathologic fetal heart rate patterns (0.37%), and placental abruption (0.12%). The incidence of perinatal mortality was 0.16%. None of these studies used any anesthesia. In a review of six studies published within the same time period that included 1,170 patients in whom anesthesia was utilized, complications of ECV were more frequent, including transient abnormal fetal heart rate patterns (11.7%), persisting pathologic fetal heart rate patterns (4.36%), vaginal bleeding (3.67%), emergency cesarean (5.30%), and placental abruption (0.51%). The majority of these complications occurred in the study with the largest number of patients. If this study is excluded, the rates of these complications are similar to those in the studies in which anesthesia was not used.

Lau and associates reported a series of 243 women who underwent attempts at external version. Regression analysis identified three independent predictors of failed version: (a) engaged presenting part, (b) difficulty palpating the fetal head, and (c) nulliparity. The chance of success was 0% if all three variables were present, <20% if any two were present, 30% to 60% if only one was present, and 94% if none was present. Interestingly, placental location, position of the fetal spine, attitude of the fetal legs, and maternal obesity were not significant variables for predicting successful version when controlling for the other variables.

The Cochrane Database review of ECV at term concludes that “the chance of breech birth and cesarean section may be substantially reduced by attempting ECV at term. There is sound reason to use ECV at term, with appropriate cautions.” The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends, in Committee Opinion No. 340, July 2006, that “obstetricians should offer and perform external cephalic version whenever possible.” It should be noted that successful external version does not reduce the cesarean rate to that found in spontaneous vertex presentations. In 2004, Verzina and colleagues published a case-controlled study in which each patient who underwent successful ECV was compared with the next parturient of the same parity with a vertex presentation at term. The rates of cesarean delivery in the ECV groups of both nulliparous women (29.8% vs. 15.9%, P <0.001) and multiparous women (15.9% vs. 4.7%, P <0.001) were significantly higher when compared with the control groups. Earlier that same year, Chan and colleagues published a meta-analysis that concluded that the intrapartum cesarean delivery rate after successful ECV is twice the rate seen with spontaneous cephalic presentations.

Active labor and ruptured membranes are contraindications to the procedure. Relative contraindications include an engaged presenting part and an estimated fetal weight of ≥4,000 g. Whether a previous cesarean contraindicates

attempts at external version is uncertain, but in modern practice, delivery of breech fetus in a woman with a previous cesarean by elective repeat cesarean seems reasonable.

attempts at external version is uncertain, but in modern practice, delivery of breech fetus in a woman with a previous cesarean by elective repeat cesarean seems reasonable.

TABLE 22.4 Neonatal Morbidity, Planned Vaginal Delivery versus Planned Cesarean Typical (Odds Ratio and 95% Confidence Interval) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Management of Delivery

Term Breech Presentation

In 1993, Cheng and Hannah published a critical review of the literature on singleton term breech pregnancies, reviewing all articles in the English language literature between 1966 and 1992. They found that there were only 24 studies that presented outcome data in sufficient detail to be analyzable according to the intended mode of delivery. Of these 24 reports, only two were randomized trials1; eight were prospective cohort studies and 14 were randomized cohort studies. Twenty-two of these studies, including both prospective trials, did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference in corrected perinatal mortality between those patients for whom a vaginal delivery was planned and those for whom a cesarean was planned. Two series did show significantly worse outcome among those for whom vaginal delivery was planned. When the authors combined all of the data, they produced a “typical odds ratio” for perinatal mortality of 3.86, (95% confidence interval [CI] of 2.22 to 6.69) in the planned vaginal delivery group. Their data on low 5-minute Apgar scores, birth trauma, and short- and long-term neonatal morbidity were similar to the data on perinatal mortality, in that the majority of individual studies did not find a difference between those for whom vaginal birth was planned and those for whom cesarean was planned, but when the studies were combined, the planned vaginal delivery group fared worse in all categories (Table 22.4). The authors of this review carefully pointed out all of the flaws in the papers they reviewed and concluded that most of these studies were too poorly done to allow definitive conclusions. They ended their paper by stating that “the only way to obtain more definitive information regarding the effectiveness of a policy of elective cesarean vs. that of a trial of labor in women with breech presentation at term is to mount an appropriately sized, randomized controlled trial. In the absence of such a trial, a policy of elective cesarean delivery appears to be a reasonable option for the woman with breech presentation at term.”

The Term Breech Trial organized by Hannah and associates is such a trial. The trial was carried out between January 1997 and April 2000 in 121 hospitals in 26 countries. Sixteen were industrialized nations with low perinatal mortality rates, and ten were underdeveloped countries with high perinatal mortality rates. The results of this trial were published in 2000 and will be presented here in considerable detail because of the uniqueness and importance of the study.

Patients were eligible for the trial if they were at 37 or more weeks of singleton gestation with a frank or complete breech. Women were excluded for clinical or radiographic evidence of pelvic inadequacy (91% of subjects in both groups had only clinical evaluation of the pelvis), if the fetus was estimated to weigh >4,000 g either by clinical estimation or by ultrasonography (60% of subjects had sonography, 40% had clinical evaluations of fetal weight), if hyperextension of the fetal neck was felt to be present by clinical exam (31% of subjects) or ultrasonography (69% of subjects), if there was a contraindication to labor or vaginal delivery, or if there were fetal malformations incompatible with life or which might predispose to mechanical problems with vaginal delivery. The labor protocol permitted induction and augmentation of labor for usual indications and called for either continuous electronic fetal monitoring or intermittent auscultation every 15 minutes in the first stage of labor and every 5 minutes in the second. Adequate labor progress was defined as a rate of cervical dilatation of ≥0.5 cm per hour in the active phase, descent of the breech to the pelvic floor within 2 hours of the second stage, and imminent delivery within 1 hour of active pushing. The method of vaginal delivery was spontaneous or assisted; total breech extraction was not permitted. Most importantly, all vaginal deliveries were to be attended by a clinician experienced with vaginal breech delivery (self-defined with confirmation by the individual’s department head).

The primary outcomes measured were perinatal/ neonatal mortality and serious neonatal morbidity. The secondary outcomes measured were maternal mortality and serious maternal morbidity (Table 22.5). Power analysis prior to the study calculated a required randomization of 2,800 subjects. An interim analysis of the first 1,600 births revealed a clear advantage for planned cesarean, and therefore, recruitment was stopped at 2,088 women (488

additional women had been enrolled while the interim analysis of the first 1,600 was in progress). In the final analysis, the rate of perinatal mortality and morbidity was 1.6% in the planned cesarean group and 5.0% in the planned vaginal delivery group (relative risk [RR] 0.33, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.56, P <0.0001). Considering perinatal mortality alone, the respective rates for cesarean and vaginal delivery were 0.3% and 1.3% (RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.81, P <.01). Similar data for neonatal morbidity alone were 1.4% and 3.8% (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.65, P <0.0003). For every subcategory of neonatal morbidity, infants in the planned cesarean group fared significantly better than those in the planned vaginal delivery group. Most interestingly, the improvement in neonatal outcome with planned cesarean was better in the countries with already low perinatal mortality rates. The authors determined that in industrialized nations, one case of neonatal mortality or serious morbidity could be avoided for every seven additional cesareans, whereas in underdeveloped countries as many as 39 additional cesareans might be needed to avoid one dead or compromised baby. For the entire population studied, the number of additional cesareans needed to avoid one dead or seriously injured baby was 14. The authors’ finding of a significant advantage for planned cesarean birth was maintained even after excluding labors that were prolonged, induced, or augmented and after correcting for whether or not epidural anesthesia was used. Finally, and equally importantly, the authors found no differences between the groups in terms of maternal mortality or serious morbidity; there were no differences in maternal morbidity whether the various morbid conditions were totaled or considered separately.

additional women had been enrolled while the interim analysis of the first 1,600 was in progress). In the final analysis, the rate of perinatal mortality and morbidity was 1.6% in the planned cesarean group and 5.0% in the planned vaginal delivery group (relative risk [RR] 0.33, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.56, P <0.0001). Considering perinatal mortality alone, the respective rates for cesarean and vaginal delivery were 0.3% and 1.3% (RR 0.23, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.81, P <.01). Similar data for neonatal morbidity alone were 1.4% and 3.8% (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.65, P <0.0003). For every subcategory of neonatal morbidity, infants in the planned cesarean group fared significantly better than those in the planned vaginal delivery group. Most interestingly, the improvement in neonatal outcome with planned cesarean was better in the countries with already low perinatal mortality rates. The authors determined that in industrialized nations, one case of neonatal mortality or serious morbidity could be avoided for every seven additional cesareans, whereas in underdeveloped countries as many as 39 additional cesareans might be needed to avoid one dead or compromised baby. For the entire population studied, the number of additional cesareans needed to avoid one dead or seriously injured baby was 14. The authors’ finding of a significant advantage for planned cesarean birth was maintained even after excluding labors that were prolonged, induced, or augmented and after correcting for whether or not epidural anesthesia was used. Finally, and equally importantly, the authors found no differences between the groups in terms of maternal mortality or serious morbidity; there were no differences in maternal morbidity whether the various morbid conditions were totaled or considered separately.

TABLE 22.5 Primary and Secondary Outcomes in the Term Breech Trial | |

|---|---|

|