Breast Masses

Jennifer C. Edman and Mary-Ann Shafer

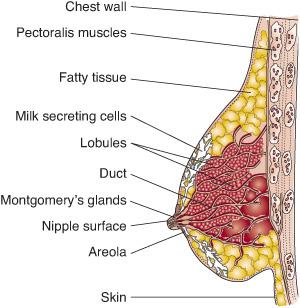

The normal anatomy of the breast is shown in Figure 74-1. A variety of benign breast lesions occur in the female adolescent. The most typical presentation is a self-detected, asymptomatic mass. Complaints such as bloody discharge, nipple retraction, or skin dimpling are rare.

ANATOMIC CHANGES AND CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES

Breast asymmetry, a common condition in which one breast develops earlier or grows more rapidly than the other, usually occurs between sexual maturity rating (SMR) 2 and 4 and persists into adulthood in 25% of women. Rare congenital abnormalities of the breast include amastia (absent breast, associated with chest wall deformities such as pectus excavatum or Poland syndrome) and athelia (absent nipple). Polymastia (accessory breast tissue) and polythelia (accessory nipples) occur along the mammalian nipple line in 1% to 2% of girls and may be inheritable conditions. Breast atrophy developing after thelarche can be one sign of an eating disorder or other chronic illness such as scleroderma. The associated loss of both fat and glandular tissue in the breast results from significant weight loss. Virginal (juvenile) hypertrophy, the massive enlargement of one or both breasts caused by either increased tissue sensitivity to pubertal hormones or endogenous production of hormones from within breast cells, can be associated with a variety of problems, including headache, neck and back pain, dermatitis, embarrassment, and psychological difficulties. Reduction mammoplasty after completion of breast maturation may be indicated in female adolescents with severe virginal hypertrophy. Medications such as medroxyprogesterone and danazol are not effective in the reduction of mammary hyperplasia in adolescents.1,2

CYSTS, FIBROCYSTIC CHANGES, AND FIBROADENOMAS

The most common breast masses in adolescents are solitary cysts, fibrocystic change, and fibroadenomas. Masses resulting from inflammation or trauma occur less frequently. Cancer is rare among female adolescents. A solitary cyst contains sterile fluid. Over half resolve spontaneously within 2 to 3 months, so fine-needle aspiration or biopsy is often unnecessary. Recurrent or multiple cysts in the adolescent may represent early fibrocystic change.

Fibrocystic change (benign proliferative breast change) is a physiological response of breast tissue to cyclic hormonal activity. The result is a dilation and proliferation of duct epithelium to form gross cysts. A benign condition more common during the third and fourth decades, fibrocystic change may occur during adolescence. Bilateral breast pain in the upper outer quadrants beginning in the premenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle and subsiding thereafter is the typical presentation. Physical examination reveals areas of diffuse, cordlike thickening as well as discrete mobile lesions, which often increase in size during the premenstrual period. Early studies suggesting that methylxanthines (coffee, chocolate, tea, cola) are factors in the development or exacerbation of fibrocystic change have not been substantiated.3,4 Supportive care, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents for pain and a well-fitting supportive bra, is the most common approach to treatment. Oral contraceptives reduce symptoms in 70% to 90% of cases.4

FIGURE 74-1. Breast anatomy.

The majority (70–95%) of adolescent breast masses that undergo biopsy are identified as fibroadenomas.2 Four types of fibroadenomas have been described: common fibroadenomas, juvenile fibroadenomas, giant fibroadenomas, and cystosarcoma phyllodes. A fibroadenoma is a benign proliferation of stromal elements, ducts, and acini. Physical examination reveals a rubbery, painless, well-demarcated mass, 1 to 3 cm in size, usually located in the upper outer quadrant of the breast. Fibroadenomas may regress spontaneously but usually persist and may require excisional biopsy. Peak incidence occurs during late adolescence, but fibroadenomas may present up to 2 years before menarche.5-9 Multiple and recurrent fibroadenomas may occur, but malignant potential has not been established.1,2

Juvenile fibroadenoma, a histologically similar lesion but with less well-defined edges, presents as a rapidly enlarging breast mass that can reach immense proportions (> 5 cm, up to 15–20 cm). Giant fibroadenomas are found most commonly in young African American women. Complete excision is curative. Cystosarcoma phyllodes is a rare, rapidly growing lesion that is usually large, well-demarcated, and has a small potential for malignancy. The large phyllodes tumor may cause overlying skin to become stretched and shiny with distended veins, erythema, and even ulceration.2,4Intraductal papilloma, a slow-growing benign tumor located under the areola, often presents with a serous or bloody nipple discharge.

BREAST CANCER

Primary breast cancer is rare in teenagers. Only 0.2% to 2% of all breast cancers occur before 25 years of age.2,6-8 More than 60% of breast cancers in adolescents are not primary breast tumors but arise metastatically from distant sites (eg, lymphoma) or locally from nonbreast tissue (eg, angiosarcomas).1,2,6,7 Cancer, in contrast to benign breast disease, is characterized by a hard, fixed mass beneath the nipple. Approximately one third to one half of cases have a positive family history. Breast cancer–associated genes (BRCA-1 or BRCA-2) account for only a small fraction of cancers (5–9%).2,4 Risk factors for the development of adult breast cancer established during adolescence include menarche before age 12 years and cancer treatment–related radiation in the breast area (eg, for lymphoma).5,9 There is no clear association between use of oral contraceptives and later development of breast adenocarcinoma.2,5

OTHER BREAST MASSES

A contusion may present as a poorly defined tender mass, with or without overlying hematoma. Less than half of patients will give a history of antecedent trauma. Contusions usually resolve over several weeks but may persist for several months. Occasionally, scar tissue or fat necrosis develops, resulting in small areas of calcification. Treatment consists of local excision. Trauma may also draw attention to a preexisting lesion unrelated to the injury.

Mastitis, or breast infection, presents with the rapid onset of unilateral pain and localized inflammation. Infection is more common in newborns and lactating women but can occur in adolescents secondary to trauma, nipple piercing, ductal abnormalities, or reduced immune defenses.4Staphylococcus aureus is the most common etiologic organism. The initial management of mastitis includes systemic antibiotics, warm compresses, and analgesia. Acute mastitis may lead to fluctuance and abscess formation. Circumareolar incision and drainage is then indicated. Abscess formation must be considered with persistent, unresponsive mastitis.

ASSESSMENT

When assessing a breast mass, the history should identify previous trauma, fever, weight loss, and nipple discharge. A family history of breast disease and the nature of any previous lesions should be obtained. A menstrual history of cyclic pain can be helpful in diagnosing fibrocystic changes. The history often elicits the use of oral contraceptive pills or other hormonal agents that can alter the breast. The physical examination includes assessment of SMR to avoid confusing the normal breast bud (especially if unilateral) with an abnormal mass. The size, location, and characteristics of the lesion should be described. Tenderness, warmth, and lymphadenopathy are consistent with infection. A hard, fixed lesion with overlying skin changes must be evaluated for cancer. Prolactin, thyroid, and gonadotropin levels are obtained to evaluate the symptom of galactorrhea.

Management of a suspected benign breast mass in an adolescent begins with reassurance and an observation period of 1 to 3 months. During this time, any change that occurs with the menstrual cycle should be noted. Masses that persist beyond this time should be referred for further evaluation. Fine needle aspiration will distinguish a cystic from a solid lesion. Any aspirate obtained should undergo cytologic evaluation.6 A cyst will collapse after aspiration, yielding a clear-yellow or brownish fluid, and the breast should be reexamined in 3 months.1 Breast core biopsy is a newer method to obtain tissue diagnosis.5,6 Excisional biopsy is indicated for a large solid or growing mass or one that yields an abnormal aspirate. The purpose of excision is to obtain a definitive diagnosis, avoid cosmetic deformity, and alleviate patient anxiety. Normal breast tissue can be spared because there is no need to remove a wide margin.1,5

Mammography is rarely indicated in the evaluation of a palpable mass in an adolescent. The normally dense parenchymal tissue in the adolescent breast makes interpretation difficult. Mammography is not indicated for screening in this age group because of the low prevalence of malignancy. Ultrasonography is useful to differentiate between solid and cystic masses and to guide the fine needle aspiration.1,2,4,8,10

The value of teaching breast self-examination to adolescents remains controversial; its benefits have not been proven. The US Preventive Services Task Force concluded insufficient evidence exists to recommend for or against BSE, while the American Cancer Society still recommends that women begin monthly BSE at age 20.11-13 Others recommend young women carrying the BRCA-1 or BRCA-2 genes begin monthly BSE at age 18 to 21 years.4 Some professionals argue that routine BSE in adolescents creates unnecessary anxiety and serves to identify a greater number of benign lesions. Teaching modified BSE may be a valuable educational component in the routine physical examination of the adolescent by leading to a discussion of normal development.9

ADOLESCENT GYNECOMASTIA

Pubertal gynecomastia, the glandular enlargement of breast tissue in males, is a common complaint (see eFig. 74.1  ). Gynecomastia, which occurs transiently in 40% to 60% of 10-to 16-year-old boys and peaks in incidence at SMR 2 to SMR 4 (age 14 years), results from a decreased ratio of androgen to estrogen and a change in end-organ receptor sensitivity. The breast tissue is frequently firm, tender, and often asymmetric. Spontaneous resolution occurs in 90% of boys within 3 years. Rare causes of gynecomastia include endogenous states of estrogen excess, such as testicular, adrenal, or pituitary tumors; hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism; hepatic disorders; refeeding poststarvation; endogenous androgen deficiency states such as hypogonadism, Klinefelter syndrome, renal hemodialysis, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia; and specific drugs, including estrogen, testosterone, anabolic steroids, human chorionic gonadotropins, tricyclic antidepressants, insulin, alcohol, marijuana, amphetamines, metha-done, cimetidine, digitalis, and cytotoxic agents among others. Pseudogynecomastia (fatty tissue or muscle development), frequently confused with true gynecomastia (glandular enlargement), can be distinguished by comparing the consistency of the breast tissue with that of adipose tissue in the anterior axillary fold.

). Gynecomastia, which occurs transiently in 40% to 60% of 10-to 16-year-old boys and peaks in incidence at SMR 2 to SMR 4 (age 14 years), results from a decreased ratio of androgen to estrogen and a change in end-organ receptor sensitivity. The breast tissue is frequently firm, tender, and often asymmetric. Spontaneous resolution occurs in 90% of boys within 3 years. Rare causes of gynecomastia include endogenous states of estrogen excess, such as testicular, adrenal, or pituitary tumors; hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism; hepatic disorders; refeeding poststarvation; endogenous androgen deficiency states such as hypogonadism, Klinefelter syndrome, renal hemodialysis, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia; and specific drugs, including estrogen, testosterone, anabolic steroids, human chorionic gonadotropins, tricyclic antidepressants, insulin, alcohol, marijuana, amphetamines, metha-done, cimetidine, digitalis, and cytotoxic agents among others. Pseudogynecomastia (fatty tissue or muscle development), frequently confused with true gynecomastia (glandular enlargement), can be distinguished by comparing the consistency of the breast tissue with that of adipose tissue in the anterior axillary fold.

Diagnosis of gynecomastia is based on the typical history and examination and the exclusion of other causes of gynecomastia. The history includes a review of current medications and illicit drug use (eg, marijuana use has been associated with gynecomastia). Physical assessment should describe the SMR and findings of the testicular examination as well as the amount and quality of breast tissue present. If glandular tissue is less than 4 cm (eg, SMR 2–3 female breast), reassurance is the most appropriate treatment. In contrast, pubertal macrogynecomastia resembles female SMR 3 to SMR 5 breasts, extends more than 5 cm, and usually does not regress spontaneously. A surgical referral is indicated when pubertal gynecomastia has a prolonged course (> 2 years), causes psychological impairment, or if macrogynecomastia is present. Medications such as danazol, tamoxifen, and testolactone are not generally recommended for adolescents because of their side-effect profiles, lack of documented efficacy, and frequent return of breast tissue after the drug is discontinued.2,14,15

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree