Bleeding Complications

Severe and hemodynamically significant bleeding that requires transfusion is one of the most important complications of surgery. Two factors are particularly stressful for a patient having any operation: prolonged surgical time and major blood loss. Ideally, therefore, surgery should be performed swiftly. Speed and limited blood loss are not necessarily complementary, however, because careful, bloodless operating is time-consuming. On the other hand, major bleeding leads to loss of anatomical overview, prolongs the operation, and can contribute indirectly to injury of other structures. Every surgeon will have to find an individual compromise for the patient′s benefit. The clinical end result of uncontrolled bleeding is shock and thus a life-threatening situation.

Intraoperative Bleeding—Abdominal Procedures

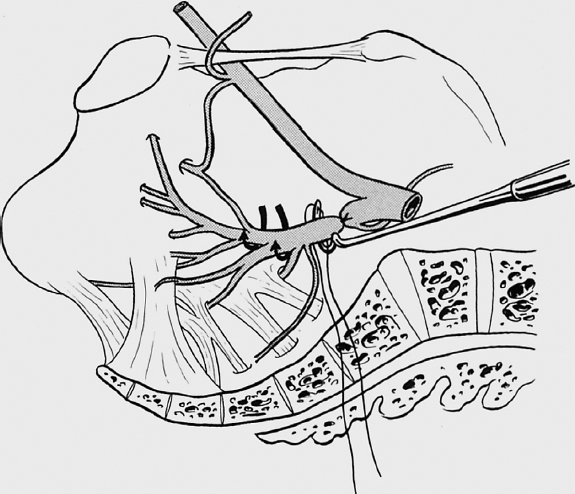

Common gynecological open abdominal procedures include hysterectomy when the uterus is very large, cancer surgery, and nonlaparoscopic operations for endometriosis. The most important sources of bleeding are usually the ovarian arteries in the infundibulopelvic ligament (suspensory ligament of the ovary) and the two uterine arteries. Only adequately dissected vessels can be clamped and ligated securely. Careful dissection of the bladder, bowel, and adhesions as well as exact visualization of the ureters are therefore the most important prerequisites for rapid control of unexpected bleeding. The rule is that an operation step that involves a risk of bleeding should always be the last step after the site has been safely dissected. A good operative technique prevents bleeding, and poor visualization favors bleeding. Bleeding in the region of the pelvic wall, in particular, can require complete ureterolysis and lateral division of the uterine artery at its origin from the internal iliac artery.

Intraoperative Bleeding—Vaginal Procedures

Bleeding after vaginal operations can be particularly undesirable on account of the limited access.

Vaginal margin. During a vaginal hysterectomy, there may be considerable bleeding from the vaginal margin even at the start of the operation. On the one hand, suction should be readily available to optimize vision; on the other hand, initial hemostatic techniques such as circular injection of the ectocervix with a vasoconstrictor substance (“liquid tourniquet”) may help. An old hemostatic technique consists of a continuous suture (“gathering”) of the posterior vaginal margin right at the start of the operation.

Parametrial resection margin. The basic rules of careful clamping and secure ligature apply for hemostasis of the parametrial resection margin, especially the vascular part. Moving toward the ovarian ligament itself and the immediately adjacent uterine branch of the ovarian artery, it must then be ensured that excessive traction on the uterus does not lead to tearing of the tissue bridge with bleeding retraction of the artery. The transfixion ligatures in the sacrouterine ligament and ovarian ligament (or infundibulopelvic ligament in the case of adnexectomy) are left long so that the entire series of parametrial divisions between them can be inspected and additional sutures can be placed if necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree