Barrier Methods of Contraception and Withdrawal

|

Barrier methods of contraception have been the most widely used contraceptive techniques throughout recorded history. These methods, the oldest of methods, are now being thrust into the forefront as we respond to the personal and social impact of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). A new need for sexual safety has brought modern respect and new developments to the condom, while the other barrier methods continue to serve well for appropriate couples. Withdrawal is also an ancient method of contraception that deserves modern understanding and appreciation.

History of Barrier Methods

The use of vaginal contraceptives is probably as ancient as Homo sapiens. References to sponges and plugs appear in the earliest of writings. However, the diaphragm and the cervical cap were not invented until the late 1800s, the same time period that saw the beginning of investigations with spermicidal agents.

Intravaginal contraception was widespread in isolated cultures throughout the world. The Japanese used balls of bamboo paper, Islamic women used willow leaves, and the women

in the Pacific Islands used seaweed. References can be found throughout ancient writings to sticky plugs, made of gumlike substances, to be placed in the vagina prior to intercourse. In preliterate societies, an effective method had to have been the result of trial and error, with some good luck thrown in.

in the Pacific Islands used seaweed. References can be found throughout ancient writings to sticky plugs, made of gumlike substances, to be placed in the vagina prior to intercourse. In preliterate societies, an effective method had to have been the result of trial and error, with some good luck thrown in.

How was contraceptive knowledge spread? Certainly, until modern times, individuals did not consult clinicians for contraception. Contraceptive knowledge was folklore, undoubtedly perpetuated by the oral tradition. The social and technical circumstances of ancient times conspired to make communication of information very difficult. But even when knowledge was lacking, the desire to prevent conception was not. Hence, the widespread use of potions, body movements, and amulets; all of which can be best described as magic.

Egyptian papyri dating from 1850 B.C. refer to plugs of honey, gum, acacia, and crocodile dung. The descriptions of contraceptive techniques by Soranus are viewed as the best in history until modern times.1 Soranus of Ephesus lived from 98 to 138 and has often been referred to as the greatest gynecologist of antiquity. He studied in Alexandria, and practiced in Rome. His great text was lost for centuries and was not published until 1838. Soranus gave explicit directions regarding how to make concoctions that probably combined a barrier with spermicidal action. He favored making pulps from nuts and fruits (probably very acidic and spermicidal) and advocated the use of soft wool placed at the cervical os. He described up to 40 different combinations.

The earliest penis protectors were just that, intended to provide prophylaxis against infection. In 1564, Gabriello Fallopius, one of the early authorities on syphilis, described a linen condom that covered the glans penis. The linen condom of Fallopius was followed by full covering with animal skins and intestines, but use for contraception cannot be dated to earlier than the 1700s.

There are many versions accounting for the origin of the word condom. Most attribute the word to a Dr. Condom, a physician in England in the 1600s. The most famous story declares that Dr. Condom invented the sheath in response to the annoyance displayed by Charles II at the number of his illegitimate children. All attempts to trace this physician have failed. This origin of the word can neither be proved nor disproved. Condom may be derived from the Latin condon that means “receptacle.”1 By 1800, condoms were available at brothels throughout Europe, but nobody wanted to claim responsibility. The French called the condom the English cape; the English called condoms French letters.

The vulcanization of rubber revolutionized transportation and contraception. Vulcanization of rubber dates to 1844, and, by 1850, rubber condoms were available in the U.S. The introduction of liquid latex and automatic machinery ultimately made reliable condoms both plentiful and affordable.

Diaphragms first appeared in publications in Germany in the 1880s. A practicing German gynecologist C. Haase wrote extensively about his diaphragm, using the pseudonym Wilhelm P.J. Mensinga. The Mensinga diaphragm retained its original design with little change until modern times.

The cervical cap was available for use before the diaphragm. A New York gynecologist E.B. Foote wrote a pamphlet describing its use around 1860. By the 1930s, the cervical cap was the most widely prescribed method of contraception in Europe. Why was the cervical cap not accepted in the U.S.? The answer is not clear. Some blame the more prudish attitude toward sexuality as an explanation for why American women had difficulty learning self-insertion techniques.

Scientific experimentation with chemical inhibitors of sperm began in the 1800s. By the 1950s, more than 90 different spermicidal products were being marketed, and some of them were used in the first efforts to control fertility in India.2 With the availability of

the intrauterine device and the development of oral contraception, interest in spermicidal agents waned, and the number of products declined.

the intrauterine device and the development of oral contraception, interest in spermicidal agents waned, and the number of products declined.

In the last decades of the 1800s, condoms, diaphragms, pessaries, and douching syringes were widely advertised; however, they were not widely used. It is only since 1900 that the knowledge and application of contraception have been democratized, encouraged, and promoted. And it is only since 1960 that contraception teaching and practice became part of the program in academic medicine, but not without difficulty. In the 1960s, Duncan Reid, chair of obstetrics at Harvard Medical School, organized and cared for women in a clandestine clinic for contraception. In “Dr. Reid’s Clinic” at the Boston Lying-In Hospital, women were able to receive contraceptives not available elsewhere in the city.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1961, C. Lee Buxton, chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Yale Medical School, and Estelle Griswold, the 61-year-old executive director of Connecticut Planned Parenthood, opened four Planned Parenthood clinics in New Haven, in a defiant move against the current Connecticut law. In an obvious test of the Connecticut law, Buxton and Griswold were arrested at the Orange Street clinic, in a prearranged scenario scripted by Buxton and Griswold at the invitation of the district attorney. They were found guilty and fined $100, but imprisonment was deferred because the obvious goal was a decision by the United States Supreme Court. Buxton was forever rankled by the trivial amount of the fine. On June 7, 1965, the Supreme Court voted 7-2 to overturn the Connecticut law on the basis of a constitutional right of privacy. It was not until 1972 and 1973 that the last state laws prohibiting the distribution of contraceptives were overthrown.

Risks and Benefits Common to All Barrier Methods

Barrier methods (condoms and diaphragms) provide protection (about a 50% reduction) against sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID).6,7,8,9 and 10 This includes infections due to chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomonas, herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); however, only the condom has been proven to prevent HIV infection. STI protection has a beneficial impact on the risk of tubal infertility and ectopic pregnancy.8,11 There have been no significant clinical studies on STIs and cervical caps or the female condom, but these methods should be effective. Women who have never used barrier methods of contraception are almost twice as likely to develop cancer of the cervix.11,12 The risk of toxic shock syndrome is increased with female barrier methods, but the actual incidence is so rare that this is not a significant clinical consideration.13 Women who have had toxic shock syndrome, however, should be advised to avoid barrier methods.

Barrier Methods and Preeclampsia

An initial case-control study indicated that methods of contraception that prevented exposure to sperm were associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia.14 This was not confirmed in a careful analysis of two large prospective pregnancy studies.15 This latter conclusion was more compelling in that it was derived from a large, prospective, cohort data base.

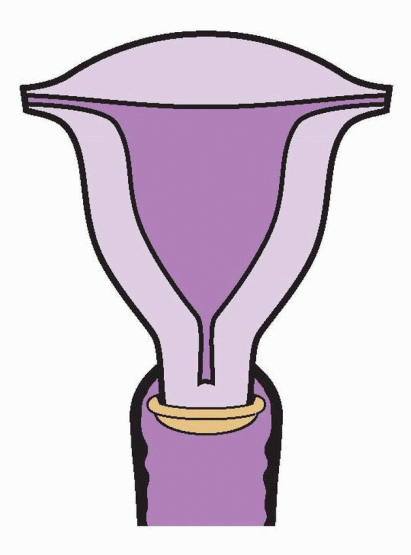

The Diaphragm

The first effective contraceptive method under a woman’s control was the vaginal diaphragm. Distribution of diaphragms led to Margaret Sanger’s arrest in New York City in 1918. This was still a contentious issue in 1965 when the Supreme Court’s decision in Griswold vs. Connecticut ended the ban on contraception in that state. By 1940, one-third of contracepting American couples were using the diaphragm. This decreased to 10% by 1965 after the introduction of oral contraceptives and intrauterine devices and fell to about 1.9% in 1995, and today, diaphragm use has nearly disappeared in the U.S.

Efficacy

Failure rates for diaphragm users vary from as low as 2% per year of use to a high of 23%. The typical use failure rate after 1 year of use is 16%.3,4 and 5 Older, married women with longer use achieve the highest efficacy, but young women can use diaphragms very successfully if they are properly encouraged and counseled. There have been no adequate studies to determine whether efficacy is different with and without spermicides.16

Side Effects

The diaphragm is a safe method of contraception that rarely causes even minor side effects. Occasionally, women report vaginal irritation due to the latex rubber or the spermicidal jelly or cream used with the diaphragm. Less than 1% discontinue diaphragm use for these reasons. Urinary tract infections are 2-3-fold more common among diaphragm users than among women using oral contraception.17,18 Possibly, the rim of the diaphragm presses against the urethra and causes irritation that is perceived as infectious in origin, or true infection may result from touching the perineal area or from incomplete emptying of the bladder. It is more probable that spermicides used with the diaphragm can increase the risk of bacteriuria with E. coli, perhaps due to an alteration in the normal vaginal flora.19 Clinical experience suggests that voiding after sexual intercourse is helpful, and, if necessary, a single postcoital dose of a prophylactic antibiotic can be recommended. Postcoital prophylaxis is effective, using trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole (1 tablet postcoitus), nitrofurantoin (50 or 100 mg postcoitus), or cephalexin (250 mg postcoitus).

Improper fitting or prolonged retention (beyond 24 h) can cause vaginal abrasion or mucosal irritation. There is no link between the normal use of diaphragms and the toxic shock syndrome.20 It makes sense, however, to minimize the risk of toxic shock by removing the diaphragm after 24 h and during menses.

Benefits

Diaphragm use reduces the incidence of cervical gonorrhea, trichomonas, and chlamydia,21 pelvic inflammatory disease,8,22 and tubal infertility.6,11 There are no data, as of yet, regarding the effect of diaphragm use on the transmission of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) virus HIV, but because the vagina remains exposed, the diaphragm is unlikely to protect against HIV. A clinical trial demonstrated no added benefit with a diaphragm against HIV when used with condoms.23 An important advantage of the diaphragm is low cost. Diaphragms are durable and with proper care can last for several years.

Choice and Use of the Diaphragm

There are three major types of latex diaphragms, and most manufacturers produce them in sizes ranging from 50 to 105 mm diameter, in increments of 2.5 to 5 mm. Most women use sizes between 65 and 80 mm. The SILCS diaphragm, is a silicone barrier used with a contraceptive gel.24 It comes in one size that fits most women, and, therefore, interaction with a clinician and the requirement for fitting can be avoided. The Milex Wide Seal diaphragm is also made of silicone and comes in eight sizes that require fitting.

The latex diaphragm made with a flat metal spring or a coil spring remains in a straight line when pinched at the edges. This type is suitable for women with good vaginal muscle tone and an adequate recess behind the pubic arch. However, many women find it difficult to place the posterior edge of these flat diaphragms into the posterior cul-de-sac and over the cervix.

Arcing diaphragms are easier to use for most women. They come in two types. The All-Flex type bends into an arc no matter where around the rim the edges are pinched together. The hinged type must be pinched between the hinges to form a symmetrical arc. The hinged type forms a narrower shape when pinched together and, thus, may be easier for some women to insert. The arcing diaphragms allow the posterior edge of the diaphragm to slip more easily past the cervix and into the posterior cul-de-sac. Women with poor vaginal muscle tone, cystocele, rectocele, a long cervix, or an anterior cervix of a retroverted uterus use arcing diaphragms more successfully.

Fitting

Successful use of a diaphragm depends on proper fitting. The clinician must have available aseptic fitting rings or diaphragms themselves in all diameters. These devices should be scrupulously disinfected by soaking in a bleach solution. At the time of the pelvic examination, the middle finger is placed against the vaginal wall and the posterior cul-de-sac, while the hand is lifted anteriorly until the pubic symphysis abuts the index finger. This point is marked with the examiner’s thumb to approximate the diameter of the diaphragm. The corresponding fitting ring or diaphragm is inserted, and the fit is assessed by both clinician and patient.

If the diaphragm is too tightly pressed against the pubic symphysis, a smaller size is selected. If the diaphragm is too loose (comes out with a cough or bearing down), the next larger size is selected. After a good fit is obtained, the diaphragm is removed by hooking the index finger under the rim behind the symphysis and pulling. It is important to instruct the patient in these procedures during and after the fitting. The patient should then insert the diaphragm, practice checking for proper placement, and attempt removal.

Timing

Diaphragm users need additional instruction about the timing of diaphragm use in relation to sexual intercourse and the use of spermicide. None of this advice has been rigorously assessed in clinical studies; therefore, these recommendations represent the consensus of clinical experience.

The diaphragm should be inserted no longer than 6 h prior to sexual intercourse. About a tablespoonful of spermicidal cream or jelly should be placed in the dome of the diaphragm prior to insertion, and some of the spermicide should be spread around the rim with a finger. The diaphragm should be left in place for approximately 6 h (but no more than 24 h) after coitus. Additional spermicide should be placed in the vagina before each additional episode of sexual intercourse while the diaphragm is in place.

Reassessment

Weight loss, weight gain, vaginal delivery, and even sexual intercourse can change vaginal caliber. The fit of a diaphragm should be assessed every year at the time of the regular examination.

Care of the Diaphragm

After removal, the diaphragm should be washed with soap and water, rinsed, and dried. Powders of any sort need not and should not be applied to the diaphragm. It is wise to use water to periodically check for leaks. Diaphragms should be stored in a cool and dark location.

The Cervical Cap

The cervical cap was popular in Europe long before its reintroduction into the United States. U.S. trials have demonstrated that the Prentif cervical cap is about as effective as the diaphragm but somewhat harder to fit (it comes in only four sizes) and more difficult to insert (it must be placed precisely over the cervix).25,26 Efficacy is significantly reduced in parous women.

The cervical latex Prentif cap has several advantages over the diaphragm. It can be left in place for a longer time (up to 48 h), and it need not be used with a spermicide. However, a tablespoonful of spermicide placed in the cap before application is reported to increase efficacy (to a 6% failure rate in the first year) and to prolong wearing time by decreasing the incidence of foul-smelling discharge (a common complaint after 24 h).26

The size of the cervix varies considerably from woman to woman, and the cervix changes in individual women in response to pregnancy or surgery. Proper fitting can be accomplished in about 80% of women. Women with a cervix that is too long or too short, or with a cervix that is far forward in the vagina, may not be suited for cap use. However, women with vaginal wall or pelvic relaxation, who cannot retain a diaphragm, may be able to use the cap.

Those women who can be fitted with one of the four sizes of the Prentif cap must first learn how to identify the cervix and then how to slide the cap into the vagina, up the posterior vaginal wall and onto the cervix. After insertion and after each act of sexual intercourse, the cervix should be checked to make sure that it is covered.

The cervical cap can be left in place for 2 days, but some women experience a foul-smelling discharge by 2 days. It must be left in place for at least 8 h after sexual intercourse in order to ensure that no motile sperm are left in the vagina. To remove the cap (at least 8 h after coitus), pressure must be exerted with a finger tip to break the seal. The finger is hooked over the cap rim to pull it out of the vagina. Bearing down or squatting or both can help to bring the cervix within reach of the finger.

The most common cause of failure is dislodgment of the cap from the cervix during sexual intercourse. There is no evidence that cervical caps cause toxic shock syndrome or dysplastic changes in the cervical mucosa.27 It seems likely (although not yet documented) that cervical caps would provide the same protection from sexually transmitted infections as the diaphragm.

The FemCap, made of nonallergenic silicone rubber, is shaped like a sailor’s hat, a design that allows a better fit over the cervix and in the vaginal fornices and provides a “brim” for easier removal.28 This cap may be easier to fit and use. There are three sizes, one for nulliparous women and larger sizes for women who have had a vaginal delivery. In a randomized trial, the pregnancy rate with FemCap was nearly 2-fold higher compared with a diaphragm.29

Lea’s Shield is a vaginal barrier contraceptive composed of silicone.30,31 This soft, pliable device comes in one size and fits over the cervix, held in place by the pressure of the vaginal wall around it. There is a collapsible valve that communicates with a 9-mm opening in the bowl that fits over the cervix. This valve allows equalization of air pressure during insertion and drainage of cervical secretions and discharge, permitting a snug fit over the cervix. A thick U-shaped loop attached to the anterior side of the bowl is used to stabilize the device during insertion and for removal. The thicker part of the device is shaped to fill the posterior fornix, thus contributing to its placement and stability over the cervix. The addition of a spermicide, placed in the bowl, is recommended. Lea’s Shield is designed to remain in place for 48 h after intercourse. Pregnancy rates are similar to other barrier methods, and no serious adverse effects have been reported.32

Lea’s Shield is a vaginal barrier contraceptive composed of silicone.30,31 This soft, pliable device comes in one size and fits over the cervix, held in place by the pressure of the vaginal wall around it. There is a collapsible valve that communicates with a 9-mm opening in the bowl that fits over the cervix. This valve allows equalization of air pressure during insertion and drainage of cervical secretions and discharge, permitting a snug fit over the cervix. A thick U-shaped loop attached to the anterior side of the bowl is used to stabilize the device during insertion and for removal. The thicker part of the device is shaped to fill the posterior fornix, thus contributing to its placement and stability over the cervix. The addition of a spermicide, placed in the bowl, is recommended. Lea’s Shield is designed to remain in place for 48 h after intercourse. Pregnancy rates are similar to other barrier methods, and no serious adverse effects have been reported.32

Ovés is a silastic cervical cap that is available in three sizes, with a loop for insertion and removal. Studies are limited to very small numbers of women, and there are no meaningful data on efficacy.33

The Contraceptive Sponge

The vaginal contraceptive sponge is a sustained-release system for a spermicide. The sponge also absorbs semen and blocks the entrance to the cervical canal. The “Today” sponge is a dimpled polyurethane disc impregnated with 1 g of nonoxynol-9. Approximately 20% of the nonoxynol-9 is released over the 24 h that the sponge is left in the vagina. “Protectaid” is a polyurethane sponge available in Canada and Hong Kong (it also can be purchased over the Internet) that contains three spermicides and a dispersing gel.34 The spermicidal agents are sodium cholate, nonoxynol-9, and benzalkonium chloride. This combination exerts antiviral actions in vitro.35 The dispersing agent, polydimethysiloxane, forms a protective coating over the entire vagina, providing sustained protection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree