Arterial Puncture and Catheterization

Susan B. Torrey

Richard A. Saladino

Introduction

Arterial blood sampling is necessary in the evaluation and management of many seriously ill or injured children (1,2). Precise measurements of pH, PO2, and PCO2 are important adjuncts in assessing respiratory and acid-base status. Although advances in noninvasive technology have reduced the need for arterial sampling, arterial blood may be required to clarify an abnormal pulse oximetry reading, and arterial access may be the most reliable source of blood in patients with difficult venous access. Arterial puncture is used for limited sampling and is a routine part of emergency medical care for pediatric patients.

Repeated access to arterial blood is best accomplished by catheterization of an artery. Indwelling catheters have long been used for hemodynamic monitoring in critically ill patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) (2,3,4). Arterial catheter placement is also important for monitoring the unstable ill or injured child in the emergency department (ED) (1). The most common indications for arterial catheterization are continuous blood pressure monitoring and repeated sampling of blood. Although noninvasive techniques for the continuous monitoring of arterial blood pressure are being developed, none are yet routinely available for use in infants and children (5). Data from both the pediatric ICU and ED show that arterial catheterization is a useful and appropriate procedure for children and that complications are few (1,2,3,4).

Arterial puncture is of moderate technical complexity. Nurses and respiratory therapists have been trained to perform this procedure in many institutions; however, it is more difficult to perform in infants and smaller children. Arterial catheterization in children is technically complex and should be performed by health care providers specifically trained in the technique, usually physicians. Both arterial puncture and catheterization can be performed in children of all ages as indicated by their clinical condition.

Anatomy

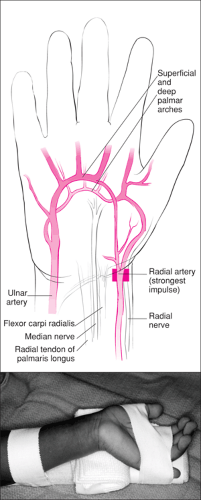

Radial Artery

The radial artery is the most frequently used artery for both puncture and cannulation. Collateral circulation in the wrist and hand is provided by the superficial and deep palmar arches (6). The superficial palmar arch is formed by the superficial branch of the radial artery, which communicates with the terminal aspect of the ulnar artery. The deep palmar arch is likewise a communication of the deep branches of the radial and ulnar arteries.

The strongest radial artery impulse is felt at its most superficial course on the volar aspect of the wrist (Fig. 72.1), that is, lateral to the flexor carpi radialis tendon and median nerve and medial to the superficial radial nerve and lateral radius, just before the artery descends under the extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus tendons to the anatomical snuffbox area. This usually corresponds to a site just lateral to the flexor carpi radialis tendon at the second skin crease proximal to the hand.

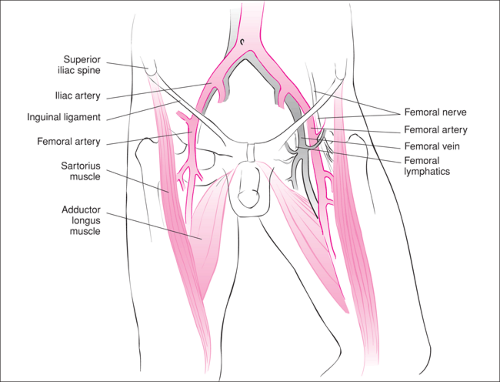

Femoral Artery

The femoral artery is a common site for arterial access in children. The femoral artery courses though the anterior thigh as a continuation of the iliac artery into the inguinal region after passing under the inguinal ligament (6). In particular, its most superficial and easily palpated course lies in the femoral triangle, bounded above by the inguinal ligament, laterally by the sartorius muscle, and medially by the adductor longus muscle. This site is most easily located as the midpoint

between the anterior superior iliac spine and the symphysis pubis (Fig. 72.2). Importantly, the operator should keep in mind the close proximity of the femoral nerve (lateral to the artery) and the femoral vein (medial to the artery). In addition, the femoral head lies posterior to the femoral triangle and can be potentially traumatized during femoral artery puncture.

between the anterior superior iliac spine and the symphysis pubis (Fig. 72.2). Importantly, the operator should keep in mind the close proximity of the femoral nerve (lateral to the artery) and the femoral vein (medial to the artery). In addition, the femoral head lies posterior to the femoral triangle and can be potentially traumatized during femoral artery puncture.

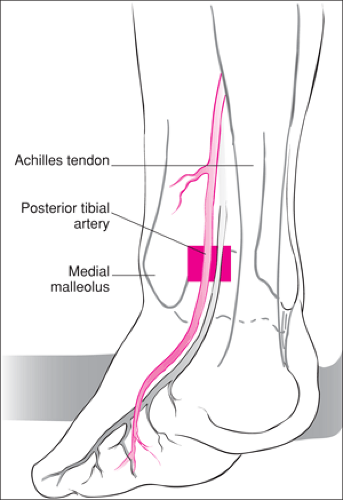

Posterior Tibial and Dorsalis Pedis Arteries

The posterior tibial artery courses the posterior aspect of the leg as the posterior branch of the popliteal artery, terminating in the plantar arteries and arch (6). Its most superficial and accessible site is a point between the medial malleolus and the calcanean (Achilles) tendon (Fig. 72.3).

The dorsalis pedis artery is a direct continuation of the anterior tibial artery, which passes down the dorsum of the foot to the proximal end of the first intermetatarsal space (6). Cannulation of the dorsalis pedis artery should be done at the dorsal midfoot, where the artery is most easily palpated; this is medial to the extensor hallucis longus and the extensor digitorum longus of the second toe (Fig. 72.4).

Axillary Artery

The subclavian artery becomes the axillary artery at the lateral border of the first rib, which in turn becomes the brachial artery at the tendon of the teres major muscle (6). It is important to locate the most superficial course of the axillary artery so as to avoid trauma to the terminal branch nerves of the brachial plexus. With the patient supine, the arm is positioned in 90-degrees abduction with the dorsum of the hand on the examination table, preferably near the ipsilateral ear or under the occiput. The axillary arterial pulse is palpated high in the axilla medial to the pectoralis major muscle insertion.

Brachial Artery

The brachial artery can be easily palpated in the antecubital fossa, where it lies atop the brachialis muscle (6). The median nerve is located along the medial side of the artery. Because there is little collateral circulation in this area, the brachial artery should not be routinely used for puncture or cannulation.

Umbilical Artery

Catheterization of the umbilical vessels in the neonate is useful and possible for hours to days after delivery. A detailed discussion of this procedure is provided in Chapter 38.

Temporal Artery

The superficial temporal artery, a terminal branch of the external carotid artery, ascends through the parotid gland, crosses the zygomatic arch, and terminates in the frontal and parietal branches (6). The course of either branch is easily palpated. The temporal artery may be a useful site for cannulation in

neonates once an umbilical artery catheter has been discontinued (3,13).

neonates once an umbilical artery catheter has been discontinued (3,13).

Indications

Analysis of pH, PO2, and PCO2 is often needed for patients with severe respiratory compromise. Although pulse oximetry (SaO2) and capnography have become important tools in the assessment of oxygenation and ventilation, arterial samples are often necessary to clarify abnormal readings or when the noninvasive technology is not available. Finally, many conditions require an accurate assessment of acid-base status for optimal management, including diabetic ketoacidosis, shock, dehydration, metabolic diseases, and certain drug and poison ingestions.

The most common indications for arterial catheterization are continuous blood pressure monitoring and serial blood sampling (1,2,3,14). Repeated arterial puncture may injure a vessel, resulting in thrombosis, infection, or an arteriovenous fistula. Serial blood pH and gas tension analysis are easily performed after arterial cannulation. Repeated blood samples can also be obtained for other indications from an indwelling arterial catheter.

Puncture or cannulation of an artery is contraindicated if compromise of arterial circulation will result. These situations are unusual but must be considered. Examples include anatomic variants and patients with artificial arteriovenous shunts. Care must be taken when performing these procedures on anticoagulated patients or those with a bleeding diathesis.

Equipment

Arterial puncture can be performed with a minimum of equipment, although prepackaged kits are available that include a needle and heparinized syringe. A 25-gauge needle should be used in the newborn, whereas a 23-gauge needle is appropriate for older infants and small children. The procedure is most easily performed with a 1-inch butterfly needle. A heparinized syringe must then be prepared by aspirating 1 mL heparinized saline (1,000 units/mL) into a syringe, coating

the barrel with the solution, and then expelling it. If too much heparin remains, the measured PCO2 may be falsely low (15).

the barrel with the solution, and then expelling it. If too much heparin remains, the measured PCO2 may be falsely low (15).

The equipment required for percutaneous arterial cannulation includes supplies to ensure aseptic technique and catheters of appropriate size and length for the age and size of the patient (Table 72.1). Equipment also is required for maintenance of the indwelling catheter and for measurement

of blood pressure. Prepackaged kits are available that include the equipment necessary for performing arterial catheterization by the catheter-over-a-wire technique (e.g., Cook Critical Care, Bloomington, IN; Arrow International, Reading, PA) (Fig. 72.5).

of blood pressure. Prepackaged kits are available that include the equipment necessary for performing arterial catheterization by the catheter-over-a-wire technique (e.g., Cook Critical Care, Bloomington, IN; Arrow International, Reading, PA) (Fig. 72.5).

TABLE 72.1 Arterial Catheter Sizes by Site and Bodyweight

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|