Introduction

Glucocorticoids are essential for life and have a wide spectrum of effects on many organ systems. Physiologically, endogenous glucocorticoid levels rise in response to a threat in homeostatic balance. In humans, the primary glucocorticoid is cortisol. The major role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is to control the synthesis and secretion of cortisol from the adrenal cortex. Glucocorticoids in turn regulate their own release through the action of a negative feedback system. The adrenal cortex secretes cortisol in a pulsatile fashion and exhibits a diurnal circadian rhythm, with cortisol levels peaking early in the morning and reaching a nadir at midnight.

Clinical administration of synthetic glucocorticoids has widespread application for a variety of medical conditions including autoimmune disease, allergic conditions, asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, and enhancement of fetal lung maturation, as in the case of threatened preterm delivery. In each case, the administration of glucocorticoids can result in both desirable (i.e. immune suppression) and undesirable effects (summarized in Table 47.1) and clinicians are well advised to always consider both the risks and benefits of their use and have a clear goal in mind when these agents are prescribed. The situation becomes even more complicated in pregnancy when clinicians must also consider all the potential risks and benefits to the embryo or fetus [1,2].

Table 47.1 Possible side effects of exogenous glucocorticoid use

| Affected system | Possible side effect |

| Behavioral | Euphoria, psychosis, depression, akathisia, insomnia |

| Blood | Leukocytosis (typically increased mature neutrophils with a mild lymphopenia) |

| Bone | Osteoporosis, avascular necrosis |

| Cardiovascular | Hypertension, premature coronary artery disease, hyperlipidemia |

| Endocrine | Hyperglycemia, secondary adrenal insufficiency from suppression of the HPA axis |

| Eye | Glaucoma, cataracts |

| Gastrointestinal | Gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, steatohepatitis, pancreatitis |

| Gynecologic | Amenorrhea |

| Immunologic | Increased risk of both typical and opportunistic infections including reactivation of herpes zoster and tuberculosis |

| Muscle | Myopathy |

| Neurologic | Pseudotumor cerebri |

| Obstetric | Intrauterine growth restriction |

| Renal | Hypokalemia, fluid retention |

| Skin and soft tissue | Skin thinning, purpura, alopecia, hypertrichosis, hirsutism, striae, moon facies, centripetal obesity and buffalo hump |

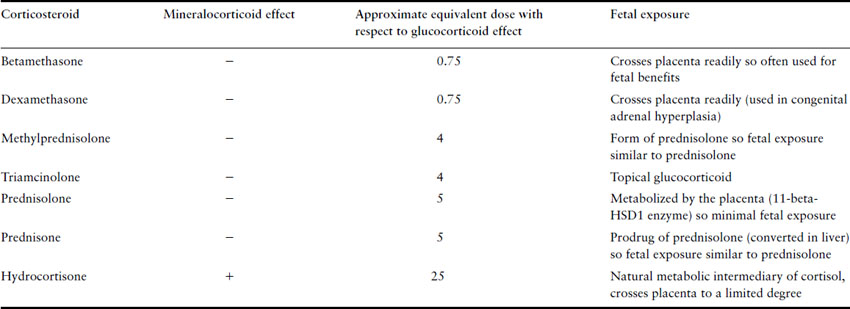

The most commonly used synthetic glucocorticoids are prednisone, methylprednisolone, triamcinolone, dexamethasone and betamethasone. Their relative potencies and degree of mineralocorticoid effect are listed in Table 47.2. Hydrocortisone is a natural metabolic intermediary of cortisol with predominantly glucocorticoid effects though it has some mineralocorticoid effects as well. Therefore, it is often used to treat patients with primary adrenal insufficiency as these patients require replacement with an agent with both effects. Prednisone, methylprednisolone, triamcinolone, dexamethasone and betamethasone were designed to have higher glucocorticoid potency, reduced mineralocorticoid effects and a longer duration of action. The latter two cross the placenta much more than prednisone and so they tend to be used in situations where it is necessary for the fetus to receive glucocorticoids (dexamethasone in reducing the incidence of female virilization in congenital adrenal hyperplasia and betamethasone in enhancing fetal lung maturation of preterm neonates). Prednisone tends to be the most common synthetic glucocorticoid used in pregnant women with chronic medical conditions as placental transfer is much less compared to the others.

Table 47.2 Approximate equivalent doses of commonly used corticosteroids

Safety of glucocorticoids in pregnancy

Systemic

The concerns surrounding the use of glucocorticoids in pregnancy began more than 50 years ago following the publication of various studies which showed that large doses of glucocorticoids administered to pregnant rabbits, mice and rats during organogenesis lead to a higher incidence of cleft palate in the exposed offspring [3–6]. This was followed by the publication of two case reports of neonates with isolated cleft palate after pregnancy exposure to cortisone [7,8]. However, several subsequent case reports in which pregnant women were treated with prednisone throughout the first trimester [9–17] for various medical conditions (including renal transplantation, Hodgkin’s disease, steroid-dependent asthma and systemic lupus ery thematosus) did not reveal a consistent pattern of embryopathy. The increased incidence of low birthweight, miscarriages and stillbirths that is noted in some studies is difficult to discriminate from the effects of the underlying maternal conditions for which the glucocorticoids were being administered.

Two large prospective cohort studies published over the past decade have shown that there is, firstly, no risk of major congenital anomalies with first-trimester use of glucocorticoids and, secondly, either only a very small (odds ratio of 3.35; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.97–5.69) [18] or no increased rate [19] of cleft lip or palate. Although the latter prospective study was only powered to detect a risk of 2.5-fold or greater, a pooling of the prospective data from these two studies describes a total of 499 pregnancies exposed to glucocorticoids with no cases of cleft lip or palate in any of the exposed offspring. It seems safe to say that glucocorticoids at therapeutic doses do not represent a major teratogenic risk in humans. Given the serious nature of the conditions treated with glucocorticoids and the fact that fetal well-being is dependent on maternal well-being, it would be difficult to envisage a situation where it would be justifiable to cease or withhold these agents during pregnancy on the basis of concerns about their teratogenic risk. This concept has made it much easier for clinicians to consider using glucocorticoids to treat a wide range of conditions, including hyperemesis gravidarum or migraines, which may be refractory to conventional treatments in early pregnancy.

Whilst systemic glucocorticoids are not significant teratogens, long-term use of the equivalent of 30 mg of prednisone per day has been shown in several studies to increase the risk of premature preterm rupture of membranes and this is consistent with the authors’ experience [20–22]. However, this again needs to be interpreted in the context of the very serious maternal and fetal implications of untreated inflammatory conditions such as asthma, systemic lupus erythematosus and inflammatory bowel disease.

Studies examining the effects of high-dose betamethasone given repeatedly to women with preterm labor do suggest an increased risk of intrauterine growth restriction [23–25] despite the marked advantage they confer to premature infants with respect to decreasing the risk of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, intraventricular hemorrhage and necrotizing enterocolitis. Concern also exists about the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of high-dose steroids on premature infants [26,27] but it should be remembered that these concerns refer to supraphysiologic doses of glucocorticoids administered with the intention of getting most of the medication to the fetus and the applicability of these data to the use of prednisone in pregnancy is doubtful. Numerous other studies, in any case, have found that there are no significant differences in neurocognitive development of infants who were exposed to antenatal high-dose glucocorticoid therapy [28–31].

Glucocorticoids can cause insulin resistance and may unmask some impaired glucose tolerance in women at risk. Consideration of early or additional screening for gestational diabetes may be warranted in women receiving glucocorticoids in pregnancy, particularly if they have additional risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus. It should be noted that betamethasone administered up to 7 days prior to a glucose challenge test or a formal glucose tolerance test may cause a spurious elevation in the result [32].

Topical

Patients and clinicians have also expressed concerns about the effects of topical steroids used on the skin, nasopharynx, airways and rectal mucosa for conditions such as eczema, aller gic rhinitis, asthma and ulcerative colitis. Systemic absorption of these agents does occur to some degree and varies with the medication, its formulation, the condition being treated, thickness of exposed skin (scalp and feet absorbing much less than the face or genitals) and whether an occlusive dressing is used. The large number of preparations available on the market also makes it difficult to develop meaningful pregnancy safety data for any one of them.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree