Introduction

Hypertension is the most common chronic medical problem encountered in pregnant women, with chronic essential hypertension estimated to complicate 1–5% of pregnancies [1]. While many women enter pregnancy with a diagnosis of chronic hypertension, others may present with elevated blood pressure (BP) for the first time in pregnancy. Hypertension that occurs remote from term, prior to 20 weeks gestation, is presumed to be chronic hypertension.

The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure provides a new classification of blood pressure for nonpregnant adults [2] (Box 42.1). A new category within this classification is that of “prehypertension” (BP 130– 139/80–89). It is estimated that individuals with blood pressure in this range are at twice the risk of developing chronic hypertension as those with normal values (BP <120/80) [3]. Furthermore, there is clear and consistent evidence that even mild hypertension is associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular disease [4,5]. The new classification of prehypertension acknowledges this relationship and emphasizes the need for better education of providers and patients in order to prevent the development of hypertension. Pregnancy offers a unique opportunity to identify women with hypertension early in the course of disease and initiate prevention strategies.

Women with severe hypertension in early pregnancy are easily identified and require close monitoring as their risk of pregnancy complications may be greater [6]. However, identification of prehypertension or stage I hypertension in pregnant women may be more difficult and requires a working knowledge of the hemodynamic changes of pregnancy. In normal pregnancy, maternal blood pressure decreases in early gestation due to a reduction in systemic vascular resistance and resistance to vasoconstricting hormones such as angiotensin II and norepinephrine. A mean decrease of 10–15 mmHg begins in the early weeks of pregnancy and reaches a nadir at 24–28 weeks. For this reason, it is very likely that a woman with prehypertension would present with normal BP values in early gestation. It is also for this reason that an elevated BP in early gestation, even if mild, should be interpreted as significant and warrants evaluation and close follow-up.

The approach to the patient with hypertension detected either prior to pregnancy or prior to 20 weeks gestation should include:

- screening for secondary or reversible causes

- evaluation for end-organ damage

- assessment of cardiovascular risk factors.

Screening for secondary causes of hypertension

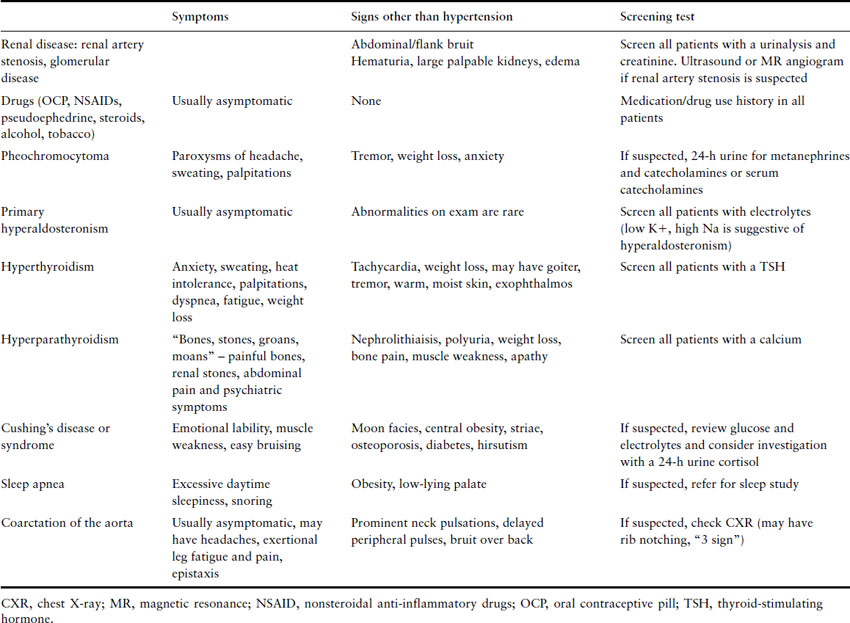

Screening for secondary or reversible causes of hypertension is an essential part of the evaluation for all newly diagnosed hypertensive patients, including pregnant women. Although only 5–10% of chronic hypertension is due to a secondary or reversible cause, many of these conditions are associated with significant complications in pregnancy if left undetected. Secondary causes of hypertension are summarized in Table 42.1.

Table 42.1 Secondary causes of hypertension

Box 42.1 Classification of hypertension in nonpregnant individuals

| Normal | <120/80 |

| Prehypertension | 120–139/85–89 |

| Hypertension: | |

| Stage I | 140–159/90–99 |

| Stage II | >160/100 |

Renal artery stenosis is the most common secondary cause of hypertension in young patients. Although less common in mild to moderate hypertension, the incidence of renal artery stenosis in patients with acute, severe or refractory hypertension is 10–45% [7]. For unclear reasons, renovascular disease is less common in black patients. Renal function and urinalysis may appear normal. The optimal screening test is a matter of much debate as even the finding of a significant stenotic lesion on imaging studies may not, ultimately, be the cause of the hypertension [8]. In pregnancy, optimal initial screening tests include ultrasound and/or magnetic resonance (MR) angiogram. Stenosis of greater than 75% in one or both renal arteries or stenosis of 50% or greater with poststenotic dilation is suggestive of renovascular hypertension. Given that no test is sufficiently accurate to completely exclude the diagnosis, correlation with clinical history is important. Clinical clues to renal artery stenosis include a history of an acute elevation of blood pressure over a previously stable baseline, severe or refractory hypertension, severe hypertension with an otherwise unexplained atrophic kidney or an acute elevation of creatinine after the initiation of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor-blocking drug. Patients with both a significant stenotic lesion and a typical clinical presentation should be referred to a nephrologist for further evaluation and treatment.

Chronic renal disease also causes hypertension and is associated with an increased risk of pregnancy complications [9]. Patients with early-stage disease may have no significant signs or symptoms on history and physical examination, but will generally have an abnormal urinalysis and/or creatinine.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree