Anatomic Disorders of the Esophagus

Dave R. Lal

Congenital atresia of the esophagus and tracheoesophageal fistula occur in 1 of every 2500 to 3000 live births. Other congenital disorders of the esophagus, such as esophageal webs, strictures, duplications, and extrinsic vascular rings are far less common. Acquired esophageal lesions include strictures due to caustic injury, gastroesophageal reflux or eosinophilic esophagitis, and, rarely, diverticula.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND GENETICS OF CONGENITAL ESOPHAGEAL MALFORMATIONS

The embryologic mechanisms responsible for both normal and abnormal trachea and esophageal development are not fully elucidated. At day 26 or 27 of gestation, a ventral diverticulum is formed from the caudal end of the primitive pharyngeal foregut. This laryngotracheal diverticulum undergoes elongation and differentiation to eventually form the larynx, trachea, bronchi, and lungs. In order to separate the dorsal foregut (future esophagus) from the ventral laryngotracheal diverticulum, longitudinal tracheoesophageal folds fuse to form a septum that completely separates these structures (eFig. 392.1  ). It is believed that failure of these folds to completely form, or improper timing of their formation, leads to the anomalies of esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF).

). It is believed that failure of these folds to completely form, or improper timing of their formation, leads to the anomalies of esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF).

The genetic factors that lead to malformation of the trachea and esophagus have not yet been elucidated. There is a small increased risk of TEF of about 2% if there is an affected sibling. There are associated anomalies, with cardiac malformations being the most common, in about half of the cases of esophageal atresia (syndromatic esophageal atresia). In the remainder (nonsyndromic cases), esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula occur in isolation. The specific genes and signaling pathways that lead to esophageal malformations are yet to be determined.1

ESOPHAGEAL ATRESIA

CLINICAL FEATURES AND CLASSIFICATION

CLINICAL FEATURES AND CLASSIFICATION

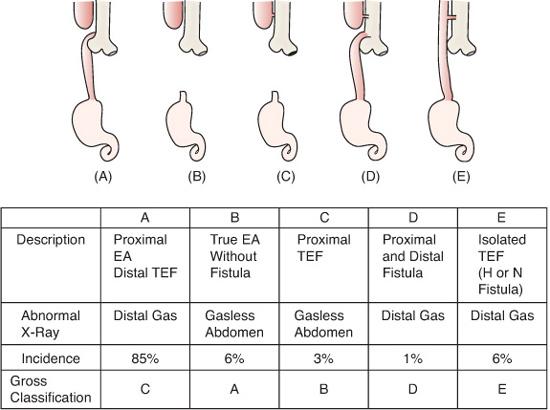

Esophageal atresia (EA) has been classified into 5 types based on whether the esophagus is present and the location of fistula to the trachea. Figure 392-1 illustrates the different types of atresias with their incidence and anatomic findings. The most common type of EA has atresia of the esophagus with a distal tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) (85%) with an esophageal fistula that typically originates just proximal to the carina in the posterior trachea. The next most common is a pure esophageal atresia without TEF (10%). The blind-ending upper esophageal pouch can have a variable length that determines if primary repair is feasible.

Tracheoesophageal fistula is associated with several other congenital anomalies.5 The most common association is described by the acronym VACTERL and includes anomalies of the vertebrae (similar to those of spondylocostal dysplasia), intestinal atresia, cardiac malformations (patent ductus arteriosus, atrial septal defect, or ventricular septal defect), tracheoesophageal fistula, renal anomalies (urethral atresia with hydronephrosis), and limb anomalies (hexadactyly, humeral hypoplasia, radial aplasia, and proximally placed thumb) (see Table 415-2). Rare cases of VACTERL association in the offspring of an affected individual have been reported, but this is uncommon. eTable 392.1  shows the incidence of anomalies in a large series of patients with esophageal atresia.5 Other associated anomalies include hypospadias, undescended testis, duodenal atresia (as in oculodigitalesophagoduodenal syndrome with gene defect in the 2p24–p23 region), and hydrocephalus secondary to aqueductal stenosis. Genetic syndromes, including oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia (Goldenhar syndrome) and Opitz-G syndrome, can also be associated with esophageal anomalies.

shows the incidence of anomalies in a large series of patients with esophageal atresia.5 Other associated anomalies include hypospadias, undescended testis, duodenal atresia (as in oculodigitalesophagoduodenal syndrome with gene defect in the 2p24–p23 region), and hydrocephalus secondary to aqueductal stenosis. Genetic syndromes, including oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia (Goldenhar syndrome) and Opitz-G syndrome, can also be associated with esophageal anomalies.

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

Polyhydramnios is present in about one third of mothers carrying infants with esophageal fistula with distal tracheoesophageal fistula and in virtually 100% of mothers carrying infants with pure esophageal atresia, apparently due to the inability of the fetus to swallow amniotic fluid. Other antenatal ultrasound findings often include microgastria or a distended upper esophageal pouch.

FIGURE 392-1. Various types of esophageal atresia along with their incidence (%), anatomic findings and Gross/Vogt classifications. A: Esophageal atresia with distal tracheoesophageal fistula. B: Esophageal atresia alone. C: Esophageal atresia with proximal tracheoesophageal fistula. D: Esophageal atresia with double fistula. E: Isolated tracheoesophageal fistula. EA, esophageal atresia; TEF, tracheoesophageal fistula. (Source: Beasley SW. Esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. In: Oldham KT, Colombani PM, Foglia RP, et al, eds. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:1040.)

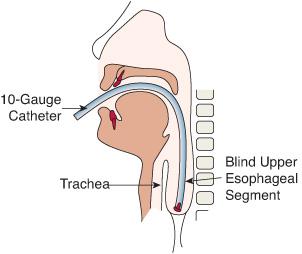

After birth, the presence of excessive drooling or aspiration and coughing with feeds should lead to an evaluation for esophageal atresia. Confirmation of the diagnosis can be made by attempting to gently pass a 10 French orogastric tube into the stomach. If esophageal atresia is present, a radiograph can be taken while mild pressure is placed on the tube to determine the approximate length of the proximal esophageal pouch. Rib spaces or vertebrae can be counted between the tip of the orogastric tube and the carina to determine the length of the esophageal gap (Fig. 392-2). The site of the carina on chest x-ray can serve as a surrogate for the location of the distal esophageal segment. The chest radiograph also diagnoses a fistula if air is seen in the intestines. This can be in the form of a distal, isolated, or double fistula. Conversely, if the infant has a gasless abdomen, then the diagnosis is true esophageal atresia or a proximal tracheoesophageal fistula. Contrast studies should be avoided due to the risk of aspiration.

In contrast to this typical presentation, patients with H-type fistulas (intact esophagus with a congenital tracheoesophageal fistula) typically present later in life, with repeated bouts of aspiration pneumonia. Because their esophagus is in continuity, they are able to eat; however, they aspirate swallowed or refluxed esophageal contents via the fistula. The diagnosis can be difficult; routine radiographic barium swallows often overlook the fistula. The fistula is best identified by instilling thin barium through the tip of a nasogastric tube, with moderate pressure to distend the esophagus while slowly withdrawing the tube from the stomach into the esophagus. This tends to force the fistula open and allows visualization, as seen in eFigure 392.2A  . Repeated radiography and/or rigid esophagoscopy and bronchoscopy may be necessary before the diagnosis is recognized (eFig. 392.2B

. Repeated radiography and/or rigid esophagoscopy and bronchoscopy may be necessary before the diagnosis is recognized (eFig. 392.2B  ).

).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree