FIGURE 36-1 Clinical photograph of sharp amputations of the index and long fingers. The level of amputation is through the proximal phalanx, and the wound is relatively clean. Given the quality of the amputated parts, these digits would be deemed good candidates for replantation.

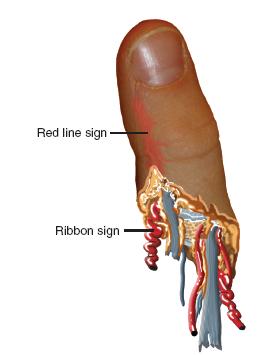

FIGURE 36-2 Schematic diagram of the amputated digit, exhibiting the ribbon and red-line signs suggestive of avulsion mechanisms.

Radiographs should be obtained of the affected hand and upper limb, in addition to all available amputated part(s). Assessment of the skeletal injuries will allow for proper preoperative planning and provide further information regarding the zone and energy of injury.

The proper care of the amputated part during transport and prior to replantation is well established. The amputated digit should be wrapped in moist, salinesoaked gauze and placed in a plastic bag. The entire bag is then placed in a container on an ice bath and transported with the patient.5–7 Every effort should be made to save all identifiable parts, as “spare parts” may be used orthotopically during surgical reconstruction. In general, for digital amputations, up to 12 hours of warm ischemia and 24 hours of cold ischemia can be accepted prior to replantation.7 For more proximal amputation—in which there is more muscle tissue—6 hours of warm and 12 hours of cold ischemia are considered acceptable for successful replantation.

Surgical Indications

General indications for replantation in adults include thumb amputations, multiple-digit amputations, amputations through the wrist or proximal, as well as single-digit amputations distal to the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) insertion.8 However, replantation of any amputated part is almost always attempted in a child.

Contraindications to replantation include severely crushed, mangled, or contaminated parts, particularly with segmental injury; amputations in patients with significant medical comorbidities or inability to comply with postoperative restrictions and rehabilitation; and amputations with excessive warm ischemia time.

While these indications are generally well accepted, it is imperative that a frank discussion be had with the patient and/or family regarding the surgical options, treatment priorities, and expected outcomes. Successful replantation, defined as tissue viability, does not always equate with full functional restoration. Furthermore, each patient and family is accompanied by their own set of personal and cultural biases; reconciling the hopes and desires of the family with the realistic expectations of surgical treatment is an important ongoing process that begins at the time of presentation.9

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Great things are done when men and mountains meet.

—William Blake

The treatment principles for the management of digital or upper limb amputations are intuitive. Generally speaking, attention to the amputated part should not detract from care of the overall patient, particularly in multitrauma or more involved injuries. Life comes before limb, and every effort is made to avoid infection, particularly in the severely traumatized extremity. Replantation procedures should not burn bridges to future reconstructive efforts, and heroic, complex operations should not be performed for patients or families unwilling or unable to participate in the postoperative recovery.

Surgically, replantation proceeds through a sequence of established steps: (1) identification of vessels and nerves, which may be tagged with marking sutures for later repair; (2) thorough irrigation and debridement; (3) skeletal fixation with judicious bony shortening; (4) extensor tendon repair; (5) flexor tendon repair; (6) arterial anastomosis with or without interpositional vein grafting; (7) nerve repair; (8) venous anastomosis with or without interpositional grafting; and (9) loose skin closure. While there are variations in technique, and each patient presents different challenges, the fundamental steps are the same.

Replant of Sharp Amputation with Direct Repair

Replant of Sharp Amputation with Direct Repair

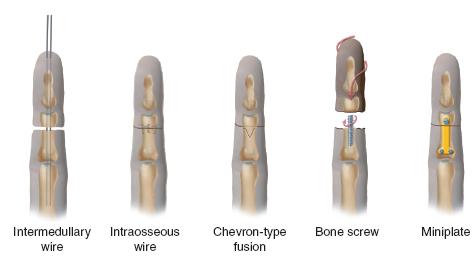

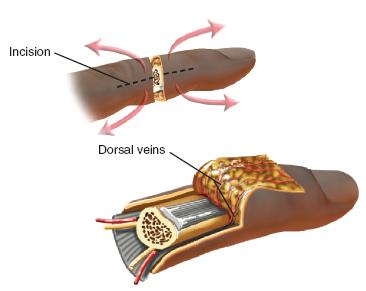

Sharp traumatic amputation represents one of the most favorable situations for digital replantation.10–14 Surgery begins even prior to the patient entering the operating room. Whenever possible, the amputated part is transported to the operating theater while the patient is being evaluated in the emergency department. The part is first cleaned with chlorhexidine, betadine, and/or sterile saline solution, and all foreign material is debrided. Under loupe and microscopic visualization, midaxial incisions are created radially and ulnarly (Figure 36-3). Skin flaps are carefully raised. Volarly each digital artery and nerve is atraumatically identified and circumferentially dissected using microsurgical instruments. Vessel clamps or fine sutures (our preference is to use a blue 6-0 polypropylene suture [Prolene, Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ]) may be used to tag the very ends of the vessels and nerves for later identification. The distal flexor tendon may similarly be identified and a core suture placed for subsequent tenorrhaphy. Dorsal dissection is more delicate, particularly, as the veins of the avascular segment are collapsed and prone to further injury. The dorsal skin flap is raised, and the plane of dissection is performed between the subdermal and deep fatty layers, where the dorsal veins are identified. These may be similarly clipped or tagged for later use. The extensor tendon stump is also identified, and sutures may be placed. Direction is then turned to the bone. With the use of a microsagittal saw or sharp bone cutter, judicious shortening of a few millimeters is performed, with care taken not to crush the phalanx or injure the adjacent soft tissues.15,16 Smooth K-wires are then placed in a retrograde fashion (longitudinally or obliquely) in preparation for subsequent fixation to the hand. While plates and screws or interosseous wiring may also be used and have mechanical strength advantages, we find that K-wires are simple, faster, efficacious, and do not add bulk or tension to the surrounding soft tissues.16–22 Once the soft tissue preparation, bony shortening, and skeletal fixation have been performed, the amputated part is placed in moist gauze on sterile ice to maintain cold ischemia until ready for replantation.

FIGURE 36-3 Midaxial incisions utilized for preparation and exposure of the vessels, nerves, tendons, and bone during replantation.

The patient is simultaneously brought to the operating room and anesthetized. Adequate intravenous access is obtained, a urinary catheter placed, and the ipsilateral upper extremity prepped and draped into the surgical field. In cases of proximal replantation or extensive zones of injury, the ipsilateral lower limb is also prepped and draped into the field in the event that vein graft from the leg needs to be harvested.

The amputation site is similarly exposed using midaxial incisions. The digital arteries, nerves, veins, and flexor and extensor tendons are identified and mobilized. Core sutures may again be placed in the flexor tendon to facilitate repair later and prevent recurrent retraction into the more proximal tendon sheath or palm. Thorough irrigation and debridement is performed, removing all nonviable tissue and foreign material. Skeletal shortening of the proximal bone may be performed in a fashion that will appropriately engage the amputated part; in general, transverse shortening is the easiest and most reliably performed.

Bony fixation is then performed, reapproximating the amputated part to the prepared recipient site. The previously placed K-wires are passed into the more proximal bone, and longitudinal alignment and rotational position secured (Figure 36-4). Flexor and extensor tenorrhaphies are then performed in the standard fashion23 (see Chapter 38).

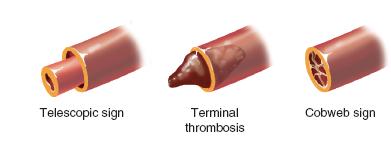

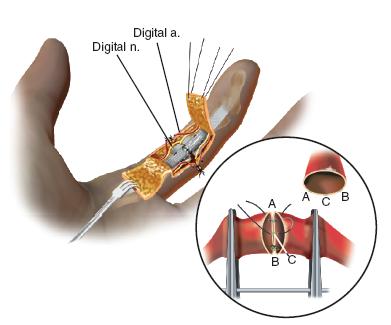

Attention is then turned to reestablishing arterial inflo w. Under microscopic visualization, the proximal arterial stump is evaluated. It is common to see a clot occluding the lumen and varying degrees of adventitial and intimal damage at the site of amputation (Figure 36-5). It is critical for the artery to be trimmed back to a normal, healthy vessel. When this is performed, there will be a brisk, pulsatile flow, which should spurt bright red blood across the surgical field. Once the proximal arterial flow is established, the lumen of the artery is dilated using a microvascular dilator. A smooth vascular clamp mounted on a microsurgical sliding stage is then placed, leaving adequate distal stump exposed for anastomosis. The corresponding distal arterial stump on the amputated part is similarly trimmed back to normal-appearing tissue. Heparinized saline is infiltrated through the amputated artery, and the vessel wall dilated. The second smooth vascular clamp mounted on the stage is then used to stabilize the distal artery. With confirmation that there is no undue tension and the vessels may be easily reapproximated, microvascular anastomosis is performed, usually with 10-0 simple interrupted nylon sutures. The back wall is reapproximated first, after which the vessel is rotated 180 degrees and the front wall completed (Figure 36-6). Upon completion of the arterial anastomosis, the vessel clamps are released, and confirmation of arterial inflow is made. Additional sutures may be placed if needed. The arterial anastomosis is then covered with the adjacent subcutaneous skin and fat flap. The distal fingertip is observed for restoration of turgor and color.

FIGURE 36-5 Schematic diagram depicting signs of vascular damage requiring additional trimming prior to vascular anastomosis.

FIGURE 36-6 Technique of microvascular repair.

A number of maneuvers may be used to optimize vascular patency and flow. First, just prior to vascular anastomosis, our preference is to initiate a continuous infusion of dextran 40 at 5 to 10 ml/kg/day. While others have used intravenous heparin, we have found that volume expansion using dextran provides sufficient anticoagulation effect without the risks of fluid overload and cardiac failure seen in adults. Secondly, the ambient room temperature is raised as high as the patient and surgical team can tolerate. Maintenance of appropriate body core temperature is important to avoid peripheral vasoconstriction. Furthermore, topical administration of 10% lidocaine or papaverine (1:20 concentration) to the vessels will also promote vasodilation. Finally, arterial flow needs time to be reestablished. The surgeon and surgical team should be patient before rushing to revise or explore an arterial anastomosis. We wait at least 10 minutes before uncovering the arterial repair. In general, reconstituting a single digital artery is sufficient and is what we perform. If in doubt about the quality of the inflow, repair both arteries.

After inflow is reestablished and while the volar aspect of the hand is exposed, neurorrhaphy is performed of each digital nerve in the standard fashion.24 Epineurial 9-0 nylon sutures are typically sufficient.

The hand is then flipped and the dorsal aspect exposed. Attention is turned to venous anastomosis. The advantage of anastomosing the veins last is that arterial inflow will serve to backfill the veins on the amputated part, making their identification and manipulation easier. The disadvantage of a “vein last” approach is that the surgical field is often bloody at this stage, providing challenges in visualization. Steps that can be taken to improve visualization include frequent atraumatic blotting or suction, frequent irrigation with heparinized saline or papaverine solution, or temporary use of a pneumatic tourniquet placed in the upper brachium. Venous anastomosis is performed under microscopic visualization, again using 9-0 or 10-0 simple interrupted nylon sutures. Reconstitution of two veins is preferred.25,26

At the conclusion of the case, skin flaps are reapproximated and closed loosely with interrupted 4-0 or 5-0 sutures (Chromic, Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ). Care is taken not to make the skin closure too tight for fear of constricting the vascular anastomoses; better to leave the wound a little too open than cause interruption of inflow or outflow. This is yet another advantage of the midaxial approach.

Postoperatively, loose bulky dressing is applied, followed by volar splint or cast immobilization. Care is taken to be certain that there is no external constriction.

Replant of Crush or Avulsion Amputation with Grafts

Replant of Crush or Avulsion Amputation with Grafts

Crush and/or avulsion injuries impart a greater zone of injury. While the principles and surgical steps are the same as in clean, guillotine amputations, often there is wider, more extensive injury to the digital arteries and veins. Even with bony shortening, primary end-to-end anastomoses of healthy vessels may not be possible. In these situations, early recognition and prompt conversion to interpositional vein grafting will be both time saving and more effective in achieving the surgical goals.27,28

There are a plethora of suitable donor veins for grafting. In digital injuries where the proximal upper limb is not traumatized, the volar wrist and distal forearm veins are abundant, easily accessible, and the appropriate caliber for interpositional grafting. It is helpful to mark these veins out with a marking pen even prior to beginning a replantation procedure. Via a longitudinal skin incision of the distal forearm, these veins may be identified and harvested. Vascular clips are placed an appropriate distance apart, and the vein is taken. Heparinized saline or papaverine solution is injected into the vein to flush out potentially thrombogenic blood and dilate the vessel wall. A tagging suture or additional vascular clip can be applied to mark the polarity of the vein. (Our preference is to reverse the vein graft in the event that the graft includes any valves that may impede subsequent blood flow.) The vein is then placed into a solution of papaverine until needed.

The microvascular anastomosis from native vessel-to-vein graft is performed using standard techniques (Figure 36-7). Often, these repairs are easier, due to the length and therefore lack of tension of the interpositional graft. Indeed, in multiple digit or thumb avulsions, vein grafts may be plugged end to side into the palmar arch or deep dorsal branch of the radial artery, respectively, if needed.

FIGURE 36-7 Intraoperative photograph following replantation of a right ring avulsion injury; due to the extensive zone of injury, an interpositional vein graft (arrow) was needed to restore arterial inflow.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree