Fig. 7.1

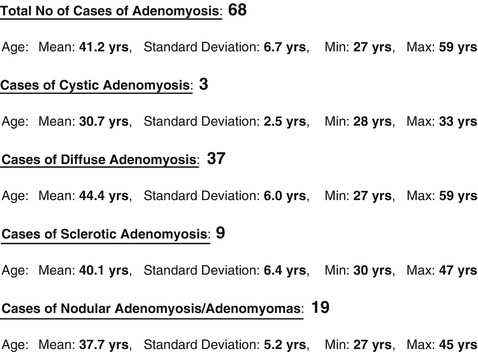

Uterine adenomyosis: breakdown according to type (total 68 patients)

Group A. Diffuse adenomyosis (Fig. 7.2)

Fig. 7.2

Laparoscopic image of diffuse posterior adenomyosis

mean age: 44.4 years (range 27–59)

presenting symptoms: menorrhagia, dysmenorrhoea

imaging: uniformly enlarge uterus, most frequently posterior area, commonly seen myometrial inclusion cysts

topography: uniformly enlarged uterus

intra-operative findings: spongiform enlarged uterus, myomata and deep endometriosis also found between 11 and 36 % of cases.

Group B. Nodular adenomyosis (Fig. 7.3)

Fig. 7.3

Nodular adenomyosis close to left round ligament

mean age: 37.7 (range 27–45),

presenting symptoms: cyclic pain-dysmenorrhea disproportionate for the size of the lesion, resemble deep endometriotic nodules

imaging: spherical lesion resembling small myoma

topography: fundal – apical area near the round ligaments or the tubal isthmus,

intra-operative findings: firmly attached to serosa, no pseudo-capsule.

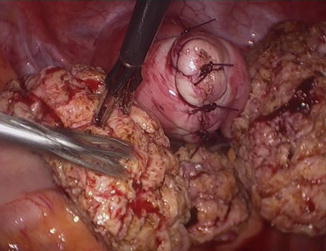

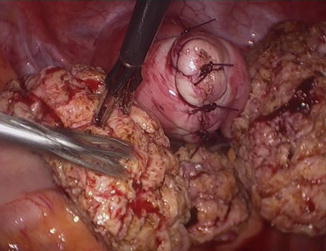

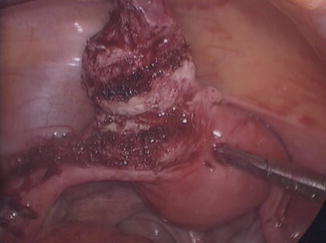

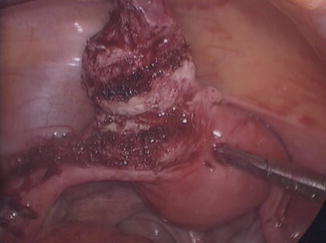

Group C. Sclerotic adenomyosis (Fig. 7.4)

Fig. 7.4

Large posterior sclerotic adenomyoma

mean age: 40.1 (range 30–47)

presenting symptoms: dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia and subfertility

imaging: ill defined, irregularly shaped intra-mural mass, occasionally inclusion cysts, lacking the characteristic appearance of the myomatous pseudo-capsule.

topography: intra-mural lesion more often posterior uterine wall. Macroscopically resembles myoma

intra-operative findings: During excision the lesion has sclerotic whitish appearance, friable and difficult to grasp. Reduced bleeding, the lesion firmly attached to the serosa and to the endometrium

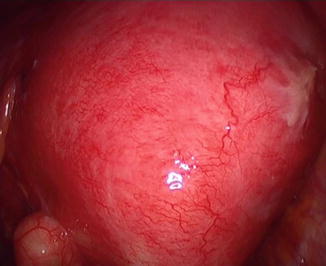

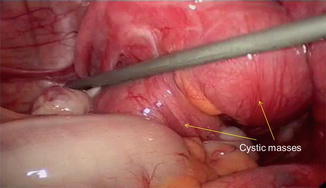

Group D. Cystic adenomyosis (Fig. 7.5)

Fig. 7.5

Cystic adenomyosis

mean age: 30.7 (range 28–33)

presenting symptoms: dysmenorrhea

imaging: large (>3 cm) intramural endometriotic looking cyst

topography: random intramural distribution. Primary cystic lesion (type II) of the adult needs to be distinguished from secondary iatrogenic lesion or the rarer form of juvenile cystic adenomyosis (type I) [27]

intra-operative findings: typical endometriotic like cyst, firmly adherent on surrounding myometrium

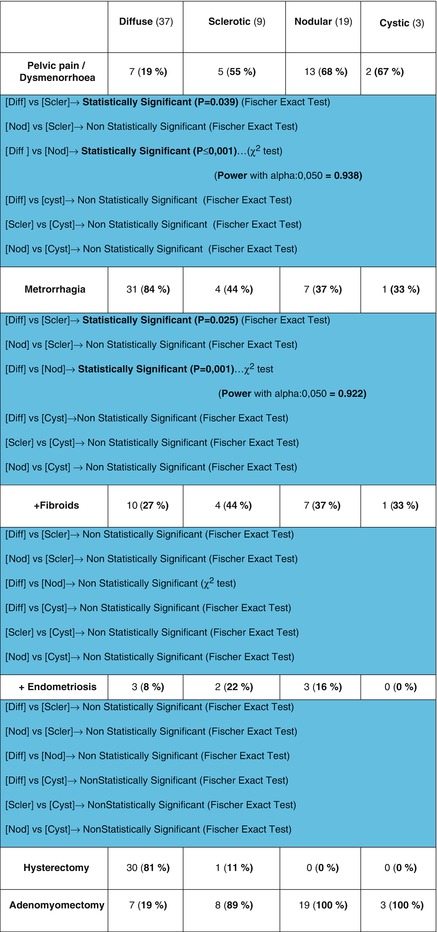

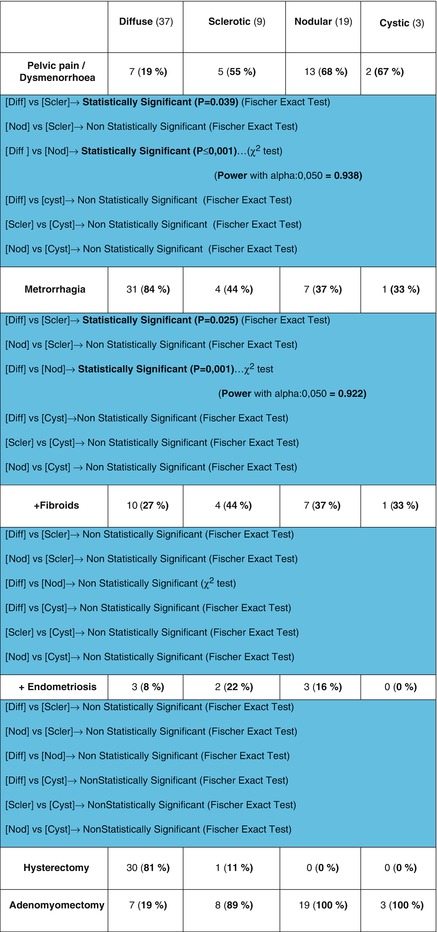

Symptomatology and Adenomyosis Types

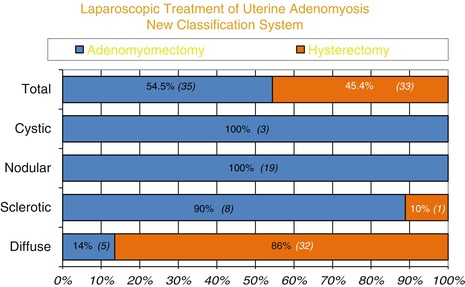

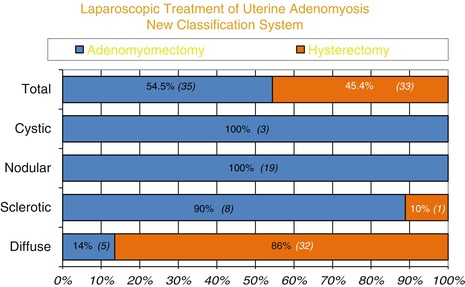

There seemed to be significantly more patients with sclerotic (p = 0.039) and nodular type (p ≤ 0.001) lesions complaining of severe dysmenorrhea compared with diffused adenomyosis. Although two out of the three patients with cystic lesions also suffered with pelvic pain, the difference with the other types of adenomyosis was not statistically significant possibly due to small number of patients with cystic lesions (Fig. 7.6).

Fig. 7.6

Hysterectomy vs adeno-myomectomy: surgical outcome of the four adenomyosis type

Adenomyosis Types and Endometriosis and Fibroids

Fibroids and endometriosis occurred in a variable proportion with all types of adenomyosis. Myomas seemed to co-exist in 10 (27 %) with diffused, 4 (44 %) with sclerotic, 7 (37 %) with nodular and 1 (33 %) with cystic adenomyosis. Endometriosis occurred in 3 (8 %) of diffused lesions, 2 (22 %) sclerotic lesions, 3 (16 %) nodular lesions and 0 % in cystic lesions. in both fibroids and endometriosis cases there was not statistical significance between the four groups of adenomyosis lesions (Fig. 7.7).

Fig. 7.7

Table with statistics used to compare adenomyosis types and symptomatology

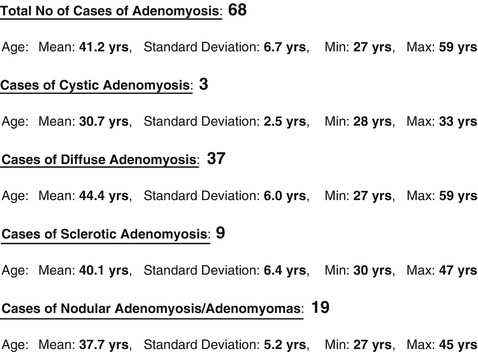

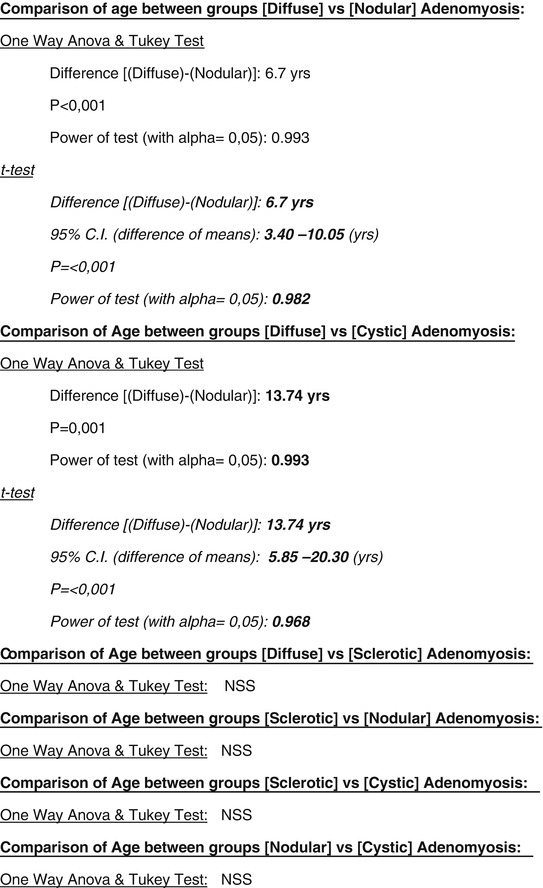

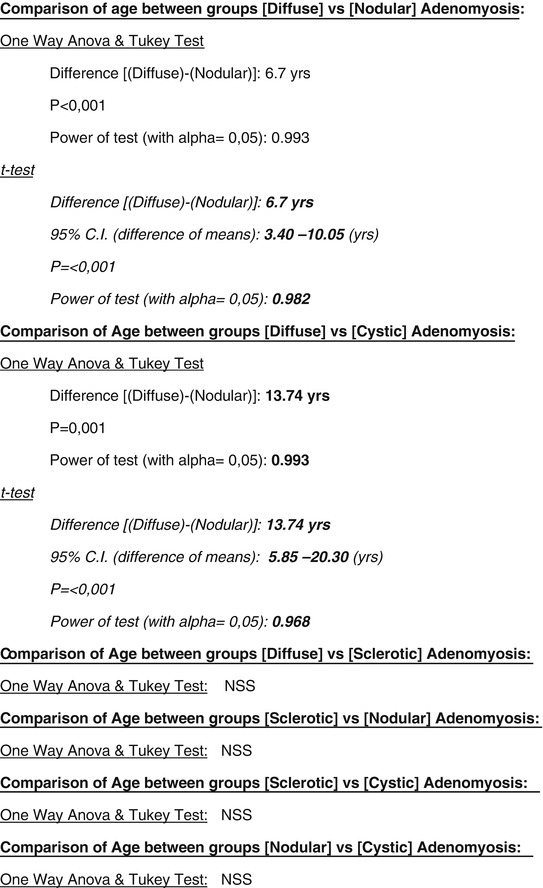

Age and Adenomyosis Types

There seemed to be an age distribution of adeomyosis types with cystic lesions occurring in youngest age group, mean 30.7 years, nodular lesions, mean age 37.7, sclerotic lesions mean age 40.1 and diffuse mean age 44.4 (Fig. 7.8). Significant statistical difference was observed in the age onset between diffuse and nodular lesions p ≤ 0.001 and diffuse and cystic lesions p ≤ 0.001 (Fig. 7.9).

Fig. 7.8

Table of adenomyosis types and age groups

Fig. 7.9

Comparison of adenomyosis age groups, statistical methods and result

Therapy for the Four Different Types of Adenomyosis

Laparoscopic techniques for adenomyotic lesions

Diffuse Adenomyosis

When uterine preservation is required, this type of surgery presents an enormous challenge. Technically, a partial uterine resection has to be performed and this anatomically is a debilitating procedure. Most often what remains is a reduced organ with ambiguous functional capacity as regards fertility. This type of surgery is in reality a method of complete uterine reconstruction and patients should be warned about risks. Not only the resulting uterus has reduced reproductive capacity but the organ could rupture in a subsequent pregnancy! [28] Additionally, one needs to be prepared to face severe adhesions since a significant proportion of such patients have had previous surgery. The operative technique entails removing most of the affected myometrium and suturing together healthy tissue. It is of paramount importance that the pre-operative assessment of the lesion is conducted by the surgeon himself. In most cases the lesion cannot be removed en bloc and should be resected in a stepwise fashion, often having to “tunnel” under the uterine serosa in order to preserve as much uterine surface as possible. We inject the operative area with vasopressin and use mono-polar current to cut the tissue. Once the whitish fibrotic tissue is removed pinker and better blood supplied myometrium is found. It is vital to suture healthy tissue to healthy tissue and not to adenomyotic because the latter leads to defective healing. We have coined the acronym C.U.R.E.S., i.e. C omplete U terine R econstructive E ndoscopic S urgery when we refer to this type of massive adenomyosis resection (Fig. 7.10).

Fig. 7.10

C.U.R.E.S. Resection of posterior diffused adenomyosis with uterine repair. Most of the posterior fundal area is resected

The massive uterine wounds that ensue from such resections have to be repaired in layers. We use long 40 mm atraumatic needles for the deep layers which we repair with 1 monocril sutures and 0–2.0 monocril for the serosal closure.

In our series, in only 5 (13.5 %) patients with diffuse adenomyosis was uterine sparing surgery possible in contrast with 7 (77.8 %) of women with sclerotic lesions. In the remaining cases total or subtotal hysterectomy was performed. The strongest indication for total hysterectomy is the presence of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) affecting the cervix and recto vaginal septum (RVS). This is not an uncommon situation in cases of diffuse adenomyosis. If endometriotic nodules remain after surgery, dysmenorrhea will most likely persist! The use of anti-adhesive measures is currently being assessed in our centre but no substance has so far proven to be of significance in adhesion prevention.

Nodular Adenomyosis

This occurs more frequently in younger women who typically present with disproportionate dysmenorrhea for the type and size of their pathology. Nodular lesions are frequently located in the apical – fundal part of the uterus and are painful on palpation. During surgery these nodules are tenaciously adherent, like all adenomyomata, to the surrounding tissues. When they’re removed they leave a noticeable defect on the uterine wall which is frequently located near the tubal isthmus (Fig. 7.11). Repair is not easy since tubal patency is mandatory and the wound edges are in close proximity to such structures. Vasopressin is also valuable in such cases because anastomotic vessels are often involved in such lesions.

Fig. 7.11

Nodular lesion removed from left uterine horn

Repair is ideally performed in two layers with 3.0 or 2.0 monocryl sutures in two layers with interrupted sutures. Subsequent pregnancies need careful follow-up. Symptoms of dysmenorrhea disappear soon after surgery. From our limited experience, it was surprising to note that women with nodular endometriosis did not have concomitant Deep Infiltrating Endometriosis (DIE) of the Recto Vaginal Septum (RVS).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree