Acute Fever without a Focus

Steven Black

Fever is defined as a regulated rise in core body temperature. That is, as distinct from hyper-thermia, it is a measured response to internal regulatory processes. Most clinicians define fever as a rectal temperature of 38°C (101.4°F) or higher. Fever is the most common cause for sick child visits to the pediatrician and emergency room. Fever is part of the body’s response to many adverse stimuli, including inflammation, infection, and malignancy, among other causes. In the pediatric age group, infection due to a virus or bacteria is the most common cause of fever. The tendency to seek medical attention for fever is very much age dependent, with younger children seeking care most often. Although part of the tendency to seek medical attention for fever rests with parental anxiety, part rests appropriately with the increased risk of serious infection associated with fever in the youngest children, neonates, as well as in special risk groups.

The physiology of temperature regulation is detailed in Chapter 121 and further information on the management of the febrile child can be found in Chapter 105.

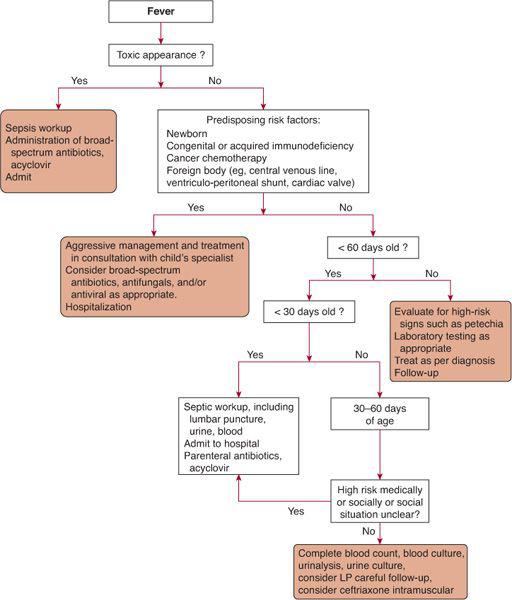

Fever is not a diagnosis per se. Often the pediatrician’s first goal is to separate serious causes of fever from minor self-limited intercurrent illnesses. The most useful tool in the diagnosis of the etiology of fever is the clinical examination. Many months of residency and years in clinical practice hone the pediatrician’s ability to identify the truly sick or “toxic” child. Perhaps no clinical skill is more important for a pediatrician, who is often dealing with young children who are not able to communicate directly, than the ability to identify the seriously ill child. Listlessness, poor feeding, poor perfusion of the extremities, weakness, rapid pulse, or lethargy are all clues, as are the more sinister presence of cyanosis or purpura. Often the signs are subtle and the child just does “not look right.” Once the child is identified as being toxic or seriously ill, then appropriate cultures, most often including urine, blood, and CSF, as well as other laboratory tests such as a peripheral white blood cell (WBC) count with differential, electrolytes, and urinalysis, should be obtained. Some clinicians also use C-reactive protein (CRP) or procalcitonin testing to evaluate febrile children because these are selectively elevated in children with bacterial infection.5 For the truly toxic child and especially for younger children, age-appropriate antibiotics that can treat sepsis and possible meningitis should be started. In most areas of the country, this must now include coverage against resistant gram-positive organisms through the inclusion of vancomycin. For the child that is less seriously ill, a more measured clinical evaluation is warranted. Such an evaluation should include history as well a physical examination to delineate the patient’s symptoms and clinical course. Knowledge of the most common infectious etiologies in a given age group is also important. Pharyngitis, upper respiratory infection, otitis media, gastroenteritis, and bronchiolitis are all common causes of fever and can often be diagnosed by review of the history and physical examination alone. Similarly, varicella, roseola, and scarlet fever, as well as Kawasaki disease, can also be diagnosed on the basis of physical examination. For other entities, it may not be possible to identify a specific focus of infection. For children without a readily identifiable focus, the most common etiology is a self-limited viral illness. Two common causes of fever in infants and children are urinary tract infection and occult bacteremia. Urinary tract infection is discussed further in Chapter 238. Prolonged fever of unknown origin is discussed in Chapter 228, and fever in the immunocompromised child is discussed in Chapter 229. Occult bacteremia is discussed below. An algorithm summarizing the evaluation and management of febrile infants and children is shown in Figure 227-1.

Fever patterns can occasionally be useful in the diagnosis of specific conditions such as malaria. In most situations, these patterns tend to be nonspecific. Similarly, dissociation between the pulse rate and the peak of temperature (high temperature, lower pulse than normally expected) can be seen in typhoid fever and brucellosis, but not in all cases. Neoplasia is also often associated with fever, especially in the case of leukemia and lymphoma. Other noninfectious causes of fever include drug fever, hyperthyroidism, adrenal insufficiency, and autoimmune disorders such as lupus and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Rarely, factitious fever can be seen in the young child. However, the most common cause of acute fever in children is infection, with most children having experienced at least one such febrile episode in the first year of life.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree