The Resuscitation of the Newborn With a Difficult Airway

INTRODUCTION

Successful resuscitation of the newborn nearly always begins with the establishment of a patent airway through which gas exchange will occur. However, the neonatal airway may be compromised by a number of developmental anomalies that make resuscitation challenging. Some of these anomalies are relatively benign and respond to simple maneuvers to achieve an airway. On the other end of the spectrum are other anomalies that may be lethal despite prenatal diagnosis and delivery at a center with advanced airway management capability. In either case, delivery room management will be influenced by the severity of the anomaly and the resulting degree of airway obstruction. Appropriate interventions in the delivery room may range from the placement of an ancillary device to maintain patency of the airway to the coordinated, multidisciplinary surgical intervention while the infant continues to be supported by the placental circulation. This chapter reviews the differential diagnosis of newborn airway obstruction and describes the overall approach to delivery room management of airway anomalies that range from mild to severe.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

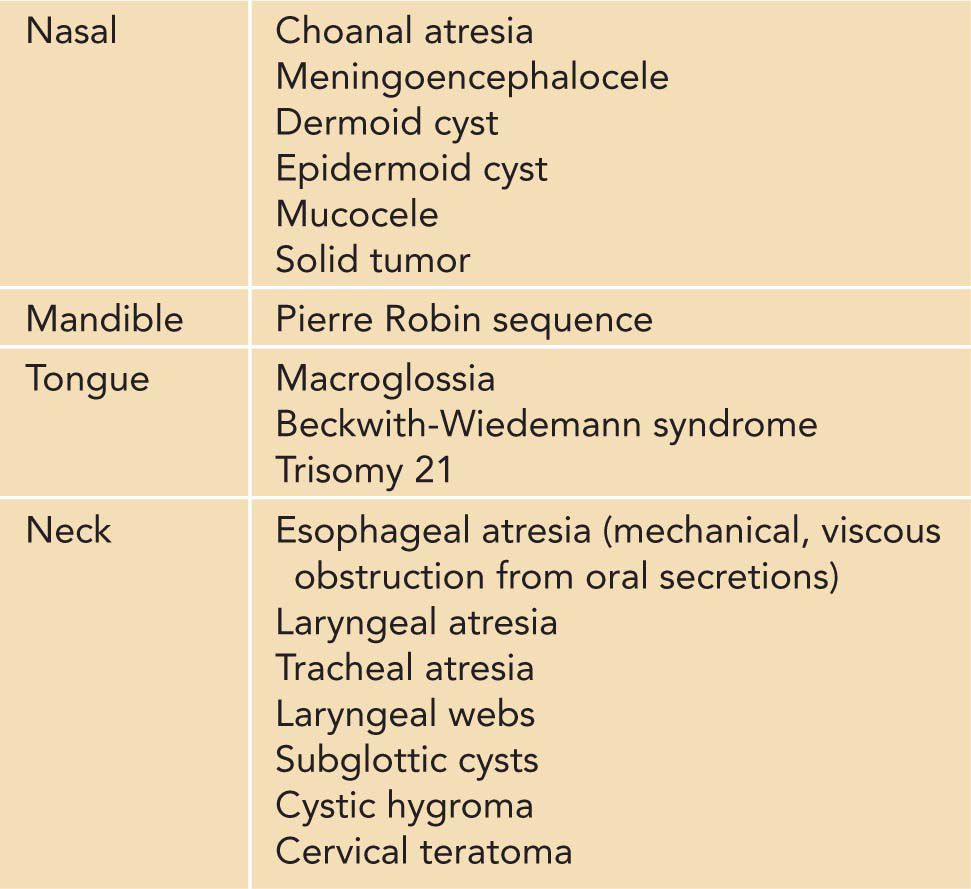

Obstruction of the neonatal airway may occur at many different levels. Choanal atresia is an upper airway anomaly that may cause respiratory distress immediately after birth or on initiation of early feeding attempts.1 Choanal atresia most often is caused by bony obstruction and may affect either 1 or both sides of the nasal passages.2 Choanal atresia may be isolated or a component of CHARGE association (coloboma, heart defect, atresia choanae [also known as choanal atresia], retarded growth and development, genital abnormality, and ear abnormality).3 There are other, rarer anatomic obstructive processes at the level of the nose in the neonate, ranging from the solid (glioma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and other tumors) to the cystic (dermoid and epidermoid cysts and meningoencephaloceles).

The development of the jaw and tongue may also influence initial airway management during resuscitation. Micrognathia may be seen as an associated finding with other disorders, including trisomies 13 and 18 and Treacher Collins syndrome. Macroglossia most commonly presents as part of a constellation of developmental anomalies, as would be the case in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, trisomy 21, and congenital hypothyroidism. However, macroglossia also may represent underlying pathology in the tongue itself (tumor or vascular malformation) or underdevelopment of the mandible or maxillae.4 The combination of micrognathia, cleft palate, and upper airway obstruction defines the Pierre Robin sequence.

The newborn may present with bilateral congenital paralysis of the vocal cords. Although this typically does not result in true obstruction of the airway, the neonate may cough recurrently and develop respiratory difficulties with feedings. In congenital vocal cord paralysis, the cords are left in the open position, leaving the neonate potentially unable to protect the airway.5 Although not a usual cause of airway obstruction, appropriate airway evaluations should be performed. Likewise, tracheoesophageal fistula typically does not cause an anatomical airway obstruction. However, the newborn with associated esophageal atresia will be unable to clear oral secretions, which may pool in the posterior pharynx and cause a viscous obstruction to the airway.

Congenital high airway obstruction syndrome (CHAOS) may be diagnosed prenatally as either an isolated finding or associated with other anomalies. The level of the airway obstruction may be supraglottic, glottic, or infraglottic and range from laryngeal to tracheal obstruction. The true incidence of this syndrome is unknown but IS considered rare.6

Cystic hygromas are nonmalignant malformations of dilated cystic lymphatic vessels. In the cervical area, they may cause external compression of the larynx or trachea and subsequent obstruction. Chromosomal anomalies, including trisomies 18 and 21, Noonan, and Turner syndromes may be seen in a high percentage of cases.

The most common location for teratomas in the neonate is the sacrococcygeal region. However, these tumors may be found in the cervical area and contribute significantly to airway obstruction. The teratomas may have a variety of tissue present, including every embryonal tissue. The malignant potential of these tumors is unclear (Table 67-1).7

Table 67-1 Causes of Airway Obstruction in the Neonate

Prior to Delivery

Many of the diagnoses that result in partial or complete airway obstruction may be identified prenatally, thus allowing for consultation with appropriate personnel who may be involved in the initial resuscitation and care of the newborn.

PARTIAL AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

Pierre Robin sequence and tracheoesophageal fistula are diagnoses that may be identified prenatally, and consultation with a neonatologist should be considered. During the prenatal consultation, the discussion should include the necessity of airway patency evaluation shortly after birth. If the baby is suspected of having Pierre Robin sequence, it is appropriate to mention that the infant may breathe more reliably in the prone position or may need initial airway support with a nasopharyngeal airway, endotracheal intubation, or placement of a laryngeal mask airway (LMA). The baby with suspected tracheal esophageal fistula likely will require the placement of a suction catheter into the proximal esophageal pouch to assist in clearance of viscous oral secretions.

COMPLETE AIRWAY OBSTRUCTION

If either a large neck mass or congenital high airway obstruction is diagnosed prenatally, referral to a center with expertise in immediate airway management of the fetus is appropriate. Prenatal imaging (ultrasound/magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) findings that would suggest airway compromise from a cervical teratoma or cystic hygroma would include polyhydramnios (from esophageal compression), tracheal deviation, and a heterogeneous or cystic mass in the anterior cervical region. Prenatal findings consistent with congenital high airway obstruction would include a dilated proximal airway, lung hypertrophy, downward displacement of the diaphragm, ascites, or hydrops. During prenatal consultation, a medical geneticist should be involved to determine if there are associated findings or a syndromic component to the diagnosis. A multidisciplinary team will be needed to determine the optimal method of delivery and the potential need to resuscitate the infant while supported by the placental circulation (ex utero intrapartum treatment, or EXIT).8

EQUIPMENT PREPARATION

There should be at least 1 area with close approximation to labor and delivery where neonatal resuscitation occurs. That location should be stocked with all the necessary equipment required to perform a successful resuscitation. For the purposes of this chapter, the focus is on the equipment required to manage the newborn’s airway. Prenatally diagnosed airway issues allow for time and organization of materials that may facilitate the ease of resuscitation. It is an absolute necessity to have immediately available, well-organized airway assistance equipment. Table 67-2 lists the equipment that may be required for airway support.

Table 67-2 Recommended Neonatal Airway Management Equipment