Introduction

As the foregoing chapters indicate, obesity has become a prevalent disease among children and adolescents worldwide and in most countries, the prevalence continues to increase. The causes of childhood and adolescent obesity are multiple and are still being elucidated but, as indicated, the rises in prevalence have been accompanied by marked changes in the food supply, opportunities for physical activity and media use. These shifts in the food and physical environments have changed in developed and developing countries. For example, in the United States, fast food restaurants have become ubiquitous, family meals have declined, soft drink consumption, television viewing and other screen time have increased dramatically, and the likelihood that children or adolescents walk to school or participate in physical education programs in school has declined. While these changes have accompanied the rise in the prevalence of obesity, and most of these changes have been associated with obesity in cross-sectional or longitudinal studies, few studies have shown that interventions directed at these targets successfully reduce the prevalence of obesity. It seems likely that no single change in the food, physical activity or media environment can account for the current epidemic. Because it also seems unlikely that any single change in any of the aforementioned behaviors will be powerful enough to reduce the prevalence of obesity, efforts to address multiple factors within the food, physical activity and media environments simultaneously would seem the most appropriate strategy to address the epidemic. To change these environments will probably require major shifts in social norms which will not be likely without a social movement of the breadth and scale of other social movements, 1 such as that which reduced tobacco consumption.

In this chapter, I use lessons learned from the efforts to control tobacco consumption as a potential model for obesity prevention and control. I compare and contrast the current status of efforts to prevent and control obesity to outline the needs and options for the way forward. Although this analysis focuses on the United States, parallels to experiences elsewhere may inform the way forward.

Recognition of the health effects

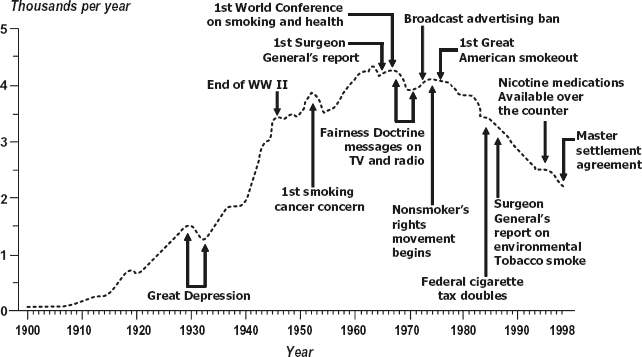

One of the first lessons from tobacco control was that as the prevalence of the adverse consequences of cigarette consumption were increasingly well-documented, efforts to increase public awareness of the health effects also grew, and generated an increased awareness of the adverse effects of smoking on health.2 The rise and fall of cigarette consumption is shown in Figure 34.1.3 As is apparent, the rise in per capita cigarette consumption began in the 1900s and continued to rise in an almost linear fashion until the 1950s when the first reports linking tobacco to adverse health outcomes began to appear. Thereafter, as more data linking smoking and disease appeared, and as restrictions began to be instituted on advertising for cigarettes, per capita cigarette consumption began to plateau. The association of the increased awareness of the adverse health effects of tobacco with the plateau in cigarette consumption suggests that these two phenomena may be causally related.

Figure 34.1 Annual adult per capita cigarette consumption and major smoking and health events–United States, 1900–1998.

With respect to obesity in the United States, the publication of annual state-based maps (www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/obesity/trend/index.htm) derived from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System that showed state-by-state changes in the prevalence of obesity prompted an increased awareness of the rapid changes in prevalence in the US population. These data were buttressed by National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data that demonstrated that the prevalence of obesity in US children and adolescents was relatively stable until 1980, and then began to increase steadily. 4,5 Although the adverse health effects of obesity were known to physicians and public health practitioners, the public may not have been aware of these effects.

In the United States, the rapid rise in prevalence was accompanied by stories in the media about obesity and its health consequences. For example, from 1999 to 2004, articles in the print media and newswires related to obesity increased from approximately 8,000 articles in 1999 to over 28,000 articles in 2004.6 Perhaps in response to the intensive attention to the prevalence and consequences of obesity, its prevalence in children and adolescents of both genders, in black, white and Mexican American youth,7 and adult females8 in the United States appears to have begun to plateau. Furthermore, plateau or decreases in the prevalence of childhood obesity have also been reported in Arkansas9 and Texas (D. Hoelscher, personal communication). Although there is no assurance that increased attention to the prevalence, health effects and causes of obesity contributed to the plateau in prevalence, it is possible that this plateau mirrors the experience with tobacco, where awareness of the adverse health effects of tobacco use was associated with a plateau in cigarette consumption, but not a decline. With respect to obesity, the stabilization of prevalence suggests we may be at or approaching a similar turning point.

The role of policy and environmental change

Although initiatives in the United States to change tobacco policy began at the state or local level, a number of federal reports helped provide the impetus for change.10 For example, the 1964 Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health compiled the evidence on the adverse consequences of smoking. Subsequent efforts by Surgeons General to focus on the health impact of tobacco use provided the scientific rationale for local efforts at control. Likewise, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) ruled in 1964 that warning labels were required on cigarette packs, and that tobacco advertising should be strictly regulated. Although Congressional legislation temporarily pre-empted the FTC’s authority to regulate tobacco advertising, the battle around advertising had begun. Eventually, a ruling mandating counter-advertising on television and, subsequently, a ban on tobacco advertising on television, was a very visible indication to the public that the adverse effects of tobacco were being addressed at the federal level.

However, the successful reduction in per capita cigarette consumption resulted from the implementation of a variety of policy initiatives in multiple settings.3 These included the restriction of smoking in public buildings, evidence-based school curricula, counter-marketing, increased taxes on cigarettes, enforcement of laws that prohibited sales of cigarettes to minors, and smoking cessation programs. Almost all of these initiatives resulted from local or state-based efforts. For example, Arizona passed the first statewide ban on smoking in public places in 1973, and by 1975 similar legislation had been passed in 10 states.10

With respect to obesity, although a number of behaviors have been targeted for change, such as sugar-sweetened beverage intake, fruit and vegetable intake, television time, intakes of high-energy density foods, breastfeeding and physical activity, the portfolio of successful policy and environmental strategies to address these behaviors is limited. However, a number of communities in the United States and elsewhere have initiated efforts to begin to prevent and control obesity, and surveys like the School Health Policies and Programs Survey in the USA suggest that changes at multiple levels have begun in US schools.11 Like the early efforts at tobacco control, these activities are local, but it is not yet clear how consistently these behaviors are being targeted, what policy initiatives are being employed, what critical mass of policy change is necessary to change the prevalence of obesity, and whether these topics are consistently the focus of evaluation.

Another characteristic of social movements is the perception of a common threat. In 1967, as described above, application of the Fairness Doctrine to tobacco advertising led to radio and television counter-advertising of cigarettes. 12,13 The advertisements about the adverse health effects of cigarettes produced a decrease in cigarette consumption,10 which led the tobacco industry to negotiate the elimination of radio and television advertising for cigarettes. Somewhat later, the public became aware of the efforts of the tobacco industry to conceal their knowledge of the health effects of tobacco and to market their products to adolescents.14 These actions on the part of industry contributed to the recognition of cigarette smoking as a threat to youth, and passive smoke exposure as a threat to the health of non-smokers.2 The efforts of the cigarette companies to persuade adolescents to smoke, to obscure the health effects of tobacco, and to resist efforts to control tobacco use quickly made them a common enemy.

Although survey data confirm that a 40% of Americans consider childhood obesity a serious problem,15 and 27% of adults consider obesity the most important health issue for children, 16 many parents of obese children do not recognize that their child is obese. 17–19 These observations indicate that a disjunction exists between the public’s concern about childhood obesity and the recognition that their child shares the problem. Use of the term “obesity” may contribute to the perception that obesity is not an immediate threat, because the term has a pejorative connotation, and in common use generally refers to individuals with severe obesity. The pejorative connotation of the term obesity may also explain why obesity is not an acceptable term for providers to use to discuss excess weight in adolescent20 or adult patients.21 Therefore, one of the earliest challenges in the evolution of a movement to address obesity is the need to identify a common frame that mobilizes support for policy initiatives or promotes behavior change. Because obesity is perceived as a social concern but not necessarily a personal threat, and because the term obesity is not a term that can be used to personalize the threat, further emphasis on the obesity epidemic or the health effects of obesity may not generate the commitment necessary to mobilize the public around environmental change.

A second issue with respect to the threat posed by obesity is the lack of a single readily identifiable widely accepted cause. Tobacco in any quantity is harmful, whereas the same cannot be said about food. Furthermore, efforts in the United States to identify fast food, sugar-sweetened beverages, television time, or television advertising as the factor(s) responsible for the epidemic of childhood obesity have not generated the political will necessary to change them, suggesting that they are not widely perceived as a significant threat.

Consistent themes that led to efforts to control tobacco were the public’s health, especially the need to protect youth, and the health of non-smokers.2 With tobacco, the tobacco companies and their products quickly became the targets of efforts to reduce smoking. Limiting their ability to advertise and using economic strategies such as tobacco taxes to reduce purchases were readily accepted strategies. In contrast, it follows from the lack of perception of obesity as a common or immediate threat that other reasons to change the nutrition and physical activity environments may provide more persuasive incentives for a broad population approach to obesity. For example, many of the strategies to improve the diet and physical activity are shared with efforts to reduce global warming. Farm-to-market strategies may provide fruits and vegetables at lower cost without incurring the costs of fuel and the production of carbon dioxide that result from the transportation of fruits and vegetables across the country. Likewise, use of public transportation22 or walk-to-school programs23 reduce car use and increase physical activity. Both of these examples engage groups that may not see these strategies as obesity prevention and control strategies, but might embrace them because of their impact on global warming.

Another alternative may be to frame the nutrition and physical activity strategies to address obesity in terms of social justice. In the United States, significant ethnic disparities exist with respect to access to parks and recreation facilities,24 or supermarkets that provide healthy choices of fruits, vegetables, or other lower calorie food choices.25 Access and the promotion of parks and recreation facilities is a recommended strategy to increase physical activity,26 and access to supermarkets may improve food choices in neighborhoods where the population relies on corner shops for much of their food supply.27 Characterization of access to healthy food choices and physical activity facilities as a reflection of social inequity may provide a more compelling rationale to generate change than the potential contribution of these inequities to obesity.

Although wellness is a more elusive concept than obesity, good nutrition and physical activity are generally recognized as important components of wellness. In the United States, the economic costs associated with chronic diseases have led to a growing interest in wellness as a way to contain those costs. A recent estimate suggested that 12% of the rise in medical costs between 1987 and 2000 were attributable to obesity related illnesses. 28 The observation that one third of children born in the year 2000 in the United States will develop Type 2 diabetes mellitus at some time during their lifetime29 and the costs associated with this disease are likely to overwhelm an already burdened medical care system.

In 2005, US medical costs were approximately 15% of the gross domestic product (GDP), and by 2015, were expected to rise to 20% of the GDP.30 The CEO of General Motors recently stated that medical costs paid by his company added to the costs of GM cars and, therefore, impaired GM’s international competitiveness.31 Furthermore, the rise in medical costs has increasingly led employers to begin shifting the payment of insurance plans to their workforce, 32 but also to the exploration and investment in worksite wellness programs. However, whether efforts in the business sector are sufficient to mobilize broader segments of the population remains uncertain. Furthermore, efforts to contain medical costs, as well as the increase in medical costs borne by consumers may drive changes in behavior and create a demand for environmental change.

The history of social movements is characterized by grass-roots groups that mobilize in response to a common threat and are committed to change.1 An important element of tobacco control was the development of a variety of groups with shared or overlapping agendas, which worked separately on some issues but together on others to limit tobacco use at the local and state level.2 These efforts often began locally, but as a result of the communication that developed between the groups and the networks, these strategies spread to other venues. For example, regulations to require smoking and non-smoking areas in public buildings were implemented in Minnesota in 19752 and spread from there to other locales and states.

Although obesity has been recognized as a signifi-cant problem by a variety of elites, such as medical providers, public health authorities, philanthropies, and some business and government leaders, the public has not mobilized broadly around common strategies to improve nutrition and physical activity in children and adolescents. One potential explanation is that obesity is still widely perceived as an issue of personal or parental responsibility rather than one for which broad changes in policy are required. Nonetheless, as indicated above, a number of schools and communities have committed to change. Because many of these efforts have been supported by local organizations including philanthropic trusts, it remains uncertain whether these efforts are imposed on the community with only limited community mobilization, or are community based or community driven. Only the latter two scenarios are likely to mobilize substantial numbers of individuals with a sustained commitment to change. Furthermore, the efforts in communities to control obesity are not yet connected or coordinated. An important challenge is how to connect these local efforts to broaden the base of support necessary for the prevention and control of obesity.

Tobacco control has progressed because of a successful social movement that has been coupled with policy and environmental change. Surveillance led to an awareness of the adverse health effects of tobacco use and a broad appreciation of the human costs associated with tobacco use. Reports from the federal government regarding the hazards of tobacco use reinforced local initiatives. Cigarettes and the companies that produce them became a common enemy, galvanizing local communities and states to act to control access to tobacco and sales to minors. Successful control occurred because of the implementation of policy and environmental initiatives in a variety of venues, which were made possible because of shifts in social norms related to smoking.

If we are to successfully control obesity, it may be useful to conceptualize our approach to obesity prevention and control as a social movement. Although some data would suggest that we have successfully established obesity as a medical and public health concern, a number of key elements that characterize social movements are not yet in place. Obesity is not perceived as a common threat, and it is not clear that obesity is the appropriate frame to mobilize broad segments of the population. A variety of other frames may engage a broader segment of the population, and may improve nutrition and physical activity without specifically targeting obesity. To build the social movement necessary to address obesity, our efforts should be channeled to identifying strategies that resonate with a broad group of supporters, to remain flexible with respect to they way we promote and frame our objectives, and to link efforts in diverse settings to form a more comprehensive approach across settings and constituencies.

1 Davis GF, McAdam D, Scott WR, Zald MN eds: Social Movements and Organization Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

2 Wolfson M: The Fight Against Big Tobacco. Hawthorne NY: Aldine de Gruyter, 2001.

3 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Tobacco use —United States, 1900–1999. 1999; 48: 986–993. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4843a2.htm (accessed 15 May 2008).

4 Troiano RP, Flegal KM: Overweight children and adolescents: description, epidemiology, and demographics. Pediatrics 1998; 101: 497–504.

5 Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM: Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA 2006; 295: 1549–1555.

6 International Food Information Council Foundation: Figures retrieved from Lexis-Nexis searches on “obesity” or “obese” in U.S. and international newspapers and news-wires. April 2008.

7 Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM: Overweight and high body mass index (BMI)-for age among U.S. children and adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA 2008; 299: 2401–2405.

8 Ogden CL, Carroll MD, McDowell MA, Flegal KM: Obesity among adults in the United States—no statistically signifi-cant change since 2003–2004. NCHS Data Brief, November 2007. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db01.pdf (accessed 11 May 2008).

9 Arkansas Center for Health Improvement: Assessment of childhood and adolescent obesity in Arkansas. Year four (Fall 2006–Spring 2007). www.achi.net/publications (accessed 11 May 2008).

10 Department of Health and Human Services: Smoking and Tobacco Use: 2000 Surgeon General’s Report—Reducing Tobacco Use. Washington DC, US Public Health Service, 2000. Available at www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/sgr_2000 (accessed 10 May 2009).

11 Kann L, Brener ND, Wechsler H: Overview and summary: school health policies and programs study 2006. J Sch Health 2007; 77: 385–397.

12 Ibrahim JK, Glantz SA: The rise and fall of tobacco control media campaigns, 1967–2006. Am J Public Health 2007; 97: 1383–1396.

13 Bero L: Implications of the tobacco industry documents for public health and policy. Annu Rev Public Health 2003; 24: 267–288.

14 Ericksen M: Lessons learned from public health efforts and their relevance to preventing childhood obesity. In: Koplan JP, Liverman CT, Kraak VI, eds. Preventing Childhood Obesity; Health in the Balance. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2005: 343–375.

15 Evans WD, Finkelstein EA, Kamerow DB, Renaud JM: Public perceptions of childhood obesity. Am J Prev Med 2005; 28: 26–32.

16 Charleton Research Company for Research! America Endocrine poll 2006. www.endo-society.org/media.press/2006/OBESITYCITEDNUMBERONEKINDSHEALTHISSUE.cfm (accessed 10 May 2005).

17 Mamun AA, McDermott BM, O ’ Callaghan MJ, Najman JM, Williams GM: Predictors of maternal misclassifications of their offspring’s weight status: a longitudinal study. Int J Obes 2008; 32: 48–54.

18 Baughcum AE, Chamberlin LA, Deeks CM, Powers SW, Whitaker RC: Maternal perceptions of overweight preschool children. Pediatrics 2000; 106: 1380–1386.

19 Maynard LM, Galuska DA, Blanck HM, Serdula MK: Maternal perceptions of weight status of children. Pediatrics 2003; 111: 1226–1231.

20 Cohen ML, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Young-Hyman D, Yanovski JA: Weight and its relationship to adolescent perceptions of their providers (WRAP): a qualitative and quantitative assessment of teen weight-related preferences and concerns. J Adolesc Health 2005; 37: 163e9–163e16.

21 Wadden TA, Didie E: What’s in a name? Patients’ preferred terms for describing obesity. Obes Res 2003; 11: 1140–1146.

22 Frank LD, Engelke PO, Schmid TL: Health and Community Design. Washington DC: Island Press, 2003.

23 Staunton CE, Hubsmith D, Kallins W: Promoting safe walking and biking to school: the Marin County success story. Am J Public Health 2003; 93: 1431–1434.

24 Cradock AL, Kawachi I, Colditz GA et al: Playground safety and access in Boston neighborhoods. Am J Prev Med 2005; 28: 357–363.

25 Karpyn A, Axler F: Food geography: how food access affects diet and health. www.thefoodtrust.org/pdf/Food%20Geography%20Final.pdf (accessed 11 May 2008).

26 Task Force on Community Preventive Services: Recommendations to increase physical activity in communities. Am J Prev Med 2002; 22(4S): 67–102.

27 Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Nettleton JA, Jacobs DR Jr: Associations of the local food environment with diet quality——a comparison of assessments based on surveys and geographic information systems. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 167: 917–924.

28 Thorpe KE, Florence CS, Howard DH, Joski P: The impact of obesity on the rise in medical spending. Health Affairs 2004; Web Exclusive. Health Aff 2004 (20 October); 10.137/hlthaff..w4-480.

29 Narayan KMV, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ et al: Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. JAMA 2003; 290: 1884–1890.

30 Appleby J: Health care tab ready to explode. United States of America and Today 2005 (24 February); p. 1A.

31 Connolly C: U.S. firms losing health care battle, GM chairman says. Washington Post 2005 (11 February); Financial; p. E01.

32 Pear R: Nation’s health spending slows but it still hits a record. New York Times 2005 (11 January); p. A15.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree