Summary and recommendations for practice

- Interventions should be complex and ecological in nature, addressing the multiple and interactive influences on obesity, of which the primary school is one part.

- Interventions within schools should be multi-faceted covering curriculum, policy and social and physical environments.

- School interventions should be developed and implemented with community involvement.

- Interventions within schools should address multiple rather than single risk behaviors.

- Interventions should be implemented within a rigorous evaluation framework to develop an adequate evidence base and to assess their impact on health inequalities.

References were searched and retrieved from international databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Cochrane databases from 1991 to February 2008. Effective interventions were recommended mainly based on findings in systematic reviews.

Rationale/importance of primary setting

Childhood obesity has increased rapidly over the past two decades, both in developing and industrialized countries.1 Interventions targeted at primary school-aged children are considered critical to prevent and control this disease since food and physical activity related behaviors are established early in life and persist into adulthood.2 The life-course approach to public health suggests that interventions in early life may define lifelong behaviors and protect children from developing unhealthy dietary habits. Children aged 5–11 have been identified as the optimal group to target for interventions on physical activity and healthy food preferences.3 School settings are the prime focus for preventive actions since they cover most children in a country. Most children attend school approximately 180 days/year for six or more hours per day.4 Children can easily be reached to assess their health needs, receive tailored interventions such as health education and physical activity promotion, be provided with healthy school meals, and be affected by environmental factors that condition obesity in children.2 This is well recognized in the Health Promoting School s (HPS) program, launched by World Health Organization (WHO). This presents a collaborative, interactive and participatory model for health promotion in the school by strengthening and enriching, the curriculum, developing a supportive environment reinforcing health enhancing behaviors, and creating strong links and access to community resources.5

Defining the primary school settings

This chapter examines the need for interventions in light of current trends in overweight and obesity in children as a global concern. In this context, the significance of school-based interventions goes beyond the opportunity to address the determinants that exist in the school environment; schools also provide an opportunity to reach individual children, families and the wider community.

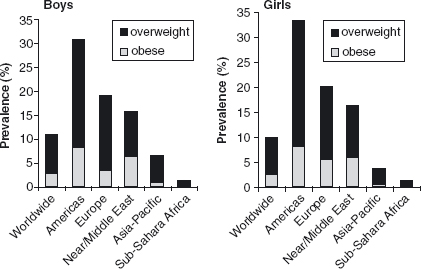

It is difficult to estimate the true extent of the obesity problem among children, because diverse classifications of childhood obesity have been used across study populations. However, using current International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) estimates, one out of ten school- aged children in the world is overweight or obese, with the highest prevalence occurring in the Americas (Figure 10.1).2

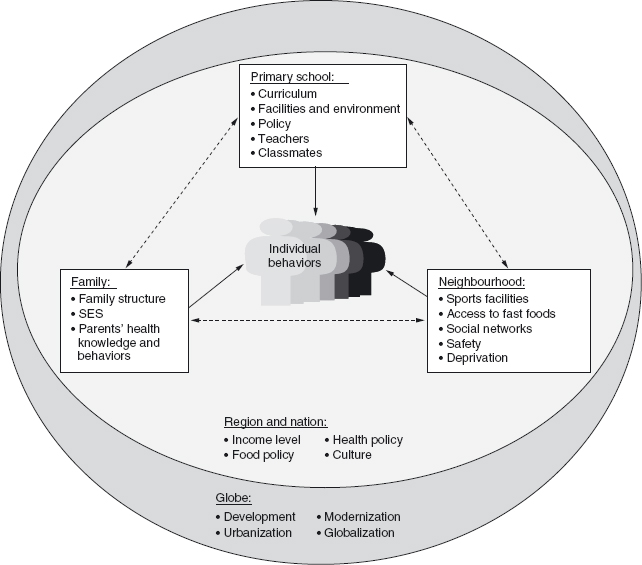

As economies grow, obesity shifts from the more affluent to less affluent groups. Social and economic development, modernization, urbanization and globalization collectively nurture unhealthy eating patterns and physical inactivity and constitute the main causes of obesity. Figure 10.2 draws on a socio-ecological perspective 6–8 to illustrate how determinants of childhood obesity at different levels—namely, at individual, family-school-neighbourhood (community), national, and global—may interact and contribute to the current epidemic of obesity.

As shown in Figure 10.2, schools play a key role in determining a child’s immediate environment. Meals and snacks at schools form part of the child’s overall diet, and the physical environment of the school, together with school policy, determine activity patterns. Furthermore, curriculum helps to form children’s knowledge and behaviors both in nutrition and physical activity. Public primary schools in some countries provide meals (breakfast and/or lunch) to the children, either at no cost or subsidized in a significant way; in most cases the programs are designed with the objective of meeting established nutritional standards. Unfortunately, these programs do not always offer fresh vegetables and fruits and other healthy foods (lean meats and fish) as part of the menu. School meals are an important source of total daily energy intake and, especially for low-income children, may mitigate hunger and serve to prevent undernutrition.

Both state-funded and private schools in developed countries, and private schools in developing countries, may have a cafeteria inside the school offering meals à la carte, which generally comply with nutritional standards. In addition, food items can be sold in vending machines and/or tuck shops and, in general, are not regulated. In some cases, unhealthy foods cannot be sold during meal periods in the food service areas; nevertheless, they can be sold anywhere else in the school. The kinds of foods sold in school vending machines are mostly high-fat and high- sugar nutrient poor foods and beverages that promote weight gain. Because the sale of these foods can generate revenue to the school to support different types of activities, regulating the sale of these items can be quite difficult. Furthermore, offering this type of foods for sale inside the school contradicts the health messages that children receive in the classroom or in health promotion efforts.4

Schools also influence children’s level of physical activity. School-based physical activity or physical education programs help primary school children to remain active. Schools should have good quality physical education classes (PE) (a minimum of three times a week to total 135 minutes), health education, sufficient recess time and an intramural sports program.9 Unfortunately, PE classes are often undervalued despite their importance in achieving fitness, skills and health. Because playtime is a necessary activity for the release of energy and stress and it may also help children concentrate in the classroom. It should not be scheduled before or after PE classes. Intramural activities can offer opportunities to increase physical activity, but mostly better-off children take advantage of them, because even though the school may offer them, lower-income students may have transportation problems.10

Health education including formal instruction in healthy eating and promotion of physical activity is needed in all grades in order to improve children’s knowledge and encourage children to adopt a healthy lifestyle. Research supports the use of behavioral techniques to achieve effectiveness in this task.11 Aspects of health education can also be integrated into the lesson plans of other subjects such as mathematics, language, art, and so on. In addition to health education, school health centers can play an important role offering students, primary care or referral services to other health centers. Such centers can be found in state-funded and private schools in developed countries and private schools in developing countries, and may provide screening as well as information on prevention and treatment of obesity. In addition, schools can provide opportunities to implement obesity-prevention programs through after-school programs. In the United States there are several large-scale federally funded after-school programs to prevent obesity among low- income children. These may include academic enrichment, physical activity and free snacks.12

School-based obesity prevention programs can also provide a means of reaching the family. Family involvement and active participation by parents in obesity prevention is crucial; nevertheless, this can be quite difficult. Some programs that have achieved high rates of recruitment and retention have used incentives such as food, transportation and rewards. A promising initiative to involve parents may be to open school facilities such as gyms and swimming pools after school and at weekends. Another strategy of family involvement is parental notification of the child’s BMI. Kubik et al13 reports that parents of elementary school children are generally supportive of BMI reporting, but they want assurance about student privacy, respect and to know that overweight children will not be stigmatized. The US Institute of Medicine endorses BMI reporting and making it available once a year to parents with appropriate indications in cases where the child is overweight. This activity should be tested in other societies so as to assess its effectiveness in different settings. The box below lists some of the issues that should be taken into account before deciding whether to use BMI reporting, and the chapter on ethics within this book provides more detail on ethical considerations.

Parental notification of children’s BMI

- Which parents are going to be notified?—all of them, or only parents of overweight children.

- What will the parents be told when notified?

- Will they be advised to seek medical guidance or will they receive other recommendations? Are these readily available?

Finally, schools and school-based prevention programs can help to provide links with communities and families. For example, some schools have programs that link local farmers as suppliers for school meals. These programs have the advantage of providing high-quality produce and supporting local agriculture. Other initiatives include walking and cycling to school which, being a daily activity, can provide substantial energy expenditure over the school year.14 Unfortunately, active commuting to schools has declined dramatically in recent decades. The reasons reported include long distances, traffic danger and crime. A final means by which schools can involve the larger community is through School Wellness Programs. Because schools are large employers, they become ideal places for health promotion for teachers and staff. This could encourage them to value the importance of healthy eating and physical activity and eventually to become role models for their students and their families

Interventions in primary school settings may be grouped together by aspects such as the aim, target population, intervention levels, extent of stakeholders involved, determinants addressed, specific intervention components, duration of the intervention and the outcomes measured. The intervention aim can be focused primarily on reducing obesity, or this can be a component of an intervention with another main goal (e.g., interventions for preventing childhood diabetes). Furthermore, the targeting can be primary prevention (addressing the general population), secondary prevention (addressing the population at risk of obesity), tertiary prevention (treating the obese population), or integrated/comprehensive (combination of the three level preventions).

Intervention programs may take place only in one school (single level), or multiple schools at the community, region, national, and even international levels (multiple levels). The intervention may engage any combination of stakeholders including individual participants or organizations from the health sector, non-health sector, policy-makers, teachers, school nurse, parents and grandparents. A number of determinants can be addressed, including one or any combination of the determinants as described in Table 10.1. In general, interventions lasting less than one year are defined as short-term, while those lasting one year or more are long term.15 Considering that behavior change is central to preventing obesity, the effectiveness of short-term interventions may be biased and even regressive whereas effective long-term interventions are more promising. Commonly used outcomes can be divided into the following categories: body composition (e.g., BMI, fat distribution, prevalence of obesity/overweight, skin-fold thicknesses); nutrition/dietary habits (e.g., food choice, food consumption, energy intake and sources); physical activity (e.g., frequency, duration, intensity, sedentary behaviors); psycho-social factors (e.g., self-esteem, body image, stress level, feelings of support); knowledge (e.g., knowledge of chronic disease risk factors, nutrition and physical activity requirements for optimal health); and policy options (e.g., using a panel of experts and an appropriate framework such as a socio-ecological model/life-course/social model of health.16

Table 10.1 Intervention components.

| Level of determinants | Components |

| Individual determinants | |

| Substantial dietary modifications | |

| Substantial physical activity modifications | |

| Psycho-social interventions focusing on self-esteem, body image, peer support and stress management | |

| Behavior modifications focusing on motivational reinforcement | |

| Health education on diet and physical activity | |

| Tailored individually | |

| Subject-directed (subjects actively engaged in the programs) | |

| Familial determinants | |

| Health education | |

| Dietary modifications | |

| Physical activity modifications | |

| Knowledge and attitude | |

| Support from family members | |

| Environmental determinants | |

| Create or advocate for healthy social environments | |

| Physical environments (e.g., sports equipment, time and place, transport, canteen, snack shop, vending machines) | |

| Cultural environments (e.g., media and culture) |

In the absence of other evidence, experts suggest that these should be multi-component in nature. It is important to take into consideration that schools are faced with multiple curricular obligations with limited financial and staff resources. Even well-intentioned and motivated teachers have reported limited classroom time to address health education adequately.

What has been proven effective

The primary focus of this chapter is interventions that include a primary prevention approach at the school- based level on which a number of reviews have been conducted.15–24 The aim of the intervention is a key inclusion/exclusion criterion used by various reviews. The Cochrane review series, most recently updated by Summerbell et al,15 aimed to examine the effectiveness of interventions on overweight/obesity prevention, whereas Flynn et al25 and De Mattia et al22 included aims other than obesity prevention. Interventions struggle to achieve changes in BMI despite finding effectiveness on some behavioral and other outcomes.26 In addition to intervention aim, another critical issue is whether interventions are carried out at a single school or within the same small community (single level) or at multiple schools in multiple communities or districts. Doak et al25 found that effective interventions had, on average, fewer participating schools, in particular, single-level interventions that were carried out in only a few schools. This may be due to the ability of such interventions to target the specific needs of the children. Although interventions have found sub-group differences in intervention effect,25,27 Flynn et al25 found that only four interventions addressed the health concerns of special needs populations. In addition, Flynn et al25 confirmed the preliminary findings15,24 of earlier reviews that boys require special targeting for intervention.

Comparisons of specific elements of study design show some consistent trends but, unfortunately, there are not enough interventions for statistical comparisons. Reviews have identified that interventions that target physical activity through compulsory physical education19 or reduced TV viewing or soft drinks interventions20,24,28 are the most promising. A meta-analysis that pooled results from 12 interventions showed that interventions with both nutrition and physical activity resulted in significant reductions in body weight compared to controls,21 with a stronger effect for interventions that involved parents. In contrast, Summerbell et al15 concluded that studies combining diet and physical activity did not significantly improve BMI. Likewise, Doak et al24 also identified multiple component interventions as less likely to be effective. However, evidence shows that school-based interventions should target only a few behaviors and that these require an “environmental-behavioral” synergy: that is, food and physical activity environments should echo and support the targeted behaviors. This includes the type of foods offered in schools, infrastructure for physical activity and good quality PE classes.29

If interventions are to provide long-term solutions, they must not only be shown as effective, but must also be sustainable. Whereas early reviews had too few studies to compare results, more recent reviews show consistent evidence for short-term rather than long-term benefits of interventions.15,24,25 While few studies have been shown as effective a year or more after the initial intervention, fewer still continue outcome evaluation a couple of years after the intervention. Unfortunately, in one such example,28 the intervention effect at one year was lost after three years of follow-up. Sharma18,26 argues that intervention length can be shortened if the intervention is based on behavior theory. However, sustainable interventions effective over a long time frame are needed to reverse rising trends of overweight and obesity.

In a review of interventions specifically focused on physical activity, DeMattia et al22 were only able to assess outcomes using BMI because of a lack of comparable outcomes. Although these authors found the majority (4 out of 6 interventions) to be effective, adiposity measures would have been more appropriate. Many reviews have also chosen to focus on BMI-based measures where multiple and/or conflicting results are presented. The review by Lissau30 argues that focusing on BMI outcomes is likely to produce a false negative if used to assess physical activity interventions. In fact, the literature provides evidence of interventions that show no reduction in BMI outcomes, but reductions in skin-folds, indicating improvements in body composition. Existing evidence illustrates the need to ensure the quality of interventions and to develop systematic methods for evaluating multiple, conflicting outcomes in a manner that is unbiased and appropriate to the study design.

The school setting is subject to a number of barriers in implementing sustainable obesity prevention programs31–33 with programs requiring infrastructure and resources that may well not exist in poor schools. It is also clear that there is a need to develop our understanding of the multiple, interactive and cumulative obesogenic influences on primary school pupils within the “obesity system”. Recognizing and addressing this complexity highlights that schools “definitely cannot counteract all the stressors and tensions originating in other life spheres such as unfavorable economic conditions, dysfunctional families or lack of supportive friends”34 and “that schools are only one component and probably quite small in their influence in altering a person’s health status”.35

Given these reservations, a number of recommendations can be made regarding obesity prevention in primary schools, not least of these is the need to develop the evidence base. Achieving change is hampered by a lack of robust scientific evidence about how to intervene effectively in ways that reduce, rather than exacerbate, health inequalities.36 Systematic reviews have highlighted the need for improved evaluation designs that draw on mixed methods in particular (e.g., Norton et al).37 There is also a need to increase the number of comparative studies outside Europe and North America, in countries where problems of undernutrition still exist but where obesity is rapidly emerging.38,39

Study methods also require development, with a need to develop standardized self-report measures and to assess their relationship to changes in BMI in large-scale trials. Indeed, the measurement of obesity in children continues to be controversial, with epidemiological evidence demonstrating that measures of BMI are sensitive to population differences in age of puberty40 and height.41,42 More worrisome is the potential bias in the error in weight-based measures, as evidence indicates that effectiveness differs based on the outcome used. It also noted that a number of systematic reviews to date have not provided information on costs or cost–effectiveness, 35,43 presumably because this was not addressed in the primary studies.

Given this lack of evidence, a number of tentative suggestions for future policy can be made. Even though there has been a tendency for initiatives to focus on single risk behaviors,14,44,45 emerging evidence indicates that such behaviors cluster, suggesting a need for complex interventions to address multiple behaviors simultaneously. It has also been argued that “a multifaceted approach is likely to be most effective, combining a classroom program with changes to the school ethos and/or environment and/or with family/community involvement”.46 The importance of such multi-factorial interventions was clearly set out in the 1986 Ottawa Charter and was reiterated in the WHO’s more recent Bangkok Charter in 2005.47 While providing the impetus for a growth in settings-based interventions, many such interventions have been criticized for focusing on the most accessible setting and groups and for conceptualizing setting as a channel of delivery rather than a dynamic context that both shapes and is shaped by those within it.48

This is compounded by a lack of understanding of the interactive effect of interventions, both within and across such contexts. Indeed, a recently published synthesis of evidence indicated mixed evidence of effectiveness and concluded that “there is a lack of evidence on all the elements that contribute to an effective health promotion program or to the health promoting schools approach as a whole”.49 This suggests that mono-behavior interventions that fail to address behavioral contexts are unlikely to reduce health inequalities or develop sustainable health improvement. Evaluating such an approach highlights particular challenges relating to causal attributions of effects and the time required for intervention implementation. Such an approach may require long-term evaluation designs that address the intervention as a complex adaptive system. As Hawe et al50 state, there is a need to reverse current custom and to begin to theorize about “complex systems and how the health problem or phenomena of interest is recurrently produced by that system”.

1 Popkin B: The nutrition transition and obesity in the developing world. J Nutr 2001; 131: 871S–873S.

2 Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R: IASO International Obesity TaskForce. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev 2004; 5(Suppl. 1): 4–104.

3 Brown T, Kelly S, Summerbell C: Prevention of Obesity: a review of interventions. Obes Rev 2007; 8: (Supp. 1): 127–130.

4 Peterson K, Fox M: Addressing the epidemic of childhood obesity through school-based interventions: what has been done and where do we go from here? J Law Med Ethics 2007; 35: 113–130.

5 WHO Health Promoting Schools. Global School Initiative. www.who.int/school_youth_health/gshi/en/ (accessed 22 February 2008).

6 Kumanyika S: Environmental influences on childhood obesity. Ethnic and cultural influences in context. Physiol Behav 2007. doi: 1016/j.physbeth.2007.11.019

7 McLeroy K, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K: An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Behav 1988; 15: 351–377.

8 Bauer G, Davies K, Pelikan J: The EUHPID Health Development Model for the classification of public health indicators. Health Promot Int 2006; 21: 153–159.

9 Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C, Newhouse D: The impact of state physical education requirements on youth physical activity and overweight. Health Econ 2007; 16: 1287–1301.

10 Floriani V, Kennedy C: Promotion of physical activity in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2008; 20: 90–95.

11 Baranowski T: Advances in basic behavioral research will make the most important contributions to effective dietary change programs at this time. J Am Diet Assoc 2006; 106: 808–811.

12 Story M, Kaphingst KM, French S: The role of schools in obesity prevention. Future Child 2006; 16: 109–142.

13 Kubik M, Story M, Rieland G: Developing school-based BMI screening and parent notification programs: findings from focus groups with parents of elementary school students. Health Educ Behav 2007; 34: 622–633.

14 Reilly J, McDowell Z: Physical activity interventions in the prevention and treatment of paediatric obesity: systematic review and critical appraisal. Proc Nutr Soc 2003; 62: 611–619.

15 Summerbell C, Waters E, Edmunds L, Kelly S, Brown T, Campbell K: Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 3 (Art. No. CD001871).

16 McNeil D, Flynn M: Methods of defining best practice for population health approaches with obesity prevention as an example. Proc Nutr Soc 2006; 65: 403–411.

17 Mueller M, Asbeck I, Mast M, Lagnaese L, Grund A: Prevention of Obesity—more than an intention. Concept and first results of the Kiel Obesity Prevention Study (KOPS). Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25(Suppl. 1): S66–S74.

18 Stevens J, Alexandrov A, Smirnova S et al: Comparison of attitudes and behaviors related to nutrition, body size, dieting, and hunger in Russian, Black-American, and White-American adolescents. Obes Res 1997; 5: 227–236.

19 Connelly J, Duaso M, Butler G: A systematic review of controlled trials of interventions to prevent childhood obesity and overweight: a realistic synthesis of the evidence. Public Health 2007; 121: 510–517.

20 Sharma M: School-based interventions for childhood and adolescent obesity. Obes Rev 2006; 7261–7269.

21 Katz D, O’ Connell M, Njike V, Yeh M, Nawaz H: Strategies for the prevention and control of obesity in the school setting: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008; 32(12): 1780–1789.

22 DeMattia L, Lemont L, Meurer L: Do interventions to limit sedentary behaviours change behaviour and reduce childhood obesity? A critical review of the literature. Obes Rev 2007; 8: 69–81.

23 Campbell K, Waters E, O’Meara S, Summerbell C: Interventions for preventing obesity in childhood. A systematic review. Obes Rev 2001; 2: 149–157.

24 Doak C, Visscher T, Renders C, Seidell J: The prevention of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a review of interventions and programmes. Obes Rev 2006; 7: 111–136.

25 Flynn M, McNeil D, Maloff B et al: Reducing obesity and related chronic disease risk in children and youth: a synthesis of evidence with “best practice” recommendations. Obes Rev 2006; 1: 7–66.

26 Doak C, Heitman BL, Summerbell C, Lissner L: Prevention of childbood obesity—what type of evidence should we conside relevant: Obes Rev 2009; May 10(3): 350–356.

27 Webber L, Osganian S, Feldman H et al: Cardiovascular risk factors among children after a 2 1/2-year intervention-The CATCH Study. Prev Med 1996; 25: 432–441.

28 Sharma M: International school-based interventions for preventing obesity in children. Obes Rev 2007; 8: 155–167.

29 Committee on Prevention of Obesity in Children and Youth. FNB, IOM, Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences, 2004.

30 Lissau I: Prevention of overweight in the school arena. Acta Paediatr Suppl 2007; 96: 12–18.

31 Hesketh K, Crawford D, Salmon J, Jackson M, Campbell KInt J: Associations between family circumstance and weight status of Australian children. Pediatr Obes 2007; 2: 86–96.

32 Dwyer J, Stone E, Yang M et al: Prevalence of marked over-weight and obesity in a multiethnic pediatric population: findings from the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health (CATCH) study. J Am Diet Assoc 2000; 100: 1149–1156.

33 Francis CC, Bope AA, MaWhinney S, Czajka-Narins D, Alford BB: Body composition, dietary intake, and energy expenditure in nonobese, prepubertal children of obese and nonobese biological mothers. J Am Diet Assoc 1999; 99: 58–65.

34 Hurrelmann K, Laaser U: Health sciences as an interdisciplinary challenge: the development of a new scientific field. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 1995; 8: 195–214.

35 St Leger L: What’s the place of schools in promoting health? Are we too optimistic? Health Promot Int 2004; 19: 405–408.

36 Viner RM, Barker M: Young people’s health: the need for action. BMJ 2005; 16(330): 901–903.

37 Norton I, Moore S, Fryer P: Understanding food structuring and breakdown: engineering approaches to obesity. Obes Rev 2007; 8(Suppl. 1): 83–88.

38 Kain J, Uauy R, Albala Vio F, Cerda R, Leyton B: School-based obesity prevention in Chilean primary school children: methodology and evaluation of a controlled study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004; 28: 483–493.

39 Gao Y, Griffiths S, Chan E: Community-based interventions to reduce overweight and obesity in China: a systematic review of the Chinese and English literature. J Public Health 2007; 11: 1–13.

40 Cameron N: The biology of growth. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program 2008; 61: 1–19.

41 Rush E, Plank L, Chandu V et al: Body size, body composition, and fat distribution: a comparison of young New Zealand men of European, Pacific Island, and Asian Indian ethnicities. N Z Med J 2004; 117: U1203.

42 Nooyens A, Koppes L, Visscher T et al: Adolescent skinfold thickness is a better predictor of high body fatness in adults than is body mass index: the Amsterdam Growth and Health Longitudinal Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 85: 1533–1539.

43 Stewart-Brown S: Promoting health in children and young people: identifying priorities. J R Soc Health 2005; 125: 61–62.

44 Thomas R, Perera R: School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 3 (Art. No. CD001293).

45 Foxcroft D, Ireland D, Lister-Sharp D, Lowe G, Breen R: Primary prevention for alcohol misuse in young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002; 3 (Art. No. CD003024).

46 Lister-Sharp D, Chapman S, Stewart-Brown S, Sowden A: Health promoting schools and health promotion in schools: two systematic reviews. Health Technol Assess 1999; 3: 1–207.

47 World Health Organization: The Bangkok Charter for health promotion in a globalized world. Health Promot J Austr 2005; 16: 168–171.

48 Bolam B, Murphy S, Gleeson K: Individualization and inequalities in health: a qualitative study of class identity and health. Soc Sci Med 2004; 59: 1355–1365.

49 Stewart-Brown SL: What is the evidence on school health promotion in improving health or preventing disease and, specifically what is the effectiveness of the health promoting schools approach. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for the Europe Health Evidence Network (HEN). 2006.

50 Hawe P, Shiell A: Use of evidence to expose the unequal distribution of problems and the unequal distribution of solutions. Eur J Public Health 2007; 17: 413.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree