Summary and recommendations for practice

- There are complex evidence needs for preventing childhood obesity.

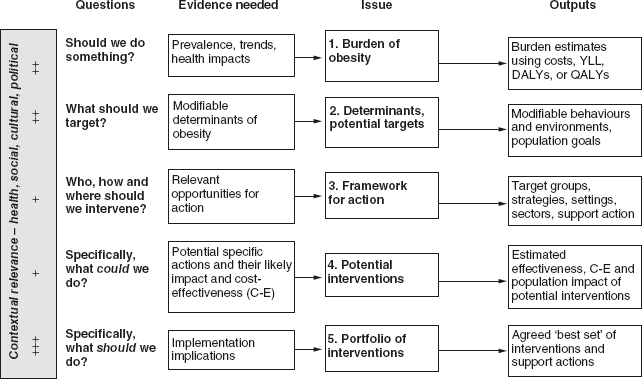

- The International Obesity Taskforce has developed an evidence framework for obesity prevention and it poses five sets of questions that need different types of evidence to answer them.

- The evidence on the burden of obesity is sufficient to warrant action and the evidence on the determinants of obesity is also informative on what to do.

- The priority target groups [who] are mainly children and adolescents and high-risk adults, and schools are the favoured setting [where] although multiple settings are preferable. The strategies [how] also need to be multi-pronged with communications, programs and policies being the main approaches.

- The evidence on effective interventions is quite limited although it is growing rapidly, especially for whole-of-community intervention approaches.

- A priority setting process needs to use all available evidence to define a portfolio of promising interventions.

- There are still very large evidence gaps from too few “solution-oriented” studies.

There are enormous evidence needs in obesity prevention but the current evidence base is very narrow in some areas such as intervention effectiveness and cost–effectiveness. In addition, the paradigm of “evidence-based public health” is emerging from its roots in evidence-based medicine and this brings with it the challenge of the complexity of the evidence needed for public health interventions, which are not as susceptible to randomized, controlled trials as clinical interventions.

In an effort to clarify the role of evidence in obesity prevention, the International Obesity Taskforce (IOTF) published a framework1 that identified the key questions to be answered, the types of evidence needed and outputs produced, and the role of contextual factors (Figure 6.1). In the process of building this framework, a number of general concepts and specific issues emerged about evidence as it applies to obesity prevention.

Definitions and hierarchies of evidence

Evidence, in its widest sense, is information that can provide a level of certainty about the truth of a proposition.2 This is a very broad definition, more along the lines of the legal, rather than the medical, concept of evidence and implies that this breadth of information is important and valid for decision making. For the purposes of addressing the questions on obesity prevention, the IOTF framework grouped evidence into observational, experimental, extrapolated and experience-based sources of evidence and information.1 Examples of these are outlined in Table 6.1.3

Table 6.1 Types of evidence and information relevant to obesity prevention.3

| Type of evidence or information | Description |

| Observational | |

| Observational epidemiology | Epidemiological studies that do not involve interventions but may involve comparisons of exposed and non-exposed individuals, for example, cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort studies |

| Monitoring and surveillance | Population-level data that are collected on a regular basis to provide time series information, for example, mortality and morbidity rates, food supply data, car and TV ownership, birth weights and infant anthropometry |

| Experimental | |

| Experimental studies | Intervention studies where the investigator has control over the allocations and/or timings of interventions, for example, randomized controlled trials, or non-randomized trials in individuals, settings, or whole communities |

| Program/policy evaluation | Assessment of whether a program or policy meets both its overall aims (outcome) and specific objectives (impacts) and how the inputs and implementation experiences resulted in those changes (process) |

| Extrapolated | |

| Effectiveness analyses | Modeled estimates of the likely effectiveness of an intervention that incorporate data or estimates of the program efficacy, program uptake, and (for population effectiveness) population reach |

| Economic analyses | Modeled estimates that incorporate costs (and benefits), for example, intervention costs, cost–effectiveness, or cost–utility |

| Indirect (or assumed) evidence | Information that strongly suggests that the evidence exists, for example, a high and continued investment in food advertising is indirect evidence that there is positive (but proprietary) evidence that the food advertising increases the sales of those products and/or product categories |

| Experience | |

| Parallel evidence | Evidence of intervention effectiveness for another public health issue using similar strategies, for example, the role of social marketing or policies or curriculum programs or financial factors on changing health-related behaviors such as smoking, speeding, sun exposure, or dietary intake. It also includes evidence about the effectiveness of multiple strategies to influence behaviors in a sustainable way, for example, health-promoting schools approach, comprehensive tobacco control programs, or coordinated road toll reduction campaigns. |

| Theory and program logic | The rationale and described pathways of effect based on theory and experience, for example, linking changes in policy to changes in behaviours and energy balance, or ascribing higher levels of certainty of effect with policy strategies like regulation and pricing compared with other strategies such as education |

| Informed opinion | The considered opinion of experts in a particular field, for example, scientists able to peer review and interpret the scientific literature, or practitioners, stakeholders, and policy-makers able to inform judgments on implementation issues and modeling assumptions (incorporates “expert” and “lay knowledge”) |

Each type of evidence has its own strengths and weaknesses. Each can be judged on its ability to contribute to answering the question at hand. In practice, there is wide variation in the quantity and quality of information available in respect of different settings, approaches and target groups for interventions to prevent obesity. There is virtually no evidence concerning the potential effects on obesity of altering social and economic policies, such as agricultural production policies or food pricing policies, while much more evidence is available on localized attempts to influence the consumer through educational and program-based approaches.

Traditional hierarchies of evidence are based on rankings of internal validity (certainty of study conclusions). These tended to be less valuable in the IOTF framework because of the tension between internal validity and the need for external validity (applicability of study findings). The importance of context on evidence and the need for external validity is greater in some areas than others (left-hand bar in Figure 6.1). It is especially important at the priority setting stage (issue 5), and this is where the informed opinions of stakeholders is paramount.

Modeled estimates of effectiveness and informed stakeholder opinion also become important sources of information where the empirical evidence is complex, patchy and needs to be applied to different contexts. This means that assumptions and decisions must be made explicit and transparent. The acceptance of modeled estimates of effectiveness and informed opinion in the absence of empirical evidence means an acceptance of the best evidence available not just the best evidence possible (as occurred in systematic reviews with strict inclusion criteria).

Evidence on the burden and determinants of obesity

These are the first two issues in the IOTF framework (Figure 6.1). In general, the size and nature of the obesity epidemic has been well enough characterized to have created the case for action. Of course, many gaps and debates still remain, such as the prevalence and trends in poorer countries, the psycho-social impacts of obesity in children, and the effect of the epidemic on life expectancy.

Evidence on the determinants of obesity is very strong in most areas, although to date, most of it is focused on the more proximal biological and behavioral determinants rather than the more distal, but very important, social and environmental determinants. One poorly researched but very obvious set of determinants are the socio-cultural attitudes, beliefs, values and perceptions that may explain the very large differences in obesity prevalence rates seen across different cultures. These socio-cultural determinants may help to explain why both rich and poor countries have obesity prevalence rates in women of less than 5% (e.g., India, China, Yemen, Ethiopia, Japan and Korea) and greater than 40% (e.g., Samoa, Tonga, Qatar and Saudi Arabia).4

Knowing a lot about the determinants of obesity should help to guide interventions but, as Robinson and Sirard point out,5 “problem-oriented” evidence (what is to blame?) is often quite different to “solution-oriented” evidence (what to do?) It is the solution evidence that decision makers are urgently seeking and it is this evidence that is currently lacking.

Opportunities for action—who, where, how?

This is the third issue on the IOTF framework (Figure 6.1). Many countries have now created strategic plans for action on obesity either as an issue by itself or as part of promoting physical activity or health eating or reducing chronic diseases. Classic frameworks for health promotion specify “who” in terms of target groups (e.g., children, adolescents, pregnant women, minority ethnic groups, those on low incomes), “where” in terms of settings or sectors (e.g., schools, the commercial sector, the health sector), and “how” approaches or strategies (e.g., school education, community development, the use of mass media, environmental change, policy and infrastructure change).3 These issues are addressed in other chapters in this book but a few brief comments about target groups are warranted.

A potential limitation of identifying target groups is that they become too much the focus of the action (e.g., by encouraging them to make the healthy choices) rather than the players that influence the environments that determine those behaviors (those who can make the healthy choices easier for the target group). In this respect, the definition of target groups may need to be widened to include the providers of the determinants of health, such as the providers of health information—the health services, schools, the media, commercial producers—and widened still further to include those that set the policies which shape access to healthy lifestyles through, for example, pricing, distribution and marketing. In this sense, target groups may include shareholders in companies, professional groups, policy-makers and public opinion leaders, including politicians.

Prevention strategies targeting adults make economic sense (if they work) because the consequences of obesity occurring in middle aged and older adults generate economic costs—especially through Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.6 Adults, especially those with other existing risk factors, are at high absolute risk of these diseases; therefore, they have the potential for high absolute gains. In addition, there is now very strong efficacy evidence that individual lifestyle interventions in high-risk adults prevent diabetes and heart disease.7,8 However, despite this evidence and logic, children have risen as the priority target group for most action on obesity and this has occurred for a number of reasons—some based on evidence, some based on societal principles, and some based on practicalities.

Excess weight, once gained, is hard to lose but children who are overweight do have a chance to “grow into” their weight. Children’s behaviors are also much more environmentally dependent than adults’ behaviors and most of the evidence on obesity prevention has been in children. However, far more powerful than the sum of the evidence are two other drivers of children as the priority target group: societal protection of children and access for interventions—especially through schools. Policy-makers have been especially sensitive to children because society has an obligation to protect them from ill-health. For adults, the societal obligation shifts towards protecting personal choice—even if that choice is for unhealthy foods and physical inactivity.

Effectiveness of potential interventions

This is the fourth issue in the IOTF framework (Figure 6.1) and asks: “What are the potential, specific interventions and what is the evidence for their effectiveness?” This question is covered in many other chapters in this book and only some overview comments are be made here.

In general, it is possible to generate quite long lists of potential interventions to help prevent childhood obesity, although some of the intervention areas, such as improved parenting skills, are more readily identified in generalities than in specific interventions. However, adding effectiveness evidence to any more than a few of them is very difficult because of the absence of intervention studie. For the interventions that have been studied, most concern primary school children, most are in school settings, most are short term, most are not sustainable, and most have shown relatively modest effects on anthropometry (although they were often able to show improvements in eating and/or physical activity). The number of reviews in the area is starting to outnumber the number of studies.9–29

As interventions move towards more whole-of-community interventions, there is an increased complexity in the study design, the interventions and the evaluations, although some positive results are starting to emerge from these studies, which is very encouraging.30–32 More sophisticated multi-level modeling will be needed to tease out intervention effects in these more complex interventions.

For policy-makers considering strategy options, the distinction between effectiveness and cost–effectiveness is critical. If a policy objective is to be pursued with no limitation on spending, then effectiveness (the beneficial effect of a strategy in practice) is the primary consideration. But when cost limitations apply (as they inevitably do), an evaluation of cost–effectiveness is essential if rational decisions are to be made.33

A remarkable feature of the evaluations and systematic reviews of interventions described above is that they rarely mention the costs of the various programs they examine, and make no estimates of cost–effectiveness. For child obesity prevention, only one study has explicitly examined the costs of an intervention program, the US Planet Health Program.34 Planet Health’s estimated cost–effectiveness ratio gives a value of $4305 per quality-adjusted life year gained, which compares favorably with interventions such as the treatment of hypertension, low-cholesterol-diet therapies, some diabetes screening programs and treatments, and adult exercise programs.35

Creating a portfolio of interventions

The evidence for obesity prevention covered thus far has shown: a substantial burden to warrant action; sufficient understanding of the determinants to know what to target; a determination of the priority target populations (who), the best settings to access (where), and the most appropriate strategies to use (how), and; a review of the literature about what has been shown to work, or not work. The final challenge in the IOTF framework (prior to actually implementing and evaluating the work) is to create the “portfolio” of interventions to be implemented. And what a challenge in priority setting it is, because the aim of intervention selection is:

to agree upon a balanced portfolio of specific, promising interventions to reduce the burden of obesity and improve health and quality of life within the available capacity to do so.

“Agreement” infers a process with decision makers coming to a joint understanding. “Balanced portfolio” means a balance of content (both nutrition and physical activity), settings (not all school-based), strategies (policies, programs, communications), and target groups (whole population, high risk). Interventions need to be “specific” (not “promote healthy eating”) and “promising” rather than proven. The analogy of choosing a balance of products (shares, property, bonds) to create portfolio of financial investments has been used by Hawe and Shiell36 to conceptualize appropriate investment in health. The best investments are the safe, high-return ones (i.e,. high level of evidence, high population impact) but, inevitably, the choices come down to including some safe, lower-return investments and some higher-risk (i.e., less certainty), potentially higher-return investments while excluding the high-risk, low-return ones. The IOTF framework1 applies this investment concept to obesity prevention and presents a “promise table”, which is a grid of certainty (strength of evidence) versus return (population impact) into which interventions can be placed according to their credentials.

The other key concepts in the priority setting aim are that the interventions reduce the “burden of obesity” and “improve health and quality of life”. These issues are particularly important for obesity prevention because many of the interventions (healthier eating and physical activity) have their own independent effects on health and some interventions have the potential to do harm (such as increase stigmatization and teasing) or increase health inequalities. Fitting the plan of action to the available capacity to achieve it is especially challenging at the community level where the level of health promotion funding is usually very low and the enthusiasm for doing something is usually very high.

Practice-based evidence

Given the challenging aim of intervention selection, how can this be achieved and what role does (or should) evidence play in the process? Certainly, the evidence of effectiveness is not sufficient by itself to guide appropriate decision making, and, indeed, true evidence-based policy-making is probably quite rare.37 Some major policy decisions are made on the basis of extremely little evidence despite high costs (such as military interventions). A helpful concept to apply is that of “practice/policy-based evidence”.37 Evidence-based practice/policy starts in the library, assesses what has been published and then takes that intelligence to the policy-maker or practitioner to consider for implementation. Practice/policy-based evidence starts at the table with the practitioner or policy-maker and assesses what could be implemented with the ideas coming from many sources: what is already happening here, what is happening elsewhere, what the literature shows, what the politicians want to implement and so on. Then some technical estimates are made using the best evidence available and these are brought back to the table to inform the priority setting. Two examples of this are given below.

Evidence and priority setting processes

The ACE-Obesity project (Assessing Cost–Effectiveness of Obesity Interventions) was funded by the Victorian government in Australia to inform it on the best investments for reducing childhood obesity nationally.38 The ACE approach (which is also covered in Chapter 20) included extensive economic analyses around agreed, specified interventions to reduce childhood obesity at a state or national level, plus a process that engaged key stakeholders in first selecting the interventions for analysis and then, second, providing judgements on the modeling assumptions and a number of “second stage filters” (strength of evidence, feasibility, sustainability, acceptability, effects on equity, other positive or negative effects). The definition of evidence was wide and all assumptions in the modeling had to be explicit and have in-built uncertainty estimates. In this way, policies (such as banning food advertisements to children), programs (such as active transport to school) and services (such as gastric banding for very obese teenagers) which lacked trial evidence could still be modeled. The outputs were estimates of total cost, population health gains (BMI units saved or disability-adjusted life years [DALY] saved), cost–effectiveness ($/BMI saved, $/DALY saved), and plus the second stage filter judgements.

The same challenges of defining what could be done and then undertaking a priority setting process to determine what should be done apply at the community level as much as they apply at a state or national level. Similar principles to ACE-Obesity, but a simplified process, were applied in the formative stages of six demonstration projects in Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific.39 The details of this process (the ANGELO Process) are covered in Chapter 26.

There are some major gaps in the evidence base need for sound judgements on preventing childhood obesity. The box outlines some of the key areas of evidence need which have been updated from a WHO meeting on Childhood Obesity in Kobe, Japan in 2005.40

Evidence needs for preventing obesity in children and adolescents

- All interventions should include process evaluation measures, and provide resource and cost estimates. Evaluation can include impact on other parties, such as parents and siblings.

- Interventions using comparison groups should be explicit about what the comparison group experiences. Phrases like “normal care” or “normal curriculum” or “standard school PE classes” are not helpful, especially if normal practices have been changing over the years.

- There is a need for more interventions looking into the needs of specific sub-populations, including immigrant groups, low-income groups, and specific ethnic and cultural groups.

- There is a shortage of long-term programs evaluating and monitoring interventions. Long-term outcomes could include changes in knowledge and attitudes, behaviors (diet and physical activity) and adiposity outcomes.

- New approaches to interventions, including prospective meta-analyses, should be considered.

- Community-based demonstration programs can be used to generate evidence, gain experience, develop capacity and maintain momentum.

- There is a need for an international agency to encourage networking of community-based interventions, support methods of evaluation and assist in the analysis of the cost–effectiveness of initiatives.

- There is insufficient evidence on the impacts of cultural values, beliefs, expectations and attitudes around food, physical activity and body size perception to inform interventions in the high-risk ethnic groups.

- Better evidence is needed about the most effective ways of feeding BMI information back to parents and for health professionals to raise the issue of their children’s weight with parent.

- Evidence on the most effective and cost-effective monitoring systems and their impacts on national and community actions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree