Summary

- The childhood obesity epidemic demands a concerted prevention effort from governments, international organizations, the private sector and civil society.

- A life-course approach to preventing childhood obesity provides multiple opportunities for intervention and many childhood settings offer opportunities for access to children and parents.

- Government policies are needed to provide the backbone for health promotion activities.

- International agencies and multinational food companies have critical supporting roles to play.

- Marketing of unhealthy foods to children is a multi-billion dollar commercial enterprise and these practices severely undermine the efforts of parents, governments and health and education professionals to provide a healthy environment for children.

The rising prevalence of childhood obesity in most populations around the world is a matter of grave concern because the physical, psychological and social consequences of obesity in childhood are substantial.1 The increase in the prevalence of obesity has been accompanied by a more rapid increase in the severity of obesity with more children becoming severely obese, indicating that obesity-related medical conditions will rise at least as rapidly as the overall obesity prevalence rate. Furthermore, as these children carry that risk of excess weight into adulthood, the impact of obesity on the management of chronic disease and disability will continue to grow as the epidemic gains momentum.2 The consequences of the obesity burden and related diseases include not only the known health consequences but also lost educational opportunity and lost economic contribution from the lost days of employment by an older adolescent, or by a parent or carer in the family if the child requires medical attention. Furthermore, there are many intangible costs such as the psycho-social consequences of obesity.1

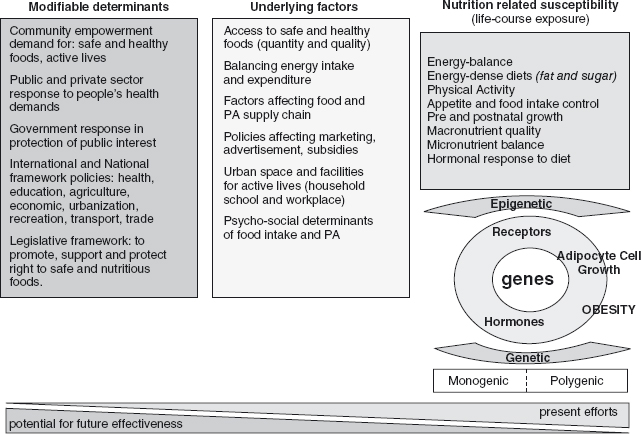

Since the early 1990s, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children has increased in virtually every country of the world: in some it has doubled and in others it has tripled.3 It is now recognized that there are many societal and environmental drivers of unhealthy weight gain4,5 and yet most of the research efforts are directed at the individual level, particularly the genetic level, and most of the current prevention efforts center on education and social marketing approaches rather than underlying determinants. This is shown schematically in Figure 3.1. This chapter provides an overview of some of the approaches to reducing the rapidly increasing epidemic of childhood obesity and calls for multiple interventions across the life course backed by a much greater focus on reversing some of the underlying drivers of the epidemic. We also examine one of the critical drivers of childhood obesity: food marketing that targets children.

Figure 3.1 The hierarchy of determinants of childhood obesity from basic societal determinants (which have the greatest potential for prevention efforts) to individual and genetic predisposition (which is where the greatest efforts are currently based).

A life-course approach to obesity prevention

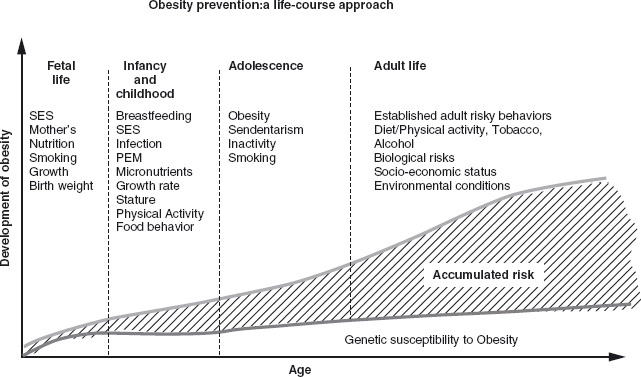

The concept that obesity should be prevented using a life-course approach is relatively new. The old concept that children would outgrow overweight and obesity has been abandoned based on the currently available data which show that as obesity prevalence rises the tracking of increased adiposity into adulthood becomes stronger and more clearly defined.6 The evidence indicates that the time to consider obesity and chronic disease prevention is from early life and continues throughout every stage of the life course, Figure 3.2 offers a graphic depiction of this concept.

Figure 3.2 The life-course approach to obesity prevention considers age specific actions at each stage of the life course, the objective of these actions is to ameliorate the burden of obesity that is preventable by diet and physical activity interventions.

Preconception This is an important time to ensure, if possible, that maternal body mass index (BMI) is normal (i.e., between 18.5 and 25 kg/m2) and that micronutrient status is normal (i.e., any anemia is corrected and folate intake is adequate through adequate diet, fortified foods or supplements). Monitoring maternal weight gain is important to reduce the risk of low birth weight (<2.5 kg) as well as macrosomia (birth weight >4.0 kg). The relationship between birth weight and obesity is that of an open J-shaped curved: that is, both low birth weight and high birth weight are associated with a higher risk of later obesity. While the mechanisms by which intrauterine undernutrition or overnutrition predisposes to later unhealthy weight gain are beginning to be elucidated,7 the key message is that we should change what is considered good nutrition during infancy, from a focus on weight gain to one where linear growth and the proportionality of weight relative to length are truly important.

Infants and young children The main preventive strategies for these groups are to: promote and support the practice of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life as the preferred mode of feeding; avoiding the use of added sugars and starches when feeding artificial formula, considering that flow of milk from the bottle is faster than from the breast, so it is easier to provide excess energy; instructing mothers to accept their child’s ability to regulate energy intake rather than feeding until the plate is empty; and assuring the appropriate micronutrient intake needed to promote optimal linear growth.

Older children and adolescents The main preventive strategies in these age groups are to: promote an active lifestyle, limit television viewing, promote the intake of fruits and vegetables; restrict the intake of energy-dense, micronutrient-poor foods (e.g., packaged snacks); restrict the intake of sugar-sweetened soft drinks. Additional measures to support these behavioral approaches include: modifying the environment to enhance physical activity in schools and communities; creating more opportunities for family interaction (e.g., eating family meals); limiting the exposure to aggressive marketing practices of energy-dense, micronutrient-poor foods; and providing the necessary information and skills to make better food choices. In lower income countries, special attention should be given to avoidance of overfeeding stunted population groups. Nutrition programmes designed to control or prevent undernutrition need to assess stature in combination with weight to prevent providing excess energy to children of low weight-for-age but normal weight-for-height.8,9 In countries undergoing rapid growth and demographic transition, and as populations become more sedentary and able to access energy-dense foods, there is a need to maintain the healthy components of traditional diets (e.g., high intake of vegetables, fruits and non-starch polysaccharides).10

Education provided to parents from disadvantaged communities that are food insecure should stress that overweight and obesity do not represent good health. Low-income groups globally and populations in countries in economic transition often replace traditional micronutrient-rich foods by heavily marketed, sugar-sweetened beverages (such as soft drinks) and energy-dense fatty, salty and sugary foods.10

These trends, coupled with reduced physical activity, are associated with the rising prevalence of obesity. Strategies are needed to improve the quality of diets by increasing the consumption of fruits and vegetables, in addition to increasing physical activity, to stem the epidemic of obesity and associated diseases.

Linking community, national and global approaches

The opportunities for action can be viewed not only by life stages but also by the settings and sectors where specific action can take place. While these are explored in detail in the other chapters in this book, this section provides an overview of the major options in relation to specific childhood settings and the government policies and sector changes which are essential to support healthy eating and physical activity. Food marketing to children is dealt with separately because it is such an important policy strategy to support parents and to provide a healthier environment for children.

Communities and settings

Homes and families

The home and family environment has by far the most powerful influence on children and many aspects of parenting and home life have been shown to be associated with unhealthy weight gain in children and adolescents.11,12 However, when it comes to health promotion, access to parents is relatively limited with the main options being through social marketing directly and through childhood and health-care settings.

Preschool settings

Health promotion efforts in preschool settings (nurseries, child-care kindergarten etc.) provide essential access to young families, especially first-time parents who are in a rapid learning period about caring for children’s food and activity needs. Preventive services should ensure that the needs of nutritionally-at-risk infants and children are met, paying special attention to linear growth of pre-term and/or low birth weight infants, and that interventions are monitored to avoid excess weight relative to length gain increases the risk of obesity in later life. Parents should be encouraged to actively play and interact with their children, starting from infancy, to promote active living and motor development.

Nurseries and kindergartens should ensure that they do not restrict physical activity and promote sedentary habits during the growing years. Children in nurseries should be involved in active play for at least one hour a day, so appropriate staffing and physical facilities for active and safe play should be a requirement for nurseries caring for young children.

Schools

Schools represent a unique opportunity for obesity prevention. They can serve to exemplify the preferred approaches to good nutrition and active living, and their practices should set an example not only for the students but also for their families. A coherent, comprehensive “whole school” approach (children, parents and all staff including food services) to health promotion (active living and healthy diets) is needed because it is more likely to be sustainable, and there are broader benefits for the child (e.g., improved educational, social and self-esteem outcomes) and the community at large. Funding of schools including sports and athletic facilities needs to be independent of commercial sources to prevent pressures that counter the ethos of obesity prevention. Raising funds for school programmes by sponsorships from unhealthy snacks and sugary drinks manufacturers sends the wrong message to both pupils and the larger school community. Teachers may need additional training in health promotion, including personal advice in terms of healthy weight and active living, since they are role models for the pupils they teach. Further training of staff may be needed to ensure obese children are not stigmatized or bullied by others in the school. Consistent policies are needed to ensure the nutritional value of foods made available in schools. Physical education is also a vital part of the curriculum in all grades. Chapters 10, 11 and 30 on the evidence for school-based interventions and working in schools provide much more detail on this crucial setting for childhood obesity prevention.

Health care services

Health care facilities need to provide a range of preventive services and health promoting activities, and should liaise with schools and community services to ensure that their messages are given prominence. Health care staff also have a role in monitoring children’s growth to recognize early signs of “mis-nourishment”, including stunting and overweight, and to provide appropriate responses. The contacts between parents and the maternal/child health nurses are especially important “learning moments” and should be utilised to encourage breastfeeding and teach parents about appropriate growth trajectories and feeding practices for their children. The evidence on effective primary care management is very limited (as outlined in Chapter 12) and many of the existing structures in primary care, especially the funding structures that dictate the short consultation periods, conspire against this setting being used to its full potential (see Chapter 31).

Community-wide approaches

Enabling environments must encompass all communities and must also operate within a given community, affecting transport policies, urban design policies and access to healthy diets. Community-wide approaches play an important role in providing the broader approach, and these are covered in more detail in Chapters 7, 26, 27. However, it is worth emphasizing the need to ensure adequate access to healthy foods for low-income families. This may require programs and policies to ensure that healthy food is more readily available, affordable and better promoted than the unhealthy alternatives.

National policies

While there are several key players in obesity prevention (governments, international organizations, the private sector and civil society/non-governmental organizations), governments need to take the lead and to drive the policy changes. Each country should select a mix of promising policies and actions that are in accord with national capabilities, laws and economic realities.13 Ministries of health have a crucial convening role in bringing together other ministries that are needed for effective policy design and implementation. However, it is important to realize that while health usually takes a large slice of national budget, ministers of health are not usually the most powerful members of cabinet. Governments need to work together with the private sector, health professional bodies, consumer groups, academics, the research community and other non-governmental bodies if sustained progress is to occur.

National policies and programs should explicitly address equality and diminish disparities by focusing on the needs of the more disadvantaged communities and population groups. Furthermore, since women generally make decisions about household nutrition, strategies need to be gender sensitive. Continued support for the full implementation of the WHO-UNICEF Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes is vital in all countries. Recommendations for local and central governments are delineated in the WHO Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health (DPAS)14 and, in addition to the specific measures to address childhood obesity, they also have a fundamental role in providing the support strategies for effective obesity prevention, as shown in the box below.

Support functions for governments in addition to specific obesity prevention interventions

- Monitoring programs on outcomes (obesity), and determinants (e.g., behaviors and environments) should report to a parliamentary scrutiny committee or an “obesity observatory”.

- Coordination to ensure cross-departmental, cross-sectoral polices can be implemented and these should managed centrally by government but monitored by a separate agency.

- Capacity should be built at national and at local levels, through training programs and other support structures and funding.

- State support for commerce (e.g. food enterprises, agricultural enterprises) should include health criteria.

- Political donations from food companies should be restricted.

- Access to and affordability of fruits and vegetables should be improved, especially for low-income and disadvantaged population groups.

- National governments should support WHO moves to ensure that all UN agencies have policies that are consistent with the Global Strategy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree