Summary and recommendations for practice

Key elements in converting academic analyses into policy implementation

- Prepare groundwork by producing coherent evidence, reports and briefing papers, to promote public and political awareness.

- Develop a broad consensus among eminent scientific/medical leaders; anticipate poor support from many clinicians with political ambitions and little understanding of public policies.

- Engage openly with the media; focus on opinion leaders. Repeatedly explain the issues willingly and patiently.

- Be ready for confrontation from opposing viewpoints and prepare reasoned responses developing new work to answer the challenges.

- Create a movement by engaging different societal and academic groups with established political connections to agree the main consensus not the detail.

- Remember that political change takes time and depends on a crisis or incessant vocal public and expert lobbying.

- Focus on finance—health ministries are weak: other ministers or the prime minister make decisions affecting other sectors, based on economic arguments and political pressure.

Public health initiatives require a sophisticated understanding, not only of medical concerns, but also of political issues in order to appreciate why some initiatives succeed and others do not. The national response to health needs is often delayed. Examples of this delay include the slow reaction to the HIV contamination of recombinant factor 8 plasma transfusions for hemophiliacs, and the extremely slow response to the emergence of the HIV/Aids epidemic. Similarly, the need to take action in response to the huge death and disability rates from coronary heart disease (CHD) was ignored for years by many governments, allegedly on the grounds that the scientific and medical communities could not agree that a clear link existed between CHD and high blood cholesterol levels, induced by saturated fat intakes, high blood pressure and smoking. Even if this could be proved, inaction was justified by the view that it was the individual’s own responsibility to change his or her diet and lifestyle. The government’s role was seen as simply providing health promotion messages to enable consumers to make “informed” food choices. The huge agricultural and food industries recognized that they had to show concern for their customers and a vague health educational message suited their interests because their profits often depended on continuing to sell high saturated fat-filled products.

Given that it has taken several decades to see major international initiatives even on tobacco, how do we create the political will for action to be taken? We conclude that the triggers owe less to a clear understanding of the science, or even evidence for the benefits of change, than to a political need to respond publicly to an issue of pressing public concern. We illustrate this from our own experience of political responses to UK and global health concerns since the mid-1970s.

The contrasts in the responses to food safety and diet-related disease issues

The response to the risks of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) is instructive. Decisive action was resisted initially as there was great uncertainty about a little understood infective agent, a prion, and fairly clear evidence already that there were species barriers in the susceptibility of different species to prions. So the UK Minister of Agriculture repeatedly denied that there was any danger from eating BSE-infected meat products, for example, from some types of fast food. However, 10 years after one of the authors (WPTJ) was alerted confidentially to the development of the BSE outbreak in cattle, there was suddenly a cabinet crisis in 1996 when the head of the Expert BSE group, Professor John Pattison, insisted throughout several hours of grilling by the Prime Minister and his senior colleagues that the first 10 cases of a new strain of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (new variant CJD) must be assumed to arise from infected beef (personal communication). Quite dramatic moves on BSE were made by the UK Prime Minister within 24 hours because at that stage it was recognized that the agent had the potential to infect huge numbers of the population (numbered then at up to 8 million) and this would affect individuals randomly with a ghastly and inevitably fatal disease. Scientific guesswork, the presumed manipulation of evidence by ministers and the political pressure to protect the long-term interests of the farming and food sectors, magnified the alarm of the public, media, some sections of the medical profession and ministers themselves. So this was a major crisis in political, economic and social terms. The beef bans, changes in farming practice and removal of beef export licences that followed cost the UK tax payer over £6 billion and the ensuing changes in Europe cost far more.

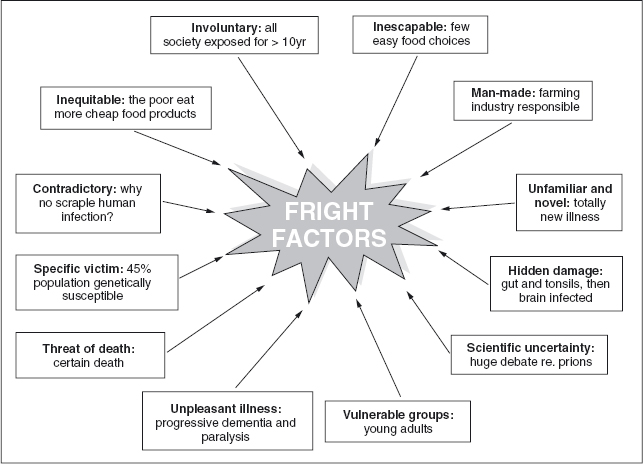

Figure 25.1 shows the array of major factors that influence public thinking on risk in general and how these factors relate to the public’s perception of the risks of BSE.

Figure 25.1 Public Perception of Risk (with examples from bovine spongiform encephalopathy risk). Key factors in the huge public response to the identification of human vCJD, acquired from Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy in cattle, included the fear of widespread exposure through unknown sources to an indiscriminate agent which induced a terrifying and untreatable illness and certain death, particularly among the young.

The contrast with such issues as obesity, diabetes, or coronary heart disease (CHD) is striking. Yet the draconian measures for handling BSE were taken on far less evidence than that which underlay the dietary basis for the hundreds of thousands of deaths from CHD and the contrast with the governmental effort to prevent CHD is striking. No country has spontaneously introduced major strategic changes in food policies on the basis of analyses of chronic diseases and their risk factors by government expert committees.1 CHD is still the biggest contributor to deaths and CHD and cancers in the UK continue to account for more than two thirds of preventable UK deaths, that is, in those under 75 years. Yet the only issue which resonates in political circles is the higher death rate among the poorer classes and the failure to treat cases promptly and adequately.

The problem is that it is almost universally assumed that diet depends on an individual’s choice and that while the consequences are hazardous, heart attacks and strokes occur later in life and “one has to die of something”. Type 2 diabetes was seen as an unfortunate condition in the elderly and really linked to a family history of susceptibility. The dreaded risks of cancer were not linked to diet, but to pesticides and chemical carcinogens, which governments still try to understand and limit by engaging large groups of experts. Thus, the public health response to the post-war epidemic of CHD in Europe and North America has depended on groups of cardiologists initiating public debates and proposing changes. This, in turn, has stimulated the food industry to respond by producing lower-fat milks, butter and spreads, and changes in the fatty acid content of foods, thereby providing themselves with excellent marketing material! In every case where political action has been taken there has been political pressure from highly vocal individuals or groups within the academic community or civil society. Furthermore, despite the preventability of Type 2 diabetes, until very recently no effort had been made by doctors, or even by the specialist interest groups, to address its prevention. The huge charitable organizations that fund research on heart disease, stroke, diabetes and cancer, pump millions of dollars into basic research and improved treatment, but support almost nothing in prevention. Indeed, many of the heart foundations and cancer charities have either simply paid lip service to the preventive issue or even attacked preventive initiatives because they were based on crude measures or could demonstrate no “proof” of their effectiveness.

Background to the obesity crisis: the reasons for its early neglect

Despite the original inclusion of obesity in the International Classification of Diseases in 1948, obesity remains a condition that even some in the medical professions fail to recognize as a disease. Yet warnings about an impending obesity epidemic came during the 1970s in the USA, with “Fogerty” conferences,2 and in the UK with government/Medical Research Council analyses of the disease and disability likely to be induced by the growing epidemic. The UK report, with remarkable prescience, did warn in 1976: “We are unanimous in our belief that obesity is a hazard to health and a detriment to well-being. It is common enough to constitute one of the most important medical and public health problems of our time.”3

By 1983 another UK report4 on obesity called for public health policy changes at a time when adult obesity prevalence stood at 7%. As with the similar Royal College of Physicians reports on smoking5 and on cardiovascular disease by Shaper,6 these were all hailed by the College Council as being of immense political and policy importance, but had no effect because they were not locked into the political process. There was also little media coverage and lobbying by academics and civil society groups.

Putting obesity and chronic disease on WHO’s agenda

The highly publicized report in the UK from the National Advisory Committee on Nutrition Education in 19837 led to the WHO European Regional Office asking for a major new assessment throughout Eastern, Central and Western Europe of nutritional issues, chronic diseases, (including obesity) and their prevention. This in turn led to the first global WHO/FAO report in 1990, which considered both under-nutrition and chronic diseases in a coherent global context.8 This set out far-reaching recommendations which, almost two decades later, remain the basis of widely accepted, but largely unattained, public health goals. These reports were seen by WHO as important, were referred to in major committees of ministers and were highlighted in global academic conferences. Yet despite this public recognition, public health actions were still not instigated, even though there was a clear specification of different levels of initiative required by international, national and local communities.

In fact, both WHO and FAO faced a barrage of lobbying and overt opposition from global sugar interests which dominated the US and European food industries’ attitudes. The US government was persuaded by lobbyists to try to block the report’s acceptance by WHO, but it failed and the scientific community endorsed the global report’s new thinking at the International Congress of Nutrition in 1992.9

Over a period of almost 20 years, there have been numerous reports on nutritional aspects of health with, in the 1990s, specific recommendations on obesity, but again without any effect. The medical profession was then largely responsible for specifying that obesity was simply a risk factor induced by people who needed to alter their personal habits. The food industry was also totally entrenched in promoting its products and had excellent government connections, strengthened by providing financial support to political parties. As a consequence, slimming clubs flourished and tens of millions of adults have attempted repeatedly to slim, with articles on the subject guaranteeing an avid readership in women’s and lifestyle magazines.

Establishing a policy focus on obesity per se

In this setting, obesity experts in 1995 asked for a public campaign to change doctors ’ and governments ’ attitudes. Given the previous experience, however, it was clearly necessary first to establish the magnitude of the problem internationally and then work out how to focus government attention to induce action. This led to the formation of the International Obesity Taskforce (IOTF). Its aim was to galvanize the scientific community to produce a comprehensive dossier of evidence to convince WHO and indeed the nutrition community, preoccupied as usual with the challenges of undernutrition, that the global scale of the obesity epidemic affected even developing countries where there was a double burden of disease. Within a year of its formation, the IOTF had presented its dossier to WHO, and helped WHO convene an expert meeting in June 1997. With unprecedented speed, an interim report was prepared and printed by May 1998.

The report would typically have languished in boxes in basement corridors, but the IOTF drew the attention of ministers to it during the World Health Assembly. One minister, the Honourable Elizabeth Thompson, then Minister of Health for Barbados and chair of the Commonwealth Health Ministers meeting, decided to make obesity one of the themes of the Commonwealth’s triennial meeting over which she was to preside in Bridgetown later that year. This was significant, because the ability to address directly more than 50 health ministers should not be underestimated. Several health ministers acknowledged the problem, but they had no need to react because there was no pressure from their “constituency”. There was also no ready-made toolkit for ministerial action, so IOTF had to refocus on the recommendations of the earlier controversial WHO 797 report.8 It also had to engage the media and progressively analyse what to do in practice.

It was recognized that there were deficiencies in the original report as there was no appropriate method of assessing childhood obesity, and the economic impact of obesity was poorly assessed. The IOTF group, chaired by Bill Dietz, established the IOTF criteria for childhood obesity, and Tim Gill, Boyd Swinburn, Shiriki Kumanyika and colleagues set out a series of approaches and proposals, which form the current framework for preventive action.

The IOTF’s relocation to new headquarters in London increased its visibility and accessibility to the media, leading to the inclusion of obesity as front-cover stories in influential publications such as Time magazine, Newsweek and Forbes. This required thorough background briefings to journalists, who were genuinely interested in exploring in depth this new “headline” health story.

All this publicity merely accentuated the acknowledgement of the problem by politicians and, despite the systematic pressure of numerous reports—mostly based on highlighting the trends and putative problems of obesity—little was achieved. Then IOTF took part in the first WHO global analysis of the risk factors responsible for the burden of disease, which showed that excess weight gain was one of the top six risk factors for disability and premature deaths globally. This dramatic development stimulated numerous governments and health-associated groups to assess their policies, but yet again inaction prevailed. Several countries set out the principles for action, but placed the major emphasis on health educational approaches. The medical profession, without a coherent speciality for obesity comparable with, for instance, cardiology or rheumatology, remained cynical and reluctant to become too involved. The one improvement, however, was that by 2002 support among NGOs concerned with heart disease, diabetes and cancer was beginning to grow.

IOTF was then invited to take part in a WHO Western Pacific Regional meeting to discuss the prevention of chronic disease with more than 30 ministers of health. As usual, IOTF received a polite but detached hearing until the words “childhood obesity” were used as an additional issue. At that point every minister present suddenly focused and demanded to know how they should proceed to tackle this escalating problem in countries such as China, Japan and the Pacific Islands as well as Australasia. They also agreed with the “outrageous” proposition that they were actually very weak in terms of their capacity to put pressure on their government for action or special measures; health ministries constantly ask for more money to cope with their escalating medical costs but they generally lose out because the drivers of govern-It became clear that ministers were anxious to focus on children because this demonstrably demanded societal action rather than invoking personal responsibility. It was also clear, however, that no minister was prepared to confront the titanic power of the agricultural/food chain industries.

WHO recognized that new initiatives were needed, and with the broad support for its development of the Framework Convention on Tobacco, WHO then decided to address the need to improve diet—a challenge that would inevitably revive conflict with the global food industry. An expert consultation was, therefore, convened to reassess the WHO 797 report. WHO adopted a public consultative process prior to the finalizing of the new expert report, which became known as the WHO “916” report.10 This was a key part of the process of attempting to disarm an antagonistic food and beverage sector prior to the preparation of the WHO’s Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health.*

The political ramifications of these initiatives were obvious, but few academics were ready for the ferocity of the food and beverage industries’ assault on WHO, led by the sugar industry. An industrial counter-offensive, which rapidly escalated from a whispering campaign to an overt denunciation of the 916 report as “bad science” made the diet strategy a major global news story. To her credit, the Director-General of WHO, Dr Gro Harlem-Brundtland, chose to launch the report in person at the FAO’s headquarters in Rome, expressing her solidarity and support as she stood shoulder to shoulder with the report’s vice-chair, Professor Shiriki Kumanyika.

Even within the obesity field, food lobbyists attempted to drive a wedge between researchers using those dependent on industry funding, and in the US the sugar industry embarked on ad hominem attacks on selected experts, while distributing sweeteners in Washington DC. It even managed to mobilize senators to suggest that the US government might refuse to honor its funding obligations to WHO if it did not relent over the 916 report.

Simultaneously, the sugar industry was employing scare tactics in sugar-producing developing countries, spreading rumors that their local industries would suffer if the WHO recommendation to limit added sugars to less than 10% of dietary energy was adhered to. Focusing on the agriculture ministries meant the financial “fear factor” was taken seriously, and the pressure on WHO was intensified by an elaborate and secret critique delivered to the Director-General personally by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Timely media coverage exposed the clumsy maneuvering of the DHHS Secretary, Tommy Thompson, to a barrage of protests within the USA as health professionals and NGOs recognized the unseemly response of the Bush administration to industry pressure.

The WHO’s global strategy was eventually approved in Geneva in May 200411—but only after an extended debate in which the USA—represented by George Bush Snr’s godson, William Steiger—insisted that even a footnote referring to the WHO 916 report must be excised from the final text.

Achieving synergy among non-governmental organizations

To strengthen WHO in the implementation of its Global Strategy, the IOTF, with its own parent body, the International Association for the Study of Obesity, brought together a number of NGOs to form the Global Prevention Alliance. This consolidated the early collaboration that had developed with the International Diabetes Federation, the World Heart Federation, the International Union of Nutritional Sciences and the International Pediatric Association.

This Global Alliance paved the way for a series of initiatives to begin to galvanize national NGOs in a number of countries to engage with their governments and ministries in response to the global strategy. This catalytic action prompted groups to be formed initially in a range of countries, for example, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Hong Kong and Brazil. A broader analysis also revealed that most medical leaders have little understanding of public health policy-making and often spend their time vying for preferential ministerial attention to their own speciality. Nevertheless, WHO Europe, with major NGO support, managed to convince European ministers of health to sign a charter on obesity, which included calls for many changes using legislative and regulatory measures. This is, of course, simply a charter and has no binding political significance, and similar solidly founded documents produced in countries such as the UK or Australia, which outline the dimensions and forces involved in promoting obesity, do not in themselves lead to coherent remedial action. The simple explanation is that ministers consider it unwise to take on the greatest industrial powers in the land. The “big food” corporate sector includes multinational companies that have a greater turnover than many countries.

The recent analysis of obesity, undertaken as part of the British Government’s Foresight Programme,12 has illustrated in great detail the intricate “hard-wiring” of the vast array of governmental and civil society components that must be considered when attempting to deal with the multi-factorial pressures leading to obesity. This recognition of the need for an overarching “societal” approach, combined with the analysis of the projected economic burden12 to society from obesity, was instrumental in the development of the UK Government’s cross-sectoral strategy on obesity.13 Even so, this still does not really tackle the key industrial factors which guarantee an escalating rate of obesity. The climate of opinion is beginning to move towards much higher expectations for action, and this has led initially to vague pledges by industry to improve the nutritional quality of product ranges.

They have also made limited gestures towards placing some constraints on marketing to children in an effort to evade the prospect of more stringent measures being enforced. This has been enough to draw some medical and nutritional experts into collaboration with industry, where they have the impression that they are playing an important role in the political process, so should not challenge the politicians to greater action. This requires clearly independent, media-sensitive groups to lobby for ever greater change, so that reputable advisers can legitimately press for progressive and innovative strategies to be implemented.

Given the failure of any government to date to address the major structural changes needed to counteract obesity, one can reasonably ask: How it is possible to generate the political will to induce substantial changes in government policy? Clearly a combination of measures is needed.

First, a focus on highly visible problems with an emotional trigger is useful, such as the rise in childhood obesity, because this demands urgent government action. Second, the focus on the marketing issue is also politically valuable because it invokes major parental and public concern. Third, economic analyses are crucial, as was demonstrated in the UK response to predictions of the economic implications of obesity. The obesity community must now develop these economic analyses as effective tools for global use. Fourth, ministries of health cannot be the sole focus for influencing the agenda, as IOTF has repeatedly found.

Thus, through the Global Alliance initiative, the IOTF, using personal contacts at the highest level, has managed to help introduce obesity and the prevention of chronic diseases into the next five-year Economic and Social Development Plan for Thailand, with the strong backing of the Director General of the Economic and Social Development Board of Thailand.

Similarly IOTF was recently invited to address the 16 Caribbean presidents and prime ministers on the economic and health burden on the Caribbean populations. This was only achieved through long-standing personal contacts with a key individual, Sir George Alleyne, ex-Director of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), who was trusted by the leaders because they already had experience of his wisdom. Plans are now being devised locally on the basis of preliminary proposals but these, again, will need very careful monitoring if they are to be effective rather than simply politically promoting an image of action.

Fundamental to creating a climate for action is the need to ensure the capacity to deliver a sustained message, perhaps over many years. While many civil society groups hope for swift results, history suggests that health issues that do not convey an immediate and potentially fatal threat and which, like food quality, are seemingly under individual control, do not have staying power in terms of political priorities. As with smoking, there is a need for a medical consensus and an emotive focus combined with economic arguments, together with explicit proposals that will allow heads of government or finance ministers to change their policies on the basis of some definite political gain. Health professionals cannot afford to relax in their efforts to bring home to the public, politicians and producers the need for fundamental and long-term improvements in the nutritional quality of the whole range of products in the food supply chain if the obesity epidemic and consequent chronic diseases are to be brought under control.

1 James WPT, Ralph A, Bellizzi M: Nutrition policies in Western Europe: National policies in Belgium, France, Ireland, the Netherlands and the United kingdom. Nutr Rev 1997; 55: S4–S20.

2 Bray GA: Fogarty Center Conference on Obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1974; 27: 423–424.

3 Waterlow JC (chairman): Research on Obesity: Report of A DHSS/MRC Group. London: HMSO, 1976.

4 Royal College of Physicians. Obesity. Report by the Royal College of Physicians J R Coll Physicians Lond 1983; 17 (1): 1–58.

5 Smoking and Health. Summary of a Report of the Royal College of Physicians of London on Smoking in relation to Cancer of the Lung and Other Diseases. Royal College of Physicians London, 1962.

6 Prevention of coronary heart disease. Report of a joint working party of the Royal College of Physicians of London and the British Cardiac Society. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1976; 10 (3): 213–275.

7 National Advisory Committee on Nutrition Education: A Discussion Paper on Proposals for Nutritional Guidelines for Health Education in Britain. London: Health Education Council, 1983. see: Robbins C: Implementing the NACNE report. 1. National dietary goals: a confused debate. Lancet 1983; 2 (8363): 1351–1353. Sanderson ME, Winkler JT: Nutrition: the changing scene. Implementing the NACNE report. 2. Strategies for implementing NACNE recommendations. Lancet 1983; 2: 1353–1354. Walker CL: Nutrition: the changing scene. Implementing the NACNE report. 3. The new British diet. Lancet 1983; 2: 1354–1356. Jollans JL: Implementing the NACNE report: an agricultural viewpoint. Lancet 1984; 1: 382–384.

8 World Health Organization: Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Report of a WHO Study Group. WHO Technical Report Series 797. Geneva: WHO, 1990.

9 FAO, WHO: Nutrition and development—a global assessment, written by FAO and WHO for the International Conference on Nutrition, 1992.

10 World Health Organization/Food and Agriculture Organization: Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. WHO Technical Report Series 916. Geneva: WHO, 2003.

11 World Health: Organization (WHO): Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. WHO, 2004.

12 Foresight: Tackling Obesities: Future Choices—Modelling Future Trends in Obesity & Their Impact on Health. Government Office for Science (UK), 2007.

13 Foresight: Tackling Obesities: Future Choices—Project Report, 2nd edn. Government Office for Science, 2007.

*Three of the editors of this book played prominent roles in the 916 group. Professor Ricardo Uauy was chair, Professor Jaap Seidell was a rapporteur, and Professor Boyd Swinburn was also a prominent member. Another IOTF working group chair, Professor Shiriki Kumanyika, was deputy chair of the expert meeting, and Professor Philip James, chair of the IOTF and chair of the original 797 report, was also a member.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree