Summary

In this chapter we discuss the:

- definition of poverty and financial stress;

- definition of household food insecurity;

- prevalence of food insecurity in children in countries with developed and developing economies;

- impact of household food insecurity on well-being in children (health, mental, social well-being);

- relationship between socio-economic disadvantage, poverty and food insecurity and the prevalence of obesity in children;

- possible explanations for the overlap between poverty, household food insecurity and obesity in children;

- social, economic and public health policies to address childhood poverty and household food insecurity—can they have an impact on obesity in children?

What is poverty?

Absolute poverty, as generally experienced in countries with developing economies, is a condition characterized by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information. For example, the WHO estimates that more than 45% of the population of the African region fall under the poverty-line definition, which characterizes as “poor” anyone who cannot afford a daily consumption rate of US$1.1

The poverty experienced in the developed world is considered relative. In these countries, people are considered poor if their living standards fall below an overall accepted community standard, and they are unable to participate fully in ordinary activities of society. This relative poverty can also be measured in terms of household income and a poverty line which is a defined income that families of different sizes need to cover essential needs. OECD countries use 50% of average disposable income to define a poverty line.2

What is financial stress?

Household income reflects economic resources. Measurement of financial stress concentrates on what people spend their money. It considers the extent to which households may have been constrained in their spending activities because of a shortage of money.3 In developed countries financial stress may mean being unable to pay bills on time or needing to borrow money from friends or family or, at the extreme, being unable to afford heating and meals, or having had to pawn or sell possessions, or needing assistance from community organizations.

Financial stress impacts on household food expenditure. In households experiencing financial stress, food can become an elastic, and sometimes discretionary, expense resulting in changes in the quality and/or quantity of food purchased and available for consumption by adults and children in the household.

What is household food security?

Food insecurity is the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or the limited ability to acquire foods in socially acceptable ways.

Food insecurity … refers to the social and economic problem of lack of food due to resource or other constraints, not voluntary fasting or dieting, or because of illness, or for other reasons. This definition, supported by … ethnographic research … means that food insecurity is experienced when there is (1) uncertainty about future food availability and access, (2) insufficiency in the amount and kind of food required for a healthy lifestyle, or (3) the need to use socially unacceptable ways to acquire food. Although lack of economic resources is the most common constraint, food insecurity can also be experienced when food is available and accessible but cannot be used because of physical or other constraints, such as limited physical functioning by elderly people or those with disabilities. Some closely linked consequences of uncertainty, insufficiency, and social unacceptability are assumed to be part of the experience of food insecurity. Worry and anxiety typically result from uncertainty. Feelings of alienation and deprivation, distress, and adverse changes in family and social interactions also occur … Hunger and malnutrition are also potential, although not necessary, consequences of food insecurity.4

Measuring household food insecurity

The term food insecurity can be used in relation to individuals, households and communities.5 Essentially, in high-income countries, household food insecurity is an economic and social condition of limited access to food. The food security status of households can be measured using validated tools. A variety of approaches have been used to measure household food insecurity.6 The best known tool is the USDA 6 or 18 item US Household Food Security Survey Module. This measures food security on a continuum from:

- High food security—households have no problems, or anxiety about adequate food.

- Low food security—households reduce the quality, variety and desirability of their diets, but the quantity of food intake and normal eating patterns are not substantially disrupted.

- Very low food security—at times during the year, eating patterns of one or more household members are disrupted and food intake reduced because the household lacked money and other resources for food.

In low- and middle-income countries, interest in using similar tools has led to consensus on a generic questionnaire that, when adapted to the socio-cultural setting, will provide useful measurements of household food insecurity in many countries.7 This consensus emerged from two international workshops organized by the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project (FANTA), and is based on work carried out in Indonesia,8 Bangladesh,9 Brazil10 and other countries.11

Other markers for food insecurity when no measurement tools exist

Before the development of survey questionnaire tools to measure household food insecurity, other proxy measures had been used, and are still used. Some of these methods are based on agricultural productivity, food storage, or children’s nutritional status.12 Others are based on coping strategies, food economy, community ranking and livelihood assessment.6

Prevalence of food insecurity in children

The most recent Australian data from the Victorian Population Health Survey found that in 2006 3.6% of two-parent families with dependent children and 20.6% of one-parent families with dependent children had in the last year run out of food and had no money to buy more13 In the United States, from national survey data in 2006, 89% of households were food secure throughout the entire year, with the remaining 11% of households being food insecure at least some time during that year14 Among households with dependent children, 16% were food insecure. The US prevalence of very low food security was 4% of households, with these households having disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake during the year because the household lacked money and other resources for food. Some assessment has been done in low-income countries. For example, a survey in Java, Indonesia, at the height of the economic crisis that struck in 1998, saw substantial household food insecurity with 94.2% of households found to be uncertain or insecure about their food situation in the previous year, and 11% of respondents reported losing weight in the previous year because of lack of food.8

Impact of food insecurity on a child’s well-being

A number of factors determine the food security status of a household including financial resources, local food access and cost, social support and networks, skills, values and attitudes and the mental and physical health of the primary care giver. The experience of food insecurity for a child has both the immediate impact of little or no food in the home but also the long-term consequences for both child and parent of an uncertain supply of food. Household food insecurity has been shown to relate to poor physical and mental health, social development, and academic performance, including higher prevalence of inadequate intake of key nutrients, depressive symptoms and suicide risk in adolescents, and poor learning and behavior problems in children.4

The relationship between poverty and food insecurity and the prevalence of obesity in children

Relationship poverty and obesity in children

How can children in families that are poor or otherwise disadvantaged be obese? Historically the image of poverty and disadvantage was one of a wasted child and/or parent. But this image has effectively been turned on its head. In countries with developed and, even developing economies, many people who are socio-economically disadvantaged, living on low income or in poverty, and are food insecure, are overweight or obese.

The results of early studies looking at the relationship between socio-economic status (SES) and childhood obesity were inconsistent. Sobal and Stunkard’s review in 1989 of 34 such studies from developed countries published after 1941, found inverse associations (36%), no associations (38%), and positive associations (26%) were in similar proportions.15 More recent data, however, indicate that the inverse gradient between SES and adiposity in adults16 is becoming apparent in children. A systematic review of cross-sectional studies for the period 1990–200517 indicates that, within the past 15 years, the associations between SES and adiposity in children are predominantly inverse, and positive associations have all but disappeared. These findings are corroborated by recent analyses of nationally representative samples of children. For example in the UK, Stamatakis et al 2005, using data from the National Study of Health and Growth and the Health Survey for England, found that while obesity was increasing in all children, it was increasing more rapidly among children from low income homes.18 In Australia, Wake et al 2006 in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) found again that obesity in children was increasing across the board but that children from highly disadvantaged neighborhoods were 47% more likely to be overweight or obese compared with those from areas with more advantages.19

The relationship between poverty and childhood obesity is well described in a comparative study of Canada, Norway and the USA.20 These countries were chosen because, while they are similarly affluent, they have made quite different social policy choices and have correspondingly different socio-economic outcomes for children. Canada and the USA can both be considered welfare states with relatively low levels of public spending, income transfers which are targeted to the poor rather than universally available and high rates of child poverty. In contrast, Norway has higher levels of public spending, more universal and generous spending and much lower rates of child poverty. In this study, the patterns of poverty and child obesity were lowest in Norway. In both Canada and the USA, there was a greater extent of obesity for poor than non-poor children, and this pattern was particularly marked for the USA. This study suggests that an association does exist between poverty and childhood obesity and that this may be moderated by social policies.

Studies of measures of poverty or financial stress and obesity in the USA

A number of US studies have demonstrated a modest but consistent association between food insecurity and weight status in adult women. This association and the case report published by Dietz in 1995 has stimulated a number of investigations of the association between household food insecurity and weight status in children.21 While many of the studies cannot provide evidence of causal relationship, owing to limitations in study design and measurement, these studies generally find only limited evidence of any relationship between food insecurity and child over-weight. In secondary data analysis of nationally representative US datasets, Casey22 found no relationship between food insecurity and weight status independent of income, Alaimo23 found that white girls aged 8–16 were slightly more likely to be overweight if they lived in a food insufficient household, and Rose24 found that kindergarten children were less likely to be overweight if they were living in a food insecure household.

The few smaller studies published have also reported inconsistent and weak evidence of associations between food insecurity and child weight status. Matheson and colleagues25 reported a lower BMI among children in food insecure households in a cross-sectional sample of 124 Hispanic families, but Kaiser26 reported no association in another sample of younger Hispanic children. At the time of writing, there is only one published study that examines the longitudinal associations between food insecurity and overweight. Jyoti27 found that girls from food insecure households had greater gains in BMI than girls from food secure households, but average BMI remained within the normal range. There are a number of plausible explanations for the lack of a clear association between food insecurity and obesity in children. It is possible that children, particularly young boys, are protected from food insecurity through their parents’ coping strategies. It is also possible that programs available to protect children from the effects of household food insecurity are working, in that children are receiving adequate and healthy meals from school and child care environments.

Studies in other developed economies

Other than the USA, there are few countries with developed economies in which the relationship between food insecurity and childhood obesity has been measured. One country in which this research has been undertaken is Canada.

Canada’s National Population Health Survey 1998–1999 found that 11% of children <18 years lived in households where food insecurity compromised diet. In this survey, children were five times more likely than seniors to be living in a food insecure household.28 Using data from the Longitudinal Study of Child Development, Dubois29 found that the presence of family food insufficiency during preschool years increased the likelihood of overweight three-fold after adjusting for income. This study reported that low birthweight children living in households that experienced food insufficiency during preschool years were at higher risk of becoming overweight at 4–5 years.

Implications for research and practice

There is evidence that an association exists between socio-economic disadvantage, poverty and obesity in children. It would appear that social policy can influence the socio-economic conditions in which children live and lessen the likelihood of a child becoming obese. Evidence for an association between food insecurity and obesity is less consistent and may be country dependent. While a very strong association has been demonstrated in Canada, the US results indicate a weaker link. Again, these differences may reflect different social policies in each of these countries that moderate either the likelihood of a household being food insecure or the impact of food insecurity on a child’s health and relative body weight.

Where do we go from here? We need to improve our understanding of both how to reduce childhood poverty and disadvantage and also how to develop policies that can target solutions in the pathways between poverty and obesity in children. Research should be directed at understanding these pathways using cross-national and longitudinal comparisons. To best articulate policy regarding either childhood obesity or food insecurity, countries with developed economies need research that goes beyond examining associations of food insecurity and obesity in children. For instance, in the USA, a number of policies have been developed and programs implemented to address food insecurity in children (e.g., the School Meals Programs, The Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children and The Food Stamp Program). For almost as long as the programs have been in existence, there have been concerns that they may contribute to obesity.30 Even though most studies have demonstrated that program participation leads to better diet quality, some have also shown that children may consume more sweetened beverages and consume more fat when participating in the program. Future research regarding food insecurity and obesity in children needs to use new and innovative methods to examine the best policy options for protecting children from the negative effects of household food insecurity without exacerbating risk factors for obesity.

Why would children from poor or food insecure households be more likely to be obese?

As described elsewhere in this book, obesity is the product of an imbalance between energy intake (food intake) and energy output (physical activity). The literature consistently shows that children living in households with fewer socio-economic resources are less likely to have a healthy diet or engage in physical activity and are more likely to be unhealthy and obese.31 It is not fully understood why this socio-economic gradient in health and lifestyle behaviors exists in adults and children.32 It is likely that an explanation lies both within the environment, that is, our cities, neighborhoods and society in general and within the child’s immediate environment, that is, their home. A good representation of the macro factors which operate at a societal and environmental level is the ecological model of health and development across the lifespan.33 However, described in the ecological model, there are the micro factors operating at household and individual parent and child level that are also determinants of a child’s health and development. The link between these factors operating within the caregiving environment (the home) and child health and development are described by the UNICEF conceptual framework.34 The pathway between poverty, financial stress and food insecurity and childhood obesity is likely to be explained by both environmental factors and differences in caregiving and resources for caring within the home.

Macro environmental factors that may impact on the prevalence of obesity in food insecure or poor households

The effect of the economic and social environment on the development of obesity may be moderated by policies or structures that determine household economic resources. We know that those with fewer economic resources are more like to be obese.16 Ecological studies indicate that larger increases in energy intake, obesity and diabetes, particularly among women, can be observed in developed countries where greater income disparities are also observed.35 As described previously, studies also indicate that levels of inequity and wealth distribution influence the prevalence of childhood obesity.20

There is evidence that the food environment, the availability and cost of food, may increase the likelihood of those on low income or living in poverty becoming obese. Studies of the food environment indicate that the idea of poor neighborhoods having too little and too expensive healthy foods holds true only in the USA.36 Studies in the UK37 and in Australia38 indicate that low income areas have good access to affordable healthy food. However, what has been consistently shown in the developed world is a strong relationship between area level disadvantage and the density of fast-food outlets. The cost of food may also accelerate obesity among the socio-economically disadvantaged.39 Evidence is emerging that the global price of food is increasing. Data from Australia reveal that the cost of healthy staples has increased 20% above inflation while, in comparison, the price of unhealthy foods, such as soft drinks and cakes and biscuits, has steadily dropped.40

Studies also indicate socio-economic disparities in the built environment in terms of access to resources including playgrounds, equipment and neighborhood safety that would encourage physical activity. It is believed that these in part explain socio-economic differences observed in participation in physical activity and engagement in sedentary behaviors.

Household factors determining obesity in poor or low income households at risk of food insecurity

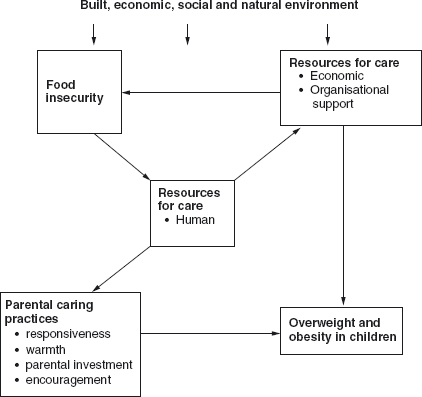

In addition to environmental factors, we propose that the development of obesity among children in poor and food insecure households is a product of the impact of this deprivation on parental care giving. It is well recognized that care giving practices and resources for caring have a powerful influence on children’s development.41 The significance of care has been best articulated in the extended UNICEF (1996) model of care.34 This model has been used extensively in countries with developing economies to explore the link between food insecurity and malnutrition. We propose that the model can be adapted to explain the relationship between food insecurity and obesity, which is largely an issue in developed countries or those in economic transition. It is ironic that a model essentially used to explain malnutrition in developing countries could be applied to explain obesity in developed countries. However, obesity and malnutrition can coexist in households in developed countries and countries with developing economies and food insecurity is prevalent in these countries though not as visible as in developing countries.

Using the UNICEF model, Begin demonstrated42 that care givers’ influence on child feeding decisions, their satisfaction with life, and the help available to them, were more closely related to child development than household variables including income and the care givers’ time allocation for different activities of living. We have built on this model and propose (see Figure 16.1) that, while financial resources (or lack thereof) maybe important in the development of obesity, financial hardship and food insecurity has an additional effect, which is mediated by stress on carers’ resources and parental caring behaviors.

Figure 16.1 Model of the relationship linking food insecurity, resources for care and parental caring practices to overweight and obesity in children within the context of the built, economic, social and natural environments.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree