Women’s Sexuality and Sexual Dysfunction

Rosemary Basson

Sexual rights … include the right of all individuals … to (achieve) the highest attainable standard of health in relation to sexuality and to pursue a satisfying, safe and pleasurable sexual life.

—World Health Organization Working Definition, 2002

That sexual function is a legitimate aspect of medicine is clearly shown in the above declaration of sexual rights. National probability samples and clinical studies from many countries confirm that most men and women consider their sexual well-being as important. Nevertheless, studies suggest that fewer than one third of women who experience ongoing sexual problems have had these problems addressed by their physician. Moreover, the majority of women consider it appropriate for their physicians to take the initiative to inquire about sexual health, and a recent study of older minority women attending a primary care practice confirmed that significantly more would identify their sexual problems if the physician used an introduction such as “Many women after menopause have sexual problems, how about you?” Recent data show that regardless of any surgery-associated sexual changes, satisfaction with a hysterectomy increases if there is preoperative assessment of sexual function along with information about possible positive and negative effects on sexuality from a hysterectomy. In order to assess and manage common sexual dysfunctions, it is necessary for gynecologists and primary care physicians to understand women’s variable sexual responses and some of the differences between men and women’s sexuality.

Women’s Sexual Response Cycle

There are different phases of sexual response, including desire, arousal, and orgasm followed by relaxation and well-being. However, particularly in women, these phases are not discreet, nor is their order invariable. Especially when in established relationships, women mostly initiate sex or accept their partner’s invitation without any marked sense of sexual desire at that time. Qualitative research has clarified many of the reasons a woman instigates or accepts sexual engagement such as the enhancement of emotional closeness with her partner, finding herself responding to a romantic environment and, more specifically, to erotic cues. Other reasons include wanting to feel better about herself, more normal, more loved, more committed to the relationship, to conceive, and sometimes for more nefarious reasons. Sexual desire, as typified by sexual fantasizing, positively anticipating sexual experiences, and spontaneously needing partnered sex or self-stimulation, has a broad spectrum of frequency across women. It is also clear that such overt desire is infrequent in many sexually functional and satisfied women.

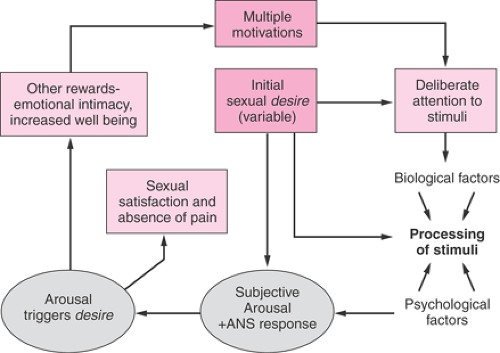

The sexual response cycle, then, may or may not feature desire initially; rather, the woman may be motivated by other reasons, including wanting to be emotionally close to her partner such that she deliberately attends to sexual stimuli, and as a result of subsequent subjective arousal (excitement) and pleasure, feelings of sexual desire are triggered. Desire and arousal then coexist and compound each other, as shown in Figure 43.1. Provided that the duration of stimulation is sufficiently long and that she continues to attend to the stimuli and continues to feel pleasure, sexual satisfaction follows with one, many, or no discreet orgasms, thereby fulfilling her newly acquired sexual desire. Her original motivations and goals that encouraged her to be sexual initially will also be achieved. So, the response is circular with overlapping phases of variable order. Desire may follow arousal, and high arousal may follow the first orgasm. Desire, once triggered, can increase the motivation to attend to sexual stimuli and to accept or request

more intensely erotic forms of stimulation. Any initial or spontaneous desire also will augment the response at many sites in the circle. This circular response cycle also reflects male sexuality: however, data indicate that men begin with a sense of desire far more frequently than do women.

more intensely erotic forms of stimulation. Any initial or spontaneous desire also will augment the response at many sites in the circle. This circular response cycle also reflects male sexuality: however, data indicate that men begin with a sense of desire far more frequently than do women.

Contained in the model shown in Figure 43.1 is the concept of arousability, meaning the ease with which the woman is aroused by sexual stimuli. This concept is important given the evidence that many factors modulate arousal, including feeling desired rather than feeling used, feeling accepted by the partner, finding the partner’s behavior attractive, having a positive body image and positive mood, and having positive sexual experiences in the past as well as biologic factors such as testosterone, thyroid, and prolactin.

Complexities of Women’s Sexual Arousal

The evidence-based conceptualization of women’s sexual response shown in Figure 43.1 emphasizes subjective arousal rather than genital congestion per se. In the past, women’s arousal was equated to vaginal lubrication and vulval swelling (as in the definitions of sexual disorders in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders). More accurately, lubrication is an epiphenomenon. Some lubrication is necessary when intravaginal stimulation is part of a couple’s interaction, but neither lubrication nor genital swelling nor the degree of underlying congestion correlate well with subjective arousal on empirical testing. This has been demonstrated repeatedly during the past 30 years by using a tamponlike device (vaginal photoplethysmograph [VPP]) that measures increases in genital congestion while a woman watches an erotic video and rates her subjective excitement simultaneously with the measures of congestion. Women with chronic complaints of low arousal typically show VPP measures identical to control women while watching erotic videos but report no subjective excitement. Similarly, according to preliminary studies, there is little correlation between increases in clitoral volume, as measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or ultrasound-measured increases in clitoral blood flow and women’s subjective arousal as they view erotica. Unlike penile erection in men, genital congestion in women does not robustly reinforce their subjective excitement.

Women’s genital congestion appears to be automatic and nonselective. Women (but not men), when watching visual stimuli that were considered by healthy volunteers to be sexual but not erotic or arousing (videos of primates mating), had evidence of genital congestion in response to the stimulus. Both lesbian and heterosexual women show substantial genital response to both preferred and nonpreferred genders depicted in erotic videos. However, men show patterns of responding that correspond to their preferred gender.

Physiology of Women’s Sexual Response

Physiology of Desire and Subjective Arousal

Feelings of sexual desire can be triggered by internal cues such as memories of sexual experiences or by external ones such as a romantic environment and are dependent on certain, and as yet not fully understood, biologic mechanisms. Multiple neurotransmitters, peptides, and hormones modulate desire and subjective arousal: noradrenalin, dopamine, melanocortin, oxytocin, and serotonin acting on some serotonin receptors are prosexual, whereas prolactin, serotonin acting on 5-hydroxytryptamine 2 and 3 (5HT2, 5HT3) receptors, glutamate, vasopressin, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)

are inhibitory. There is complex interplay between the neurotransmitters and peptides and the sex hormones. There also is complex interplay between environmental and neuroendocrine factors. For instance, even in animal models, either dopamine or progesterone can act on receptors in the hypothalamus to cause an increase in sexual behavior in the oophorectomized estrogenized female rat. Of note, however, is that the presence of a male animal in an adjacent cage can cause an identical change in sexual behavior without the administration of either progesterone or dopamine. One corollary in women is that intensity of sexual response can be increased by raising serum testosterone levels in midlife women to those of younger women, by administering a dopaminergic drug such as bupropion, or by beginning a new relationship with a new partner. Animal experiments also demonstrate how the female assesses the context of potential sexual activity, relates it to past experience and therefore to expectation of reward, and adjusts her sexual behavior accordingly. In women, it is known that factors such as attitudes to sex, feelings for the partner, past sexual experiences, duration of relationship, and especially mental and emotional health more strongly modulate desire and arousability than do the biologic factors that have been investigated so far. It should be noted, however, that the data supporting the issues mentioned stem from nationally representative samples of women, not specifically from women with chronic disease, who may make up a large percentage of a gynecologist’s practice. The disease itself and its treatment as well as its psychologic effects can all add to the interpersonal, personal, and contextual issues mentioned that impact on sexual response.

are inhibitory. There is complex interplay between the neurotransmitters and peptides and the sex hormones. There also is complex interplay between environmental and neuroendocrine factors. For instance, even in animal models, either dopamine or progesterone can act on receptors in the hypothalamus to cause an increase in sexual behavior in the oophorectomized estrogenized female rat. Of note, however, is that the presence of a male animal in an adjacent cage can cause an identical change in sexual behavior without the administration of either progesterone or dopamine. One corollary in women is that intensity of sexual response can be increased by raising serum testosterone levels in midlife women to those of younger women, by administering a dopaminergic drug such as bupropion, or by beginning a new relationship with a new partner. Animal experiments also demonstrate how the female assesses the context of potential sexual activity, relates it to past experience and therefore to expectation of reward, and adjusts her sexual behavior accordingly. In women, it is known that factors such as attitudes to sex, feelings for the partner, past sexual experiences, duration of relationship, and especially mental and emotional health more strongly modulate desire and arousability than do the biologic factors that have been investigated so far. It should be noted, however, that the data supporting the issues mentioned stem from nationally representative samples of women, not specifically from women with chronic disease, who may make up a large percentage of a gynecologist’s practice. The disease itself and its treatment as well as its psychologic effects can all add to the interpersonal, personal, and contextual issues mentioned that impact on sexual response.

Physiology of Physical Sexual Arousal

Physical changes of sexual arousal include increases in blood pressure, heart rate, muscle tone, respiratory rate, and temperature in addition to genital swelling, increased vaginal lubrication, breast engorgement, nipple erection, increased skin sensitivity to sexual stimulation, and a characteristic mottling of the skin or “sexual flush” consisting of vasodilation over the face and chest. The response of the autonomic nervous system increasing blood flow to the vagina occurs within seconds of a visual sexual stimulus. There is increase in blood flow through the arterioles supplying the submucosal vaginal plexus, which increases the transudation of interstitial fluid from the capillaries across the epithelium and into the vaginal lumen. This rapid transit alters the electrolyte composition such that there is less potassium and more sodium than in the lubrication fluid in the unaroused state. There also is relaxation of smooth muscle cells around the blood spaces or sinusoids in the clitoral tissue. The latter includes the rami, shaft, and head of the clitoris as well as the extensions of clitoral tissue known as vestibular bulbs. As the clitoris becomes more swollen, the shaft elevates to lie near the symphysis pubis. The inner two thirds of the vagina lengthen and extend, elevating the uterus. It has been hypothesized that during intercourse, penile thrusting on the cervix might cause reflex contraction of the pelvic muscles, thereby facilitating the “ballooning” of the upper vagina, while the same muscle contraction constricts the lower vagina. This is described as a “cervical motor reflex,” whereby touch to the cervix reduces pressure in the upper portion of the vagina and increases pressure in the middle and lower portions with documented increased electromyographic activity in the levator ani. It is possible that the elevation of the uterus for sexual arousal is in part due to a further recently described reflex. Reduced uterine tone has been demonstrated in response to mechanical or electrical stimulation of the clitoris. It was apparent that clitoral stimulation abolished the background tonic uterine muscle contraction, such that uterine pressure declined. External changes include swelling and darkening of the labia minora. The increased congestion of the introitus actually narrows its diameter.

Neurotransmission of genital congestion is incompletely understood. Far more studies have been done to clarify male genital sexual physiology than female. The major neurotransmitter involved in clitoral engorgement is nitric oxide (NO), which is released from parasympathetic nerves along with vasointestinal polypeptide (VIP). Simultaneously, acetylcholine (Ach), which blocks noradrenergic vasoconstriction and promotes NO release from the endothelium, is released. Somatic, sympathetic, and parasympathetic nerve pathways are far less separate from each other than was formerly believed. There is documented communication between the NO containing cavernous nerve to the clitoris and the distal portion of the somatic dorsal nerve of the clitoris from the pudendal nerve. Recent work shows that input from the ganglia of the caudal sympathetic chain containing noradrenalin and perhaps neuropeptide Y produces, as one would expect, vasoconstriction by the way of α-adrenergic and peptidergic receptors. On the other hand, input from the hypogastric nerve (sympathetic) passing through ganglionic relay stations in the pelvic plexus can produce vasodilation and vulval congestion as well as the opposite. Of note is that an increase in sympathetic tone brought on by exercise, hyperventilation, or experimental ephedrine administration increases the physiologic arousal response of genital congestion. Similarly, in sexually functional women, the prior viewing of visual triggers that provoke anxiety increases the physiologic genital arousal response to subsequent erotic visual cues.

Neurology of Clitoral Sensitivity

The clitoris is the most sexually sensitive structure, but there is little research into the transmission of sexual sensation. Recent immunohistologic studies have confirmed neurotransmitters thought to be associated with sexual sensations (substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide [CGRP]), concentrated directly under the epithelium of the glans. It is important to note that clitoral stimulation is usually enjoyable only if nonphysical and nongenital physical stimulation have previously occurred. Without

existing arousal, direct stimulation can be unpleasant, too intense, and even painful.

existing arousal, direct stimulation can be unpleasant, too intense, and even painful.

Physiology of Orgasm

The physiology of orgasm remains unclear. Definitions are not established but include “a psychic phenomenon, a sensation (cerebral, neuronal discharge) elicited by the accumulative effect on certain brain structures of appropriate stimuli originating in the peripheral erogenous zones” or “the acme of sexual pleasure of rhythmic contraction of perineal/reproductive organs, cardiovascular, and respiratory changes, release of sexual tension.” Given that men and women with complete spinal cord injury can experience orgasm, it currently is considered that orgasm primarily is a cerebral event. Recent positron emission tomography (PET) has shown women’s orgasm to be mainly associated with profound decreases of cerebral blood flow in the neurocortex compared with control conditions (clitoral stimulation and imitation of orgasm), particularly in the left lateral orbitofrontal cortex, inferior temporal gyrus, and anterior temporal lobe. Measuring extracerebral markers of orgasm, such as rectal pressure variability, showed significant positive correlations between the rectal pressure variability and cerebral blood flow in the left deep cerebellar nuclei. Thus, it currently is proposed that decreased blood flow in the left lateral orbitofrontal cortex signifies removal of behavioral inhibition during orgasm and that deactivation of the temporal lobe is directly related to high sexual arousal. The deep cerebellar nuclei may be involved in motor activity—the orgasm-specific muscle contractions, but as well the cerebellum is now known to be involved in emotions and integrating sensory information. It also is possible that involvement of the ventral midbrain and right caudate nucleus is indicative of a role for dopamine in female sexual arousal and orgasm. The cerebral changes lead to reduction of inhibitory serotonergic tone from the nucleus paragigantocellularis to the so-called orgasm center in the lumbosacral cord.

The sexual stimulus eliciting orgasm may be to the genitalia but also may be to the breasts and nipples or from sexual fantasy or sexual dreams. Women with complete spinal cord injury above spinal cord level T10 can have orgasms from vibrostimulation of the cervix, possibly mediated by branches of the vagus nerve. Damage to the pelvic autonomic plexuses from radical hysterectomy, for instance, does not preclude orgasm. The necessary autonomic nerves probably travel with somatic fibers S2, S3, and S4. Branches from the sympathetic ganglia to the union of S2, S3, and S4 parasympathetic and somatic fibers proximal to the superior hypogastric plexus have been identified. Despite clinical impressions to the contrary, weakening of the pelvic floor from vaginal deliveries has not been scientifically proven to correlate with sexual dysfunction. In keeping with the known physiology of orgasm, the most common drugs that impede orgasm are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Uterine contractions accompany orgasm, and a subset of women report altered orgasms after hysterectomy. The contractions of the pelvic floor muscles around the vagina during orgasm are variably perceived by women, and studies show the rhythmic contractions extend over many more seconds than the period of time during which women can feel their occurrence.

Physiology of Later Stages in Sexual Response: Relaxation and Well-being

There is little study of the neuropharmacology of the later stages in sexual response. The body gradually returns to its baseline state, and genital vasocongestion reverses. Any functional role of oxytocin or prolactin has yet to be established in humans. Increases in oxytocin with arousal have been inconsistently reported, and the more consistently reported increases in prolactin after orgasm have not been shown to have functional implications.

Role of the Cervix

The role of the cervix in sexual function has been widely debated. It has a rich vascular and nerve supply such that its loss might negatively affect sexual pleasure and the physiology of genital arousal. The recent studies comparing vaginal and subtotal or total abdominal hysterectomies do not support a role for preservation of the cervix to enhance women’s sexual function. Three studies were published in 2003. First, a prospective observational study of 145 women receiving abdominal hysterectomy, 89 receiving vaginal hysterectomy, and 76 receiving subtotal hysterectomy showed that there were no differences in sexual outcome among the three surgical methods. Second, a prospective randomized trial of 158 women having total abdominal hysterectomy and 161 having subtotal abdominal hysterectomy also showed no differences in sexual outcomes. The third was a retrospective study of 125 women undergoing classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy and 128 receiving total hysterectomy: no sexual benefits of CISH over total hysterectomy were reported. A subsequent randomized study of supracervical and total abdominal hysterectomy involving 135 women indicated similar sexual function during 2 years of follow-up. Another recent study included two control groups of women who did not undergo hysterectomy: one received minor gynecologic surgery, and the other was a healthy nonsurgical control group. Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy (total hysterectomy) was compared with laparoscopic subtotal hysterectomy. Both groups reported some improvement in sexual function, and both the surgical and normal control groups reported similar sexual complaints with similar frequencies as the hysterectomy groups. Similarly, hysterectomy would appear to be most often associated with improved sexual function. Detailed analysis of the small

percentage of women who report deteriorated sexual function after hysterectomy has not been done. It may well be that adverse effects cannot solely be attributed to hysterectomy given the above study, which included the two control groups.

percentage of women who report deteriorated sexual function after hysterectomy has not been done. It may well be that adverse effects cannot solely be attributed to hysterectomy given the above study, which included the two control groups.

Graefenberg Spot

An unknown proportion of women report that massaging the anterior vaginal wall approximately one third of the way up from the introitus causes increasingly intense sexual pleasure, arousal and may lead to orgasm. It currently is thought that it is the massaging of the periurethral erectile tissue (the equivalent of the corpus spongiosum around the male urethra in the penis) that underlies this phenomenon. There is no anatomical evidence of any structure to correspond to a specific “spot.”

Sex Hormones and Sexual Response

Androgens

The evidence for the role of testosterone in women’s sexual response is mainly indirect. Sudden loss of androgen can, in an unknown percentage of women, result in a syndrome whereby formerly useful sexual stimuli—mental, visual, or physical genital or nongenital or intercourse itself—all fail to arouse. Any former awareness of genital swelling, tingling, throbbing, and vaginal lubrication is now absent. Any former apparently spontaneous sexual thinking and desire also is lost. Clinicians report frequent association of chemotherapy-induced or surgical menopause with this syndrome. Nevertheless, other women with induced menopause report no sexual changes, and three recent prospective nonrandomized studies of women requiring hysterectomy for benign disease and electing to keep or not keep their ovaries show no deterioration in sexual function in those choosing oophorectomy. The indirect evidence is that supplementing postmenopausal estrogenized women diagnosed with hypoactive sexual desire, with testosterone such that their serum levels match or slightly exceed those of healthy young women, is associated with increased sexual response as well as increased desire.

Evidence correlating sexual function with serum androgen levels in either premenopausal or postmenopausal women with or without sexual dysfunction is lacking. There was minimal correlation between total testosterone and free androgen index (FAI) and sexual function in the study of 2,900 pre- and perimenopausal multiethnic North American women 42 to 52 years of age in the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Similarly, measures of free and total testosterone failed to correlate with sexual function in a study of 1,021 Australian women 18 to 75 years of age. In that study, a low score for sexual response for those over 45 years was associated with higher odds of having a dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS) level below the tenth percentile for this age group. However, the majority of women with low DHEAS levels did not have reduced sexual function.

At this time, research is focusing on testosterone, which is produced intracellularly (i.e., within brain and other cells from ovarian and adrenal precursors). These precursors or “prohormones” include androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) from both the adrenals and ovaries (as well as DHEAS and androst-5-ene-3β, 17β-diol from the adrenal glands) and account for at least 50% of testosterone activity in younger women; the majority of testosterone activity in older, naturally menopausal women; and close to 100% in surgically menopausal women. From the third decade on, adrenal prohormone production progressively declines such that in the 50 to 60 year-old-age group, serum DHEAS has decreased by some 70% compared with peak values of the late 20s. How much individual variation there is is not yet known. It also is difficult to measure the cellular deprivation in an individual woman: <10% spills back into the bloodstream, so serum levels of testosterone reflect mainly gonadal production. To complicate the situation further, the assays available to date for free, bioavailable, and total testosterone are not designed for the female range and have proven very unreliable. Mass spectrometry methods or equilibrium dialysis for the measurement of free testosterone are recommended but are rarely available to clinicians and have often not been chosen by researchers. Currently, metabolites resulting from the breakdown of testosterone—wherever it has been produced—can be measured. These metabolites include androsterone glucuronide (ADT-G); androstane 3α, 17β-diol glucuronide (3α-diol-G); and androstane 3β, 17β-diol glucuronide (3β-diol-G). At this time, these are available only on research basis, and age-related values in women with and without dysfunction are only now being established. Whether total androgen activity as measured by testosterone metabolites correlates with sexual function is currently under investigation. Also, the relative importance of total androgen activity needs to be compared with the importance of psychosocial variables, including the interpersonal relationship.

Estrogen

Any role of estrogen in sexual desire and arousability remains in question. One recent study showed sexual responsivity (a measure of desire and intensity of response) to be improved in Australian women receiving estrogen therapy, provided the estrogen serum estradiol levels reached between 650 and 758 pmol/L—approximately twice the level required to improve local symptoms of vaginal dryness. It is also unclear if the documented effect of supplemental testosterone to increase desire and arousability is via the androgen receptor or via the estrogen receptor after aromatization. One recent study suggests that benefit is via the androgen receptor, as the addition of an aromatase inhibitor did not reduce the benefit of supplemental testosterone. This was in a study of postmenopausal women receiving

transdermal estrogen therapy and additional testosterone to benefit loss of sexual desire. It also is possible that testosterone allows benefit mainly by reducing sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), thereby freeing estrogen to become more bioavailable.

transdermal estrogen therapy and additional testosterone to benefit loss of sexual desire. It also is possible that testosterone allows benefit mainly by reducing sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), thereby freeing estrogen to become more bioavailable.

Estrogen is necessary to maintain healthy vaginal epithelium, stromal cells, and smooth muscles of the muscularis as well as thickness of the vaginal rugae. Genes activated by estrogen and estrogen agonists include those that have a role in vascular response such as NO synthase and prostacyclin synthase. Estrogen’s beneficial effects on lipids add to estrogen’s potential vascular benefit.

The role of estrogen locally in genital tissue health requires further research. The pallor of vulvovaginal atrophy is sometimes obvious, but this does not necessarily correlate with symptoms of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia. Estrogen levels do directly correlate with the ratios between parabasal, intermediate, and superficial vaginal cells as in the maturation index. However, estrogen levels and duration of estrogen lack correlate poorly with sexual symptoms. The latter can occur perimenopausally and yet sometimes only decades postmenopause. Possibly, a confound is the permeability of vaginal epithelial cells; nerve endings containing CGRP are present in the vaginal epithelial cells and may modulate their permeability. It is of note that studies show that the prevalence of dyspareunia correlates with urinary incontinence, perceived stress, hostility, and depression as well as with vaginal dryness.

Low estrogen levels increase the pH of the vaginal lumen. There is evidence that vaginal and ectocervical cells acidify the lumen by the secretion protons across the apical plasma membrane. It is thought that this active proton secretion occurs throughout life but that it is up-regulated by estrogen. It was formerly thought that the low pH was maintained by hydrogen peroxide and protons secreted by Doderlein lactobacilli in the estrogen-replete tissues. Vaginal and urinary tract infections are more common when the pH increases, and these infections undermine women’s sexual self-confidence and contribute to dyspareunia.

Reduced sexual sensitivity of nongenital skin and the breast has received little scientific study. There is a small amount of research using pressure thresholds to demonstrate reduced vulval sensitivity postmenopause. Recently, both age and postmenopausal state have been associated with reduced vibratory sensation of the genital tract. It was also shown that age by itself affects peripheral nongenital sensation.

The pathophysiology underlying the complaint of “genital deadness,” giving rise to the syndrome known as genital arousal disorder, is unclear. Of women with this complaint, only a subgroup has demonstrably reduced genital vasocongestion in response to erotic visual stimulation. So, for some women, the genital structures are congesting apparently normally, yet their stimulation is no longer sexually arousing. Any role of reduced androgen activity awaits scientific study.

Estrogen production markedly decreases with menopause: ovarian production is minimal. The intracellular production of estrogen from testosterone, DHEA, DHEAS, and androstenedione depends on adrenal and ovarian production of these precursors, the numbers of fat cells (an important site of aromatization of testosterone to estradiol), and the activity of the appropriate steroidogenic enzymes to synthesize estrogen from the precursors in the tissue concerned. Therefore, in midlife and older women, the importance of local biosynthesis of sex hormones applies to estrogens as well as to androgens, although a reliable parameter of total estrogen activity comparable to the glucuronides identified for androgens has yet to be determined.

Estrogen-deplete states include not only post natural and surgical menopause but postpartum, in association with use of gonadotropin-releasing hormones (GnRH) agonists and some low-estrogen contraceptives, and is particularly marked in postmenopausal women receiving aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer.

Progesterone

Any role of progesterone in the sexual response of the human female remains to be clarified. Based on clinical experience, synthetic progestins may sometimes reduce sexual desire and arousability, and mood alteration may be partly responsible. Another confound is the increased SHBG when progestins are combined with estrogens in oral contraceptives. Progesterone, as opposed to progestins, has some anxiolytic properties such that increased well-being from improved sleep with associated increased sexual interest may benefit some postmenopausal women who are receiving nightly progesterone.

Dopamine

Dopamine is regarded as facilitory to sexual response and sexual desire. A small randomized controlled study of women who were not depressed but were diagnosed with hypoactive sexual desire disorder showed improvement in sexual response (but not in desire) in those receiving bupropion, a drug with both noradrenergic and dopaminergic activity. It is unknown how often anti-parkinsonian medications, which are dopaminergic, increase sexual desire in women. There is anecdotal report, but far more commonly, women with Parkinson disease complain of low sexual desire (despite medication). Although at higher doses and chronic use cocaine impairs sexual function, an acute lower dose may increase sexual pleasure, which may be via its dopaminergic activity.

Prolactin

Women with hyperprolactinemia commonly present with menstrual irregularities, infertility, and galactorrhea rather than with sexual dysfunction. Nevertheless, studies have shown that hyperprolactinemic women without depression or other hormonal disorders report lower scores for sexual desire, response, and satisfaction than do controls.

Hyperprolactinemia is sometimes associated with primary hypothyroidism that can independently decrease sexual function or with hypopituitarism such that reductions in estrogens, androgens, and glucocorticoids as well as thyroxin can be relevant.

Hyperprolactinemia is sometimes associated with primary hypothyroidism that can independently decrease sexual function or with hypopituitarism such that reductions in estrogens, androgens, and glucocorticoids as well as thyroxin can be relevant.

Sexual Dysfunction

Risk Factors

A number of factors have been shown to correlate with women’s sexual function and satisfaction, the most robust correlations being with mental health, the sexual relationship, and partner sexual function.

Mental Health

Low desire and arousal is linked not only to clinical depression but to dysthymia with lack of mental well-being associated with low self-esteem and frequent anxious and depressed thoughts. Lack of emotional well-being was one of the stronger predictors of women’s distress about sex in a recent North American probability sample. A history of past recurrent clinical depression has been found to be associated with reduced sexual arousal, sexual pleasure, and both physical and emotional dissatisfaction. This was true even when controlled for current mood, medications, marital status, and substance abuse. Unfortunately, antidepressants may further inhibit sexual response and desire, although for many women, treating their depression ameliorates their sexual difficulties. Of note, depressed women may masturbate more frequently when depressed.

Sexual Relationship

Extensive study of the psychosocial factors affecting the sexual response of 926 Swedish women 18 to 65 years of age has shown that satisfaction with the partner relationship is one of the two most prominent factors influencing presence or absence of dysfunction. Similar results stem from studies of midlife women, including those studied longitudinally across the menopause transition.

Partner’s Sexual Function

The partner’s sexual function was the second factor in the recent Swedish study that proved to have a robust association with women’s sexual function and satisfaction. Other studies have corroborated these findings, and of note, for older women, the main reason to cease sexual activity is lack of a sexually functioning partner.

Personality Factors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree