Vulvovaginal Complaints in the Adolescent

Elise D. Berlan

S. Jean Emans

Rebecca F. O’Brien

Vaginitis is a common gynecologic problem in the adolescent despite the fact that she has developed a more resistant, estrogenized vaginal epithelium; pubic hair; and labial fat pads. The striking difference between prepubertal and adolescent vaginitis is the shift in etiology. Vulvovaginitis in the prepubertal child is often nonspecific and may be associated with poor perineal hygiene, whereas vaginitis in the adolescent usually has a specific cause, such as Candida, bacterial vaginosis, or Trichomonas. Vaginal discharge may also be the presenting symptom in the adolescent with cervicitis, which may be caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, herpes simplex, or other etiologies (1). In addition to these true infections, physiologic discharge, a normal desquamation of epithelial cells secondary to estrogen effect, is a common cause of discharge in the pubescent girl. This chapter includes a description of the various causes of vaginitis as well as of vulvar disease (2,3), toxic shock, and management of the adolescent female with dysuria. Infections with N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis (4) are covered in Chapter 18, human papillomavirus (HPV) in Chapter 20, and many vulvar dermatoses in Chapter 5.

Vaginal Discharge

The evaluation of vaginal discharge in the adolescent should include obtaining a history of symptoms (pruritus, odor, quantity, color), other illnesses such as diabetes or HIV infection (5), recent oral medications such as broad-spectrum antibiotics or hormonal contraceptives, previous similar episodes of vulvovaginal symptoms, and treatments. A history of broad-spectrum antibiotics or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus is frequently a clue to the diagnosis of Candida vaginitis. Candida vaginitis and bacterial vaginosis (BV) often recur despite compliance with a standard treatment course. In a sensitive manner, the provider should inquire about sexual activity, a past history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and condom use. A patient may not disclose or remember all previous STI episodes, so it is important to check the chart or electronic medical record for evidence of prior infections. The patient should be questioned about recent sexual experiences with both men and women, since treatment failure in an adolescent girl often occurs because of reexposure to an untreated contact. Women who have sex with women are also at risk for STIs and BV related to sexual behaviors, practices, and partners (male and female) (1). It should be remembered that several infections may coexist; a patient may be adequately treated for one infection and still have a second or third infection. For example, an adolescent may have C. trachomatis cervicitis, Trichomonas vaginitis, and vulvar condyloma. In addition, the use of oral broad-spectrum antibiotics for the treatment of one type of vaginitis may be followed by a second infection with Candida.

An adolescent may have symptoms for weeks or months before seeking medical help because of anxiety about a possible pelvic examination or because of guilt or trauma from a previous episode of rape, intercourse, or sexual abuse. Therefore, it is important to explain carefully to her the details of obtaining vaginal swabs and a speculum examination (if indicated), and the possible causes of vaginal discharge.

The microbiologic flora of the adolescent vagina and cervix are shown in Fig. 17-1 (6). Assessment usually includes a visual inspection of the vulva, wet preparations of the vaginal discharge, pH, and testing for STIs as indicated. A speculum examination is usually omitted in the young virginal adolescent who has a whitish mucoid discharge. Samples for wet preparations and pH can be obtained with a saline-moistened, cotton-tipped applicator or Calgiswab gently inserted through the hymenal opening to confirm the diagnosis of physiologic discharge and exclude Candida vaginitis.

In sexually active patients, several different strategies for diagnosing vaginitis are employed. The traditional technique has been to perform a speculum examination to obtain specimens of the vaginal discharge, pH, and endocervical tests for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis (see Chapters 1 and 18). Recent studies have focused on whether vaginal complaints can be diagnosed on the basis of urine testing for N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis (and Trichomonas) (7,8), and/or provider- or patient-obtained vaginal swabs (8,9,10,11,12). Numerous studies have found that adolescent girls and women can successfully obtain vaginal samples (a Dacron swab placed 1 in. into the distal vagina for 10 seconds) and find them highly acceptable (13,14,15,16,17,18,19). Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) of vaginal swabs for detection of N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis has a sensitivity and specificity that rivals endocervical samples and is slightly superior to urine (10,13,15,20,21). Blake and colleagues found that specimens obtained with or without a speculum were equally sensitive in diagnosing vulvovaginal infections (12). Although there are many advantages to less invasive testing, the vulva, vagina, and cervix may not be visualized, missing dermatoses, condyloma acuminata, genital herpes, and cervical friability or mucopus. Symptoms are not sufficient to distinguish between etiologies, although lack of itching makes candidiasis less likely, and lack of perceived odor makes bacterial vaginosis less likely (22). Thus, careful selection of patients with symptoms of vaginitis that might be appropriate for vaginal swabs, preferably done by a provider, without a speculum examination is important. Any symptoms of abdominal pain and dyspareunia should lead to a full pelvic examination to assess the patient for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) (23).

Inspection of the vulva is often helpful in the differential diagnosis of vulvovaginitis. A small magnifying glass can be of help. A red, edematous vulva with satellite red papules is characteristic of acute Candida vulvovaginitis. Fissures and excoriations are seen with subacute or chronic Candida infections. Vulvar dermatoses, such as psoriasis (see Chapter 5), may present with red, scaly, cutaneous plaques. Small vesicles or ulcers are typical of herpetic vulvitis (see p. 313). Symptomatic gonococcal cervicitis and pelvic inflammatory disease may be accompanied

by a gray or greenish-yellow discharge from the vagina and urethra.

by a gray or greenish-yellow discharge from the vagina and urethra.

The appearance of the vaginal secretions often gives a clue to the diagnosis. A thick, curdy discharge is typical of Candida; a yellow or white, bubbly, frothy discharge can be typical of Trichomonas vaginalis. In patients with Trichomonas infections and those with cervicitis, the cervix may be friable and may bleed during collection of the samples. A cervical ectropion is present in many adolescents; large ectropions may be responsible for persistent vaginal discharge in adolescents, even in the absence of infection. Cervical ectopy has been associated with younger age, C. trachomatis, and oral contraceptive use (24).

Mucopurulent cervicitis (MPC) has been variably defined by the presence of mucopurulent discharge, quantitation of leukocytes in cervical exudate, easily induced cervical bleeding, and histologic examination of the cervix. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) identifies two major diagnostic signs of cervicitis as (a) the presence of mucopurulent secretion visible in the endocervical canal or on an endocervical swab (termed MPC) and/or (b) “sustained endocervical bleeding easily induced by gentle passage of a cotton swab through the cervical os” (1). Women with MPC may have abnormal vaginal discharge or bleeding after intercourse. Mucopus is evident if a yellow color is noted on a white cotton-tipped applicator inserted into the endocervical canal and twirled. The yellow color has been associated with C. trachomatis cervicitis in clinics that treat STIs but has a low positive predictive value (1). N. gonorrhoeae may also cause MPC, but often other infectious agents such as Trichomonas, herpes simplex virus (HSV), Mycoplasma genitalium, and BV and frequent douching may cause persistent mucopus that persists despite courses of antibiotics. Most persistent cervicitis is not caused by gonorrhea or chlamydia.

Microscopic examination of the wet preparations usually provides the diagnosis (see Chapter 1, Fig. 17-2, and Table 17-1). On the saline preparation slide, trichomonads are seen as motile flagellated organisms. Sheets of normal epithelial cells are characteristic of physiologic discharge. So-called clue cells (epithelial cells coated with large numbers of refractile bacteria that obscure the cell borders) are seen in bacterial vaginosis. The potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation is used to demonstrate the pseudohyphae of Candida. If the discharge is itchy or cheesy and yet no pseudohyphae are seen on the KOH preparation, a culture for Candida on Biggy agar is helpful.

A finding of >10 white blood cells (WBCs) per high-power field on microscopic examination of vaginal fluid may be seen in the presence of Trichomonas, to a lesser extent with Candida vaginitis, and with cervicitis (including gonorrhea and chlamydia) and PID. The presence of leukocytes in the absence of a diagnosis suggests that further tests and a follow-up visit in 2 weeks may be necessary to assess the problem. For example, the wet preparation may miss the diagnosis of Trichomonas because of a sensitivity of only 50% to 75%.

An amine fishy odor when a drop of discharge is mixed with 10% KOH is a positive “whiff” test result; it occurs most commonly with bacterial vaginosis but may sometimes occur with Trichomonas as well. The pH of the vaginal secretions is helpful in the differential diagnosis. A normal pH of <4.5 is found in patients with normal discharge and Candida vaginitis, whereas the pH is elevated above 4.5 (4.7 in some studies) in patients with Trichomonas vaginitis and bacterial vaginosis. Gram stain of the vaginal discharge (difficult to perform in the office because of regulations) can be used to identify lactobacilli, typical of normal discharge, and to detect alterations in the flora seen in bacterial vaginosis in which gram-variable coccobacilli and curved gram-negative rods are observed. Gram stain of the endocervical mucopus can be examined for increased numbers of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and the presence of gram-negative intracellular diplococci (see Chapter 18). In the sexually active adolescent with vaginal discharge, NAATs should be done to detect C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae (depending on the community prevalence) and, if available, Trichomonas.

Papanicolaou (Pap) tests are typically initiated at age 21 and are not recommended for the diagnosis of vaginitis (25). However, some findings reported on Pap test results are associated with particular infections. Herpes simplex is associated with intranuclear inclusions and multinucleate giant cells. Chlamydia has been associated with inflammation, cytoplasmic inclusions, and transformed lymphocytes or increased histiocytes. Trichomonas may be seen on Pap test, but false positives are not infrequent. The Pap test has been noted to have a sensitivity of 17% to 58% for the detection of C. trachomatis, 3% to 49% for Candida, 25% for bacterial vaginosis, 33% to 79% for Trichomonas, and 25% to 66% for herpes simplex (26,27). Fluid from liquid-based Pap tests may also be used to detect C. trachomatis (28,29,30). Multiple tests from the same specimen may be available in the future. In a study of STI clinic patients, Paavonen

and colleagues (31) found on colposcopic evaluation that endocervical mucopus was associated with N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, and herpes simplex; ulcers, necrotic areas, and increased surface vascularity with herpes simplex; strawberry cervix (uniformly arranged red spots or stippling of a few millimeters in size, located on the squamous epithelium covering the ectocervix) with Trichomonas; hypertrophic cervicitis with C. trachomatis; and immature metaplasia with C. trachomatis and cytomegalovirus.

and colleagues (31) found on colposcopic evaluation that endocervical mucopus was associated with N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, and herpes simplex; ulcers, necrotic areas, and increased surface vascularity with herpes simplex; strawberry cervix (uniformly arranged red spots or stippling of a few millimeters in size, located on the squamous epithelium covering the ectocervix) with Trichomonas; hypertrophic cervicitis with C. trachomatis; and immature metaplasia with C. trachomatis and cytomegalovirus.

Table 17-1 Clinical Findings in Common Vulvovaginal Conditions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Therapy is aimed at the specific cause. Patients should avoid douches because douching has been associated with an increased risk of STIs (32) and PID (33,34) and reduced fertility (35,36). When one STI has been detected, the clinician should

test the patient for others, including HIV and syphilis. Counseling about prevention, abstinence, safer sex, partner treatment (if diagnosis of an STI), and the use of condoms is essential. Clinicians should obtain a confidential contact number for notification of positive test results. Provision of written materials may be especially helpful. Excellent patient resources are available at www.cdc.gov and http://www.youngwomenshealth.org

test the patient for others, including HIV and syphilis. Counseling about prevention, abstinence, safer sex, partner treatment (if diagnosis of an STI), and the use of condoms is essential. Clinicians should obtain a confidential contact number for notification of positive test results. Provision of written materials may be especially helpful. Excellent patient resources are available at www.cdc.gov and http://www.youngwomenshealth.org

In addition to medical treatments outlined in the next sections, general therapies for significant vulvitis may include the following:

Warm baths once or twice a day (baking soda may be added if the vulva is irritated). Only bland soaps or Cetaphil cleanser should be used.

Careful drying after the bath and application of a small amount of baby powder (no talc) to the vulva.

Frequent changes of white cotton underpants or panty shields to absorb the discharge.

Good perineal hygiene (including a suggestion, albeit not evidence based, of wiping from front to back after bowel movements).

Avoidance of bubble bath or other chemical irritants.

Physiologic Discharge

Agent

A normal estrogen effect.

Symptoms

A whitish mucoid discharge that usually starts before menarche and may continue for several years. With the establishment of more regular cycles, the adolescent may notice a cyclic variation in vaginal secretions: copious mucoid or watery secretions at midcycle and then a stickier, scantier white discharge in the second half of the cycle associated with rising progesterone levels.

Diagnosis

The wet preparation reveals epithelial cells without evidence of inflammation.

Treatment

Most health classes that discuss puberty and menarche do not include an explanation of the change in vaginal secretions. The clinician can reassure the patient by explaining vaginal physiology and can suggest measures to help if she is bothered by the discharge—baths, cotton underpants, and, as needed, some form of panty shield that she can change frequently. If an older adolescent is troubled by excessive discharge, especially during jogging or athletics, evaluation of the cervix and vagina may be indicated. The use of a conventional tampon (not a superabsorbent tampon) during athletics for a few hours on 1 or 2 days at midcycle can help the adolescent who is troubled by heavy discharge. It is extremely important that she not be overtreated with vaginal creams and given the impression that the physiologic discharge represents an infection. It is also important to discourage the daily use of tampons because of the possibility of vaginal ulcers and exacerbation of the discharge.

Trichomonal Vaginitis

Agent

Trichomonas vaginalis, a small, motile, flagellated parasite.

Symptoms

Frothy, malodorous, yellow, yellow–green, or white discharge that may cause itching, dysuria, postcoital bleeding, dyspareunia, or any combination of these symptoms. May be asymptomatic and found on culture, Pap test, wet preparation, NAAT, or other diagnostic tests (37,38,39,40). Trichomonas infects the vagina, urethra, and Skene and Bartholin glands.

Source

Usually sexually acquired. Males are usually asymptomatic or have urethritis, but may reinfect the female after she is treated. Since Trichomonas may survive for several hours in urine and wet towels, the possibility of transmission by sharing wash cloths has been suggested but not proved; it is unlikely to occur frequently, given the association of this infection with other sexually transmitted diseases. The incubation time has been estimated to be between 4 and 20 days with an average of 7 days. The prevalence of Trichomonas in a nationally representative U.S. sample of adolescents ages 14 to 19 years was 2.5% overall, and 3.6% in sexually experienced adolescents (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES] 2003–2004) (41). In some populations infection rates are higher. For example, in a cohort of 268 adolescent women ages 14 to 17 years followed for up to 27 months by vaginal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests in a clinic setting, 6% were infected at enrollment and 23% became infected during the course of the study (42). In a study of 107 young black women followed for 1 year with cultures, the incidence was 7.4%, higher than chlamydia in this group (4.4%) (43). A recent study of incarcerated women ages 18 to 25 years found a 26% prevalence of T. vaginalis (44). Bacterial vaginosis and Trichomonas vaginitis may occur simultaneously, and Trichomonas facilitates the growth of anaerobic bacteria.

Diagnosis

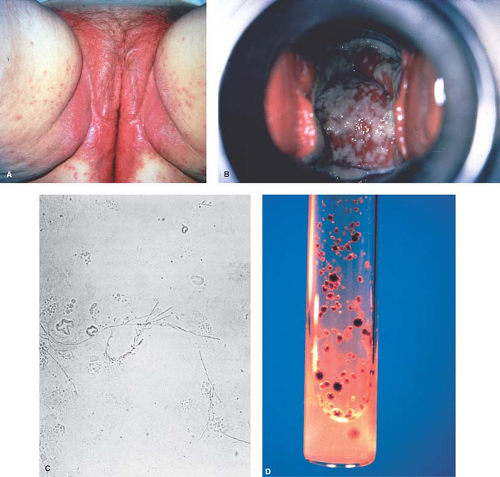

The vulva may be erythematous or excoriated, with a visible discharge evident on inspection (Fig. 17-3A). The classic yellow–green discharge is seen in 20% to 35% of patients; more often the discharge is gray or white. A frothy discharge is seen in about 10% of women and may also occur with bacterial vaginosis. Grossly visible punctate hemorrhages and swollen papillae (strawberry cervix) are seen in only about 2% of patients (15% of an STI population evaluated by colposcopy) (Fig. 17-3B). By colposcopy, this special finding had a 45% sensitivity and a 99% specificity for Trichomonas (31). Like bacterial vaginosis, vaginal pH is elevated in Trichomonas.

The traditional and most widely used method is the saline wet preparation, which may show flagellated organisms moving under the cover slip along with an increase in the number of leukocytes, which can be visualized using both the low and high power of the microscope. The vaginal wet mount has low sensitivity but high specificity when compared to the “gold standard” of culture (28,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52). The vaginal wet mount detects 64% of infections in asymptomatically infected women, 75% of those with clinical vaginitis, and 80% of those with characteristic symptoms. Philip and co-workers (48) found that the wet mount gave a positive result only in patients whose cultures had >105 colony-forming units/mL. The combination of wet mount and spun urine has a sensitivity of 85% compared to 73% for the vaginal wet mount alone (52). The sensitivity of culture methods such as Diamond and Holander is higher (95% to 96%), as are tests such as direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) (85%), PCR (89% to 100%), and enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (82%) (8,37,49,50,51,52,53). The office-based InPouch TV culture method also has higher sensitivity (84%) than the wet mount (40,50,51). PCR has higher detection rates for vaginal samples than urine samples (9,53).

There are two point-of-care tests for Trichomonas for offices without microscopy. A nucleic acid probe test, Affirm VP III

(Becton Dickenson), assesses Trichomonas (as well as BV and Candida) in 45 minutes and is 80% to 90% sensitive and 99% specific compared with wet mount for Trichomonas. Comparisons to culture or NAAT (39,54) are needed and thus its true sensitivity is likely lower. A rapid point-of-care antigen test that detects T. vaginalis membranes in about 10 minutes (OSOM Trichomonas Rapid Test, Genzyme Diagnostics) has a sensitivity of 83% to 90% and specificity of 100% when compared to culture (55,56). False positives can occur, especially in low-prevalence populations. Several nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs)—PCR (Amplicor, Roche) and RNA transcription-mediated amplification tests (Aptima, Gen-Probe, Inc.)—used for gonorrhea and chlamydia detection can also detect Trichomonas (with appropriate laboratory equipment) with high sensitivity (74% to 98%) and high specificity (87% to 98%) and had better performance on vaginal than urine samples (1,56,57,58,59). Thus, besides microscopic examination of vaginal secretions at the bedside, NAATs are the most promising tests for diagnosing Trichomonas infections in clinical settings.

(Becton Dickenson), assesses Trichomonas (as well as BV and Candida) in 45 minutes and is 80% to 90% sensitive and 99% specific compared with wet mount for Trichomonas. Comparisons to culture or NAAT (39,54) are needed and thus its true sensitivity is likely lower. A rapid point-of-care antigen test that detects T. vaginalis membranes in about 10 minutes (OSOM Trichomonas Rapid Test, Genzyme Diagnostics) has a sensitivity of 83% to 90% and specificity of 100% when compared to culture (55,56). False positives can occur, especially in low-prevalence populations. Several nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs)—PCR (Amplicor, Roche) and RNA transcription-mediated amplification tests (Aptima, Gen-Probe, Inc.)—used for gonorrhea and chlamydia detection can also detect Trichomonas (with appropriate laboratory equipment) with high sensitivity (74% to 98%) and high specificity (87% to 98%) and had better performance on vaginal than urine samples (1,56,57,58,59). Thus, besides microscopic examination of vaginal secretions at the bedside, NAATs are the most promising tests for diagnosing Trichomonas infections in clinical settings.

Pap tests have a detection rate of only 50% to 86%, and false-positive results can occur with conventional Pap tests (45). If asymptomatic women are treated only on the basis of a positive Pap test, 20% to 30% may be treated unnecessarily (45,47). When the prevalence in the clinical population of Trichomonas is 10% or less, a positive Pap test should be confirmed with culture or other more sensitive test. If the prevalence is ≥20%, then treatment is suggested (45). Liquid-based Pap tests appear to provide higher sensitivity (61%) and specificity (99%) in an adult population with a prevalence of 21% (60). Monoclonal antibody staining has been reported to detect 86% of positive specimens, including 92% of those with positive wet mounts and 77% of those missed on wet mount (37).

Treatment

Metronidazole 2 g or tinidazole 2 g orally all in one dose is effective in 86% to 95% of patients, with tinidazole the same or superior to metronidazole (1). The sexual partner should be treated with the same dose at the same time. Patient-delivered partner therapy (PDPT) may have a role in reducing reinfection but data on efficacy are not as evident as for chlamydia or gonorrhea (1). The side effects of metronidazole include nausea, vomiting, headache, metallic aftertaste, and rarely blood dyscrasias. The patient should be instructed to avoid alcohol during her treatment (and 24 hours after metronidazole and 72 hours after tinidazole) and intercourse until both partners have been treated. If the clinician is unable to provide treatment for the partner, the partner can be referred to his own clinician. Rescreening for recurrent infection in 3 months can be considered.

If the organisms persist in the vagina after single-dose metronidazole, and if reinfection is not the cause, a longer course of metronidazole (500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days) or tinidazole can be prescribed (1). The 7 day course of metronidazole is also more effective than single dose in patients with HIV infection, and treatment reduces HIV shedding (1). Recurrent infection necessitates re-treating the partner(s) each time and making sure the relationship is monogamous; otherwise, the patient should understand the futility of repeated treatment. In an urban gynecology clinic in Atlanta, 2.4% of the isolates showed low-level in vitro resistance; all treated women who returned for repeat examination had cleared the infection (61). Rarely, a patient will have a Trichomonas infection that has relative resistance to metronidazole and is refractory to treatment (62,63). The patient can be treated with 2 g per day of metronidazole orally or tinidazole 2 g orally for 5 days. Patients not responding to the regimen should be managed in consultation with an expert (such as the CDC), and the susceptibility of the Trichomonas to metronidazole should be determined (1). Lossick and colleagues (62) reported the need for an average oral dose of 2.6 g per day of metronidazole for a mean period of 9 days to cure refractory Trichomonas. Neurologic side effects are common if >3 g is taken orally in a day. A complete blood count should be done before prolonged therapy is undertaken.

Candida Vaginitis

Agent

Symptoms

Thick, white, cheesy, pruritic discharge. The vulva may be red and edematous. Itching may occur before and after menses and, in some patients, seems to remit at midcycle. Patients may experience dyspareunia with an increase in symptoms after intercourse. Many patients have external irritation and dysuria.

Source

The predisposing factors to Candida vaginitis include diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, antibiotics, corticosteroids, obesity, and tight-fitting undergarments. The frequency of positive cultures rises from 2.2% to 16% by the end of pregnancy. The increase in clinical infections appears to be associated with the rise in pH that occurs in late pregnancy as well as premenstrually (67). Infections are more common in the summer. Candida may occur as part of the normal flora in 10% to 20% of women; eradication of Candida as determined by culture, however, may be important in patients with frequent recurrences. While recurrent Candida vaginitis occurs in women with HIV disease, vulvovaginal Candida infections are so common in normal women that it is not a specific indication for HIV testing in those previously testing negative (1). Candida is not seen more commonly in STI clinics than in other settings, and sexual transmission rarely plays a role (68,69). Males may have symptomatic balanitis or penile dermatitis.

Diagnosis

The vulva is usually red and may be edematous, with small satellite red papules or fissures at the posterior fourchette (Fig. 17-4A). The vaginal discharge may show a white cheesy discharge (Fig. 17-4B). The KOH preparation shows yeasts, hyphae, or pseudohyphae in 80% to 90% of symptomatic patients (Fig. 17-4C). However, C. glabrata is not as easily recognized because it does not form hyphae or pseudohyphae. Vaginal pH is normal (4.0 to 4.5) in vulvovaginal candidiasis. In patients with suggestive signs or symptoms and especially in patients previously labeled as having recurrent or persistent Candida infections, it is important to obtain specimens for wet preps and culture from the vagina before more aggressive therapy is undertaken. The easiest office culture medium is Biggy agar, which can be read for the presence of brown colonies after 3 to 7 days of incubation (Fig. 17-4D). Sabouraud agar can also be used. Most patients with symptomatic infections have a large number of colonies; however, even a few colonies may be significant in the woman with frequent infections who has recently finished a treatment course. In cases difficult to diagnose, the patient may be shown how to inoculate a culture at home with a cotton-tipped applicator when her symptoms increase. However, as noted above, because normal women can have Candida species, a positive culture in the absence of symptoms or signs is not an indication for treatment.

Treatment

The options for therapy include intravaginal preparations and oral agents. The azoles are the mainstay of intravaginal treatment. Courses of therapy range from a single dose to 3 to 7 days of therapy with creams or suppositories for uncomplicated infections (mild to moderate, sporadic, normal host, susceptible C. albicans). Complicated infections include severe local infections; recurrent infections [four or more episodes in 1 year; an abnormal host, (such as diabetes, debilitation, immunosuppressed, or pregnant); or a less susceptible pathogen such as C. glabrata and require 10 to 14 days of topical azoles, a multidose course of an oral azole, or alternative therapies (see below) (1,70,71,72,73,74,75). The suppositories are less messy than creams but may not treat vulvar infection as well. The symptomatic male partner can use the cream as well. Some packaging contains both suppositories and cream (e.g., Monistat Dual-Pak, Gyne-Lotrimin Combination Pack). The efficacy of treatment, as judged by symptomatic improvement and negative cultures after any of the available treatment courses with azoles, is approximately 85% to 90% at the end of therapy and 70% to 80% 3 weeks later. Allergic symptoms to the azoles are often manifested by increased burning and itching after several days of therapy. Nystatin is probably less effective because it requires the patient to comply with 2 weeks of therapy; however, it is useful in women who develop allergic symptoms to the azoles.

Treatment doses are as follows (presented alphabetically within categories of over-the-counter and prescription, which continue to change) (1):

Over-the-counter intravaginal agents*:

Butoconazole, 2% cream, one applicatorful (5 g) for 3 nights*

Clotrimazole, 1% cream, one applicatorful (5 g) for 7 to 14 nights

Clotrimazole, 2% cream, one applicatorful (5 g) for 3 nights

Miconazole, 2% cream, one applicatorful (5 g) for 7 nights

Miconazole, 4% cream, one applicatorful (5 g) for 3 nights

Miconazole, 200-mg vaginal suppository for 3 nights

Miconazole, 100-mg vaginal suppository for 7 nights

Miconazole, 1200-mg vaginal suppository for 1 day

Tioconazole, 6.5% ointment, one applicatorful (5 g) for 1 night*

Prescription intravaginal agents*:

Butoconazole, 2% cream (5 g) (bioadhesive product), for 1 night

Nystatin, 100,000-unit vaginal tablet for 14 nights

Terconazole, 0.4% cream, 1 applicatorful (5 g) for 7 nights

Terconazole, 0.8% cream, 1 applicatorful (5 g) for 3 nights

Terconazole, 80-mg vaginal suppository for 3 nights*

Oral agent:

Fluconazole, 150-mg tablet orally in a single dose

Oral therapy with fluconazole 150 mg given as a single dose has the same efficacy as 3- and 7-day courses of the azole antifungal topical agents (1,72). For severe infections, two doses of fluconazole 150 mg can be used 72 hours apart, and for complicated infections, fluconazole can be given on days 1, 4, and 7. The reported adverse effects of oral therapy have included headache (13%), nausea (7%), and abdominal pain (6%); rare cases of angioedema, anaphylaxis, and hepatotoxicity have been reported. The important drug interactions include those with terfenadine, rifampin, astemizole, phenytoin, cyclosporin A, tacrolimus, warfarin, protease inhibitors, oral hypoglycemic

agents, calcium channel antagonists, theophylline, and trimetrexate (1). In contrast, the primary side effects of topical agents are local burning and dysuria. Most patients may prefer the ease of a single oral dose but should be counseled about the risks and benefits.

agents, calcium channel antagonists, theophylline, and trimetrexate (1). In contrast, the primary side effects of topical agents are local burning and dysuria. Most patients may prefer the ease of a single oral dose but should be counseled about the risks and benefits.

The optimal treatment for C. glabrata is not well defined. First-line therapy is a nonfluconazole azole drug (oral or topical); topical boric acid capsules have been recommended for recurrences. A small study found topical boric acid (600 mg powder in a gelatin capsule administered intravaginally once daily for 14 days) to yield a moderate success rate in women with C. glabrata (1,70). A study of diabetic women in whom C. glabrata was isolated in 61% of women found that the mycologic cure rate was higher with a 600-mg boric acid suppository for 14 days (63.6%) as compared to 150-mg single-dose fluconazole (28.6%) (71).

Only topical agents should be used during pregnancy (for significant symptoms). Treatments that have been studied for use in the second and third trimesters include clotrimazole, miconazole, butoconazole, and terconazole. Absorption is negligible with tioconazole and clotrimazole and does not occur with nystatin (1). Pregnant patients should be treated for 7 days.

Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, defined as four or more symptomatic episodes annually, can be very difficult to treat. The most important issue is to make sure that the diagnosis is in fact C. albicans because patients may have inflammation of the minor vestibular glands, HPV infection, or allergies to soaps, spermicides, or rarely semen. Once the diagnosis of Candida has been confirmed, the clinician should check for predisposing factors such as diabetes. Looser-fitting clothing and nondeodorized panty shields can be recommended. Douching equipment should be discarded. The potential for a gastrointestinal reservoir in the patient or partner should be considered. In addition, the patient may not have purchased the medication because of cost or may not have finished the previously prescribed dosage. In adolescents with recurrent Candida infections and risk factors, HIV infection should be considered.

Patients who have experienced frequent recurrences of Candida vulvovaginitis can be treated for 6 months. The course is typically initiated with either 7 to 14 days of topical antifungal therapy or a total of 3 doses of oral fluconazole 150 mg given over 1 week, on days 1, 4, and 7. This initial week of therapy is followed by oral fluconazole (100 mg, 150 mg, or 200 mg) weekly for 6 months. If this is not tolerated or feasible, then one of the topical azole vaginal agents can be tried once a week (“always on Sunday”). Alternatively, an antifungal vaginal cream can be used for 2 to 3 days before and after each menses or

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree