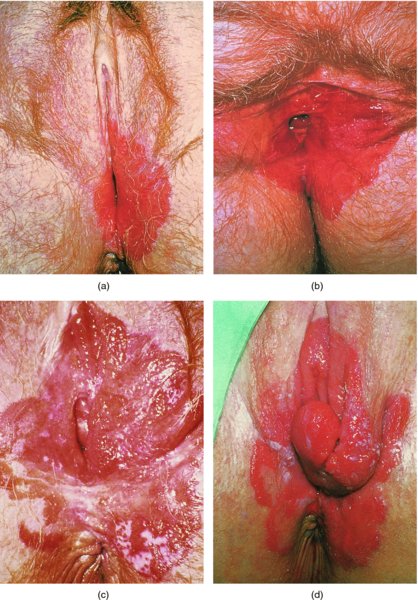

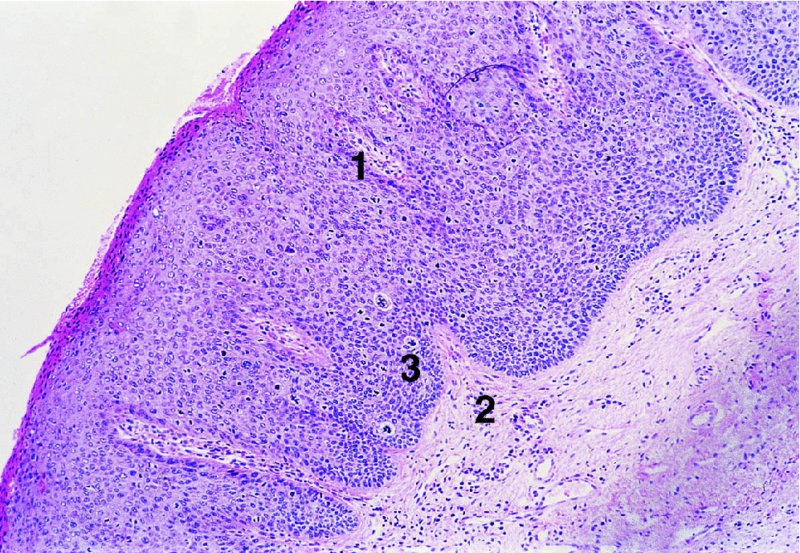

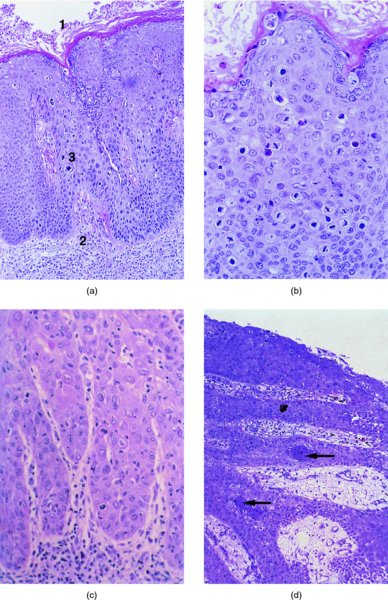

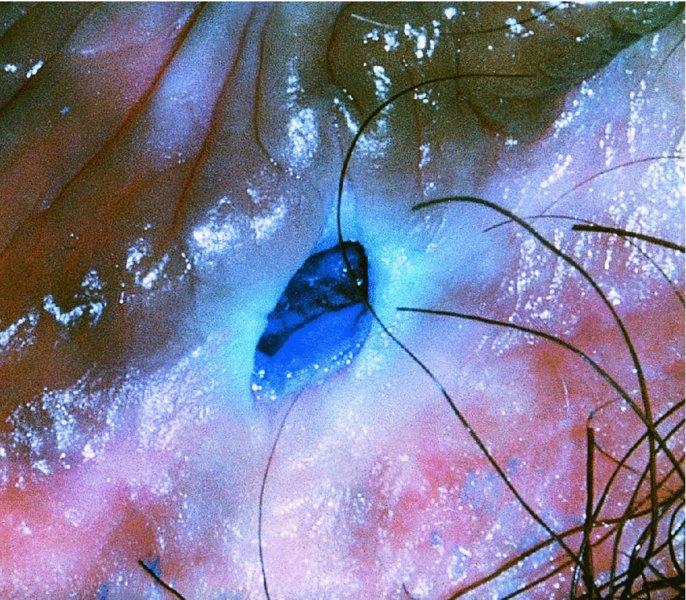

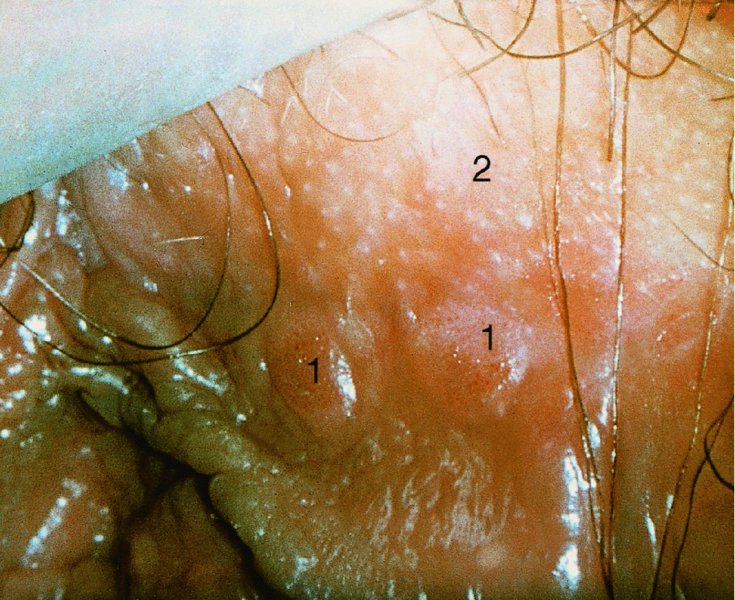

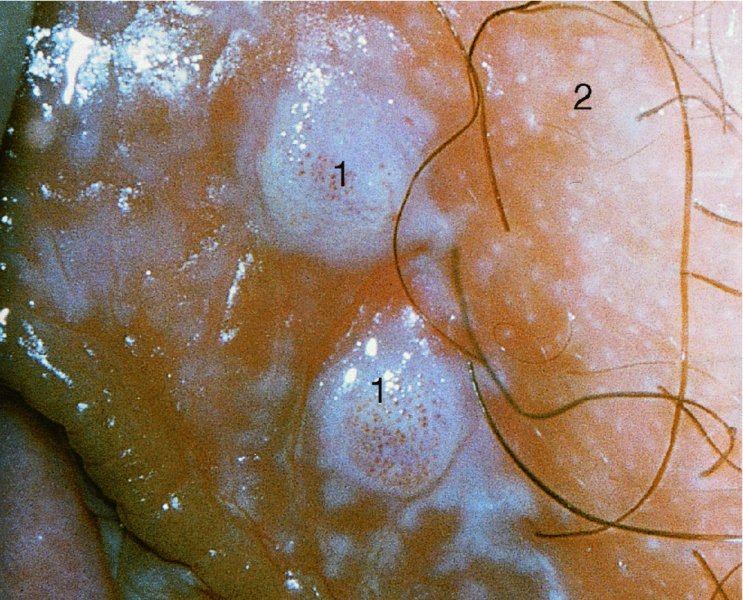

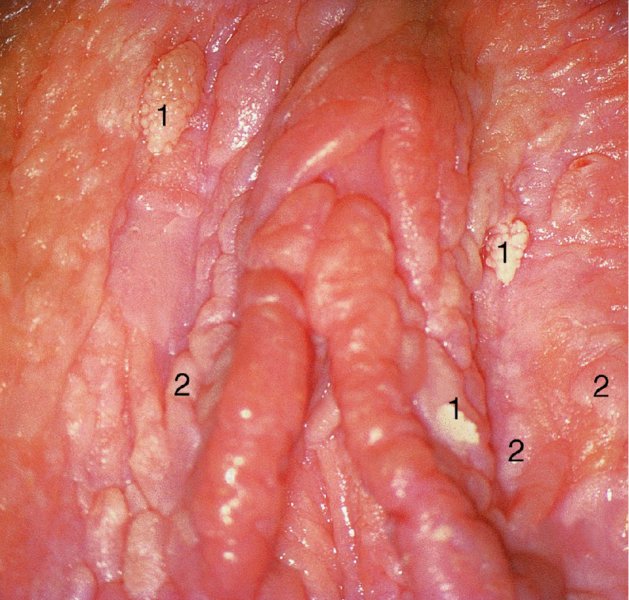

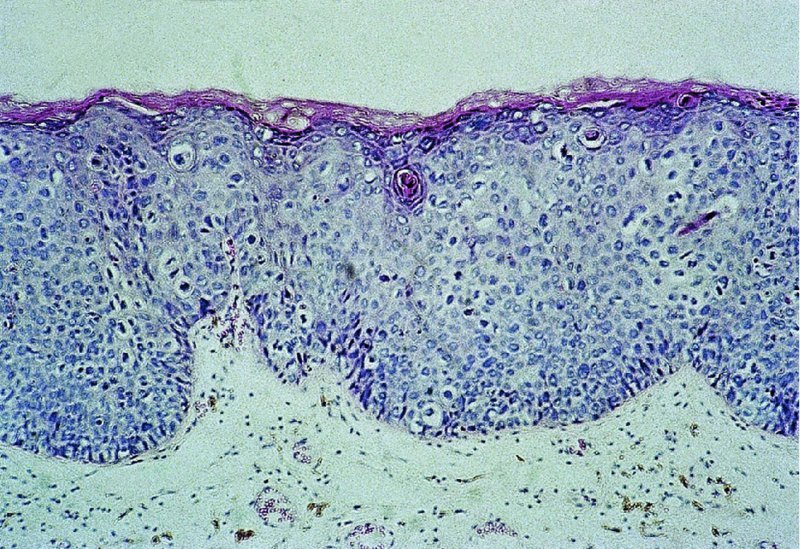

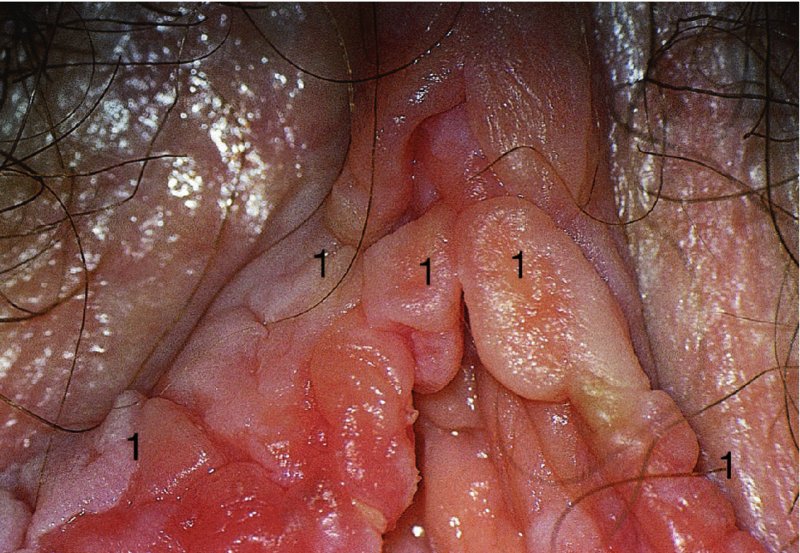

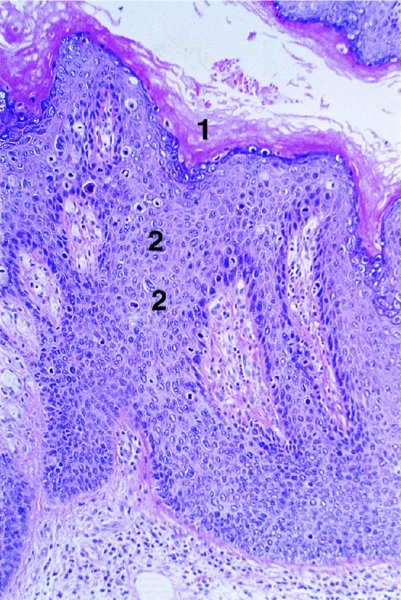

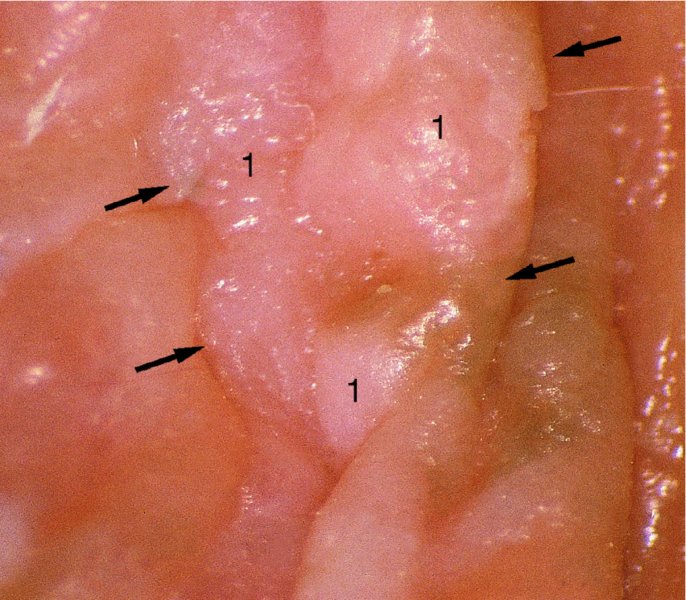

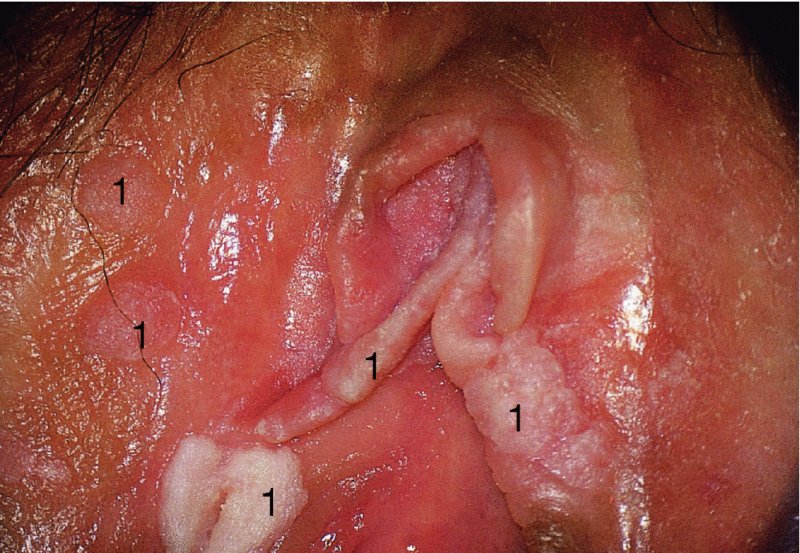

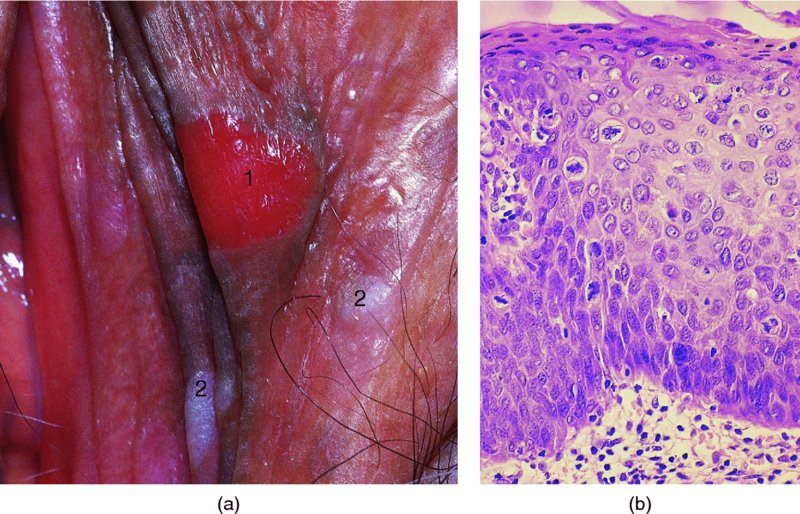

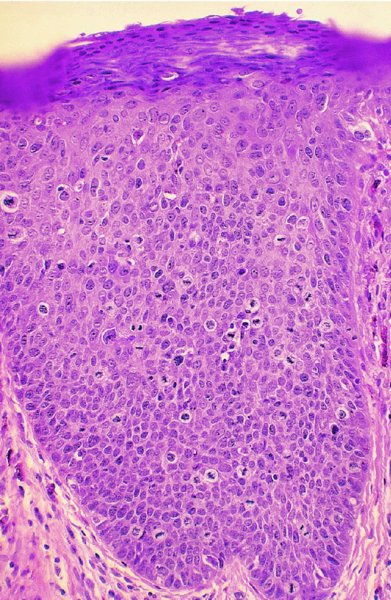

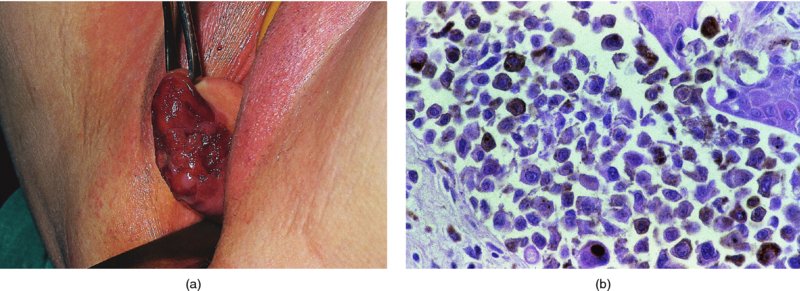

CHAPTER 9 The concept of intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva has been with us since its description in the early part of the last century. In recent years an increasing awareness of the characteristics of vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) has developed, as more information on the epidemiology, pathology, and clinical management has come to light. One of the most important developments of recent years has been the introduction of a revised classification of the condition, as a result of the 2004 recommendations of the committee on nomenclature of the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) (Table 9.1). This was confirmed by the committee on histological classification of vulval tumors and dystrophies of the International Society of Gynaecological Pathologists. These august bodies advocate usage of the term VIN, which in 1987 had been recommended to replace the very wide range of somewhat confusing terms that have been used in the past; these include Bowen’s disease, leukoplakia, Bowenoid papulosis, squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and hyperplastic dystrophy. Table 9.1 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) and International Society of Gynaecological Pathologists (ISGYP) classification In the 2004 reclassification, VIN was divided into two categories, namely usual and differentiated. The usual type had three subdivisions, namely (i) warty type, (ii) basaloid type, and (iii) mixed (warty/basaloid). The reasons behind this new classification were the universal realization emanating from many clinical studies that VIN1 was not a cancer precursor, nor was it part of the neoplastic spectrum of progressive epithelial change. Finally there was consensus that VIN1 did not need to be treated, and therefore did not need to be recognized as a subgroup of VIN. All lesions now classified as VIN should be regarded as high grade, previously being classified as VIN2,3. As will be discussed below, the usual type is mainly associated with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types whereas the differentiated type is not associated with HPV and further is found adjacent to keratinizing vulval cancer with lichen sclerosus present in many cases. Also it was felt that the terms “usual” and “differentiated” were universal terms and easily understood. VIN is characterized in a similar way to its cervical counterpart, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), in that both are made up of neoplastic cells that are confined by the boundaries of the epithelium. It is also recognized that VIN, like the higher grades of CIN, may, if untreated, progress to invasive cancer of the vulva. In addition, VIN has been known to regress spontaneously (discussed in detail below). It is difficult to be certain of the prevalence or incidence of VIN in a population because, to date, there have been no organized screening programs for the identification of these conditions. However, some studies reported an increase of vulval squamous cell carcinoma in younger women, who tend to have a history of HPV and VIN. The incidence of usual VIN, differentiated VIN, and vulval squamous cell carcinoma in the Netherlands during a 14 year period has shown that the incidence of usual VIN almost doubled from 1.2/100 000 patients in 1992 to 2.1/100 000 in 2005, and that of differentiated VIN increased ninefold from 0.013/100 000 patients to 0.121/100 000, while the incidence of vulval squamous cell carcinoma remained stable. The incidence of invasive vulval squamous cell carcinoma increases with age and a higher rate of vulval squamous cell carcinoma has been observed in white women than in women of other races. The stationary invasive cancer rate in respect of the rise in premalignant rate may be explained by the fact that transformation of HPV infection into malignant disease might take years. Other explanations offered might be that HPV preinvasive lesions very seldom develop into invasive cancer, but remain as an in situ lesion or, indeed, disappear. Studies show that VIN3 (now classified as VIN) lesions have a malignant potential as approximately 3.4% seem to progress to cancer, even when treated. The association between VIN and CIN is close. Multicentric disease of the cervix and vulva, and occasionally of the vagina, is well demonstrated (Figures 9.1, 9.2). In Figure 9.1, a 48-year-old woman had not only VIN (1) but also similar intraepithelial disease of both the cervix and the vagina. The 27-year-old woman whose vulval and perianal area is pictured in Figure 9.2 had both intraepithelial and early invasive disease affecting the cervix, vagina, and vulval (1) and perianal (2) areas. She was not immunocompromised but was an extremely heavy smoker and had a long history (>10 years) of genital tract HPV infection. Indeed, condyloma acuminata can still be seen on the vulval (3) and perianal (4) areas. The frequency of multicentricity decreased significantly with age, and patients with multicentric disease (involving the vagina and/or cervix in addition to the vulva) had a significantly higher frequency of multifocal disease, involving more than one location on the vulva, and of recurrent disease than did patients without multicentric disease. The condition may be either synchronous or metachronous. It is therefore important that all patients with vulval disease should be included in standard cervical screening. Detailed visual inspection should be performed and any suspicious lesions biopsied. The age range of patients developing VIN is very wide; some patients are as young as 15 years and others as old as 90 years. In most series the mean patient age for developing VIN is the early thirties. There can be about a 30 year difference in mean age between the precancerous (VIN) and cancerous forms of the disease. The usual type of VIN is associated with a viral etiology whereas differentiated VIN and some invasive vulval cancers have a non-viral etiology. With current techniques of HPV detection by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), it has been shown that the presence of oncogenic high-risk HPV types in usual VIN ranges from 72% to 100%, with the majority of these being HPV type 16. Usually HPV-positive women are younger than their HPV-negative counterparts. Histologically, the warty (Bowenoid) lesions contain more evidence of viral infection than the basaloid VIN lesions (65% compared with 30%). The chance of progression of VIN to carcinoma is higher in women who possess HPV type 16 and type 18 in their initial and later lesions. VIN seems to affect two patient populations: those with coexistent HPV are usually younger and have multifocal disease, and those with a variable history of HPV infection are older and inclined to have unifocal disease. The possibility therefore exists that there may be separate genetic processes involved in the development of VIN in younger women and the development of VIN and cancer in older women. It is now recognized that vulval carcinoma exists in two categories: (i) a keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma, which is the classic morphologic type that is rarely associated with HPV and predominates in older women, and (ii) a warty or basaloid cancer, which is usually HPV-related, found in younger women, and is often associated with VIN, predominating in those who are smokers and in the immunosuppressed, who also have a high rate of associated cervical neoplastic lesions. There does appear to be a strong relationship between certain sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and VIN. The most commonly associated STDs are condylomata acuminata, herpes simplex, gonorrhea, syphilis, trichomoniasis, and bacterial vaginosis. Indeed, a demographic study showed that females with vulval cancer reported having had a greater number of sexual partners than did controls and the risk of vulval cancer was elevated among women who reported a prior history of condyloma or gonorrhea. Females who were seropositive for herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV2) can be also at greater risk for VIN3 (relative risk (RR) = 2). HPV may play a role in the development of vulval cancer. It may well be the case that the lesser grades of VIN are simply another clinical condition associated with sexual activity in younger patients. It is now accepted that past infection with sexually transmitted agents other than HPV may be no more than surrogate markers of exposure to HPV, and of no separate etiologic significance. There is an increased risk of development of VIN in immunosuppressed patients, such as those undergoing renal transplantation or those with lymphoproliferative disorders or systemic lupus erythematosus. It was alluded to above that there was an increased risk of development of VIN in immunosuppressed patients. Since 1989, women with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection have been known to have a high incidence of cervical neoplasia, as described in Chapter 7. However, it is now becoming obvious that there is an increased risk of the development of intraepithelial vulval neoplasia in this group, especially those with a simultaneous HPV infection. In 1993 the first report was published of a case of multiple primary gynecologic neoplasms in association with HIV, detailing the 5 year history of a young woman with simultaneous microinvasive carcinoma of the cervix and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva. Since that time, a number of studies have pointed up the increased risk of HIV in association with VIN3. The prevalence of vulvovaginal condyloma can be increased in women with HIV positivity and in this group a small number of high-grade VINs also exist. Women who are HIV infected or under iatrogenic immunosuppression are at higher risk of developing VIN3 lesions as well as an increased number of cervical precancers and cancers. The cervical and Bowenoid/basaloid vulval neoplasias (now grouped as usual type) seem to have a similar HPV-related origin and this may be indicative of some malfunction of the cellular immune response, which appeared to be a cofactor in the genesis of HPV-associated neoplasia in both cervix and vulva. The extent of the prevalence of VIN in the HIV population is still difficult to determine, but a retrospective study of 38 HIV-infected women who were screened with colposcopy showed that 14% of them had VIN on biopsy and an additional 50% had abnormal Papanicolaou smears with 24% having biopsy evidence of CIN. This study showed the relatively high prevalence of VIN in HIV-infected women. As with CIN, smokers appear to be at higher risk for the development of VIN and invasive cancer of the vulva. A number of studies suggest that this increased risk may be as a result of or mediated through a reduced immunosurveillance mechanism that exists in women who are habitual smokers. The relationship between VIN and invasive vulval cancer is far from clear and this makes difficult any consideration of the natural history and subsequent recommendations for the management of VIN. The problem with many of the studies of VIN that purport to show progression to malignancy is that the follow-up is of patients who have already been treated, and as such one would not expect to find progression. However, in the study by Jones and McLean in 1986 from New Zealand who followed the patients in the study of Professor Green in the 1960s and 1970s who were left untreated with VIN, there was progression in four out of five of these untreated patients who had high-grade VIN and were followed over a period of 7–8 years (Figure 9.3a–d). Figure 9.3 The series of four photographs, courtesy of Dr Ron Jones of Auckland, New Zealand, showing the development of invasive cancer over a 4 year period from an obvious vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) lesion. (a) Vulva (April 1972) shows a red lesion on the labia minora and posterior labia majora. (b) By December 1973, the lesion has enlarged and biopsy shows the presence of VIN. (c) By January 1975, biopsy reveals the presence of VIN and possibly early invasive disease. (d) By September 1976, obvious cancer has developed and the full progression from an intraepithelial lesion to a malignant lesion can be seen. The considerable spatial disparity between the peak incidence of VIN (35 years) and the peak incidence of invasive carcinoma of the vulva (68 years) leads to the conclusion that these two conditions may not be directly related in all circumstances. It is also noted that VIN is commonly multifocal, whereas cancerous conditions of the vulva in the older patient are most frequently unifocal. When cancer occurs in younger women, it tends to be multifocal, suggesting development from VIN3 and an association with HPV. It is clear that the behavior of VIN does not seem to be comparable to that of CIN3; progression to malignancy is considered to be low. A smaller percentage (2–4%) of women can still develop invasive disease after successful treatment by local excision or simple vulvectomy. Spontaneous regression of VIN3 occurs: the rate is quoted as between 10% and 38% in patients under 35 years and particularly in those who have multifocal or pigmented lesions or who are pregnant. It has been reported that up to 80% of patients in whom regression occurred were pregnant at the time of diagnosis. These lesions were definitely intraepithelial neoplasia and aneuploid but, on regression, reverted to a normal ploidy pattern. It has been shown that aneuploid VIN3 lesions have an increased risk of progression to cancer and a reduced chance of spontaneous regression. The difficulty of extrapolating this natural history to management protocols is made all the more problematic by the finding of occult invasive disease in biopsies that are obtained at the time of surgical treatment in cases in which the initial diagnosis had shown only VIN. Indeed, early stromal invasion of the vulva may be more common than is suspected. The incidence of occult invasion at the time of excisional treatment shows a range of 6–9.5%. In the majority of cases, the invasive lesion was of an “early” squamous cell carcinoma with a depth of invasion less than 5 mm. It would therefore seem prudent, in view of the limited risk of progression, for treatment protocols to favor conservative methods, but emphasis should be placed on excisional techniques that allow histologic material to be obtained, so as to avoid missing the presence of occult invasive disease. Evidence from different studies suggests that the risk of invasion may be higher than had previously been anticipated and, although conservatism has been advocated, the risk of missing an occult lesion must be always considered. Histologically, VINs contain an exaggeration of the epithelial proliferations (acanthosis) that lead to minute excrescences appearing on the surface of the epithelium. These are represented clinically by the papillary or granular surface of the VIN lesions. Also exaggerating the clinical appearance is the hyper- and parakeratosis that is normally associated with these lesions and which accounts for the increased white color tone. The cell nuclei are hyperchromatic and demonstrate a loss of organization, maturation, and cohesion. Mitotic figures are generally numerous and abnormal forms are often present. Less commonly, the neoplastic cells may be uniform, but usually they are multinucleate, pleomorphic, and contain agglutinated nuclear DNA—the so-called corps ronds. In many of them there is also evidence of HPV infection with koilocytosis; the cells demonstrate cytoplasmic cavitation and nuclear atypia, as well as cytoplasmic keratinization, the so-called dyskeratosis. Abnormalities of maturation and disturbances of the normal cellular stratification are characteristics of atypia within vulval squamous epithelium. Two basic morphologic types of VIN are seen. One involves the proliferation of basal- or parabasal-type cells that extend into the upper layers of the epidermis; the so-called basaloid VIN. The other type, characterized by premature cellular maturation, often occurring in association with epithelial multinucleation, corps ronds, and koilocytosis, is a hallmark of papillomavirus infection. This second type is called warty–type VIN, previously being referred to as Bowenoid VIN. In both the basaloid and warty types, now part of the usual type, all the characteristics of abnormal and bizarre mitotic figures can be found, as can cellular and nuclear pleomorphism, irregular clumping of nuclear keratin, and either parakeratosis or hyperkeratosis. Not surprisingly, the warty-type VIN is common in women with current or previous wart viral infections of the vulva. It is not unusual for both patterns of VIN to coexist. Figures 9.4 and 9.5a,b, which are typical examples of the histology of VIN, show VIN with the characteristic loss of architecture, superficial hyperkeratosis of varying degree, marked nuclear and cytoplasmic pleomorphism, altered maturation, hyperchromic nuclei and abnormal mitotic figures, and corps ronds. Very hypertrophic and somewhat acanthotic rete ridges are commonly found (Figures 9.4, 9.5a), although it is not uncommon to observe a uniform band of pleomorphic cells extending from the surface epithelium to the base of the rete ridges. Varying degrees of differentiation will occur with widely varying levels of keratosis in the superficial layers. Figure 9.4 An example of a basaloid-type vulval intraepithelial neoplasia characterized by pleomorphic cells (1), which extend from the deep epithelial layers to the surface, with a minor covering of hyperkeratotic cells. There is some subdermal hyalinization (2) with abnormal mitoses noted at (3) in the lower levels of the epithelium. Figure 9.5 (a) An example of a Bowenoid-type vulval intraepithelial neoplasia with the cellular atypia characterized by the presence of koilocytes, corps ronds, and frequent mitoses. The differences from the lesion shown in Figure 9.4 are that the superficial layers have a much better developed layer of keratinization (1) and the subdermal layers (2) possess marked lymphocyte infiltration. There are corps ronds present at (3). (b) A high-power view of (a) showing the surface with hyperkeratosis and within the epithelium there are corps ronds with many abnormal mitoses and multiple hyperkeratotic and dyskeratotic cells. Reference has already been made to the second type of intraepithelial neoplasia, namely the differentiated variety. In the early 1960s it was described as carcinoma in situ simplex, but it was later referred to as a well-differentiated variety of intraepithelial neoplasia. Seen in Figure 9.5c, the epithelial cells are mature and deep within the epithelial folds, and abnormal cell keratinization is noted. In Figure 9.5d this keratinization has formed a pearl-like structure (arrowed). It is usually an aggressive lesion with a rapid progression to invasive cancer. Many conditions may mimic the preneoplastic or neoplastic vulval lesions. The flat or papular condylomata and lichen simplex chronicus (previously termed squamous cell hyperplasia) may present problems of differentiation from VIN. Other conditions that may cause confusion are those related to VIN that extends into the pilosebaceous units, tangentially sectioned VIN, seborrheic keratosis, and basal cell carcinoma. Seborrheic keratosis and the basal cell carcinoma of the superficially invasive type both originate from basal cells in otherwise normal epithelium. The cells are uniform with peripheral palisading in the basal cell carcinoma, whereas the seborrheic keratosis contains numerous keratin cysts that are absent from the VIN. Finally, VIN may present with elongated rete ridges that have squamous pearl formations at their tips; these may produce difficulties in determining whether the lesion is entirely intraepithelial, because oblique and transverse sectioning may give the impression that invasion has already begun. Careful orientation of the biopsy specimen is essential, and if in doubt a larger and further sample should be removed for assessment. Diagnosing VIN is not straightforward. VIN does not have a unique clinical presentation; it may present with various symptoms and looks different from one patient to another. In addition, the warm and sometime moist vulval surfaces cause the lesions to become macerated in many cases, making the morphologic recognition of the lesion even more difficult. The main points to bear in mind are: The current ISSVD terminology (2004) describes two types of VIN: usual VIN and differentiated VIN. The division is based on histopathologic characteristics. An additional characteristic is the association with HPV: usual VIN is commonly associated with a high-risk HPV type, whereas differentiated VIN develops in association with a longstanding vulval pruritus, such as that accompanying lichen sclerosus. This terminology affects the clinical presentation as well: As mentioned, VIN may be asymptomatic. Therefore, in every pelvic examination, before insertion of the speculum, one should examine the vulva, perineum, and perianal regions. Unfortunately, most gynecologists bypass the vulva at routine pelvic examination and do not pay attention to this organ, thus missing asymptomatic VIN. Therefore, educating gynecologists to proper vulval examination and recognizing patterns of vulval disease are essential. In addition, the gynecologist should be attentive to some clues of diagnosis in the asymptomatic patient, such as an abnormal Papanicolaou smear or a history of genital warts. These should prompt a careful evaluation of the vulval skin and mucosa, the perineum, and perianal regions, even in the asymptomatic woman. Taking a comprehensive history can also serve to prompt the astute physician to examining the vulva: smoking, past genital STD, previous treatment of intraepithelial or invasive cervical neoplasia, as well as a positive HPV DNA test. VIN does not have a unique clinical pattern, but the main presenting symptom of VIN is vulval pruritus, described in about 60% of patients. However, in 18–40% VIN may be asymptomatic, or associated with pain and burning or with a feeling of a mass or ulceration. VIN can be discovered as an incidental finding during routine gynecologic examination or can be diagnosed during a vulval examination for unrelated symptoms. Differentiated VIN occurs at an older age than the usual VIN type and is often observed in or near areas of lichen sclerosus or lichen planus. Hence, patients with differentiated VIN type often suffer from a long lasting history of itching and burning. We would like to emphasize that, although vulval pruritus is frequent, the clinician should be aware that if therapy for vulval pruritus does not resolve the symptoms and the local findings a biopsy of the persistent refractory lesion should be performed without delay. VIN can have a variety of signs. It may be small and discrete but can involve the whole vulva and beyond. It usually spreads from one or a few centers. Still, in evaluating a lesion suspected for VIN, in order to make the diagnosis, one should categorize each lesion according to the following four clinical characteristics: The toluidine blue test (the Collins test) aims at vital staining of nuclei. It involves staining with a 1–2% aqueous solution of toluidine blue, waiting for a few minutes, and then washing with a solution of 1% acetic acid. The toluidine adheres to the nuclei. In VIN, parakeratosis with abundant nuclei close to the lesion’s surface is a frequent finding; therefore, toluidine blue is expected to localize VIN. A biopsy should be taken from the area where that stain remained after washing. However, this test has become less popular recently, as a result of a high rate of false-positive results: ulcerations, erosions, and inflammatory conditions stain with toluidine blue. Although Joura has reported a sensitivity for detection of VIN of 92% and specificity of 88% with toluidine blue staining, followed by vulval colposcopic examination, he also found that approximately 50% of women with benign squamous cell hyperplasia showed positive toluidine blue staining test. Areas of parakeratosis and suspicious foci of increased nuclear atypia will retain the dye and acquire a deep blue tinge. The normal tissue accepts little or none of the dye. The problem is that hyperkeratotic lesions, although often neoplastic, stain poorly, whereas benign excoriations usually stain in brilliant colors; this gives rise to a high false-positive and also false-negative rate. Figure 9.6 shows such an event, with an ulcerated area in the center of the figure having taken up the dye, giving rise to a false-positive picture. Figure 9.7 shows some of the problems that may be encountered with the application of toluidine blue. In this patient, multiple condyloma acuminata and some areas of VIN were present around the vaginal introitus and fourchette. A 1% aqueous solution of toluidine blue was applied to the vulva with a large cotton swab. Even though the vulva was rinsed with a 1% aqueous solution of acetic acid and the dye wiped off, the resulting denseness of the stain can still be seen and there is no decoloration. This test has given a false-positive result because conditions that involve a rapid turnover of cells (and associated parakeratosis), such as the condyloma acuminata in this case, stain positive with this nuclear dye. The features of the two clinical types of VIN are as follows. Usual VIN is frequently multifocal in the vulva and multicentric in the cervix, vagina, or anus. The most frequently affected sites are the labia majora, the labia minora, and posterior fourchette. Other, less affected sites are the clitoris, mons pubis, and perianal areas. It is important to document the location, because in hair-bearing areas VIN may extend deeply, along the hair shaft and skin adnexae, while in non-hair-bearing regions VIN is usually superficial. The multicentricity of VIN is also age related: decreasing from 60% in women aged 20–34 to 10% in patients over 50 years. The lesion is usually maculopapular, ranging from small papules to sessile plaques. There is an increased surface keratinization, producing a white surface, sometimes with scales. Hypervascularity, if present, may give the lesion a red color. Fissures and erosions are frequent. They may occur spontaneously or as a result of scratching. Usual VIN is a raised, well-demarcated, and asymmetrical lesion, often producing large whitish or erythematous plaques. Usual VIN lesions are pigmented. They may be brown, white, gray, or red. In some cases the VIN lesion presents as a brown papules described by Wade and Ackerman, who named it Bowenoid papulosis, to emphasize the low malignant potential of these lesions and the possibility of regression. These papules may develop during pregnancy and resemble a seborrheic papule. They are sometimes multiple, mainly in the fourchette and inner labia majora. The term “Bowenoid papulosis” is no longer used. It is now also termed multifocal VIN. Since usual VIN is HPV related, it may be diagnosed during a clinical examination in a patient with a positive Papanicolaou or HPV DNA test or in a patient with genital warts. Differentiated VIN is usually a solitary lesion adjacent to lichen sclerosus or squamous cell carcinoma. The most frequent location of a distinct lesion is on the posterior part of the labia minora. The presence of nodularity or an infiltrated area is suspicious for invasion. Sharp margins, hyperkeratosis, elevated, rough and irregular surface, sometimes resembling flat warts. Area of ulceration is suspicious for invasion. Gray, white, or red. Many vulval conditions resemble VIN: condyloma acuminatum, basal cell carcinoma, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, epidermal inclusion cysts, lentigines, Bartholin’s duct cyst, acrochordon, mucous cysts, hemangiomas, seborrheic keratoses, varicosities, and hidradenomas. In addition to these plaques and nodules, pruritic lesions such as lichen sclerosus and Candida infections may also be in the differential diagnosis list. There is a controversy surrounding the role of colposcopy in evaluating the vulva in general, and in cases with VIN in particular. There is a general agreement that colposcopy is essential for studying the cervix in cases of an abnormal Papanicolaou test. Cervical colposcopy concentrates on depicting acetowhite epithelium and abnormal vascular patterns in the transformation zone after the application of 3–5% acetic acid. However, on the vulva, there is no transformation zone, and the vascular patterns associated with intraepithelial neoplasia are less distinct. Furthermore, the opponents of colposcopy of the vulva (vulvoscopy) believe that the whitening seen with acetic acid is common in many healthy women without vulval complaints and therefore may lead to false-positive results, especially when the test is applied by non-experienced clinicians. However, in our opinion, once a lesion has been discovered or suspected, a colposcope is a useful tool to characterize the lesion and outline its margins. The studies quoted as showing a poor correlation between vulval acetowhitening (that is, after the application of a small amount of acetic acid) and underlying pathology were performed in a healthy asymptomatic population, which may have influenced the results. It is, however, important that, if acetic acid is applied, the vulva is carefully inspected beforehand in order to outline pre-existing areas of white skin that are usually due to hyperkeratosis. Following acetic acid application, a systematic examination must be made of the vaginal introitus, labia minora and majora, and perineum. Finally, inspection of the clitoris, terminal urethra, and perianal area and anal canals is undertaken. Consequently, we accept that the colposcope is not advantageous over a simple magnifying glass in screening asymptomatic women for vulval lesions. However, the use of a 5% acetic acid solution to the vulva and colposcopy may clearly demarcate dense epithelial acetowhite areas. On the mucosal surfaces, abnormal vascular patterns, such as mosaicism and punctation, can be depicted. The acetic acid transforms a subtle focus of VIN to a clearly acetowhite epithelium. It is also useful in evaluating the margins of the lesion and planning excisional treatment or vaporization by CO2 laser. Even as a magnifying tool, the colposcope is powerful as it has several magnifications, a good light source, and usually an attached camera or video recorder. The effect of application of acetic acid can be readily seen in Figures 9.8 and 9.9. Figure 9.8 shows the clinical appearance of the vulva; some regions (1) demonstrate circumscribed elevated areas that exhibit a fine punctate pattern produced by enlarged superficial vessels. Area (2) shows hyperkeratosis and a white appearance that is characteristic of superficial hyperkeratosis. In Figure 9.8 acetic acid has been applied and areas (1) now show a white pattern with a fine stippled appearance; this confirms the punctation noted in Figure 9.9. Area (2) remains essentially the same with its typical hyperkeratotic pattern. The areas marked (1) show histologic evidence of VIN. An additional advantage of having the colposcope at the vulval clinic is that examination of a patient with VIN should also include cervix, vagina, and anus, since multicentric disease has been reported in patients with VIN. Up to 50% of women with VIN will have antecedent or concomitant cervical, vaginal, or anal intraepithelial neoplasia. It should also be taken into account that, apart from the colposcope, there are only a few other tests assisting the clinician in diagnosing vulval disease. While for evaluation of the cervix one can use cytologic evaluation, HPV DNA analysis, colposcopy with application of acetic acid, biopsy, and loop excision, for the vulva there is only visualization of the lesion and biopsy. A biopsy can be carried out with local anesthesia. Once the anesthetic has been administered, a sample of tissue is taken in all cases where a suspicion of invasive cancer exists or where the preclinical lesions of VIN have been diagnosed by vulvoscopy or visual inspection. The features suggestive of invasive cancer and which warrant biopsy are as follows: In all these cases, a sample is taken with the intention of obtaining tissue to a depth of at least 5 mm. The tissue to be sampled can be infiltrated beforehand with local anesthetic in the form of 1% xylocaine or lidocaine; this is injected into the subepithelial or subepidermal papillary dermis. EMLA (a lidocaine–prilocaine cream), which is applied to the skin 10–15 minutes before the biopsy is taken, has made the final injection of local anesthetic very acceptable and painless. The insertion of local anesthetic will elevate the skin so that the actual biopsy is made easier. Such biopsies are being taken in Figures 9.10–9.12. In Figure 9.10a, a simple outpatient technique, utilizing local anesthetic infiltration, is being used to obtain a biopsy of a lesion (1). In these circumstances, a fine needle (2) is inserted beneath the lesion to be biopsied and 1–2 ml of local anesthetic is injected after ascertainment that no blood vessel has been entered, thereby elevating the area. EMLA cream has been applied prior to this injection. A small biopsy can then be obtained. Figure 9.10b shows a suspicious hyperkeratotic area (1) that can be biopsied rapidly and relatively painlessly using a sharp biopsy forceps, as shown in Figure 9.11. A Kevorkian or Eppendorfer biopsy forceps (2) (in Figure 9.11) will produce a sample with an adequate depth of 2–5 mm. However, that approach might sometimes fold the tissue so that a tangential microtome cut is made, not allowing the pathologist to give an accurate comment on the nature of the lesion. The 0.5–1 cm defect that is produced can be either left granulating or closed with a single stitch of 3.0 suture material. Silver nitrate or some Monsel’s solution (ferric subsulfate) can be applied. Healing is usually completed in about 2 weeks. After the specimen has been removed, some authors suggest that it be placed “end on”; the dermis side with the serum-wet surface being placed on lens paper or Teflon and the surface epithelium lying face up. To increase the adherence of specimens, some apply a fine layer of lubricant (K-Y Jelly) to the paper towel or Teflon. The adhered specimen and paper towel or Teflon are then placed in either 10% buffered formalin solution or Bouin’s solution fixative. It is most important that the specimen is properly oriented so that tangential sectioning does not lead to difficulty with histologic diagnosis. The Keyes instrument is preferred in taking vulval punch biopsies after EMLA cream has been applied and local anesthesia given. The Keyes punch (Figures 9.12, 9.13) works very much like a cork borer and removes a circumscribed plug of skin, the diameter of which depends on the size of the instrument. In Figures 9.12 and 9.13 a variety of instruments are displayed but the usual one chosen is that which gives a 4–5 cm core of skin ((1) in Figure 9.12); the depth of tissue removed depends on the pressure employed and the sharpness of the instrument. In Figure 9.12, a circular biopsy incision is being carried out. The clinician maintains the pressure and rotation until the subcutaneous tissue is reached. The depth of the biopsy also depends on the epidermal thickness and the factors mentioned above. When the dermis is entered there is a sensation of decreased resistance; if the biopsy penetrates too deep, there will be excessive bleeding. If a shallow biopsy is taken, a fragmented and rather inadequate specimen is obtained. After its removal, the specimen is grasped with some fine-toothed forceps and the dermal tissue is cut, with either a small scalpel or scissors. This leaves a circular or elliptic defect and occasionally some bleeding, which may be stopped using silver nitrate or Monsel’s solution or the insertion of a single 3.0 suture. The specific clinical appearance on the vulva of VIN lesions is highly variable. They were defined in the 2011 International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy (IFCPC) clinical and colposcopic terminology of the vulva (including the anus) review, which covers both normal and abnormal findings (Table 9.2). Approximately 70% of them are multifocal. Their color ranges from white through to black, with shades of red and pink in between. It is estimated that approximately one-third of patients with this disease have hyperpigmented lesions with sharp borders. Lesions may also be dry or moist, and not infrequently they resemble condyloma acuminata, with which they are often associated. They are characteristically papular, being raised above the surrounding skin, and over half exhibit superficial parakeratosis, giving rise to the changes that may be seen with the toluidine blue test and which are described above. Contiguous structures may be superficially involved and, of these, the perineal skin, perianal area, and indeed the anal canal are involved in between 14% and 35% of cases, particularly those in which the posterior part of the vulva is most severely affected. The visual features of the epithelium are affected by the thickness of vulval skin, which in turn affects the opacity of the epithelium. This thickness varies from lesion to lesion and from area to area; for example, the skin of the labia majora hair-bearing keratinized area is thicker than that of the non-hair-bearing labia minora. If a VIN lesion is present, then obviously the thickness and opacity will be increased, and such variations will be accentuated by any associated parakeratosis, acanthosis, or thickening. Associated wart viral infections with their characteristic papillomatosis will, in turn, also affect the colposcopic appearance. Table 9.2 2011 International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy clinical/colposcopic terminology of the vulva (including the anus) Gross neoplasm, ulceration, necrosis, bleeding, exophytic lesion, hyperkeratosis; With or without white, gray, red or brown discoloration Acetowhite epithelium, punctation, atypical vessels, surface irregularities Abnormal anal squamocolumnar junction (note location in regard to dentate line) *See explanatory text. From Bornstein J, Sideri M, Tatti S, et al. 2011 terminology of the vulva of the International Federation for Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy. J Low Genital Tract Dis 2012;16:290–5. As has been mentioned above, the color tone of lesions is variable and many lesions will be colposcopically indistinct until acetic acid is applied; this produces obvious acetowhitening and defines the lesion (Figures 9.8, 9.9). Changes in the angioarchitecture are not as well defined as those seen in comparable lesions on the cervix; however, punctation and mosaic patterns can occur. Punctation can be seen on the inner labia minora in some women with benign conditions such as those presenting with chronic vulval irritation. Although detailed visual inspection aids the determination of the exact location of precancerous lesions, it is impossible without biopsy to predict accurately the degree of VIN change within the epithelium. Changes in skin thickness and coloration are the most accurate visual characteristics associated with VIN. The presence of acetowhite change in the absence of associated skin thickening and changing color tone is recognized to have very little discriminatory value in respect of VIN diagnosis and may, in many cases, be associated with subclinical papillomavirus infections or occur as a result of coital trauma or scratching. In the following sections, the different colored VIN lesions, i.e. white, red, and dark, will be considered individually. White lesions on the vulva are not necessarily precancerous (VIN). However, the following three factors operate in producing this white appearance: When surface keratin becomes moist, it will become opaque and appear either white or gray. The thicker the keratin layer, the more pronounced is this effect. This is one reason why vulvoscopy is not particularly accurate when used to examine vulval lesions, compared with those found on the vagina and cervix. Depigmentation occurs when the basal layer melanocytes are lost or destroyed, or when they are unable to manufacture melanin pigment (vitiligo). Relative avascularity of the tissue occurs when superficial vessels become constricted and when the distance between them and the surface is increased; this occurs in the sclerotic processes of lichen sclerosus. A biopsy must be taken to differentiate VIN lesions from other white lesions that occur on the vulva. In the past these white lesions, including VIN, have traditionally been classified in three major groups, dependent on their histologic morphology. These three lesion groups are: The non-neoplastic epithelial disorders comprise those lesions described as lichen sclerosus, lichen simplex chronicus (formerly squamous cell hyperplasia, hyperplastic dystrophy), and other dermatoses such as psoriasis. Figures 9.14–9.20 show examples of white lesions with associated precancerous change. In Figure 9.14, a combination of condyloma acuminata (1) and thickened white epithelium (2) exists over a large part of the vulva, including labia minora and majora, clitoris, and periurethral areas. A biopsy (Figure 9.15) of the area at (2) shows it to be VIN with a typical uniform neoplastic cell population of the epithelium with hyperkeratosis, and acanthotic rete pegs with numerous mitoses. Figure 9.16 shows the multifocal nature of VIN, again with a thickened and granular surface. The associated pathology (Figure 9.17) shows the very hyperkeratotic layer (1), overlying a neoplastic growth that shows disturbed maturation with pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei, abnormal mitotic figures, and obvious corps ronds (2). The undulating surface of the biopsy corresponds with the clinical picture and could lead to these lesions being confused with those of condyloma acuminata. The value of a biopsy in making a correct diagnosis of these lesions is obvious. In Figures 9.14 and 9.16, involvement of the clitoris and its hood can be seen. With magnified and illuminated vision this involvement can be accurately assessed. Figures 9.18–9.20 show further examples of granular white lesions that give the impression of being of a condylomatous nature, whereas in fact they are VIN. Figure 9.18 shows the outer labia minora of a female whose supposed condylomatous lesion had been treated with podophyllin for a number of years. It was only when a biopsy was taken that the true VIN nature of the lesion was determined. In Figures 9.19 and 9.20 obvious condylomatous lesions (1) (arrowed in Figure 9.19) are seen, but the biopsy revealed the presence of VIN. In Figure 9.20, the clitoris and its hoods are again involved with VIN (as in Figures 9.14, 9.16). The normal redness of the skin is due to reflected light coming from the superficial vasculature through the overlying epidermis. Any increase in this capillary bed will result in an erythematous appearance to the tissue; this appearance will likewise be modified by the thickness of the underlying epithelium, as discussed in Chapter 3. Vasodilation of the underlying vessels may be part of a local immune or inflammatory response to such conditions as candidal infections, allergic responses, seborrheic, dermatitis, folliculitis, and vestibular adenitis. Precancerous red lesions have an increased vascularity and have to be differentiated from other lesions, such as those associated with psoriasis and acute reactive vulvitis. The redness of these lesions is accentuated because of a decreased number of cell layers existing between the surface and the increased vascularity within the dermal papillae. As has been pointed out, in these red lesions there is an evident characteristic histologic pattern with an upward proliferation of the papillae and only a few cells existing between the granular zone and the stratum corneum that intervenes between the surface and the dilated and twisted capillary loops in the papillary apex. This pattern is not only characteristic of red VIN but is also present in psoriasis, where it accounts for the characteristic Auspitz’s sign (the induction of fine capillary bleeding points on the surface of the lesion after it has been scraped with a blunt instrument). Figures 9.21 and 9.22 are low- and high-power views of a mid-vulval red lesion (1) that is raised and resembles red velvet. There are elevated white patches ((2) in Figure 9.22a) and, more peripherally, pigmented areas in the upper labia majora and on the lower left part of the vulva ((2) in Figure 9.21). These variations in clinical pattern were all biopsied to produce a comprehensive record of the status of this patient’s vulva. The red lesion was confirmed as VIN (Figure 9.22b), as were the white and pigmented lesions. Where the lesions are so widespread and extensive, as in this case, some form of excisional technique should be used to ensure that an early invasive cancer is not missed. In the pathology of the VIN lesion shown in Figure 9.22b there is a thin layer of surface parakeratosis, hence the red clinical appearance of this type of intraepithelial neoplasia. The neoplastic cells contain pleomorphic nuclei and there are several abnormal mitotic figures. Many of these red lesions are symptomatic and induce pruritus, pain, and occasional bleeding that results from the fragility of the superficial capillaries. A diffuse erythematous change of the vulva is usually associated with a benign process, but a localized red lesion, such as that seen in Figures 9.21 and 9.22, is suspicious for neoplasia. It must also be differentiated from lesions that result from contact dermatitis as a result of the sensitization of the vulva and perineal skin to a specific agent. It may be necessary to resort to use of the patch test to exclude a varied number of chemical and mineral substances that may be involved in this sensitization. Other causes, such as psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and cutaneous candidiasis, of red vulval lesions must be excluded. In many VIN lesions, intraepithelial melanin, intradermal melanin, or both are present with the result that the lesion may be dark brown or black (Figure 9.23). They have been variously described as a multiple, discoid, flat or gray-brown lesions, hyperpigmented raised lesions, reddish-brown verrucous-type lesions, or papillary lesions. Melanin synthesis in many of these lesions is often increased in the epidermal melanocytes and the excess melanin is then extruded into the underlying papillary dermis, from where it is taken up (phagocytosed) by melanophages. This mechanism is called “melanin incontinence” and results in the pigmented appearance of many VIN lesions. A number of dark lesions of a papillary or spiky condylomatous type have been described in the past as multicentric pigmented Bowen’s disease or as Bowenoid papulosis (Figure 9.24a–d). These lesions are now called simply VIN. They have a discrete papular form, and preserve the histologic features of the previously defined Bowen’s disease of the cutaneous epithelium. In that condition, multinucleation, dyskeratosis, individual cell keratinization, abnormal mitosis, and corps ronds predominate (Figure 9.25). Koilocytotic atypia exists, but, in contrast to that seen in condylomata, the koilocytes are confined to the most superficial layers of the epithelium, are few in number, and their delicate perinuclear halos are replaced by compact concentric clear spaces around the obviously abnormal nuclei. These lesions, however, appear primarily in young individuals and were believed to be clinically innocuous; they were reported to regress spontaneously after sampling. However, some authors suggest that previously defined Bowenoid papulosis cannot be excluded from the spectrum of precancerous vulval lesions. They have also been associated, similar to VIN, with a simultaneously occurring cervical intraepithelial lesion. Figure 9.25 The term Bowenoid papulosis is now rarely used and is regarded as part of the VIN lesion classification. It has been used by a number of clinicians to describe a predominantly multifocal pigmented lesion which runs a benign course, with a proportion undergoing spontaneous remission (60%), and which is found predominantly in young sexually active women. Clinically, as can be seen in Figure 9.24b there are scattered or variously colored lesions covering the perineum, appearing adherent to the skin, with many having a “warty” surface. Sometime they can be smooth and shiny, as seen in Figure 9.24a. In Figure 9.24c, localized areas are seen on both sides of the labia minora in a 19-year-old woman. There is an uncommon presentation with very florid lesions, as seen in Figure 9.24d, in which the whole of the vulva is covered with warty hyperkeratotic lesions varying in color, some areas being white, some red, and others dark brown. These lesions are described as confluent and would seem to occur in immunocompromised patients. They should be investigated intensely as they commonly occur in association with early microinvasive disease. The term Bowen’s disease was used in the past to describe solitary plaques, usually in older women. The lesions are indeed VIN; although essentially pigmented, they may occasionally be white or red and spontaneous remission does not occur. This type of solitary lesion may progress to invasive disease. Such an area is seen in Figure 9.23a,b. Melanomas of the vulva account for 10% of all vulval cancers. The vulva constitutes only 1% of the total skin surface, yet approximately 5% of all melanomas in the female arise in this region. Melanomas may present as a superficial spreading lesion (Figure 9.26a) that occupies an extensive area. They can arise anywhere on the vulva but are most likely to occur in non-hair-bearing areas, especially around the labia minora and clitoris (Figure 9.26b). They may also develop in the area of the urethral meatus and/or vagina and this, in the past, has led to a small number being misclassified. Approximately 10% of them are non-pigmented. An uncommon presentation is as a nodular lesion that is raised with an irregular surface, and this carries an ominous prognosis (Figure 9.27a). The prognosis is directly related to the depth or level of cutaneous invasion (Figure 9.27b), rather than to the size of the lesion. Figure 9.26 (a) A melanoma in situ with the dense black epithelium clearly demarcated. This condition must be excised with a wide margin and a careful assessment of its deeper margins must be made. (b) An early invasive melanoma diagnosed after an extensive biopsy of the pigmented areas. Figure 9.27 (a) A melanoma presenting as a small nodular lesion with an irregular surface and contour at the base of the left labium minus. (b) The pathology shows cutaneous invasion to level 3 (Clark’s classification), which has been determined by measurement from the granular layer of the vulval skin or the outermost epithelial layer of the squamous mucosa to the depth of invasion. Level 3 corresponds to approximately 1–2 mm involvement of the dermis. Experience in the surgical management of cutaneous melanoma has relied on the level of invasion according to the schema by Clark et al. and the measurement of tumor thickness proposed by Breslow. Breslow measured the tumor thickness from the granular layer to the deepest point of invasion and both his and Clark’s measurements seem to be the most reliable predictors of local recurrence and regional lymph node spread. Diagnosis depends on the realization that any pigmented lesion of the vulva could be malignant. As most vulval nevi are junctional, it is recommended that prophylactic removal be employed. However, the features of impending malignancy in a pigmented lesion are those of recent and rapid growth, change in color, bleeding, or pruritus. Biopsy of any such lesion should be excisional, with a margin of normal skin, but if the lesion is extensive a wedge biopsy should be preferred. There is no place for any locally destructive measures in respect of these lesions. The vulva is composed of both hair-bearing and non-hair-bearing skin. This is important to remember when considering the extent of involvement of the pilosebaceous units that are associated with these types of skin; for it is within these units that extensions of VIN may be found. The mons pubis, the lateral and exposed aspects of the labia majora and perianal skin, are covered with hair-bearing skin. The hair follicles, the hair and sebaceous glands, and the apocrine glands form a distinct functional unit throughout these areas of the perianal skin. Also, eccrine sweat glands are found in the labia majora. Non-hair-bearing areas are usually those related to the inner aspects of the labia majora as well as to the whole of the labia minora, the frenulum, and the prepuce of the clitoris. Within these areas there are sebaceous glands that open directly onto skin. However, they are rarely involved with apocrine or eccrine glands. VIN in pilosebaceous units has been extensively studied. When it extends into the underlying dermal hair follicles and/or sebaceous glands, it is in all respects similar to the CIN that obtrudes into endocervical glands. In the vulva, the lesion may be in direct histologic continuity with the underlying pilosebaceous system. In Figure 9.28, a raised pearly white papular lesion extends from the lower border of the labia minora (1) into the inner aspect of the labia majora (2). After the hair has been removed by shaving, the entrance to the hair follicles (arrowed) can be clearly seen within this VIN lesion, which extended in the unit to a depth of about 1.5 mm. Figure 9.29 shows an intraepithelial neoplastic lesion extending into a pilosebaceous unit (arrowed). Figure 9.30 shows the problems that may arise in the diagnosis of VIN in skin appendages. In this figure there are minimal epithelial abnormalities (1) within this squamous cell hyperplastic surface lesion, which has extended deep into the appendages (2) (3) and could be interpreted as VIN.

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

9.1 Introduction

Non-neoplastic epithelial disorders of vulval skin and mucosa

Mixed epithelial disorders may occur. In such cases it is recommended that both conditions be reported. For example: LS with associated lichen simplex chronicus should be reported as LS and lichen simplex chronicus. Lichen simplex chronicus with associated vulval intraepithelial neoplasia should be diagnosed as VIN.

Lichen simplex chronicus is used for those instances in which the hyperplasia is not attributable to another cause. Specific lesions or dermatoses involving the vulva (e.g., psoriasis, lichen planus, Candida infection, condyloma acuminata) may include lichen simplex chronicus but should be diagnosed specifically and excluded from this category.

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)

Non-squamous intraepithelial neoplasia

9.2 Epidemiology and pathogenesis

Prevalence and incidence

Association between vulval intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

Viral etiology

Sexually transmitted diseases as etiologic factors

Human immunodeficiency virus and vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Smoking risk

9.3 Natural history of vulval intraepithelial neoplasia: the rationale for treatment?

9.4 Pathology

Differential diagnosis of histologically confirmed vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

9.5 The clinical examination in general

The effect of the terminology on diagnosis

Early diagnosis

Symptoms

Signs and clinical evaluation

Usual vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Focality

Surface

Thickness

Color

Asymptomatic cases

Differentiated vulval intraepithelial neoplasia

Focality

Thickness

Surface

Color

Differential diagnosis

Vulvoscopy: magnified illumination of the vulva with a colposcope or with direct magnified vision

Biopsy of the vulva

9.6 The clinical examination (specific)

Section

Pattern

Basic definitions

Various structures: Urethra, Skene’s duct openings, clitoris, prepuce, frenulum, pubis, labia majora, labia minora, interlabial sulci, vestibule, vestibular duct openings, Bartholin’s duct openings, hymen, fourchette, perineum, anus, anal squamocolumnar junction (dentate line)

Composition: Squamous epithelium: hairy/non-hairy, mucosa

Normal findings

Micropapillomatosis, sebaceous glands (Fordyce spots), vestibular redness

Abnormal findings

General principles: size in cms, location

Lesion type:

Lesion color:

Secondary morphology:

Miscellaneous findings

Suspicion of malignancy

Abnormal colposcopic/other magnification findings*

White lesions

Red lesions

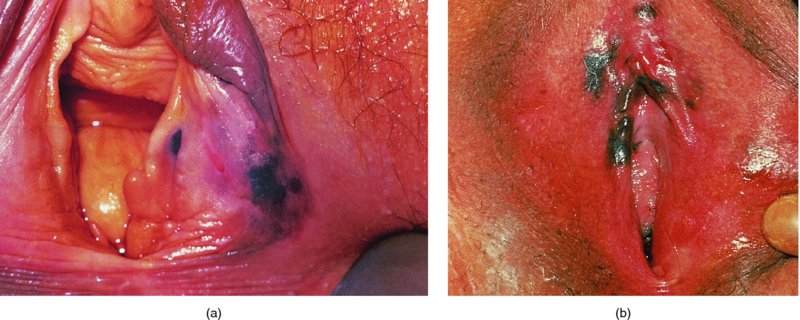

Dark lesions

Figures 9.23–9.25 In Figure 9.23a and b an extensive but localized melanotic area exists on the labia majora; excision biopsy showed it to be vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). Figure 9.24a shows the dark changes which are characteristic of VIN but may, from time to time, be confused with melanotic changes. Such an appearance has also been referred to as Bowenoid papulosis. A wide local excision is necessary, and careful analysis by the pathologist is indicated to differentiate VIN from a more sinister melanotic lesion. The histology of a lesion similar to that shown in Figure 9.24a is presented in Figure 9.25 and shows it to be VIN3 of a type that is also described by some authors as characteristic of Bowenoid papulosis. The pathology of this lesion (Figure 9.25) is highlighted by a uniform configuration of neoplastic cells throughout the acanthotic epithelium with many mitotic figures at all levels of the neoplastic epithelium. In addition to the surface parakeratosis, there are multiple melanophages in the adjacent stroma (right and left) and these are responsible for the pigmented clinical appearance of this type of VIN (also referred to as Bowenoid papulosis).

9.7 Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia affecting the pilosebaceous unit

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree