Venous Cutdown Catheterization

Robert J. Vinci

Introduction

Obtaining vascular access is an integral component of pediatric resuscitation. It allows for the emergency administration of fluids, blood products, and pharmacologic agents required for treatment and stabilization of the acutely ill patient. In 1945, Kirkham first described the technique for saphenous vein cutdown, and through the years other anatomic locations have been demonstrated as possible sites for performing emergency venous cutdown (1,2). Although recent advances such as percutaneous central venous cannulation (see Chapter 19) and intraosseous infusion (see Chapter 21) have diminished the role of venous cutdown, it remains an important option for emergency vascular access in the critically ill or injured pediatric patient (3).

Venous cutdown catheterization is most often indicated for infants and young children, especially in the face of hypovolemia. Clinicians can take advantage of a number of possible anatomic sites, although once the vein is identified, the technique for performing a venous cutdown is similar regardless of which site is used. A venous cutdown is best reserved for the hospital setting because of the time required and the expertise needed to perform the procedure. This procedure is generally performed by emergency physicians, critical care specialists, and surgeons.

Anatomy and Physiology

Venous Anatomy and External Landmarks

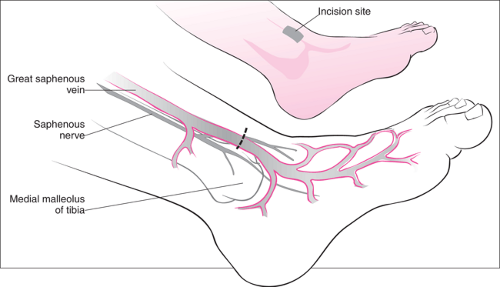

Distal Saphenous Vein at the Ankle

The distal saphenous vein is the most common site for a venous cutdown. Located just anterior and superior to the medial malleolus, the saphenous vein courses adjacent to the periosteum along the medial aspect of the ankle (Fig. 20.1). After the initial skin incision, blunt dissection is usually all that is necessary to locate the saphenous vein (see “Procedure”). The saphenous nerve travels adjacent to the vein and can be confused with the vein, especially when the vein is constricted due to hypovolemia. While the position of the saphenous vein remains constant regardless of age, the diameter of the vessel varies greatly, which has implications for the size of the catheter chosen for vascular access.

Proximal Saphenous Vein at the Groin

In its proximal location, the saphenous vein lies medial to the femoral vein as it courses toward the inguinal region. It passes through the fascia lata of the thigh, where it enters the femoral vein approximately 2 to 3 cm distal to the inguinal ligament. In its proximal location, the saphenous vein can be isolated by using the landmark demarcated by the junction of the thigh with the lateral margin of the labial or scrotal folds (Fig. 20.2). The operator must be careful not to enter the femoral sheath during the procedure so that injury to the adjacent neurovascular structures is avoided. The advantage of the saphenous cutdown at the groin is that the increased diameter of the vessel allows for a larger-bore catheter than does the saphenous vein at the ankle. This is especially useful when rapid infusion of intravenous fluid is required (4,5).

Basilic Vein

The basilic vein is a superficial vessel located just proximal to the flexor crease of the elbow (Fig. 20.3). While the distal portion of the basilic vein originates in the medial aspect of the hand, the vessel diameter is too small in this distal location to be clinically useful for cutdown. However, above the elbow the basilic vein is joined by the median cubital vein and is accessible to dissection and subsequent venotomy. It can be isolated as it courses between the tendons of the biceps and

pronator muscle groups. The median cutaneous nerve of the forearm is often found adjacent to the basilic vein; it should be identified in order to avoid injury to this nerve and potential impairment of sensation over the medial forearm.

pronator muscle groups. The median cutaneous nerve of the forearm is often found adjacent to the basilic vein; it should be identified in order to avoid injury to this nerve and potential impairment of sensation over the medial forearm.

Axillary Vein

Isolation of the axillary vein has been described in newborns as another site for venous cutdown (6). The axillary vein of the proximal arm is situated within the axillary sheath as it traverses the inferior surface of the axilla. To localize the axillary vein, a transverse incision can be performed along the midaxillary line in the deepest skin fold of the axilla. Blunt dissection is then performed to extend the incision to the axillary sheath (Fig. 20.4). The axillary sheath encloses the axillary artery and vein as well as the roots of the brachial plexus. Because of these contiguous major neurovascular structures, a cutdown of the axillary vein is associated with a high complication rate and should only be attempted by experienced clinicians.

Circulatory Physiology

A detailed description of the physiologic effects of the shock state on pediatric patients can be found in Chapter 12. Hypovolemia, tissue hypoxia, and metabolic acidosis are commonly seen in the acutely ill or traumatized pediatric patient. Compensatory mechanisms maintain cardiac output by shunting blood away from nonvital organs, producing counter-regulatory hormones, and buffering lactic acid resulting from cellular anaerobic metabolism. Profound vasoconstriction, particularly when combined with volume depletion (e.g., dehydration, blood loss), can make timely percutaneous vascular access difficult or impossible for the pediatric patient in shock. A properly performed venous cutdown will allow for the rapid volume expansion required to restore vascular tone. It also provides entry into the venous circulation for the pharmacologic treatment of the critically ill child.

Indications

Percutaneous peripheral venous cannulation (see Chapter 73) is normally the procedure of choice when venous access is needed in a pediatric patient. However, acute hypovolemia and acidosis can produce extreme peripheral vasoconstriction, which may make it impossible to cannulate a peripheral vein during a resuscitation. Although an array of vascular procedures (including central venous cannulation and insertion of an intraosseous line) may be initially attempted, performing a venous cutdown remains a viable therapeutic option. This is especially true when other methods are unsuccessful or contraindicated. For example, venous cutdown catheterization is superior to intraosseous infusion with regard to rapid administration of intravenous volume, and a venous cutdown catheterization may prove easier to accomplish than central venous cannulation in certain cases. Consequently, it is imperative to develop clear written guidelines that delineate the protocol and sequence of vascular procedures during a pediatric

resuscitation to ensure that a venous cutdown is properly utilized for the patient requiring emergent vascular access (5).

resuscitation to ensure that a venous cutdown is properly utilized for the patient requiring emergent vascular access (5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree