Vascular Access

Andreas A. Theodorou and Robert A. Berg

Rapid establishment of vascular access is necessary for aggressive fluid resuscitation and administration of medications such as catecholamines, antibiotics, narcotics, and sedatives during emergencies. However, attaining vascular access during a life-threatening illness in a child is difficult and often consumes precious time. An organized approach to vascular access can minimize this potentially life-threatening delay in treatment. This section discusses the priorities in vascular access during emergent, urgent, and stable situations. This chapter reviews various techniques for achieving vascular access and covers the relative indications and potential complications.

PRIORITIES OF VASCULAR ACCESS

Time is critical when attaining vascular access in life-threatening emergencies such as cardiopulmonary arrest or shock. Of course, any preexisting intravenous catheter should be utilized in the initial resuscitation efforts, regardless of how small such a catheter might be. If such access is not available during a life-threatening emergency, intraosseous access should be attained as rapidly as possible, especially in children under 6 years old. A practical approach is to pursue intraosseous and peripheral venous access simultaneously. However, time should not be wasted waiting for attempts at peripheral venous catheterization before attempting intraosseous access, because intraosseous access can be attained more rapidly and more reliably.1 Similarly, skilled clinicians may attempt placing central venous catheters during life-threatening emergencies, but such attempts should not preclude simultaneous attempts at intraosseous access. After attaining intraosseous access for initial fluid resuscitation and infusion of emergency medications, peripheral or central venous catheterization is the next priority in order to ensure a more reliable, long-lasting vascular access.

For urgent situations, such as fluid resuscitation of a child with compensated shock or dehydration, the risk-benefit ratio shifts. Generally, it is most appropriate to initially insert a peripheral venous over-the-needle catheter. If multiple attempts are unsuccessful, or if the child requires fluids or medications that cannot be given safely in a peripheral vein, central venous catheterization should be attempted by a qualified individual. Of course, if the child’s clinical condition deteriorates prior to achieving vascular access, priorities should be reassessed and it may be necessary to attain intraosseous access.

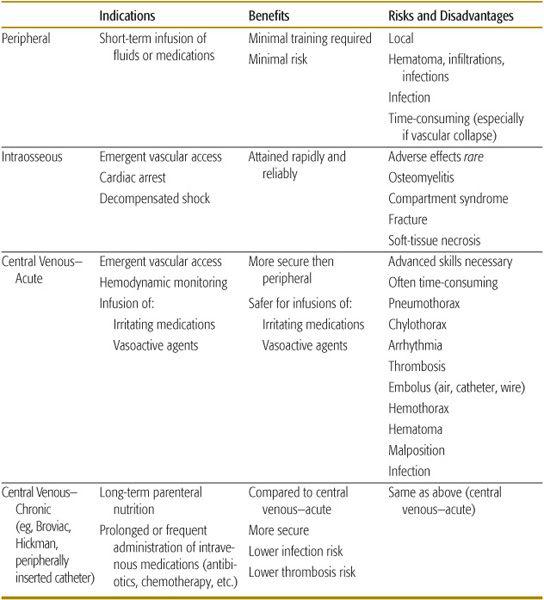

Relatively stable children may need vascular access for maintenance fluids or intravenous medications. Generally, peripheral venous cannulation with an over-the-needle catheter is adequate. If vascular access is necessary for more than 2 to 3 weeks, or if solutions to be infused can cause serious tissue injury if extravasated, a central venous catheter may be necessary. However, central venous catheterization entails added risks, and its inherent risks and benefits deserve consideration (Table 107-1).

Table 107-1. Vascular Access Techniques

PERCUTANEOUS PERIPHERAL VEIN CANNULATION

Small-caliber plastic catheters have allowed for increasingly easy and reliable peripheral venous cannulation. Small over-the-needle catheters (22–24 gauge) are available to cannulate even the small veins of the hand, foot, or scalp of neonates and premature babies. Such peripheral venous catheters are generally all that are necessary for short-term delivery of intravenous fluids or medications.2

The most common complication of peripheral venous cannulation is catheter displacement and infiltration of the tissues with the infusing fluid. Most intravenous solutions are isotonic or hypotonic and easily absorbed from the tissues. Infiltration with these solutions is generally treated by removing the catheter and elevating the limb. However, solutions that are very hypertonic (eg, those containing greater than 12.5% dextrose, 3% sodium chloride, or 8.4% sodium bicarbonate) or that contain irritating substances such as calcium or potassium salts, some antibiotics (eg, erythromycin), or medications with an extreme pH (eg, phenytoin) can cause substantial tissue injury leading to necrosis of the skin or subcutaneous tissues. Importantly, extravasation of vasoconstricting agents such as dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine can result in profound local vasoconstriction and subsequent substantial tissue injury. Even without extravasation of the previously noted medications and fluids, local vascular injury can result in aseptic thrombophlebitis. This condition may serve as a nidus for suppurative thrombophlebitis. The risks of aseptic and suppurative thrombophlebitis increase with the duration of the indwelling catheter.

Selection of catheter size and peripheral venous site are important issues. For a patient in shock, the widest and shortest catheter is optimal, because longer, narrower catheters result in more resistance to flow.

For the trauma victim, it is preferable to insert the catheter into an uninjured limb or at least a limb apparently free from major vascular trauma. The greater saphenous vein, median cubital vein, and external jugular vein are often used, because they are relatively large and consistent in their anatomy. In older children, veins in the back of the hands and forearms are commonly used. Avoiding the dominant hand or the hand with the finger or thumb that the infant prefers to suck allows for improved patient comfort and function, although such choices are not always available.

INTRAOSSEOUS INFUSION

Although emergency intraosseous infusions were common in the 1940s and 1950s, the arrival of butterfly needles and plastic catheters and the widespread use of venisection led to virtual extinction of this technique for several decades. However, there has been a resurgence in the use of intraosseous infusions since the early 1980s.3 Its increasing popularity is primarily because intraosseous infusions can be performed rapidly and reliably. Medical personnel can usually attain intraosseous access in less than 1 minute during emergencies. The bone marrow cavity is effectively a noncollapsible vascular space, even in the setting of shock or cardiac arrest. Therefore, intraosseous access is the initial vascular access site of choice in patients with life-threatening problems such as cardiopulmonary arrest or de-compensated shock.1

Almost any medication that can be administered into a central or peripheral vein can be safely infused into the bone marrow, including crystalloid solutions, colloid solutions, blood products, and hypertonic solutions. In particular, all the medications the American Heart Association recommends for pediatric advanced life support can be safely and effectively administered via the intraosseous route, including catecholamine infusions. Pharmacokinetic variables, such as onset of action and plasma concentrations, are similar with intraosseous or peripheral venous administration in cases of circulatory shock or cardiac arrest with CPR. Emergency medications should be followed by a saline flush to ensure rapid delivery into the circulation. In addition, the initial bone marrow aspirate is a reliable specimen for venous pH and PCO2, blood typing and cross-matching, serum glucose, electrolytes, and blood cultures. Due to stasis in the bone marrow, the results of such studies may be less reliable after administering drugs through the intraosseous needle during CPR.

The greatest obstacle to successful intraosseous cannulation is psychological and originates from the natural reluctance by any inexperienced provider to force a needle into a child’s bone. Experienced providers may at times wrongly forfeit this quick and reliable alternative to undertake venous cannulation via rapid percutaneous central venous catheterization or peripheral vein cutdown, sometimes resulting in dangerous delays in starting therapy. Intraosseous cannulation is generally a safe procedure but can result in complications, including osteomyelitis, fractures, subcutaneous or intramuscular extravasation of toxic medications (eg, epinephrine, calcium), and compartment syndrome. Compartment syndrome is easily avoided by monitoring the insertion site for swelling and discontinuing the infusion if significant swelling occurs. Microvascular pulmonary fat and bone marrow emboli have been demonstrated but do not appear to be a clinically significant problem. The risk of such complications is acceptable in the dire circumstances of decompensated shock or cardiac arrest. Such risks, and the pain involved, may not be acceptable when the clinical indications are less stringent.

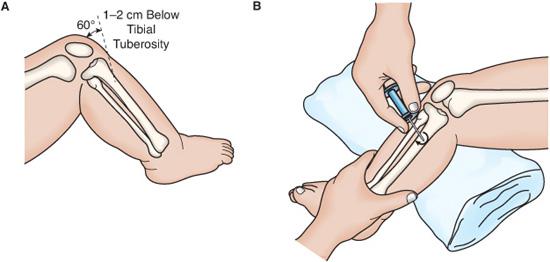

The most commonly utilized site for intraosseous access is the medial surface of the tibia, 1 to 3 cm below the tibial tuberosity. Alternative sites include the distal tibia above the medial malleolus, the distal femur, and the anterior superior iliac spine (Fig. 107-1). There are various styles of intraosseous needles. They are all designed to easily penetrate the bone cortex, and they all have a stylet to keep bone core from obstructing the needle during insertion. Aseptic technique and universal precautions should be followed. The needle should be twisted into, rather than pushed through, the bone marrow. Evidence for successful entrance into the marrow includes (1) the lack of resistance (or a “give”) after the needle passes through the cortex, (2) the ability of the needle to remain upright without support, (3) aspiration of the bone marrow into a syringe, and (4) free flow of the infusion without significant subcutaneous infiltration.1 Aspiration of bone marrow into the intraosseous needle is not always possible, especially in a very dehydrated patient. Infiltration of fluid into tissues around the bone is common when this route of infusion is used for a prolonged period of time or if the fluid is infused under great pressure. Infiltration will manifest as an enlarging leg circumference, fluid leaking out from the skin insertion site, or resistance to flow of the infusate.

CENTRAL VENOUS CATHETERIZATION

Central venous catheterization provides more reliable vascular access than peripheral venous catheterization. In addition, central venous catheters permit hemodynamic monitoring and laboratory sampling of central venous blood. However, the convenience of central venous catheters must be balanced against the added risks.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree