Vascular Access

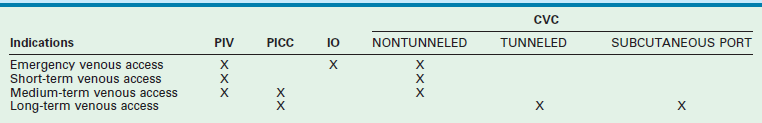

A peripheral intravenous (PIV) cannula is the most commonly used device for venous access in children. Although venous access is often achieved in adults with minimal distress, placement of an intravenous catheter in children can be quite traumatic to the child, the parents, and the attendant health care providers. In some situations, it can be a fairly frustrating and time-consuming procedure.1 Particular circumstances of each child may demand specific solutions for vascular access, namely the choice of device and the site chosen for its placement (Table 8-1). Clinicians must be aware of the limitations and potential adverse effects of the various vascular access devices (VADs) that are available.

In an emergency, other options should promptly be considered after a few failed attempts at PIV cannula placement. Historically, the only available options were a venous cutdown or an emergency central venous catheter (CVC) placement. These options take considerable time and frequently require the services of a pediatric surgeon. Intraosseous (IO) needle placement has become the most common contingency method of emergency vascular access in children. The newer mechanical devices allow easier training of emergency medical personnel and have improved the success rate of IO placement in the prehospital setting. In fact, with appropriate training, an IO needle can be placed more quickly than a PIV cannula.2 In sick neonates, umbilical vessels are frequently cannulated, but can only be used for a finite period [maximum of 5 days for an umbilical artery catheter (UAC)] and 14 days for an umbilical venous catheter (UVC).3 Early placement of a peripherally introduced CVC (PICC) is preferable in these infants. Persistence with using PIV cannulas leads to higher complication rates and reduces the number of future PICC placement sites.

In choosing the appropriate VAD for an oncology patient, the requirements of the oncologist, the patient’s age, expected activity level, expected chance of cure, number of previous VADs placed, and patency of the central veins should all be considered. The number of lumens, size of the catheter, type of catheter, and its location can all be tailored to the specific patient.4 Long-term maintenance of central venous access in patients suffering from intestinal malabsorption is particularly challenging. Once the six conventional sites of central venous access—bilateral internal jugular, subclavian, and femoral veins—are exhausted, one must become more creative in gaining central access.

Complications that are common to all types of VADs are extravasation of infusate, hemorrhage, phlebitis, septicemia, thrombosis, and thromboembolism. Multiple studies have shown that catheter-related blood stream infections can be prevented with appropriate education and training utilizing insertion and maintenance bundles.3,5,6

Peripheral Venous Access

Several techniques have been shown to be beneficial in cannulating a peripheral vein, including warming the extremity, transillumination, and epidermal vasodilators.7 Ultrasound (US) guidance has been used to obtain access to basilic and brachial veins in the emergency department.8 Devices utilizing near-infrared imaging of the veins up to a depth of 10 mm are being used routinely in the hospitals, as well as by emergency medical personnel in the field, to find and access peripheral veins in all age groups.9 Unlike ultrasound, there is no physical contact with the overlying skin and hence there is no compression or distortion of the veins. Significant complications associated with PIV catheters include phlebitis, thrombosis, and extravasation with chemical burn or necrosis of surrounding soft tissue.

Umbilical Vein and Artery Access

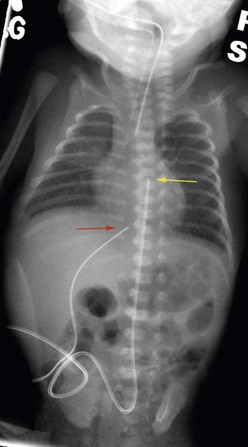

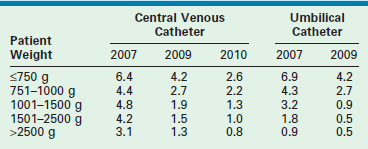

Neonates are often managed with catheters placed either in the umbilical vein and/or one of the umbilical arteries. They can be used for monitoring central venous or arterial pressure, blood sampling, fluid resuscitation, medication administration, and total parenteral nutrition (TPN). To minimize infectious complications, the UVCs are usually removed after a maximum of 14 days.3,10 These catheters are typically placed by neonatal nurse practitioners or neonatologists, and require dissection of the umbilical cord stump within a few hours of birth. It is possible for the pediatric surgeon to cannulate the umbilical vessels after the umbilical stump has undergone early desiccation. A small vertical skin incision is made above or below the umbilical stump to access the umbilical vein or artery, respectively. Once the fascia is incised, the appropriate vessel is identified, isolated, and cannulated. The tip of the UVC should be positioned at the junction of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and the right atrium (RA).11 The xiphisternum is a good landmark for the RA/IVC junction. On the chest radiograph, the tip of the UVC should be at or above the level of the diaphragm. The tip of the UAC is best positioned between the sixth and tenth thoracic vertebrae, cranial to the celiac axis (Fig. 8-1). Various calculations have been proposed to estimate the correct length of the catheter before insertion, based on weight and other biometric measures of the infant.12,13 The long-standing argument about the safety of a ‘high’ versus ‘low’ position for the UAC tip has been laid to rest; the ‘high’ position just described has been shown to be associated with a low incidence of clinically significant aortic thrombosis without any increase in other adverse sequelae.14,15 These umbilical vessel catheters have been associated with various complications. In addition to tip migration, sepsis and thrombosis can occur. UVCs have also been associated with perforation of the IVC, extravasation of infusate into the peritoneal cavity, and portal vein thrombosis.16 UACs are associated with aortic injuries, thromboembolism of aortic branches, aneurysms of the iliac artery and/or the aorta, paraplegia, and gluteal ischemia with possible necrosis.11 Pooled rates of bloodstream infections associated with umbilical catheters and CVCs in level III NICUs has improved over the recent years (Table 8-2).17–19

TABLE 8-2

Pooled Rates of Catheter-Associated Blood Stream Infections Shown as Occurrence Per 1000 Catheter-Days

Peripherally Introduced Central Catheter

PICC lines provide reliable central venous access in neonates and older children without a need for directly accessing the central veins. PICC lines are suitable for infusion of fluids, medications, TPN, and blood products. Many institutions caring for sick children on a routine basis have developed special teams and protocols for placement of PICC lines to reduce variations in practice and increase availability.20 The modified Seldinger technique is used most frequently. A small peripheral intravenous catheter (about 24 gauge) is first placed, preferably with ultrasound guidance, in a suitable extremity vein such as the basilic, cephalic, or long saphenous vein. A fine guide wire is advanced through the vein, the initial catheter is removed, the track is dilated, and a peel-away PICC introducer sheath is advanced over the guide wire. The guide wire is then removed, and the PICC line is introduced through the sheath (Fig. 8-2).21,22 The tip of the PICC should be placed at the superior vena cava (SVC)/RA junction or the IVC/RA junction. Locations peripheral to these are considered non-central and are associated with higher complications.23 PICC lines are also eminently suitable for short- to medium-term (weeks) home intravenous therapy of antibiotics or TPN.24 The most common complications associated with PICC lines are infections, occlusion, and dislodgement of the catheter.25

Central Venous Catheters

With the development of PICC teams and the increasing use of PICC lines, there has been a decline in the use of CVCs in neonates and older children.20 Nontunneled CVCs are used for short- and medium-term indications, whereas surgically placed tunneled CVCs are used for medium- and long-term indications. In premature neonates, if PICC placement is not successful, tunneled CVCs are preferentially used because of their smaller size and durability as opposed to nontunneled CVCs. The central veins accessed for placement of CVCs are the bilateral internal jugular veins, subclavian veins, and femoral veins. In older children and full-term neonates, the percutaneous Seldinger technique is used. In premature neonates and occasionally in older children, the relevant central vein or one of its tributaries (i.e., common facial vein or external jugular vein in the neck, cephalic vein in the deltopectoral groove, or the long saphenous vein at the groin [Fig. 8-3]), is dissected and cannulated.26–28 In some emergency situations, percutaneous femoral vein access may be preferred as the insertion site is away from the activity centered around the head, neck, and chest. The tip of a CVC placed from the lower body should be positioned at the junction of the IVC and RA, which will ensure prompt dilution of the infusate and likely has a lower chance of thrombosis. Again, the xiphoid process is a good surface landmark to estimate the length of catheter needed. Radiographically, the tip should be positioned just above the diaphragm.

FIGURE 8-3 This broviac catheter was placed through a cutdown at the groin to access the long saphenous vein close to the saphenofemoral junction. The catheter is positioned in a subcutaneous tunnel in the thigh to exit just above the knee on the anteromedial aspect.

A CVC placed through an upper body vein should be positioned such that the tip is at the junction of the SVC and RA. Surface landmarks for this location are less reliable. A point about 1 cm caudal to the manubriosternal junction, at the right sternal border, gives a close estimate to the SVC/RA junction in toddlers and older children. The lower margin of the third right costosternal junction has been shown to be the best surface landmark in adults for placement of the CVC tip at the SVC/RA junction.29

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree